Earlier this week I published the findings of my latest focus groups to explore how voters around the country saw things seven eventful months on from the general election. My new poll underlines that despite what has felt like the frenetic pace of politics for those who follow its twists and turns, surprisingly little has changed. There is little in the numbers to comfort either party.

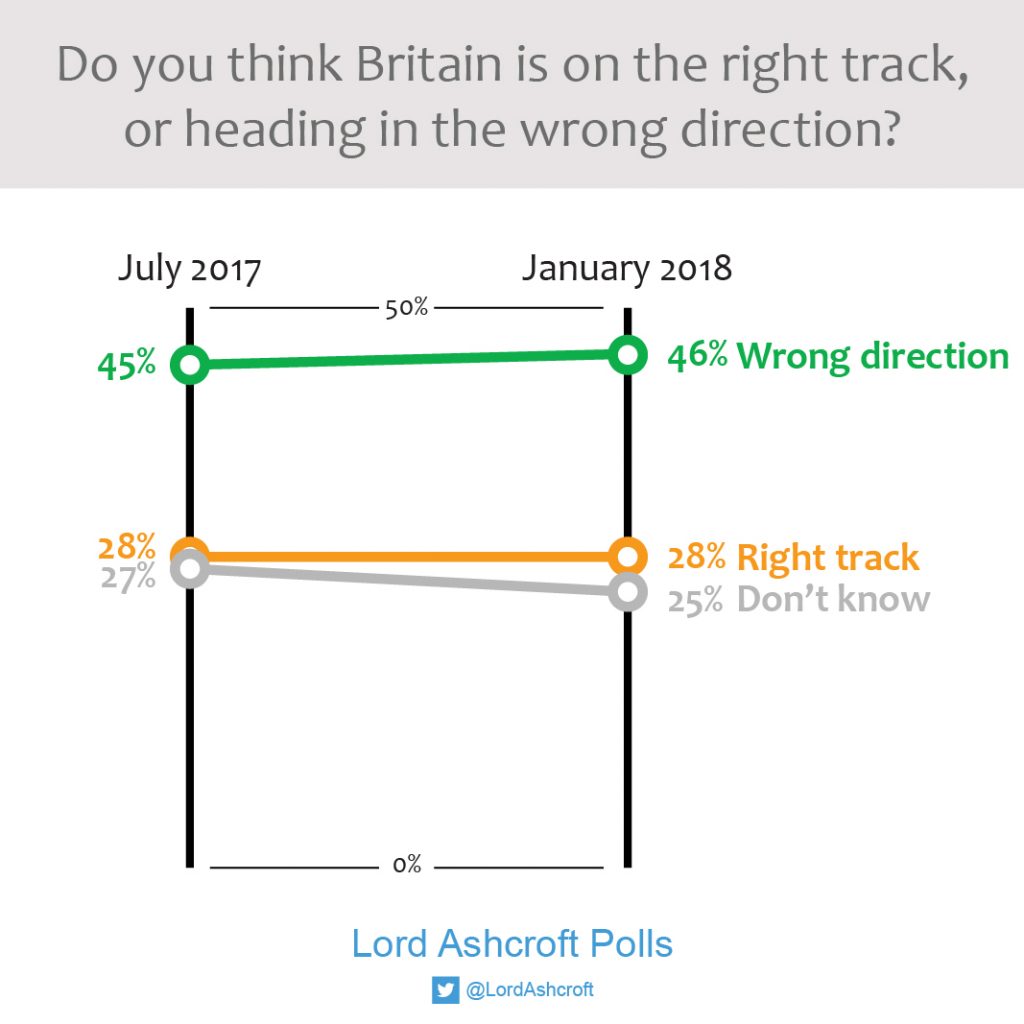

In my post-election research for The Lost Majority I found only 28 per cent saying they thought the country was on the right track. This week that number is unchanged, with nearly half – including seven in ten of those who voted to remain in the EU – saying things are heading in the wrong direction.

