This is a text of a talk I gave last week to the International Democrat Union, the global alliance of the centre right, looking at the challenges the conservative movement will face whatever the result of the current round of UK and US elections.

The title of this session is ‘Conservatives at a Crossroads – where do we go from here?’ This is always an excellent question, but when deciding where to go and how to get there you first need to know where you are.

At first glance, we seem to be in a good position. In the US, the Republicans control the White House, the Senate, and most state legislatures. In the UK, the Conservatives have been in government for nine and a half years and, according to the bookies and most pollsters, look set to get a new mandate with an overall majority.

But when we look in detail at the research – both on current elections and over the longer term – we can see hazards that the conservative movement is going to have to navigate on both sides of the Atlantic, and which will apply in different ways in all the countries represented in this room. Let’s start with the election in the UK.

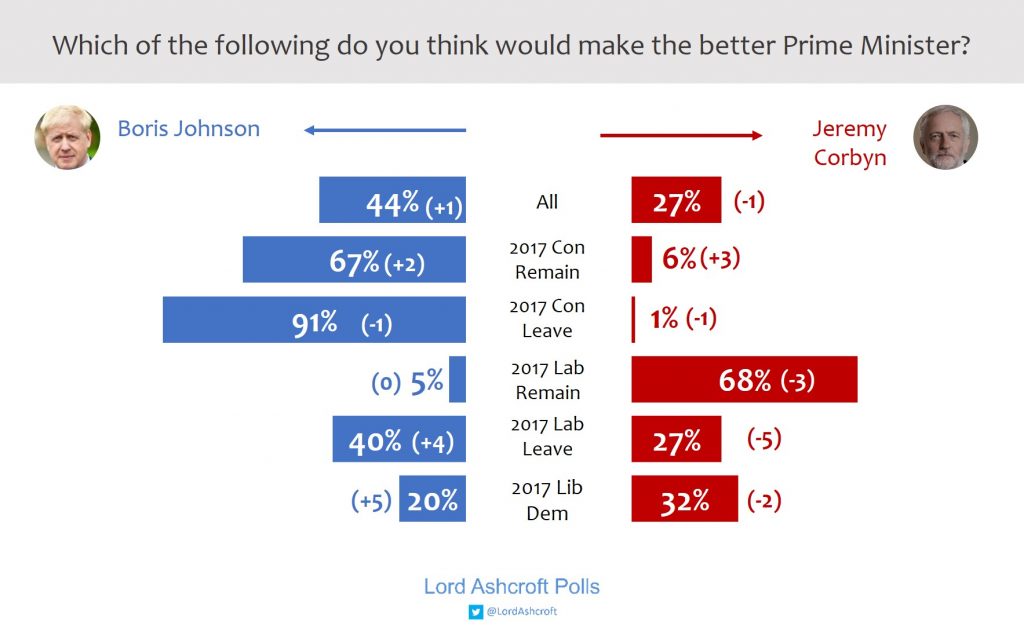

In common with other polls, my surveys find Boris Johnson maintains a comfortable lead over Jeremy Corbyn as the best available Prime Minister. Only a quarter of voters think Corbyn would do a better job. The Conservative team is also more trusted to run the economy, and when we force people to choose between a Conservative government led by Boris Johnson or a Labour government with Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister, at this stage we still find a clear – if not overwhelming – preference for the former.

