This is the text of a speech I gave in London last Friday covering the background to the current political situation on both sides of the Atlantic, and my perspective on the UK and US elections.

Ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. I don’t know if it’s significant that you have asked me to speak about the political situation on the anniversary of President Kennedy’s assassination, Margaret Thatcher’s removal from Downing Street, and Angela Merkel’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany. We are living through what feels like a momentous time in politics, not just in this country, and I have spent some time trying to make sense of the disruption – and in particular, what the voters make of it all – through my opinion research on both sides of the Atlantic.

This began 15 years ago when, as a longstanding donor to the Conservative Party, I decided it was about time someone made a proper study of why it kept losing general elections – usually after being reassured by the party hierarchy that we were on course for a famous victory. I published the findings under the unambiguous title Smell The Coffee: A Wake-Up Call For The Conservative Party, and on the strength of this, David Cameron appointed me the party’s Deputy Chairman to help ensure its lessons were acted upon. Since stepping down from the role I’ve continued with the research, because it struck me that while commentators were always blessed with an abundance of opinion, real evidence was in rather shorter supply. Another reason was that pointing out the difference between what voters think – and what politicians and pundits think they think – is an appealing way to create a certain amount of mischief.

This afternoon I will talk about what my research says about how things are developing in the early stages of next year’s presidential election in the U.S., and about the general election here whose result we will know three weeks from today. As for what that result is likely to be, I hope you will forgive me if I steer clear of anything that sounds like a prediction. In any case, you would treat any kind of forecast with justified scepticism: in the last two national contests in the UK, most pollsters expected a knife-edge result in 2015 and a comfortable Conservative victory in 2017, but got precisely the reverse. My research aims to understand what is motivating voters and how they are reacting to the various parties, leaders and campaigns – what people are thinking and why – rather than trying to predict whose nose will ultimately end up ahead in the national horse race.

First, I think it’s worth making a few observations about how we got to what seems like an unusually grim and shambolic time in national life. It has become a cliché to talk about the polarization that dominates today’s politics. But the problem is not that people disagree, as they always have. The real problem is that for some time, rather than trying to ameliorate those divisions, politics has emphasized and supercharged them.

In America, people often blame Donald Trump for this. But the truth is that he is the latest in a long line of divisive political developments going back at least to the Clinton era. President Clinton’s failed healthcare reforms, the 1994 Republican Revolution, the impeachment, the hanging chads of the Bush-Gore election, the Iraq War, the financial crisis, Obamacare and the rise of the Tea Party have all combined with the rise of talk radio, the growth of cable news, and the explosion of social media to create the political atmosphere we have today.

The UK has an overlapping recent history of drama: Iraq again, the expansion of immigration from the EU, the scandal over MPs’ expenses, the financial crisis and the years of austerity that followed it, the Brexit referendum and parliament’s inability or unwillingness to implement the result have all been steps on the path to the position we are in today.

In other words, both Brexit and Donald Trump were a long time in the making. It is easy to forget that they are symptoms, not causes. And by the same token, things will not simply change back once the current cast of political characters leaves the stage or when Brexit is settled, if it ever is.

