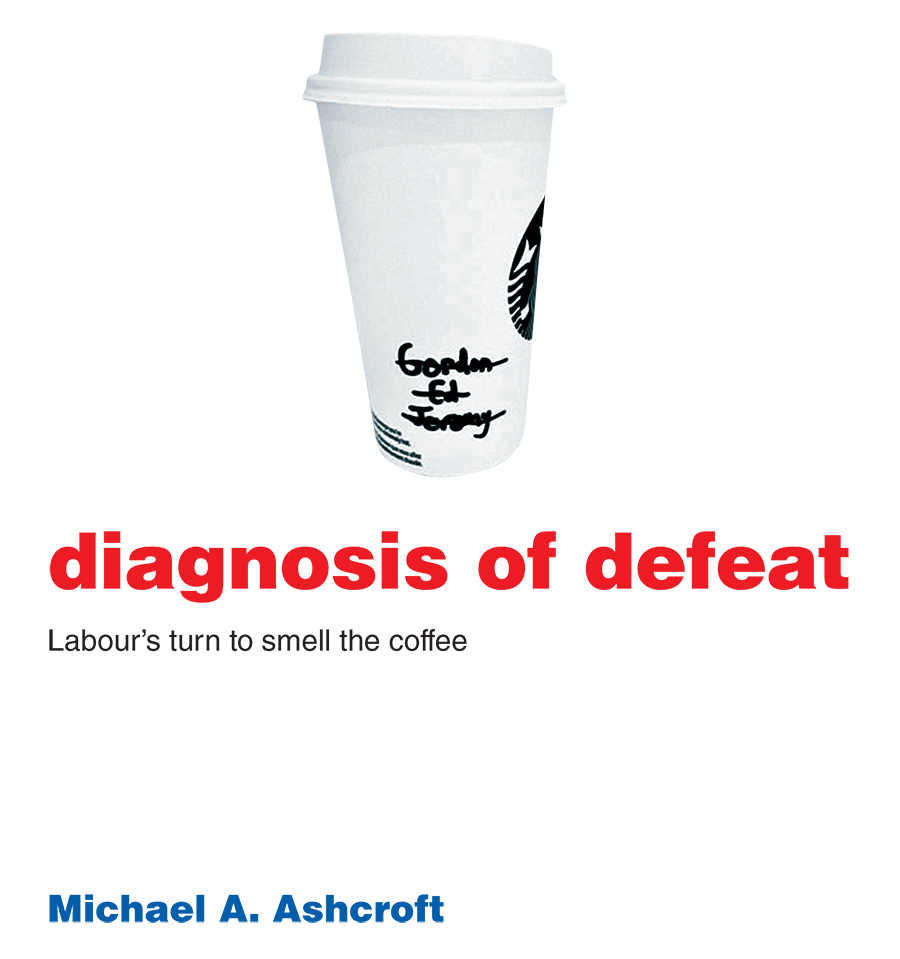

After the Conservatives lost their third consecutive election in 2005, I published Smell the Coffee: A Wake-Up Call for the Conservative Party. I felt that the Tories had failed to grasp the reasons for their unpopularity and needed a serious reality check if they were ever to find their way back into government. With Labour now having been rejected by the voters four times in a row, I thought it was time to do the same for them.

No doubt some will be suspicious of my motives. I’m a Tory, after all – indeed, a former Deputy Chairman of the party. There are two answers to that. The first is that the country needs a strong opposition. Britain will be better governed if those doing the governing are kept on their toes. Moreover, at its best, the Labour Party has been a great force for decency, speaking up for people throughout the country and ensuring nobody is forgotten. We need it to reclaim that role.

The second answer is that you don’t have to trust me – just listen to what real voters have to say in the research that follows. Last month I polled over 10,000 people, paying particular attention to those who voted Labour in 2017 but not in 2019. We have also conducted 18 focus groups in seats Labour lost, with people who have moved away from the party (often feeling that the party had moved away from them). The report includes extensive quotes from these discussions, since they explain Labour’s predicament better than any analyst could. They are all the more powerful when you consider they come from people who were voting Labour until very recently and probably never expected to do otherwise.

We also polled over 1,000 Labour Party members, and conducted focus groups with members of the party and of Labour-supporting trade unions, to see how the Labour movement’s understanding of the election differs from that of the electorate at large and whether – and how far – they think the party needs to change.

From election night on, senior Labour figures have argued that the result was all about Brexit – with the implication that their lost voters will be back in force once that issue is off the agenda. While there is no doubt that Brexit played a huge part in the election, Labour would be wrong to draw too much comfort from that. Yes, many voted to “get Brexit done.” But they also thought Labour’s policy of renegotiation and neutrality was simply not credible: it stemmed from hopeless division and proved the party was nowhere near ready for government.

More serious still for these voters was the principle that Labour had refused to implement the democratically expressed wishes of the people, and often of their own constituents. Brexit therefore became a metaphor for a party that no longer listened to them, taking their votes for granted while dismissing their views as ignorant or backward. “They were saying, ‘it’s the adults talking now, leave the table and we’ll sort it out for you’,” as one former supporter put it. Another linked Labour’s apparent attitude on Brexit to Gordon Brown’s encounter with Gillian Duffy in 2010: “He tarred her with the bigot brush rather than listening to what she had to say. It’s the same with Brexit.” These impressions – of a party unready for office and unwilling to listen – will not vanish just because the Brexit legislation is complete.

It was reported that Labour’s official inquiry “exonerated” Jeremy Corbyn from any blame for the election result. I can only assume this was a compassionate gesture for an already-outgoing septuagenarian leader, because no serious reading of the evidence could reach such a verdict. “I did not want Jeremy Corbyn to be Prime Minister” topped the list for Labour defectors when we asked their reasons for switching, whether they went to the Tories or the Lib Dems, to another party, or stayed at home. Though a few saw good intentions, former Labour voters in our groups lamented what they saw as his weakness, indecision, lack of patriotism, apparent terrorist sympathies, failure to deal with antisemitism, outdated and excessively left-wing worldview, and obvious unsuitability to lead the country.

But the feeling that the Labour Party was no longer for them went beyond Brexit and the Corbyn leadership. While it had once been true that “they knew us, because they were part of us,” Labour today seemed to be mostly for students, the unemployed, and middle-class radicals. It seemed not to understand ordinary working people, to disdain what they considered mainstream views and to disapprove of success. The “pie in the sky” manifesto of 2019 completed the picture of a party that had separated itself from the reality of their lives.

As far as many of these former supporters were concerned, then, the Labour Party they rejected could not be trusted with the public finances, looked down on people who disagreed with it, was too left-wing, failed to understand or even listen to the people it was supposed to represent, was incompetent, appallingly divided, had no coherent priorities, did not understand aspiration or where prosperity comes from, disapproved of their values and treated them like fools.

Despite all this, the defectors we spoke to do not rule out returning to Labour. Indeed, many now clearly relish their new status as floating voters, ready to hold governments to account and take each election as it comes. But they won’t do so until Labour changes, and most expect the necessary transformation to take years. While many Labour members grasp the need to change in principle, it is clear that they would find some of the shifts voters say they want to see – such as a less liberal stance on immigration, or much stricter fiscal discipline – harder to stomach in practice.

This report is not a road map to recovery: different people can draw sharply different conclusions from the same data, and I’m sure that will be the case with this research. But the first step is to come to terms with your starting point. What follows is a pitiless but objective assessment of where that is.