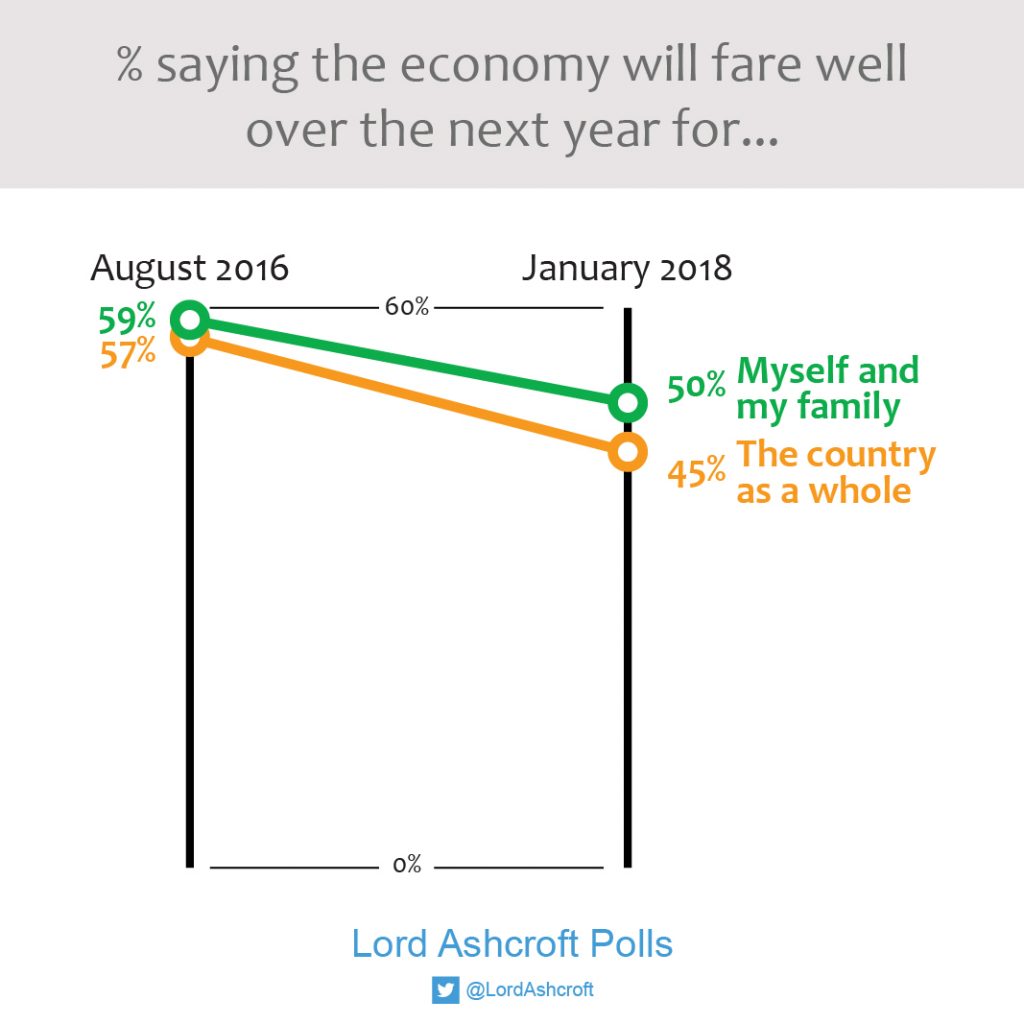

I also found people less optimistic about the future of the economy than they were last time I asked, shortly after the referendum. Voters overall were more likely to think things would go badly over the next year for the country as a whole than to think they would go well, and they were evenly divided over the prospects for themselves and their families. Perhaps not surprisingly, Leave voters were much more optimistic than remainers. Interestingly, though, those who had voted remain were considerably more likely to think the economy would fare badly for the country than for them personally: three quarters thought things would go downhill for Britain as a whole, but only just over six in ten for themselves and their families. Nearly three quarters of Conservatives, incidentally, thought things would go well both personally and nationally.