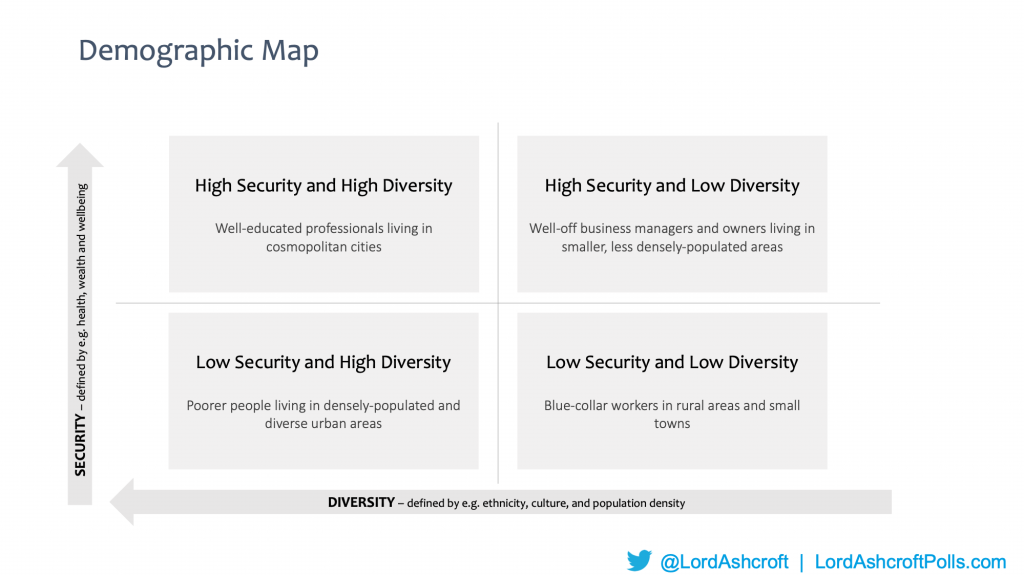

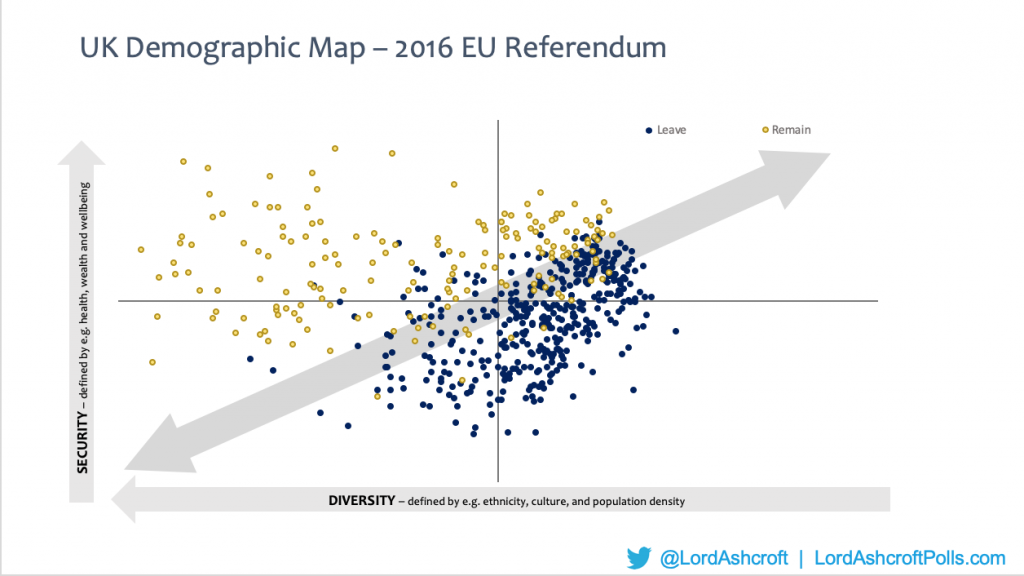

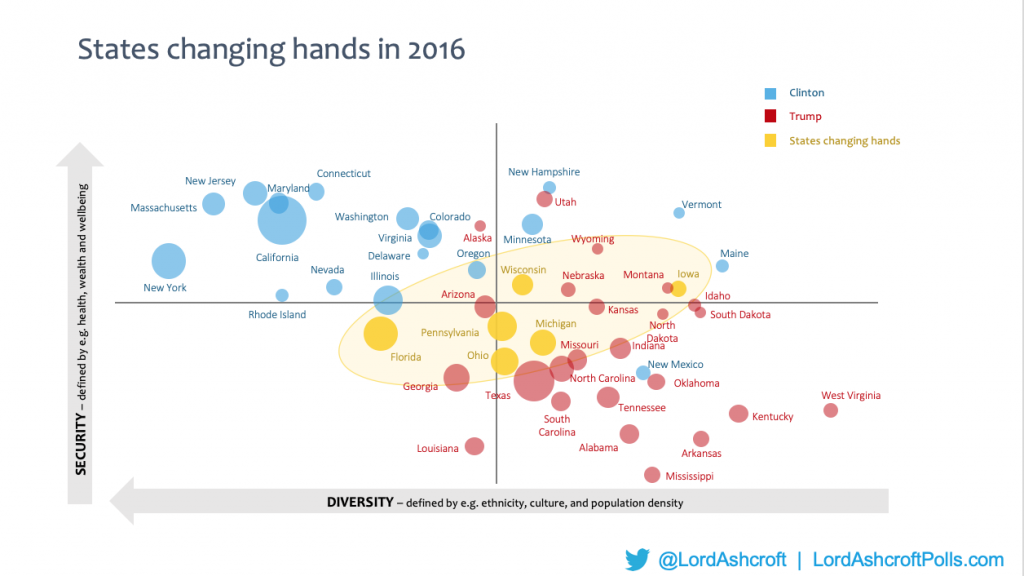

A good way of exploring the effect of these developments, and how dividing lines are moving, is to chart them on a geo-demographic map like this one.

The vertical axis represents security, which includes measures of wealth and wellbeing such as income, occupation and education. The horizontal axis represents diversity – a combination of factors including ethnicity, culture and population density. All these measures are derived from census data. By combining this information with election results and poll findings, we can study how opinion and voting behaviour varies – sometimes in unexpected ways – between people depending on their life situation and location.

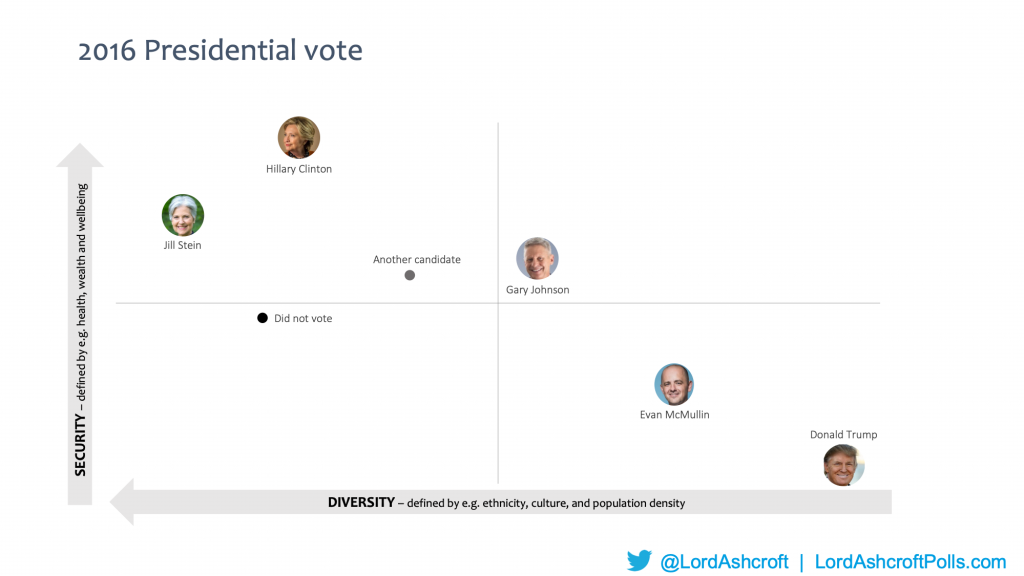

For example, this shows the average position of voters for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump at the 2016 presidential election. The centre of gravity of the Trump vote is firmly in the bottom right hand corner, where we find ‘low security, low diversity’ voters. The Clinton vote is centred in the opposite top-left quadrant, representing a much more diverse and secure set of voters.

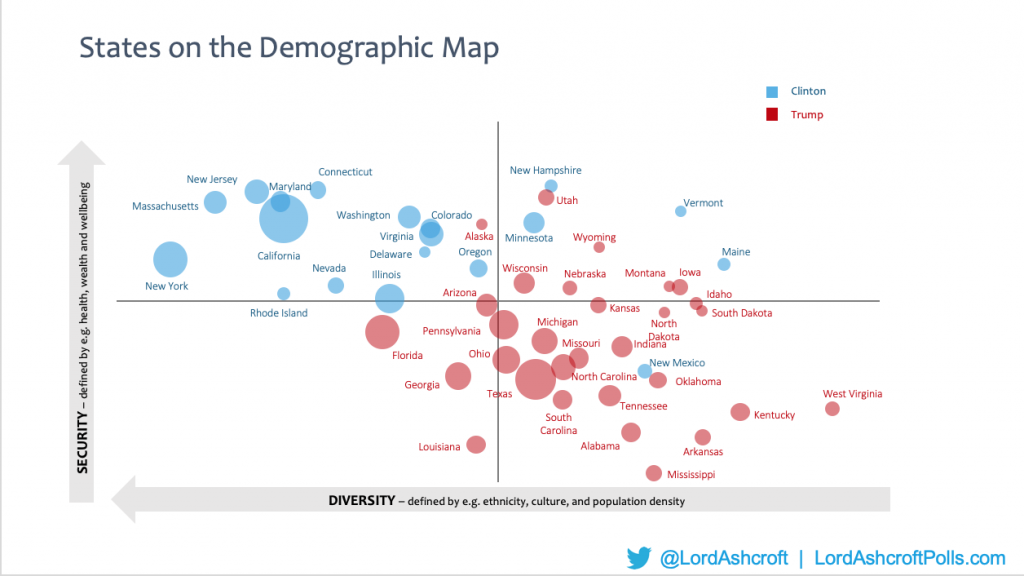

Looked at from a geographic perspective, we can plot states and their relative weights in the Electoral College by their aggregated demographic characteristics. This shows the fault line in American politics in sharper relief, with Democrats dominating the top left, and the bottom right firmly in Republican hands.

