As the government embarks on two years of grueling EU negotiations following the triggering of Article 50, I decided now was a good time for a detailed look at the political landscape – and what voters expect from the Brexit deal. Here’s what I found from my 10,000-sample poll and focus groups around the country.

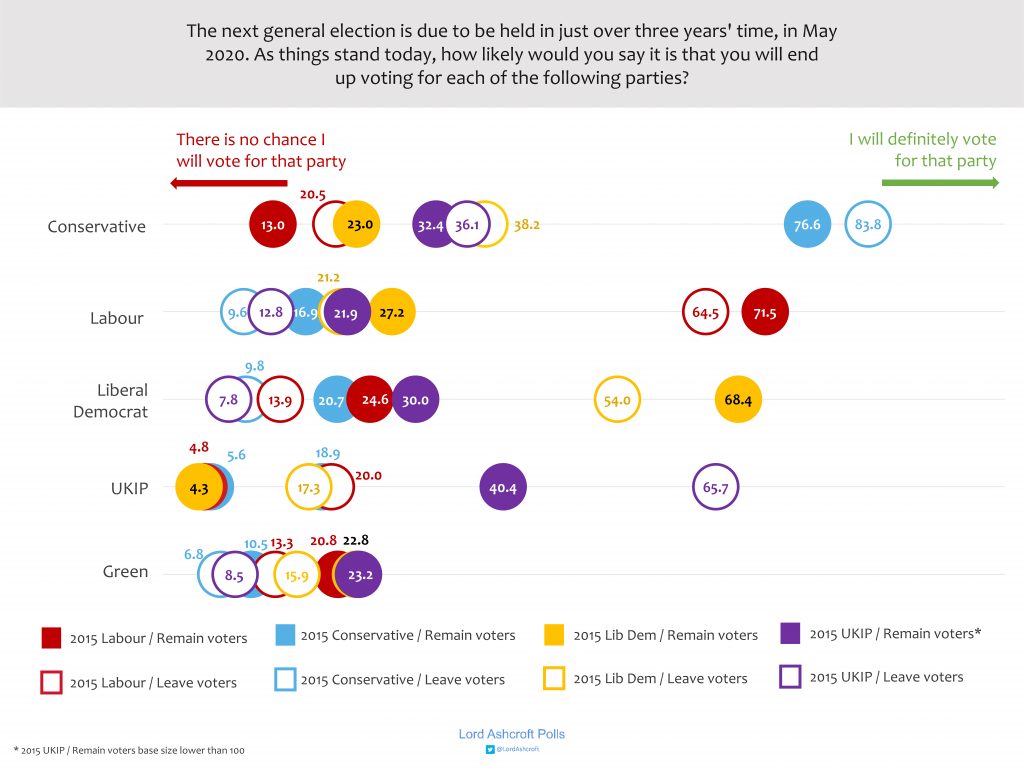

With three years to go until a general election, rather than asking people how they would vote tomorrow we gave them a little more leeway, and invited them to give their likelihood of voting for each party on a 100-point scale. The answers look like this:

Those who voted Conservative in 2015 were the most likely to say they would stay with their party, however they voted in the referendum. However, 2015 Tories who had voted Lib Dem in 2010 gave a lower likelihood of staying with the Conservatives (64.3), and a higher chance of returning to the Lib Dems (32.0) – though this still left them twice as likely to stay as to switch. Labour’s 2015 voters were less sure that they would stay put. Those who had voted Remain gave the highest score to the Lib Dems as their alternative party; for those who had voted Leave, the Conservatives were the most likely alternative.