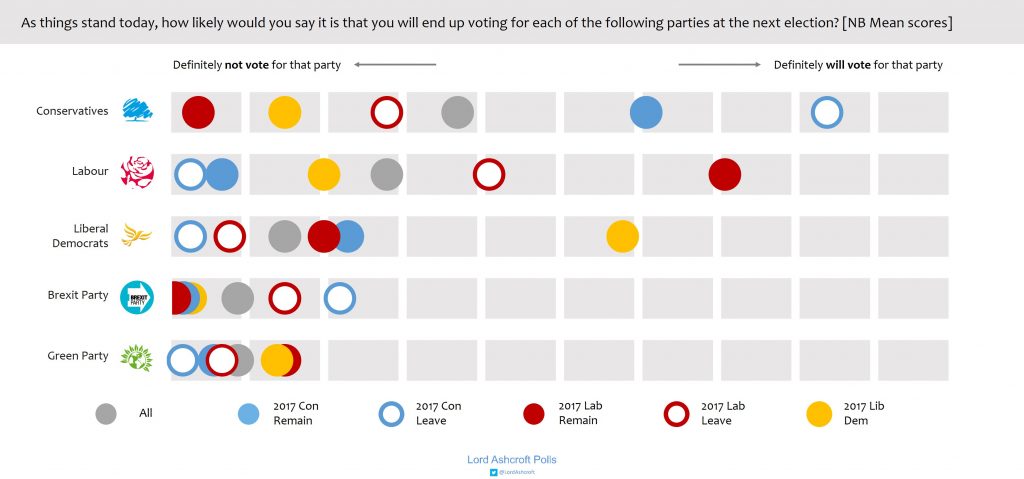

And when we ask how likely they feel they are to vote for each party on a 100-point scale, we see Conservatives retaining much firmer support from their 2017 voters than Labour or the Liberal Democrats. While Conservative Remain voters are less sure about their vote than Tory leavers, as a whole they are still more inclined to stick with the party than abandon it – partly because they think the referendum result should be honoured, and partly because they think Brexit will be a walk in the park compared to having Jeremy Corbyn in Downing Street.

The fundamentals, then, are clearly in Boris Johnson’s favour. But recent polls have found the Labour vote firming up, and even with a week to go it feels as though this election is somehow not settled yet, with many uncertain voters still to make up their minds.

But even if we do get the Conservative majority most analysts expect, we should not take this is a wholesale endorsement of the Conservative Party, or of conservatism itself. We need to take a much longer view. As in other countries, the political situation we have in Britain today is the result of a long series of disruptive influences: the Iraq war, the expansion of immigration from the EU, the scandal over MPs’ expenses, the financial crisis and the years of austerity that followed it, the Brexit referendum and parliament’s inability or unwillingness to implement the result have all been steps on the path to this point.