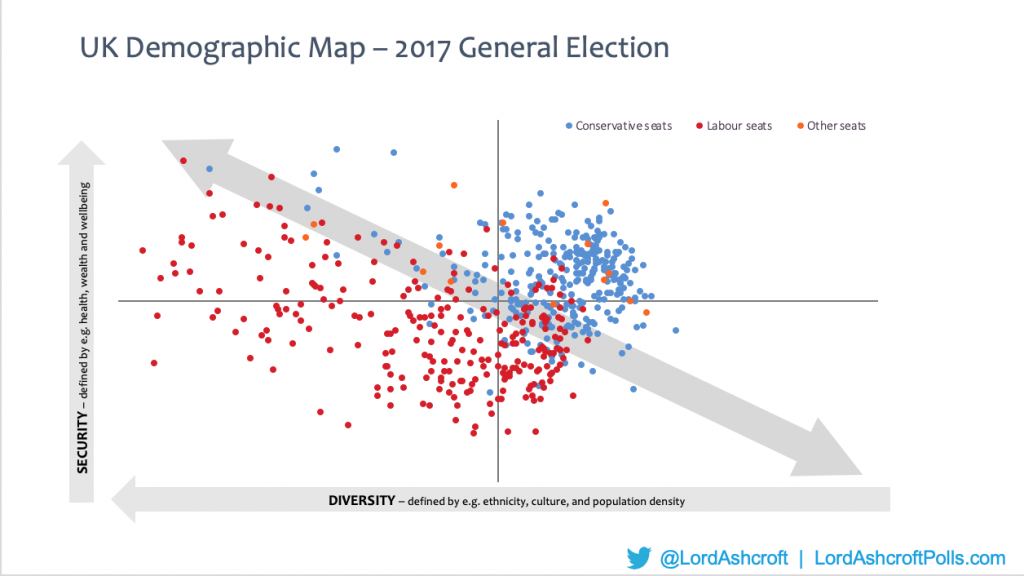

A look at the divide between political parties in Britain shows the divide working in a different direction – which is, incidentally, the way the divide worked in America 30 or 40 years ago. Here we see the constituencies won by the Conservative, Labour and other parties at the 2017 general election. Conservative seats dominate the less diverse but more prosperous top-right quadrant, with Labour holding all but a handful of seats in more diverse, less well-off territory.

But when we look at how those same constituencies voted in the EU referendum, we see the country divided along completely different lines. In demographic terms, Leave support was centred in the poorer and less diverse parts of the country, with support for Remain heavily concentrated in richer, more urban centres and university towns. In terms of attitudes, the divide over Brexit was much more along cultural lines than along traditional left-right ones.

And this is the root of the problem facing British politics at the moment. The Conservatives won their unexpected majority in 2015 by building a coalition of support around their programme to cut the deficit and stabilize the public finances. Two years later, Theresa May called an early general election on an issue that divided the country in a completely different way, in the hope of reassembling the Brexit-voting coalition under the Tory banner.

Looking back to the 2017 election, we can see that Theresa May was at least right about one thing. She foresaw that the getting any kind of Brexit deal through parliament would be a titanic battle, and that the government would need a comfortable majority to see it through. But although she was right in theory, in practice, as we know, it went rather less well than she had hoped.

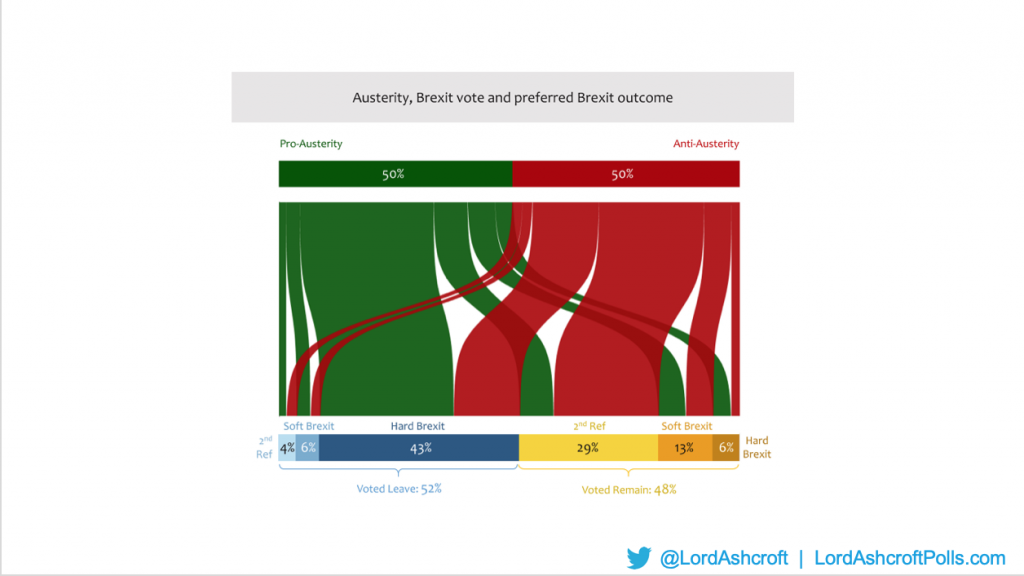

For all the multiple failings of the Tories 2017 campaign, one of the most fundamental reasons for this was that people were not just divided over Brexit, but over the whole preceding decade of political life – in particular, whether or not the government was right to try and balance the books in the way it did after 2010.

As my polling found just over a year ago, only just under half of Leave voters had supported austerity, while one third of the pro-austerity voters who had helped keep David Cameron in office wanted to remain in the EU. This is why Theresa May got the worst of both worlds. Many Remain voters deserted the Conservatives because of Brexit. But most of the Leave-voting former Labour voters who were supposed to take their place refused to fall into line with what they saw as the party of cuts. Wild horses wouldn’t get them to abandon their tribe and vote Tory, however much they supported Brexit. This explains why, so far, no party has since been able to assemble a majority electoral coalition, and why British politics has felt so arduous for so long.

It now falls to Boris Johnson to try and break the deadlock. He has a number of factors in his favour that were missing at the last election. His claim that an election is needed to get Brexit done sounds much more plausible to people than it did when Theresa May tried the same line. The Conservative Party claims to have learned the lessons of the last disastrous campaign, including having a much more realistic list of target seats and not including any potential bombshells in the manifesto. (Well, we’ll see about that when it appears.) Boris is also a natural campaigner and connects with people in a way that his predecessor struggled to do.