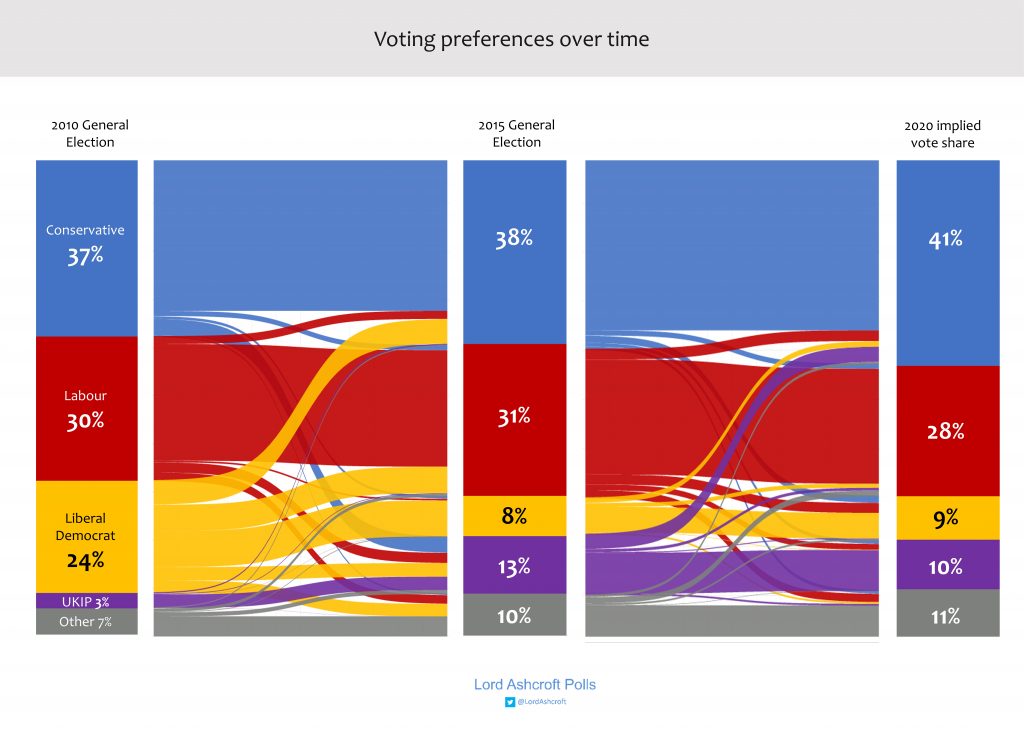

Including only those voters who gave a clear preference for one party in their 100-point scale gives implied current voting intentions of Con 41%, Lab 28%, Lib Dems 9%, UKIP 10%, Others 11%. This chart illustrates how voters flowed between parties from one election to the next since 2010 (though for 2015 and 2020 only includes those who voted at the previous election):