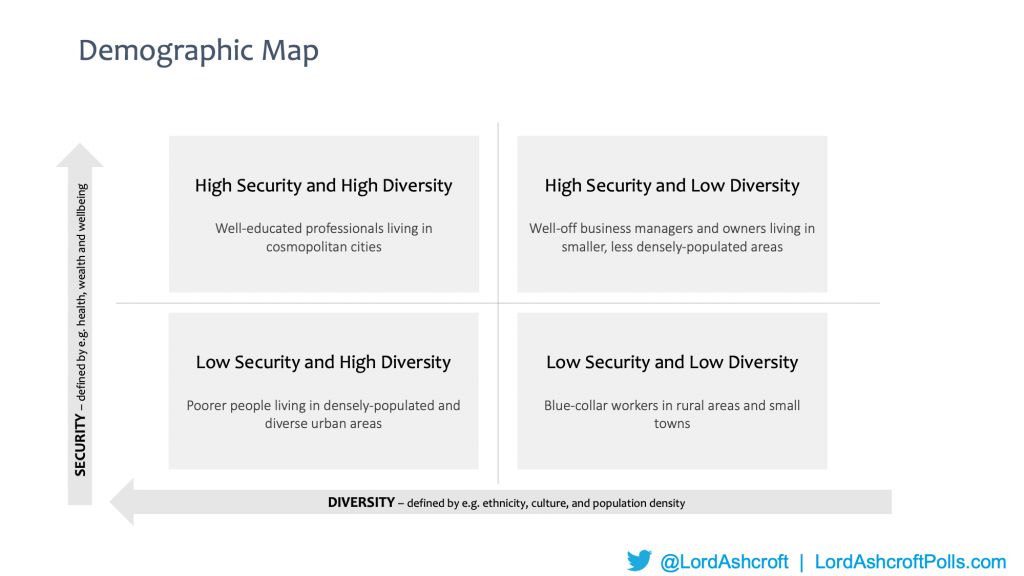

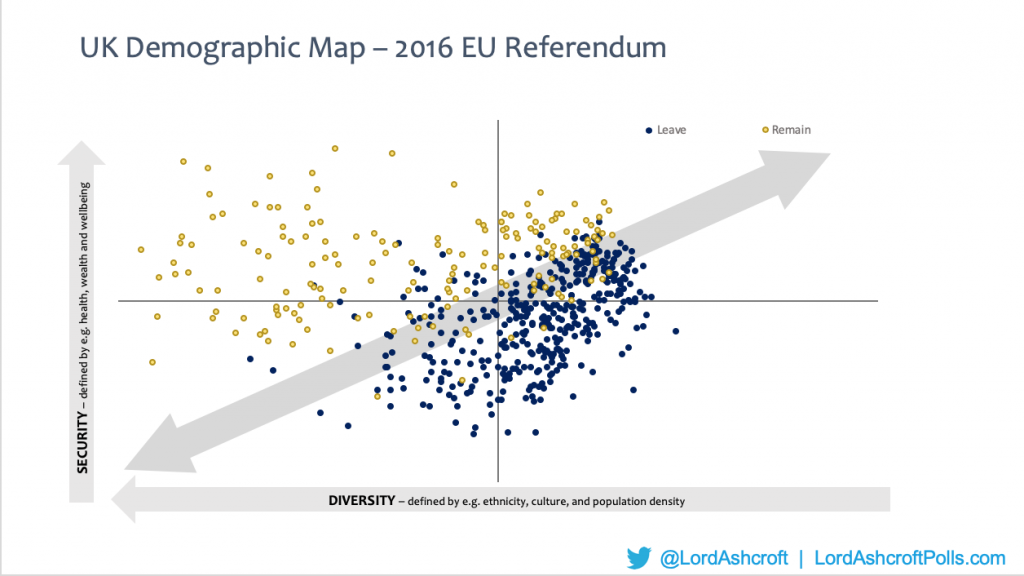

A good way of exploring the effect of these developments is to chart them on a geo-demographic map like this one.

The vertical axis represents security, which includes measures of wealth and wellbeing such as income, house value, occupation, education and health or disability. The horizontal axis represents diversity – a combination of factors including ethnicity, population density, urbanity and housing tenure. All these measures are derived from census data. By combining this information with election results and poll findings, we can study how opinion and voting behaviour varies – sometimes in unexpected ways – between people depending on their life situation and location.

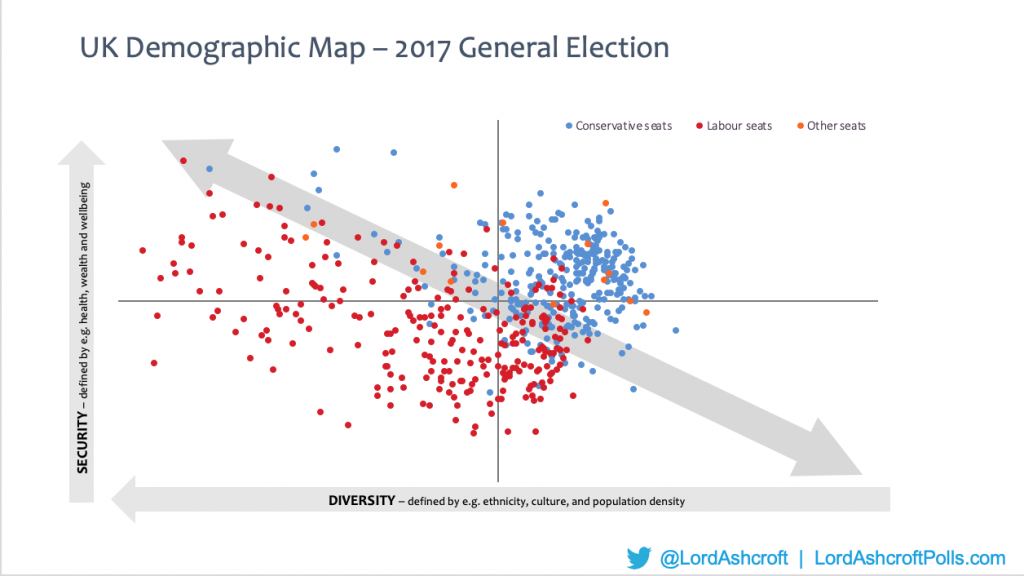

Here we see the constituencies won by the Conservative, Labour and other parties at the 2017 general election plotted on such a demographic map. Conservative seats dominate the less diverse but more prosperous top-right quadrant, with Labour holding all but a handful of seats in more diverse, less well-off territory.