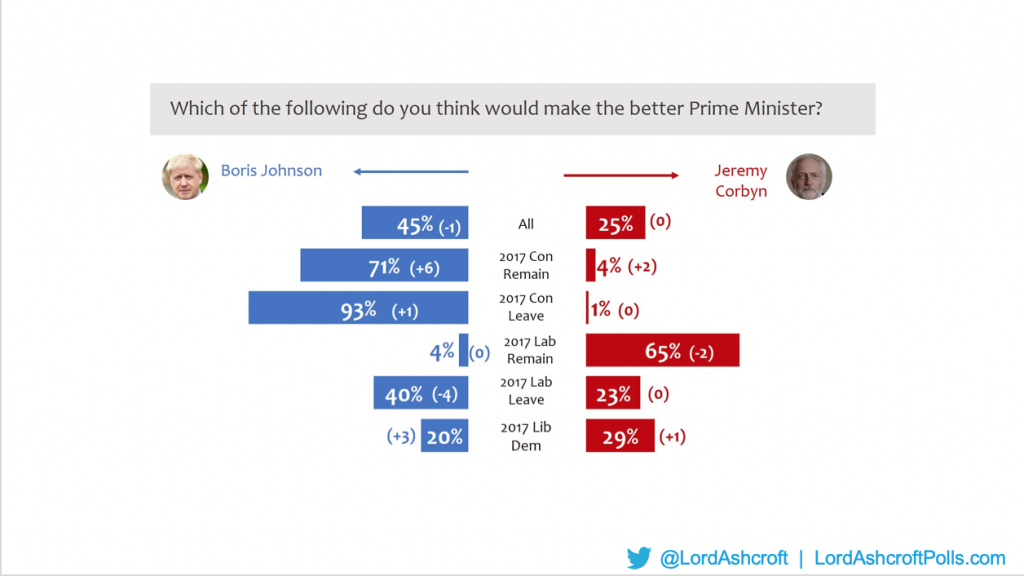

As I found in my most recent poll, completed earlier this week, he maintains a comfortable lead over Jeremy Corbyn as the best available Prime Minister. Only a quarter of voters think Corbyn would do a better job, and 2017 Labour voters who backed Leave in the referendum think Johnson would be the better leader.

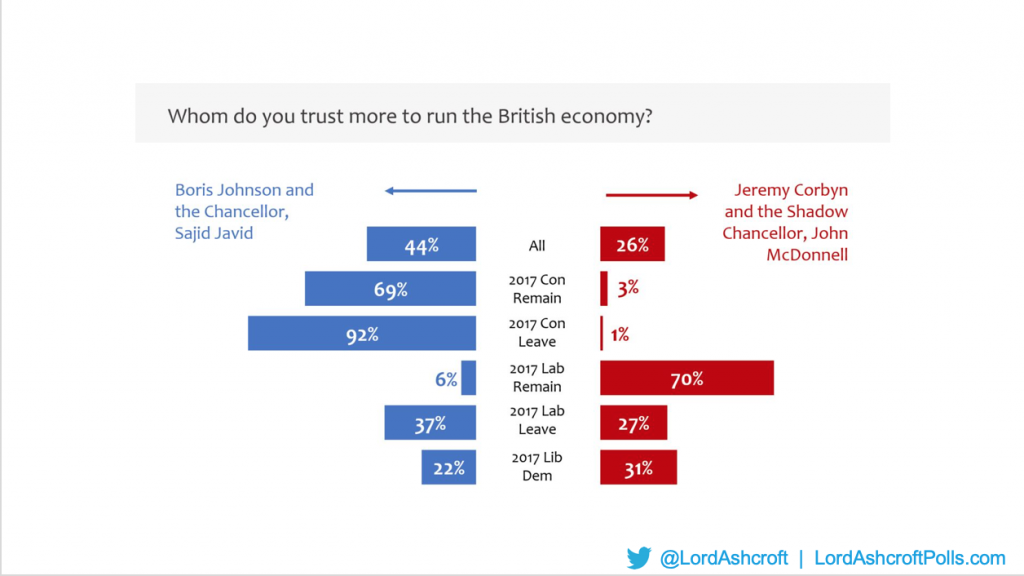

The Conservative team is also more trusted to run the economy than Corbyn and Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell, by a clear margin. Again, Labour Leave voters say they are more inclined towards the Tories on this question. In recent elections, the combination of leadership ratings and trust on the economy has proved to be a good guide to the outcome – often better than voting intention polls themselves.

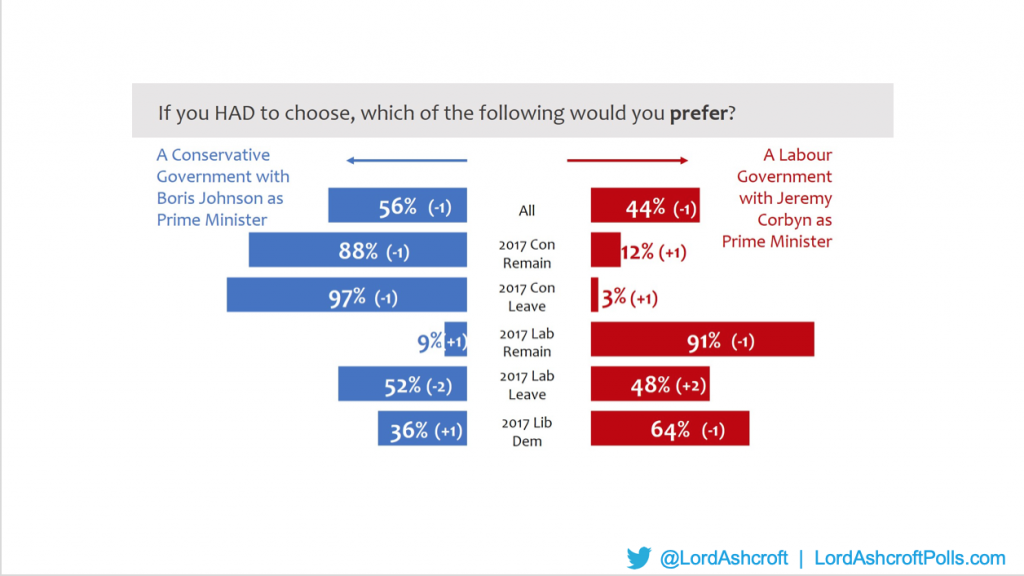

And when we force people to choose between a Conservative government led by Boris Johnson or a Labour government with Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister, at this stage we still find a clear – if not overwhelming – preference for the former. Nearly 19 out of 20 Tory voters from 2017 say want another Conservative government, while only 78% of former Labour voters want a Labour government, and one in five of them would rather have the Conservatives.