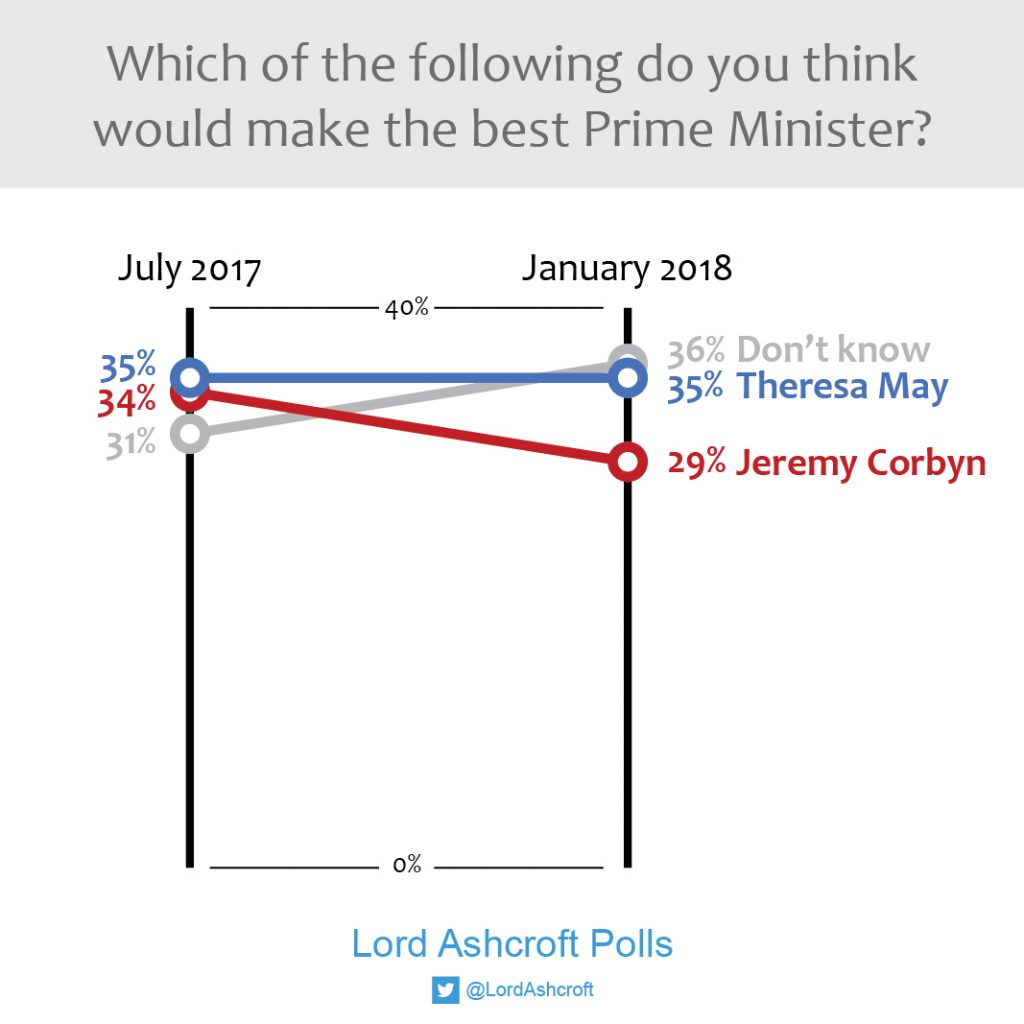

Despite this generally gloomy outlook, the proportion preferring Theresa May to Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister was also unchanged since July, at 35 per cent. Indeed over the same period the number saying they preferred Mr. Corbyn actually fell by five points to 29 per cent, with the balance shifting to ‘Don’t Know’ – now the most popular answer. It is striking that while 78 per cent of Conservatives preferred Mrs. May, fewer than two thirds of those who had voted Labour named their own leader. While Remain voters preferred Mr. Corbyn over Mrs. May by nearly two to one, still fewer than half (44 per cent) said they would rather see the Opposition leader in Number Ten.