But when we look at how those same constituencies voted in the EU referendum, we see the country divided along completely different lines. In demographic terms, Leave support was centred in the poorer and less diverse parts of the country, with support for Remain heavily concentrated in richer, more urban centres and university towns. In terms of attitudes, the divide over Brexit was much more along cultural lines than along traditional left-right ones.

In 2017, Theresa May called an early general election in the hope of reassembling the Brexit-voting coalition under the Tory banner. In fact, she got the worst of both worlds.

Many Remain voters deserted the Conservatives because of Brexit. But most of the Leave-voting former Labour voters who were supposed to take their place refused to fall into line with what they saw as the party of cuts. This explains why – so far! – no party has since been able to assemble a majority electoral coalition.

One important feature of the last election was that the Conservative voting coalition was older, whiter, more working class, more socially and culturally conservative and with fewer graduates than it had been before. This was also seen in the distribution of seats, with the Tories losing places like Kensington and Canterbury but making gains in former industrial Labour heartlands like Mansfield and Stoke. We can expect to see that process continuing this time round.

This is obviously a double-edged sword for the Conservatives. For many years, the party used to have long, solemn debates about how to attract more working-class voters, and the fact that the Conservatives are competing and winning in seats where they have never done so before is, in that sense, a real achievement. At the same time, though, a Conservative Party that ceased to be the natural home of affluent suburban professionals would have a lot of hard thinking to do. Like a business, a party should beware of taking a bigger share of a shrinking market.

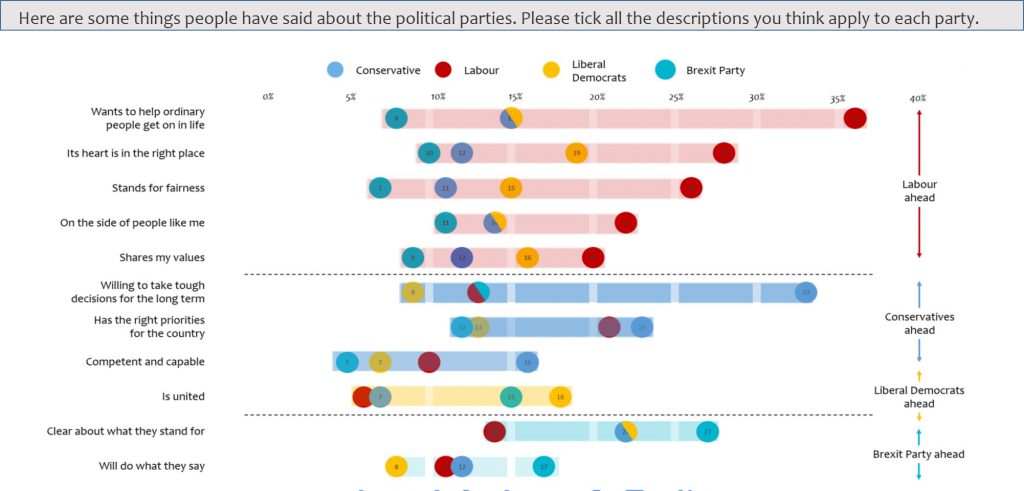

I think there are two more hazards for the Conservatives, even if they emerge victorious a week today. One would be to conclude that the Conservative Party is regarded with any kind of fondness. We get a flavour of that from a question I asked earlier in the campaign about what attributes people associate with each party.

Of the main parties, the Conservatives are seen as the most willing to take tough decisions for the long term – with around one third of voters saying this is true of the party. They also lead – just – on having the right priorities for the country. Only 16% – one-six per cent – say the Conservative Party is “competent and capable”. The fact that this is enough to put it ahead of both Labour and the Liberal Democrats tells you a good deal about how the voters see our political class at the moment. Meanwhile, for all their faults, Labour are considered by far the more likely to want to help ordinary people get on in life, to stand for fairness and to have their heart in the right place.

This makes it much harder than it would otherwise be for lifelong Labour voters to switch to the Conservatives. In our focus groups, we see people genuinely agonizing over whether they can bring themselves to vote Tory, even though they want to get Brexit done and think Jeremy Corbyn would be a terrible Prime Minister.