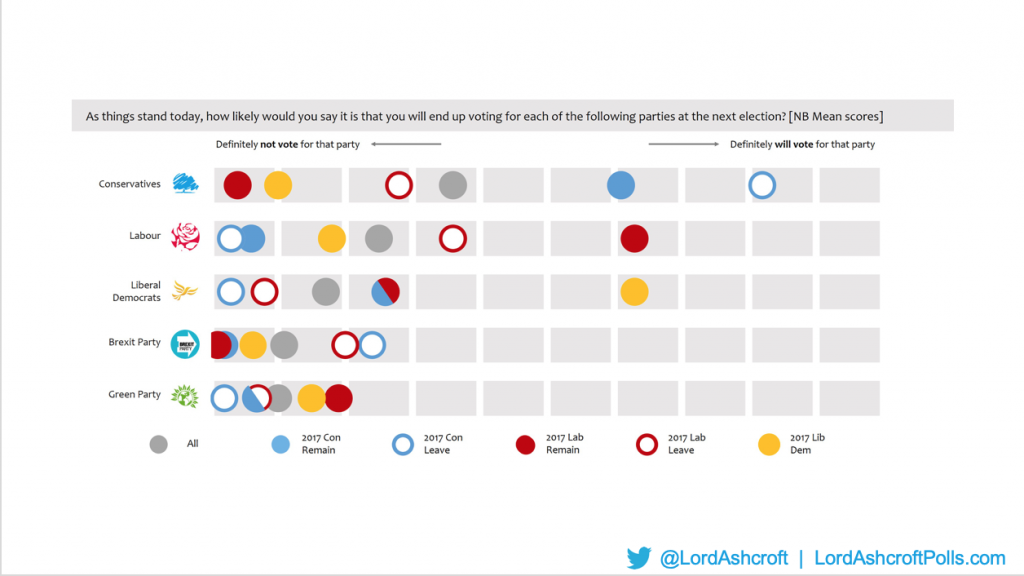

A similar pattern emerges when we ask people about their voting intention. Not which party they will vote for, but how likely they feel they are to vote for each party on a 100-point scale. Here we see Conservatives retaining much firmer support from their 2017 voters than Labour or the Liberal Democrats. And while Conservative Remain voters are less sure about their vote than Tory leavers, as a whole they are still more inclined to stick with the party than abandon it. One reason for this is that many of them think that even though they voted to remain in the EU, we need to honour the referendum result and the Tories are best placed to do so.

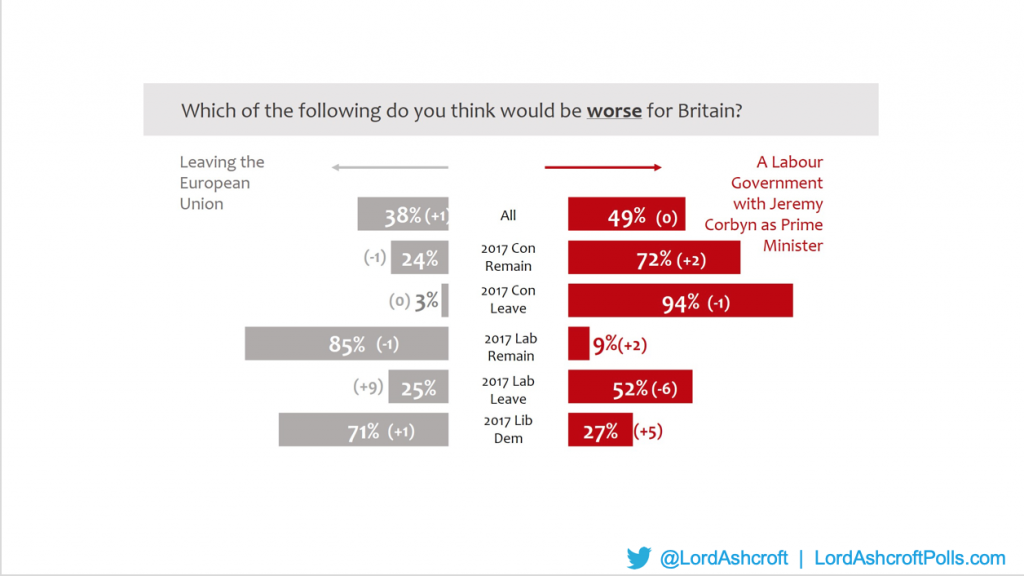

Another reason is that Conservative Remain voters tend to believe Brexit will be a walk in the park compared to the prospect of Jeremy Corbyn in Downing Street. If this election amounts to a decision on whether to stop Brexit or stop Corbyn, most of them think it’s more important to stop Corbyn. More than 7 in 10 of them think leaving the EU would be less bad for Britain than a Labour government with Corbyn as PM – as do a clear plurality of the electorate as a whole.

If this were a normal election, that would be most of what you needed to know: one party with a more popular leader, more trusted on the economy, and with an opponent that scares potential waverers back into line. The trouble is, we don’t seem to have normal elections anymore. For many voters, the decision will amount to a trade-off between their preferred party and their preferred outcome on Brexit.

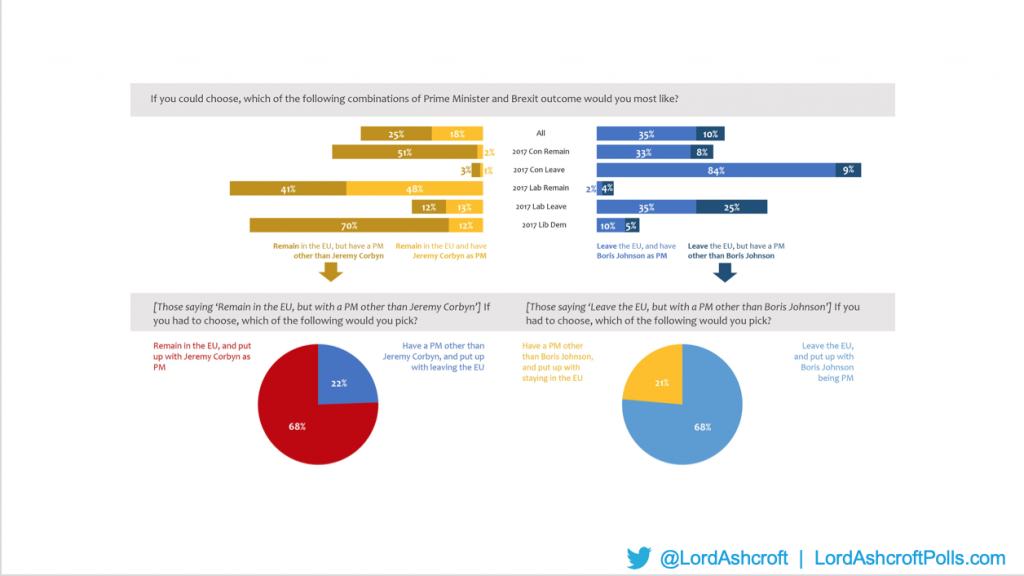

My poll published earlier this week found that while 35% said they wanted Brexit and Boris, a further 10% said they would like to leave the EU but with a different Prime Minister. On the other side, while 18% said they would like to remain in the EU with Jeremy Corbyn as PM, a further 25% said they wanted to remain but with someone else in charge.