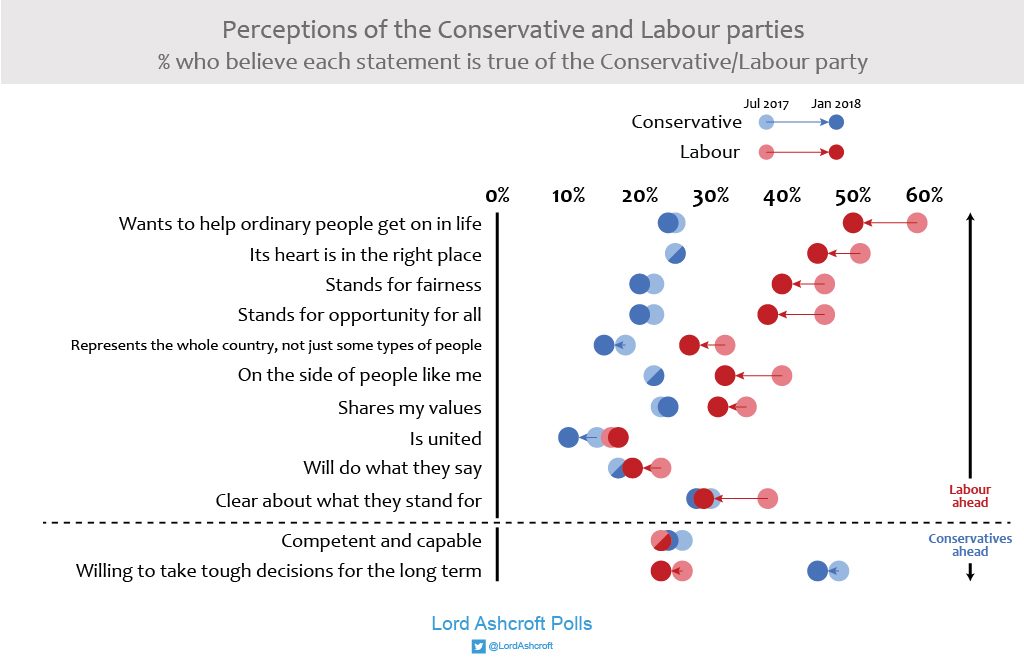

One of the most important findings in my post-election research was the erosion of the reputation for competence that has been central to the Tories’ ability to win elections. I argued that regaining this reputation was the party’s most pressing task, but no such recovery is yet underway – only a quarter said they considered the Conservatives “competent and capable”, a measure on which they remain all but neck and neck with Labour.

As in the summer, the Tories lead comfortably on only one attribute – being “willing to take tough decisions for the long term” – but it is notable that both parties have retreated on practically every measure, and Labour more so than the Conservatives. Two factors probably account for this: the limited limelight available to Opposition parties outside an election campaign, and the fact that on many of these qualities the Tories didn’t have a great deal further to fall.

Brexit and a second referendum

A few weeks ago, on Twitter, I conducted the first part of an experiment. I posted a survey asking whether people wanted a second referendum on Brexit, and urged them to retweet it so others could take part. More than 180,000 people voted, of whom 67 per cent said they were in favour of a second referendum, with 28 per cent against. Only 5 per cent said they didn’t know. The result delighted many vocal Twitter remainers, especially those who adorn their profiles with the hashtag #FBPE (“Follow Back Pro-EU”), who were particularly assiduous in sharing the survey to encourage like-minded people to vote. I said at the time that I intended to compare the result of this completely unscientific Twitter “poll” with a real poll, conducted and weighted to ensure the data represents the population of the country, not just those who happened to see my tweet. Remain campaigners will be rather less pleased with this second part of my experiment.