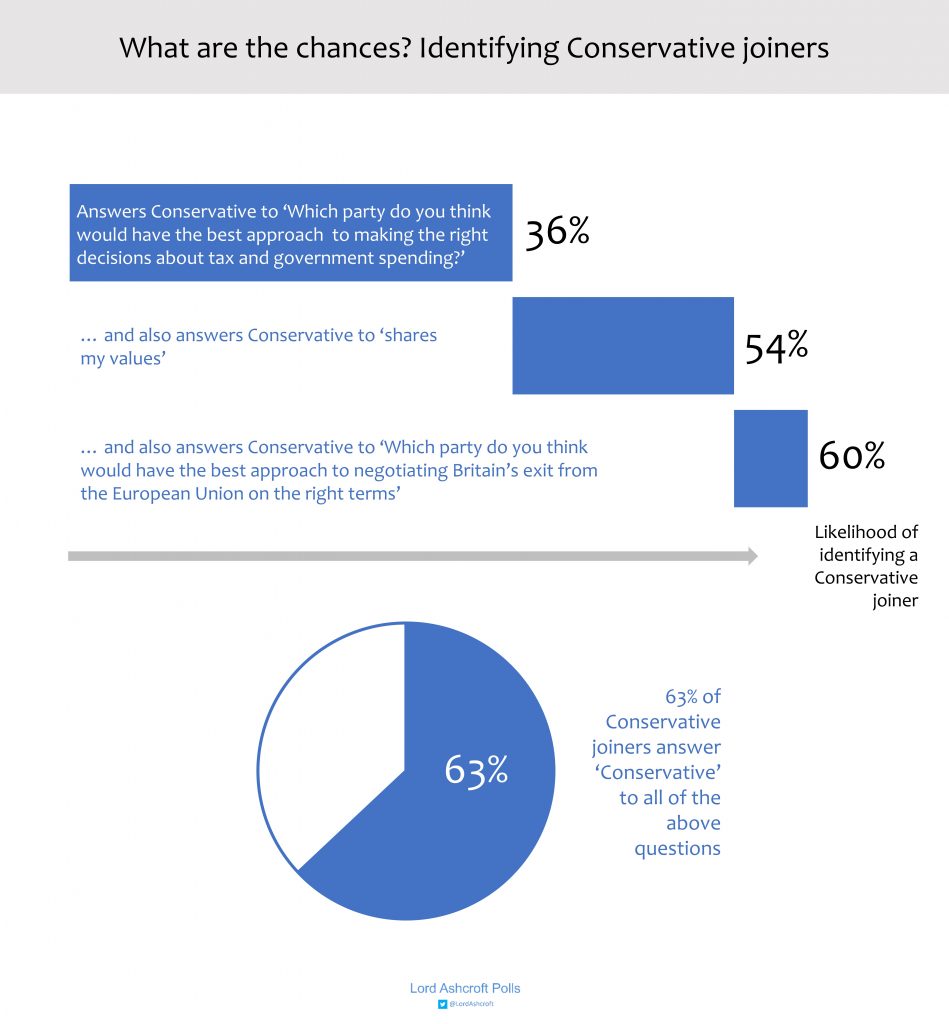

We looked in more detail at voters who said they had switched parties – that is, gave a higher probability on their 100-point scale of voting for a different party in 2020 from the one they voted for in 2015 – to see what they had in common, and what were therefore the most important factors in their move. For Conservative joiners (who voted for a different party at the last election but now say they are more likely to vote Tory than anything else), the pattern looks like this:

If someone did not vote Conservative in 2015 but now say the Tories are the most likely to make the right decisions about taxes and public spending, there is a 36% chance they are a Tory joiner. If they also say the Tories are the party most likely to share their values, the chance rises to 54%. If, on top of that, they say they think the Tories have the best approach to negotiating Brexit, the chance of them being a Tory joiner rises to 60%. This combination of views accounts for nearly two thirds (63%) of those who are switching to the Tories having voted for a different party in 2015. (Similar analysis of Conservative defectors, Labour joiners and Labour defectors is detailed in my full report).