All this means that of those Labour voters who do decide to switch to the Conservatives, many will do so simply to get Brexit done, intending to switch back as soon as it’s out of the way and Labour once again has a half-way acceptable leader. It would never have crossed their minds to vote Tory otherwise. In other words, we will probably see a temporary and transactional swing to the Conservatives, rather than a conversion to conservatism.

So, having cast a pre-emptive shroud over the Conservative Party’s celebrations, let me turn briefly to the US.

Like the Conservatives in Britain, President Trump and the Republicans have been lucky in their opponents. My polling since 2016 has consistently found around one in three Trump voters saying they were voting mainly to stop Hillary Clinton, rather than positively endorsing The Donald. And in my most round of research to mark a year until the election I found little enthusiasm for most of his potential challengers, even among likely Democrat primary voters. Joe Biden seemed to lack new ideas and have too many “senior moments.” People worried about the health of Bernie Sanders and few warmed to Elizabeth Warren, and even Democrats worried about the cost of their healthcare and college plans. Many thought Pete Buttigieg was smart, constructive, and likeable, though some worried about his relative youth and inexperience.

Meanwhile, most of those who voted for Donald Trump say he has met or exceeded their expectations. They point to a thriving economy, conservative appointments to the Supreme Court, a firm stance on immigration and border control and what they see as his determination to stand up for America in the world.

But there are Republicans voters in play. These are most likely to be found among those who previously voted for Barack Obama; those who were voting mainly to stop Hillary; and the moderate suburban voters who switched sides or stayed at home in last year’s midterms to give Democrats control of Congress. Many of these voters are weary of his antics, and some worry about what a second term would bring. They are open to an alternative.

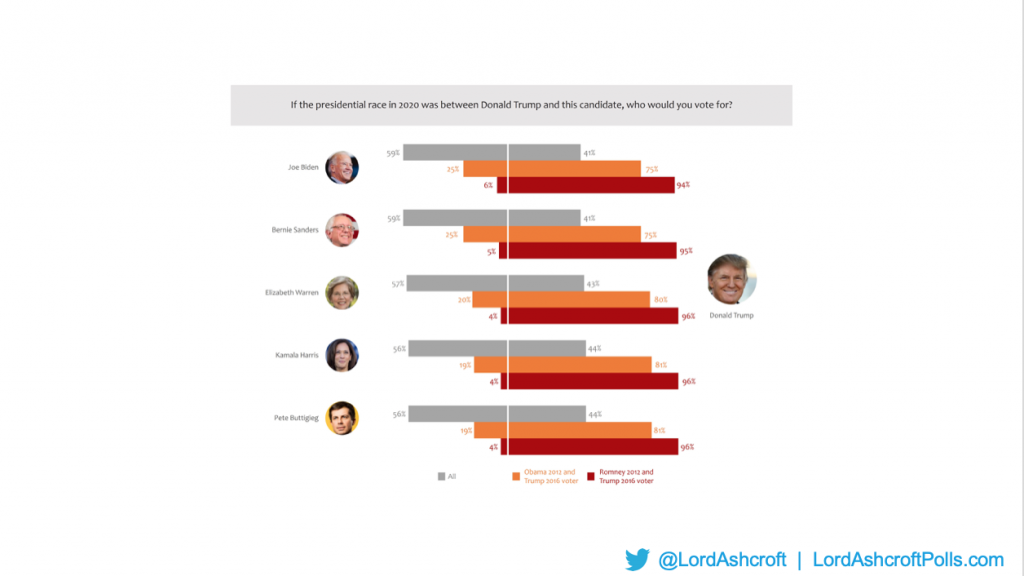

At this stage, many national polls suggest that any one of the Democrat frontrunners could beat President Trump next November. And these figures from my October poll show around one in five Obama-Trump voters saying they might vote for Warren or Mayor Pete in a head-to-head with Trump, and one in four saying they could back Biden or Sanders.