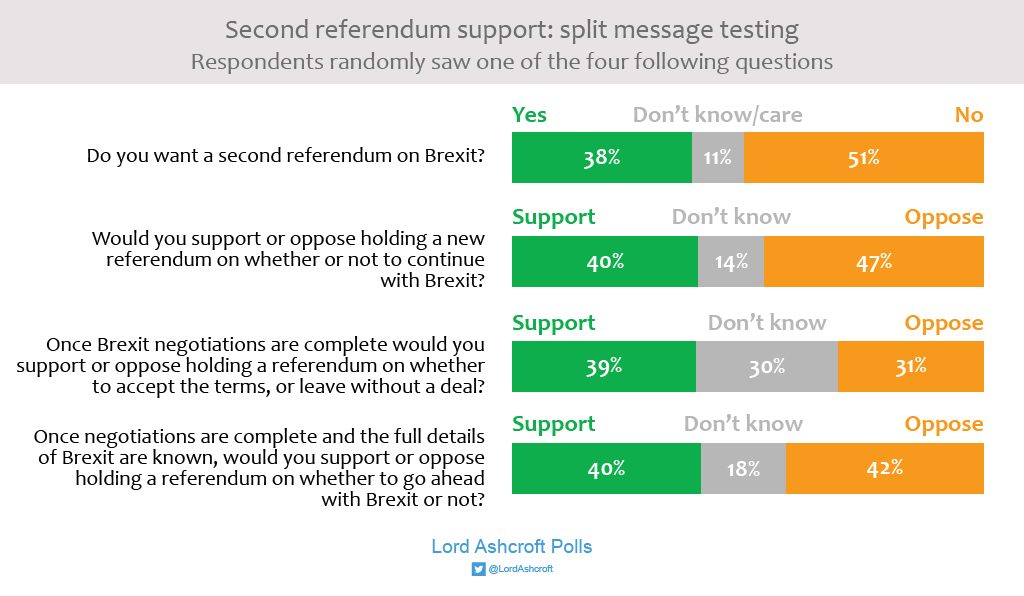

Since it is not always clear what people mean by a second referendum, I split the sample four ways and gave each a slightly different version of the question, to see whether the different circumstances would make any difference. A quarter were simply asked whether they want “a second referendum on Brexit,” as I did on Twitter. Another quarter were asked if they wanted “a new referendum on whether or not to continue with Brexit”. The third group were asked whether, once negotiations were complete, they wanted “a referendum on whether to accept the terms, or leave without a deal”. The final group were asked whether, at the end of negotiations, they wanted “a referendum on whether to go ahead with Brexit or not”.

There was no significant variation in support for a new referendum in any of the scenarios: between 38 and 40 per cent depending on the question. Opposition to a new referendum outweighed support (indeed with between a quarter and a fifth of remainers answering in the negative) in all scenarios but one: a choice between accepting the terms negotiated for Brexit, or leaving without a deal – that is, a referendum which would result in Britain leaving the EU in any event. This was both the least unpalatable option to leavers, a quarter of whom supported the idea, and the least attractive to remainers, only 57 per cent of whom were in favour.

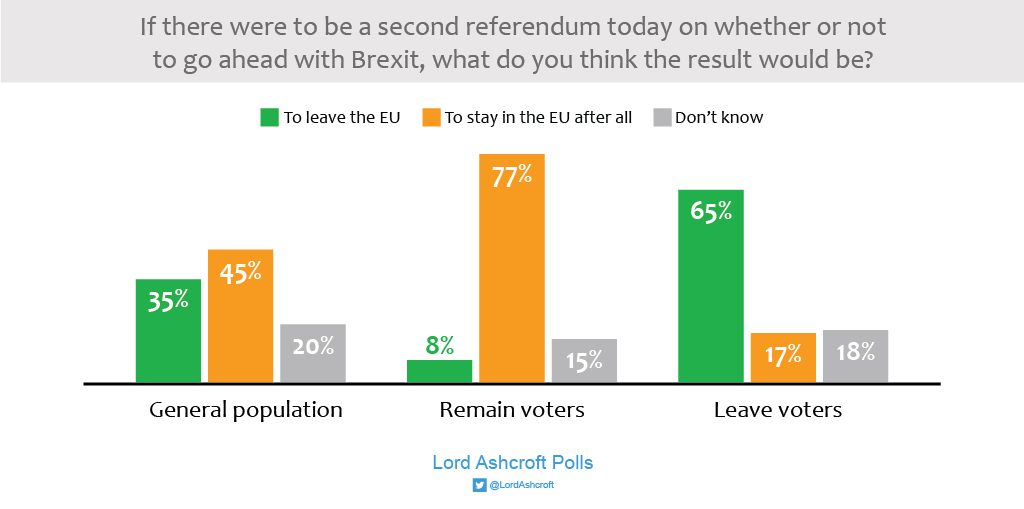

However, if there were to be a referendum today on whether or not to continue with Brexit, more people said they thought the answer would be to stay in the EU after all than thought the verdict would be to go ahead and leave.

As so often, the split between Remain and Leave voters was telling. Each side thought theirs would win such a referendum – but remainers were more certain than leavers that most people now agreed with them.