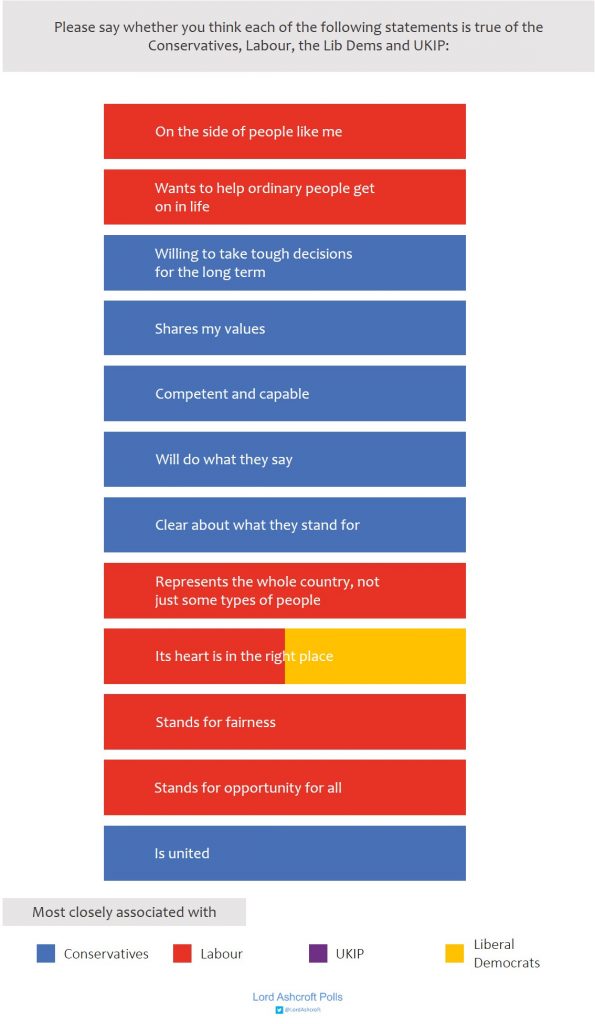

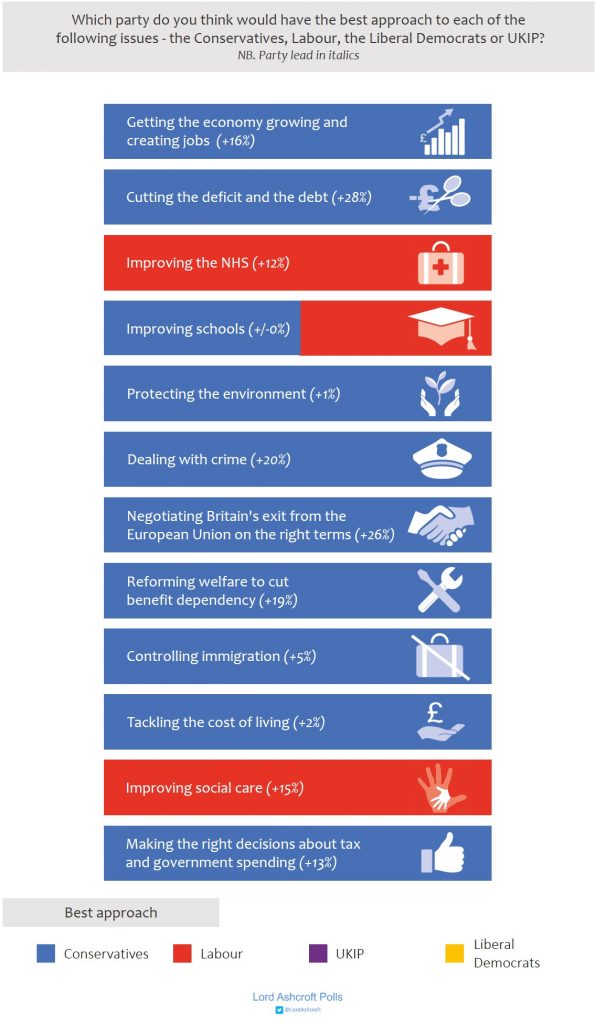

My poll found Labour retaining their traditional leads on fairness, opportunity for all and helping ordinary people get on in life, but the Conservatives were considered by huge margins to be more competent, willing to take tough decisions, and clear about what they stand for. And while Labour were thought the best party on the NHS and social care, the Conservatives were more trusted on all other policy issues – especially cutting the deficit, negotiating Brexit, crime, welfare reform and the economy:

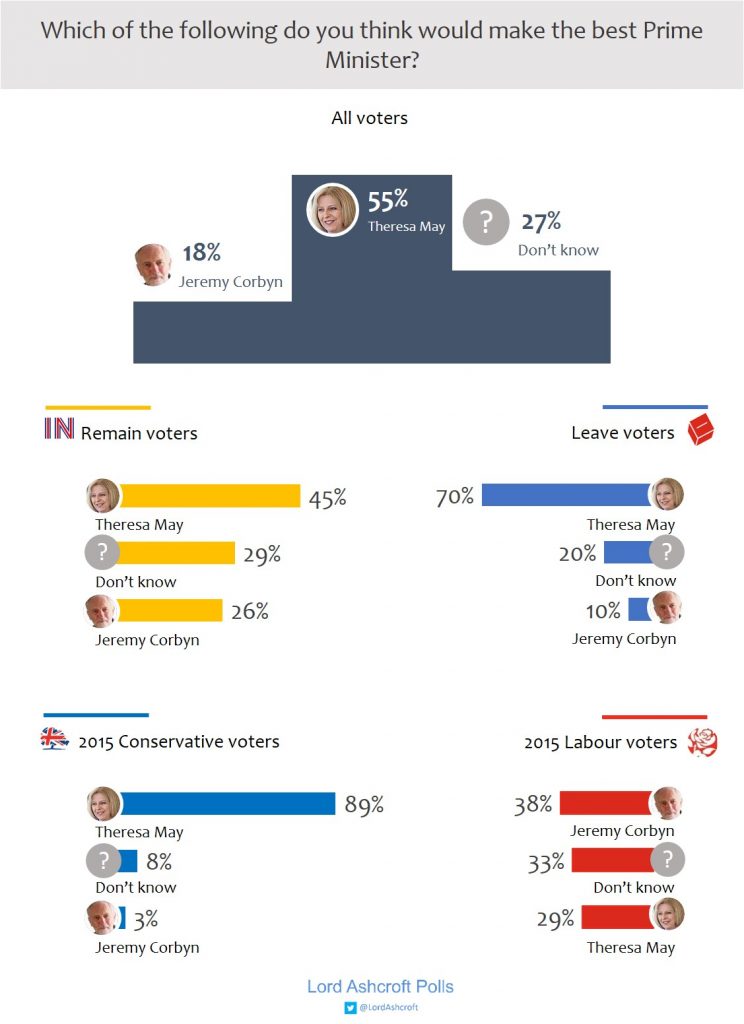

Theresa May had a 37-point lead over Jeremy Corbyn on the question of who would make the best Prime Minister. While nine out of ten Conservative voters chose May, only 38% of 2015 Labour voters named Corbyn. Those who had voted Labour in at the election and Leave in the EU referendum preferred Theresa May by 40% to 30%:

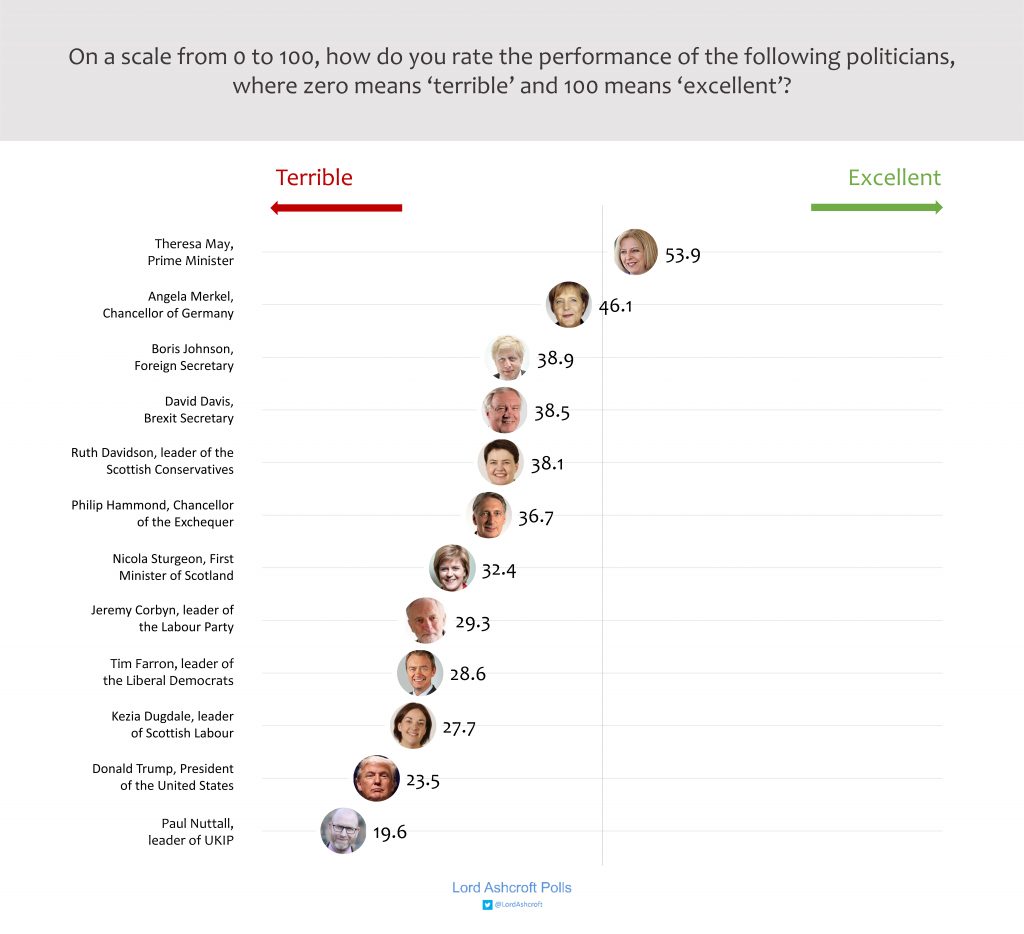

In a longer list of domestic and international politicians, Theresa May was the only one whose performance voters rated above 50 out of 100 – just ahead of German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Jeremy Corbyn scored slightly ahead of Tim Farron, Paul Nuttall and Donald Trump:

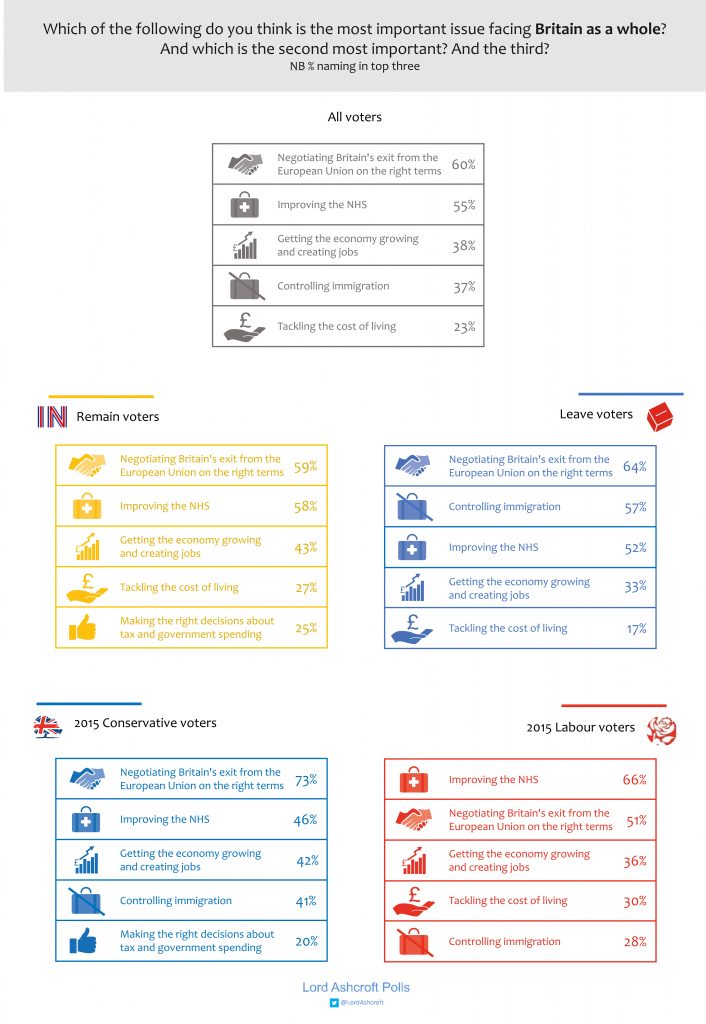

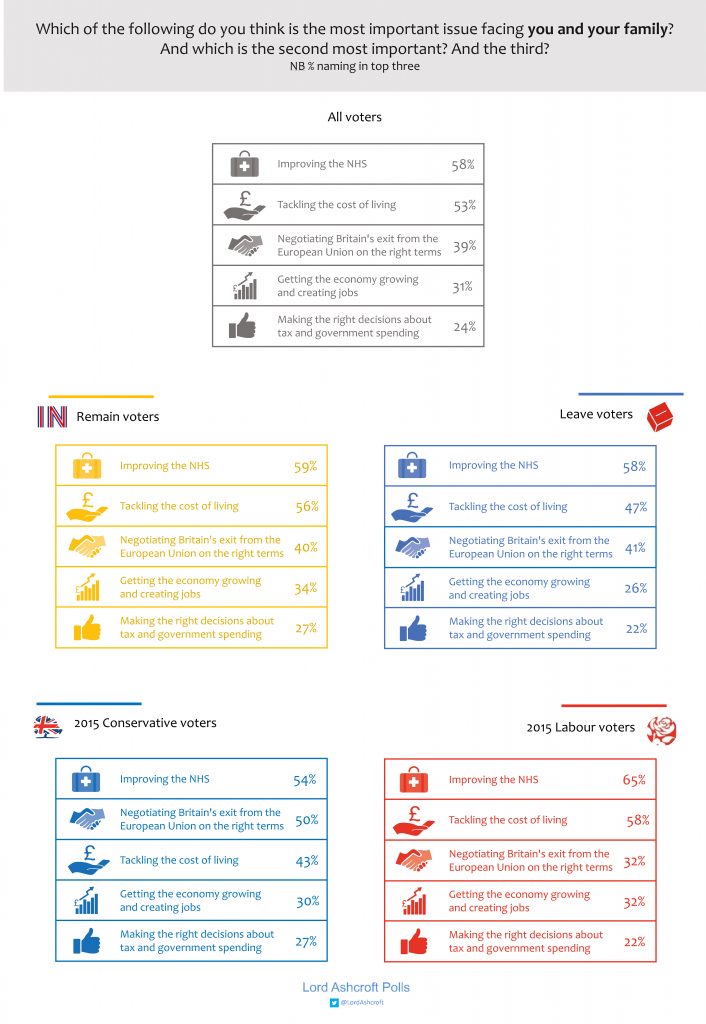

Asked what were the most important issues facing Britain as a whole, six in ten of our poll respondents named “negotiating Britain’s exit from the European Union on the right terms” among the top three. This put it at the top of the priority list for the country, both for Remain and Leave voters. However, when asked what mattered most to “you and your family”, the Brexit negotiations fell to third place behind “improving the NHS” and “tackling the cost of living”. Only 39% of all voters named it among the top three issues on this measure:

When it came to negotiating the terms of Brexit, three quarters of those who voted to Leave (but only one third of Remain voters) put their level of confidence that Theresa May and her team would be able to get a good deal at more than 50 on a 100-point scale. Leavers put their mean level of confidence at 66, and remainers at just 39.5.

However, less than a quarter of voters overall, and fewer than four in ten Leave voters, said they thought the UK had the stronger hand in the negotiations. Most thought either that the two sides were evenly matched, or (as was the case for nearly two thirds of Remainers) that the EU had the advantage.

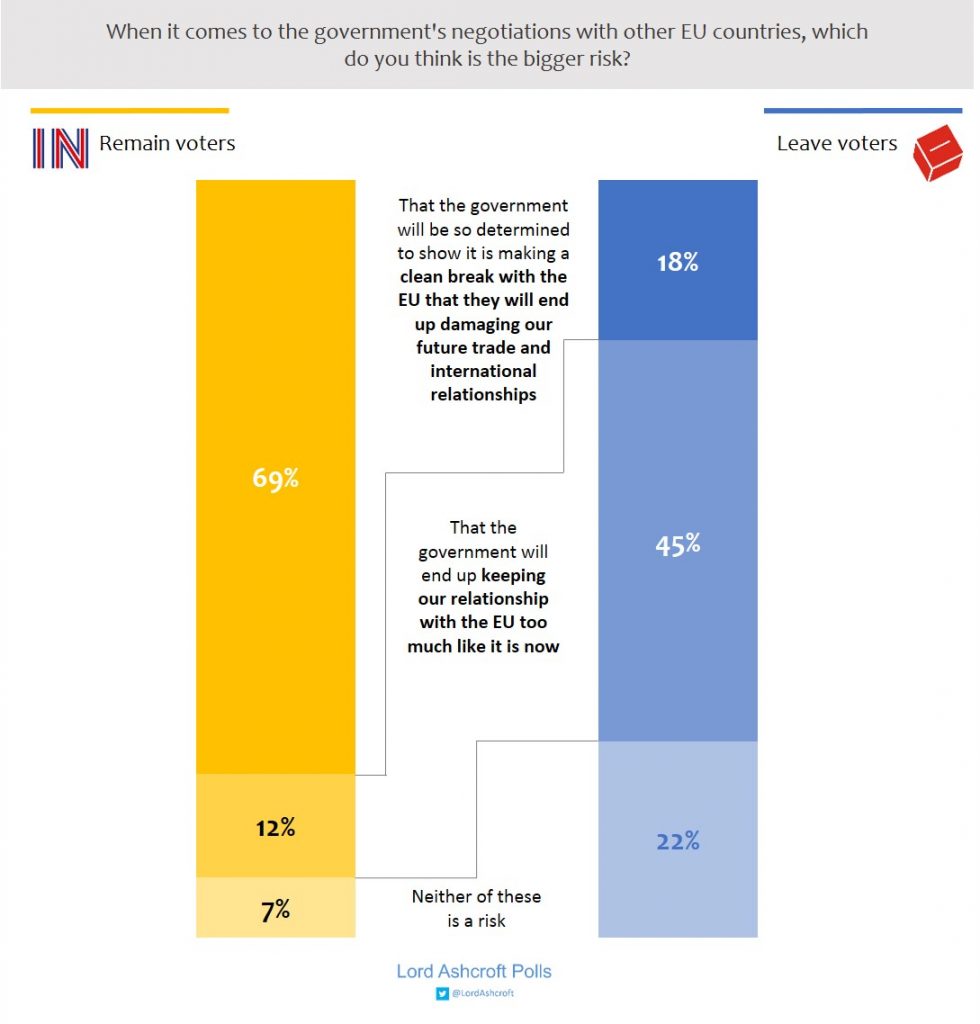

In the negotiations, those who had voted Leave thought the bigger risk was that the government would end up agreeing to keep our relationship with the EU too much like it is now. However, nearly one in five Leavers, and nearly seven in ten Remainers, were more worried that the government would be “so determined to show it is making a clean break with the EU that they end up damaging our future trade and international relationships”.