In other words, while most of those who want to leave are happy to have Boris Johnson in Number Ten, most of those who want to remain don’t want the PM who would make that possible. Nearly half of all Remain voters – including 41% of 2017 Labour remainers – said they would like to remain in the EU with a PM other than Corbyn. Labour leavers, notably, were more evenly divided than most: 35% wanted Brexit with Boris, with 25% wanting to leave with a different PM.

Both groups whose Brexit preference clashed with their Prime Ministerial one said EU policy was more important to them. Among those who wanted Brexit but with a PM other than Johnson, more than two thirds said that if they had to choose, they would leave the EU and put up with Boris in Downing Street. Exactly the same proportion of those who wanted to remain but without Corbyn said they would put up with him in Number Ten to stop Brexit.

But I think the main lesson from this is that many people are finding their voting decision much less straightforward than usual, and I think this dilemma is something that very large numbers are still wrestling with.

There has been a great deal of talk about a realignment in British politics, with people’s position on Brexit, and the worldview that goes with it, coming to play a bigger part than traditional party loyalties. This was already a factor in the last election, when the Conservative vote was not just bigger but older, whiter, more working class, more modestly educated, and more socially and culturally conservative than it had been before. This was also seen in the distribution of seats, with the Tories losing places like Kensington and Canterbury but making gains in Mansfield and Stoke.

We can expect to see that process continuing this time round, with the Conservatives continuing to pick up some Brexity voters who had never previously considered themselves Tories, while remain-inclined professionals abandon both main parties in favour of the Lib Dems. But this process is far from automatic, and as we are finding on the ground, not everyone is co-operating with the realignment theory.

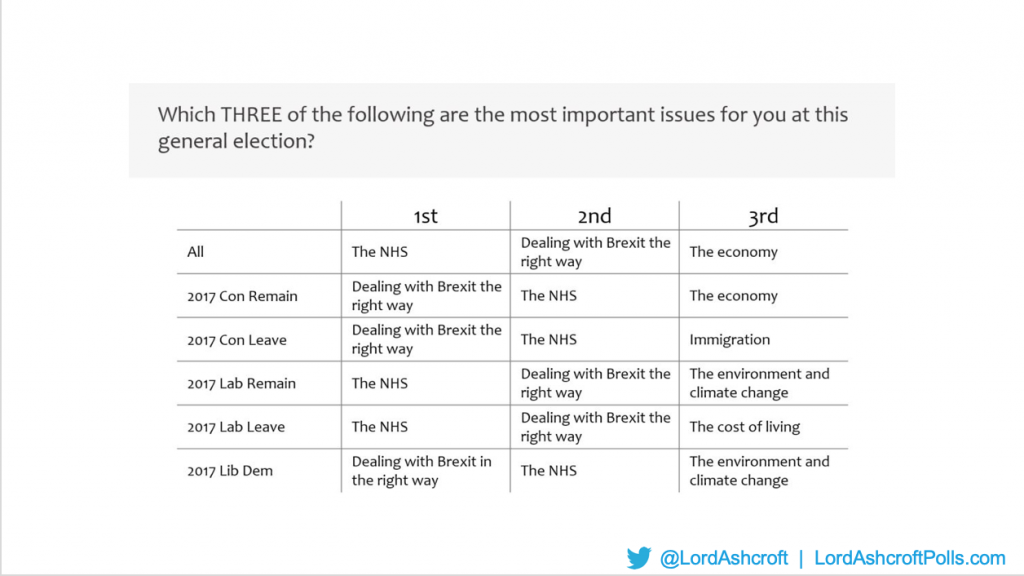

One problem is that, as in 2017, not everyone sees Brexit as the overriding priority. When we asked what issues were the most important to people at this election, we found “dealing with Brexit in the right way” in second place to the NHS. This was especially true of Labour voters, including those who had voted Leave in the referendum. And when we asked separately about potential desirable outcomes from the election, “more funding for public services” trumped “getting Brexit done” among Labour leavers. As we have found in focus groups around the country during the campaign, this – together with recent memories of austerity and a lifelong suspicion of Tories – makes many of them think twice before lining up behind Boris Johnson to get Brexit done.

In theory, the natural home for such voters should be the Brexit Party. They have not so far managed to break through in a way that looked possible after their European election victory. Again, I think there are a number of related reasons for this. One is that voters have long regarded Euro elections as a “free hit” with no real consequences, but they are reluctant to send what look like single-issue parties to Westminster. Another is that most of the Brexit Party’s airtime has been consumed with the long debate over where they would and would not stand, perhaps at the expense of a clear message as to why people should vote for them. And since the decision not to run against sitting Conservative MPs, some have seen the Brexit Party as a kind of front for the Tories.

The Conservatives are hoping that pledges to increase NHS spending and recruit 20,000 new police officers will go some way towards neutralising their problem with former Labour supporters, but here, too they are meeting resistance. “They’ve cut too deep and now they’re saying they’ll give you a little bit back, and it doesn’t wash with me,” was a typical remark, made by a woman in our focus group in Bolton last week. And as another in Stoke put it, “there’s a lot I don’t agree with Jeremy Corbyn about, but I think Labour will still be for the working man.”

That’s not to say that Labour’s plans are taken at face value either, whether on free broadband, the four-day week, or the promised bonanza for public services. Indeed, for some they are a reminder that the outgoing Labour Chief Secretary in 2010 left a note to his successor apologising that there was no money left. But in some quarters – party brands being what they are – while Tory promises sound cynical, Labour’s are at least taken to signal good intentions, even if they might not all come to pass. As another young woman quite literally told us last week, “Labour said something about bringing back bursaries for nurses. I don’t think they’ll do it, but it was nice that they thought of it.”

But it’s not just the Conservatives who are often finding their overtures to Labour voters spurned. The Liberal Democrats are finding the same problem. Exasperated though some Labour remainers are by the leadership’s mysterious refusal to say whether it would campaign for or against any new deal it managed to negotiate with the EU, relatively few are attracted to the Lib Dems’ unambiguous commitment to revoking Article 50. There are two main reasons for this. One is that though they would like to remain, they feel there is something not quite right about simply acting as though the referendum never happened.

The other reason is that they simply cannot forgive or forget the Lib Dems for the coalition in 2010. As one left-leaning voter told us in the target seat of Cambridge, “I voted Lib Dem in that election and they ended up in David Cameron’s government. It’s not what you vote Lib Dem for”. The party’s reversal on tuition fees – though it was now nearly ten years and four leaders ago – remains the iconic example of the broken political promise for a generation of voters.

All of which goes to show that although things are evolving, the old left-right divide, and especially the power of party brands to attract or repel voters, are by no means redundant.

So what is going to happen?