But at this stage, such findings should be taken with a wheelbarrow of salt. Most voters have other things to think about and will not properly tune into the process at least until they have a firm nominee to compare against the President. But speaking to undecided former Trump voters last month, we found that the main message that drifts across from the Democrat camp is “free this, free that.” While healthcare is one of their biggest concerns, they worry about the tax implications of Medicare for all and free college. Suburbanites may yet decide they like their hard-earned dollars more than they dislike Donald Trump’s Twitter feed.

Many of them also feel that the Democrats still regard them as a “basket of deplorables” for having had the temerity to vote for Trump in the first place. This still rankles, and makes it harder for the party to recruit them. And while they still broadly see President Trump as a change in the right direction, the current most likely alternatives sound to many like either a change back to how things were, in the case of Biden, or a change in a wrong and potentially threatening direction, in the case of Warren and Sanders.

Meanwhile, we have the diverting spectacle of the impeachment hearings, which Democrats see as the final demonstration of Trump’s unsuitability to be President, but Republicans more often see as the culmination of a three-year witch hunt.

All of which means, in my view, that the 2020 election is still very much in the balance. But as in the UK, even if Trump carries the day next November, there are broader questions that should give American conservatives pause for thought. One of these is how support for the two parties has shifted in recent decades.

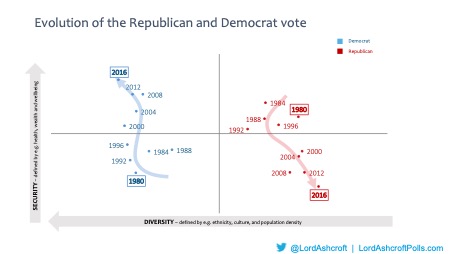

This is how the Republican and Democrat vote has evolved over the last ten presidential cycles, from 1980 to 2016. It’s not a straight line, but the trend is very clear. In the Reagan era, Republican support was centred squarely in the top right quadrant of the map, among ‘high security, low diversity’ voters. Over time, this has drifted down to the bottom right, as the GOP’s centre of gravity has shifted to less prosperous rural and small-town America. On the other side, the opposite has happened. While always being rooted in more diverse populations, in economic terms the Democratic vote has grown steadily more upscale.

This is a more extreme version of the point I made about the way the Conservative voting coalition has changed in the UK. It has become a cliché to talk about the polarization of American politics, but the problem is that for some time, rather than trying to ameliorate those divisions, politics has emphasized and supercharged them. People often blame Donald Trump for this. But the truth is that, like Brexit in the UK, he is the latest in a long line of divisive political developments going back at least to the Clinton era. The 1994 Republican Revolution, the Clinton impeachment, the hanging chads of the Bush-Gore election, Iraq, the financial crisis, Obamacare and the rise of the Tea Party have all combined with the rise of talk radio, cable news social media to create the political atmosphere we have today.

That divided atmosphere always presents the temptation to behave in a way that makes the problem worse. Politics becomes ever more poisonous, and ever more removed from the practical problems that confront people in their daily lives, and the anxieties they have about their family’s future. You can win by emphasising these divides – but only for a time, and only at the cost of undermining support for the values and institutions which conservatives should be looking to preserve.

To conclude, I think all this evidence points to three broad conclusions for parties of the centre-right.

The first is that brand still matters, and perhaps more than it ever did. It is not always enough to be on the right side of an issue if voters mistrust your motivation and ability to deliver on their behalf. We won’t always be as lucky as Boris Johnson and Donald Trump in the opponents we face.

The second is that we must never assume the important arguments on things like capitalism, free trade and the market economy have been won, once and for all. Anyone who has reads the British Labour manifesto – and who sees the popularity of some of its policies on things like state ownership – will quickly see that this is not the case at all. And we should bear in mind that many in our own voting coalitions are not enthusiasts for globalisation, but are looking for more economic security.

The third is that we must not be trapped by the division and polarisation of politics and confine ourselves to our own corner of the demographic map. The most successful politicians in our era have been the ones to build the biggest and most enduring coalitions of voters. Not to identify divisions and exploit them, but to put their principles to work for the benefit of people in all parts of society. And if that sounds a bit soft and fluffy, let me say that the two leaders I have in mind are Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – people of undoubted conservative conviction who kept pace with social and cultural change without alienating their core supporters, and who showed people who had never before voted for their parties that there was something in it for them.