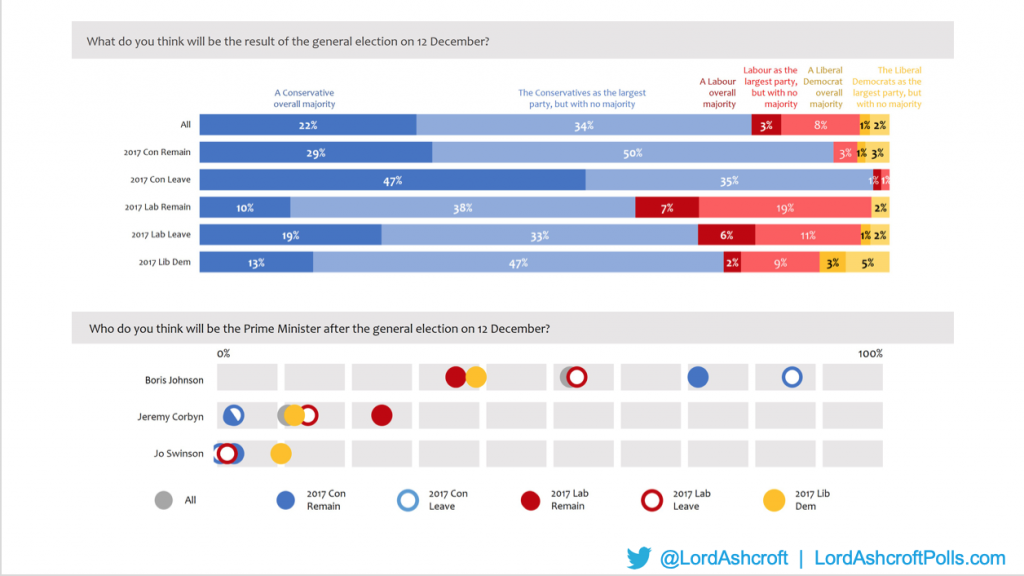

When we asked people last weekend, we found more than half of respondents believing the Conservatives would be the largest party, but only just over one in five expecting a Tory overall majority. The next biggest chunk, a quarter of all voters, said they didn’t know.

To me, the most striking thing here is how few expect Labour to come out on top. Only just over one in ten think the party will have the most MPs, and only 3% expect an outright Labour victory. This in itself might make the Tories uneasy. It’s hard to galvanise your support with the peril of an opposition victory whose prospects seem so remote. We have heard some of this in focus groups too. People who are not enamoured of Jeremy Corbyn but want an excuse not to vote Tory ask “what’s the worst that could happen?” and reassure themselves that he’s not going to have the majority to do anything too daft. The hazard here for the Conservatives, who will need a clear majority to function at all, it obvious.

At this stage, I agree that the fundamentals are in Boris Johnson’s favour – but with three long weeks to go, it still feels to me as though this election is somehow not settled yet.

But at least we will know the outcome in three weeks’ time. We will need to wait nearly a year for the result from across the Atlantic. As I said in an article last weekend, anyone thinking of betting the house on that election had better make sure they have a friendly neighbour with a spare room, just in case.

First, here is what the battleground looks like on our demographic map.

These are the states that changed hands at the last election in 2016. As you can see, they are all close to the centre, and along the line that separates the cosmopolitan, liberal top left from the more conservative and less diverse bottom right.

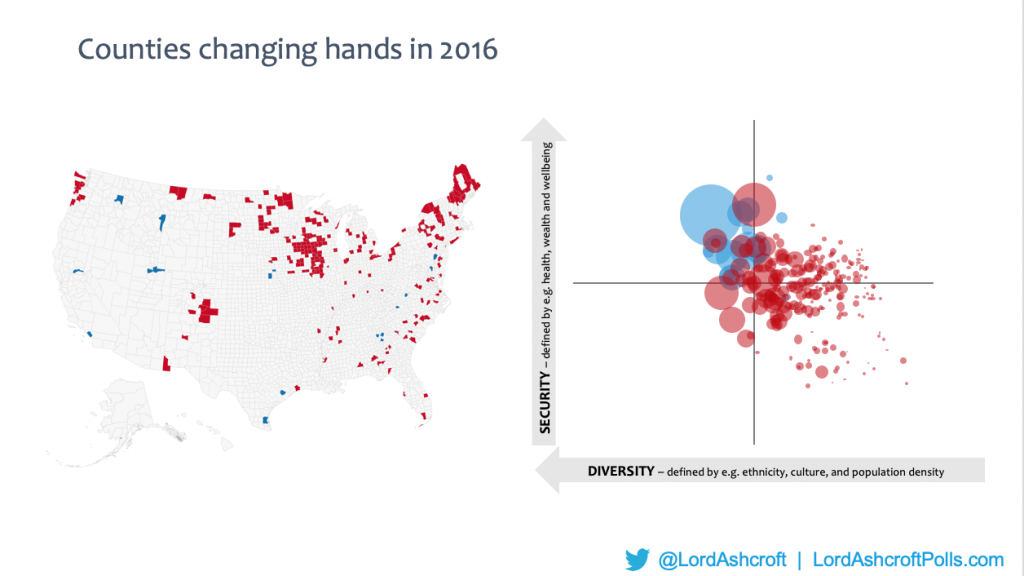

The point is made even more starkly when we look at the individual counties that flipped one way or the other. If the familiar map on the left shows where these places were, the one on the right shows what they were like, and where the divide falls. In geographical and demographic terms, this is where the battle for 2020 will once again be played out.

In political terms, we know what one side is going to look like. My research has consistently found most of those who voted for Donald Trump saying he has met or exceeded their expectations. They point to a thriving economy, which they put down to his tax reforms and deregulatory agenda, conservative appointments to the Supreme Court, a firm stance on immigration and border control and what they see as his determination to stand up for America in the world. And while his opponents spent the last campaign and much of his presidency complaining about his personal conduct, even those who voted for him only reluctantly tend to see this as a price worth paying for someone who is keeping his promises, shaking things up in Washington and standing up for them.

But there are Republicans voters in play. These are most likely to be found among those who switched to Trump having previously voted for Barack Obama; those who voted for him only grudgingly in order to stop Hillary Clinton; those who couldn’t bring themselves to vote for either candidate in 2016; and the moderate suburban voters who switched sides or stayed at home in last year’s midterms to give Democrats control of Congress. Many of these voters are weary of his antics, and some worry about what a second term would bring. They are open to an alternative.

The question is, will his opponents be able to grasp the opportunity this presents? In my polling among American voters since 2016 I have found Democrats to be in a furious and increasingly radical mood. Rather than reach out to those who backed Donald Trump, many have yearned to head in the opposite direction and adopt the most progressive candidates and platforms they can find. But on the basis of my more recent research, including focus groups of primary voters in New Hampshire last month, I think the looming election is starting to concentrate minds. They know they are going to have to make some kind of compromise, so the question is what kind of compromise it will be.

I found very little enthusiasm for any of the frontrunners. Joe Biden is touted as the safe choice, but our participants thought he lacked new ideas and was showing his age with increasingly regular “senior moments”. Many wondered why President Obama had not endorsed him, after eight years alongside him in the White House. While there is still affection and respect for Bernie Sanders, potential backers worry about his age and health – “you’d be voting for his Vice President,” as we heard more than once. People also wondered how he would fund his healthcare and college plans.

This was also a problem for Elizabeth Warren, whom few had warmed to though she seemed capable: she was described as “shrill,” and many found her claims of Native American ancestry bizarre. The candidate most often mentioned positively and spontaneously was Pete Buttigieg, who has recently taken the lead in some polls on the Iowa caucus. Many thought him smart, constructive, impressive and likeable, though some worried about his relative youth and inexperience.

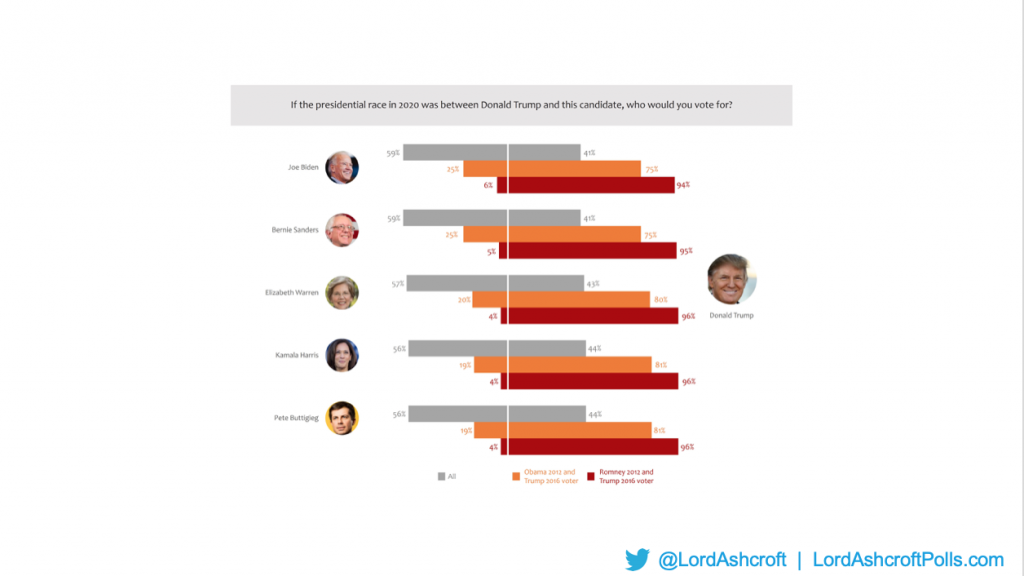

At this stage, many national polls suggest that any one of the Democrat frontrunners could beat President Trump next November. And these figures from my October poll show around one in five Obama-Trump voters saying they might vote for Warren, Kamala Harris or Mayor Pete in a head-to-head with Trump, and one in four saying they could back Biden or Sanders.

But at this stage, such findings should be taken with a wheelbarrow of salt. Most voters have other things to think about and will not properly tune into the process at least until they have a firm nominee to compare against the President. But speaking to undecided former Trump voters last month, we found that the main message that drifts across from the Democrat camp is “free this, free that.” While healthcare is one of their biggest concerns, they worry about the tax implications of Medicare for all and free college. Suburbanites may yet decide they like their hard-earned dollars more than they dislike Donald Trump’s Twitter feed.

Many of them also feel that the Democrats still regard them as a “basket of deplorables” for having had the temerity to vote for Trump in the first place. This still rankles, and makes it harder for the party to recruit them. And while they still broadly see President Trump as a change in the right direction, the current most likely alternatives sound to many like either a change back to how things were, in the case of Biden, or a change in a wrong and potentially threatening direction, in the case of Warren and Sanders.

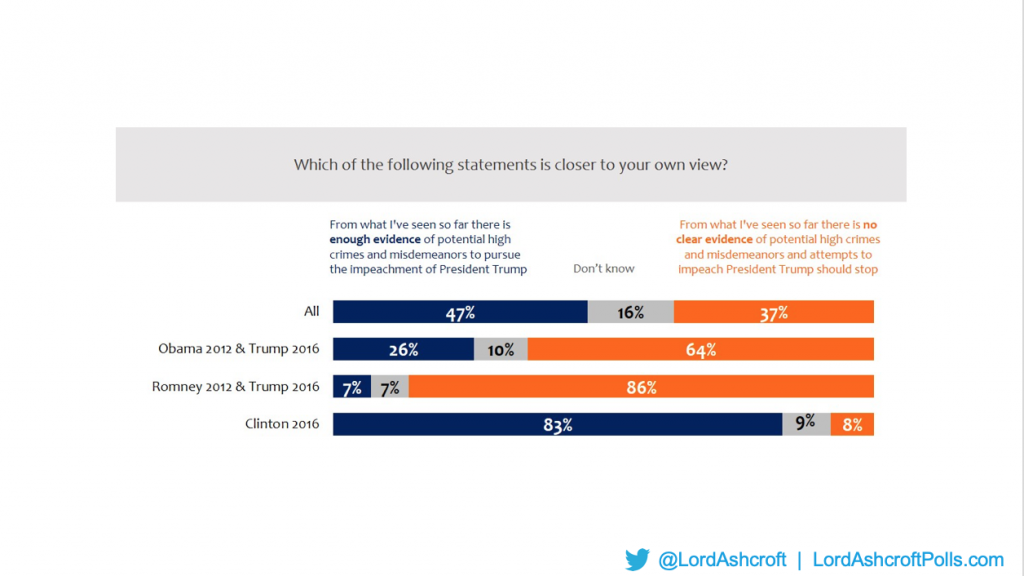

Meanwhile, we have the diverting spectacle of the impeachment hearings. In my research in the early stages of the process I found some Democrats were very excited about what would unfold. Even if the Senate fails to convict and remove him from office, they argued, voters would see at last what a terrible candidate he is. This is part of a longstanding habit I have observed – after every presidential controversy, Trump’s opponents think that surely now people will see what a terrible mistake they have made by voting for him. But others worried that impeachment will simply galvanise wavering Trump supporters, and I think they have a point.

Some Republicans – and particularly the Obama-Trump voters I mentioned earlier – think the allegations are serious and worthy of investigation. But the more general reaction from Trump supporters is “oh, again?” Having seen Trump’s every move since inauguration day treated as a national scandal, many see the impeachment simply as the culmination of a three-year “witch hunt”, making them all the more determined to keep him in office.

The title of my talk has been Political Disruption: the voters’ perspective, and it is hard to think of anything more politically disruptive than attempting to remove a sitting president from office. But it’s also tempting to think that the disruption will be over when the impeachment saga is over, and Trump is re-elected, or isn’t, and Brexit is concluded or cancelled. For good or ill, I can’t see that being the case. Those of us who study these things will have plenty to keep us interested for some time to come.

Thank you very much for listening.