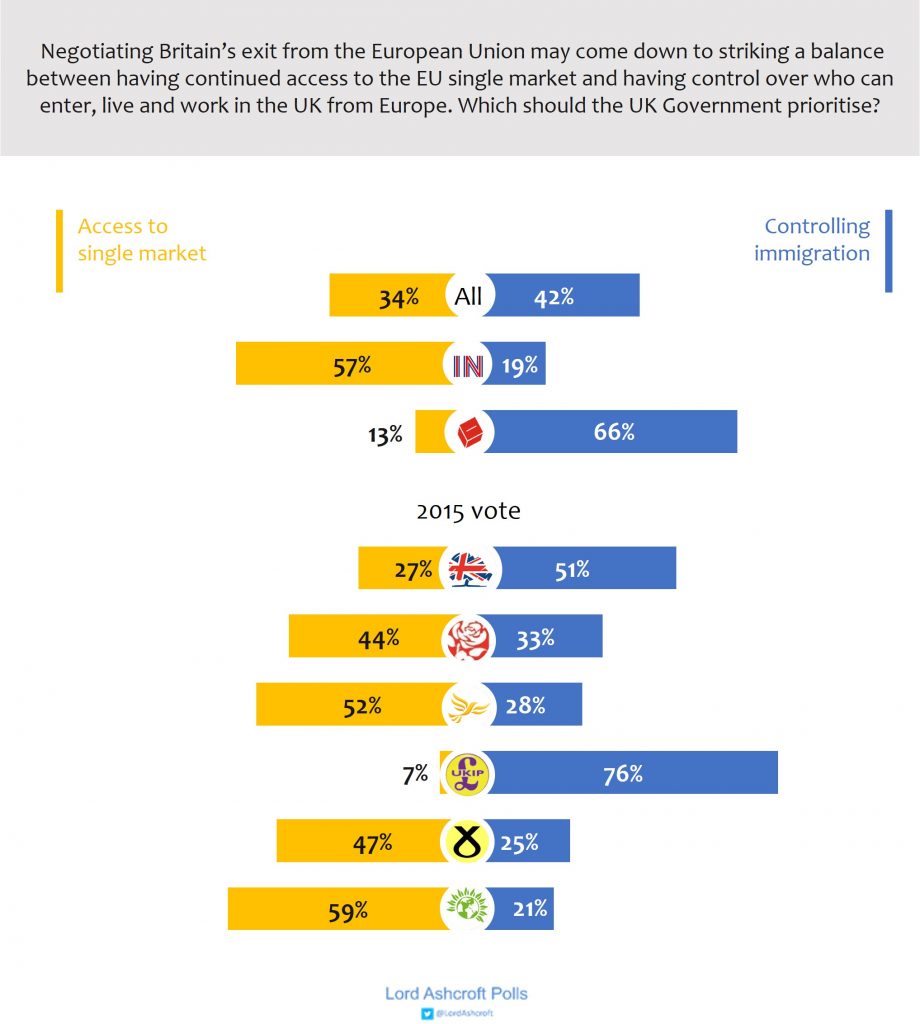

If the negotiations came down to striking a balance between access to the single market and controlling immigration, most voters would give the latter higher priority. As well as two thirds of Leave voters, nearly one in five Remain voters (including three in ten Remainers who voted Tory in 2015) said controlling immigration was more important.

One reason for this is that many Remain voters simply agreed that stricter controls were needed on immigration, including EU immigration. Second, even Remainers who did not feel strongly about immigration themselves often argued that this had been one of the most important reasons for the referendum result, and it would be both wrong and politically impossible for the government to ignore this. Third, many felt the trade side of things would take care of itself: EU countries had too much to lose from putting up barriers to trade with the UK, so no big concessions would be needed to ensure that trade continued freely.

On the question of EU nationals already in the UK, just over half (including nearly three quarters of Leavers) thought their future status should be linked to that of UK nationals living elsewhere in the EU. More than six in ten Remain voters, however, thought the government should guarantee that they could stay, irrespective of the deal reached over British people living abroad.

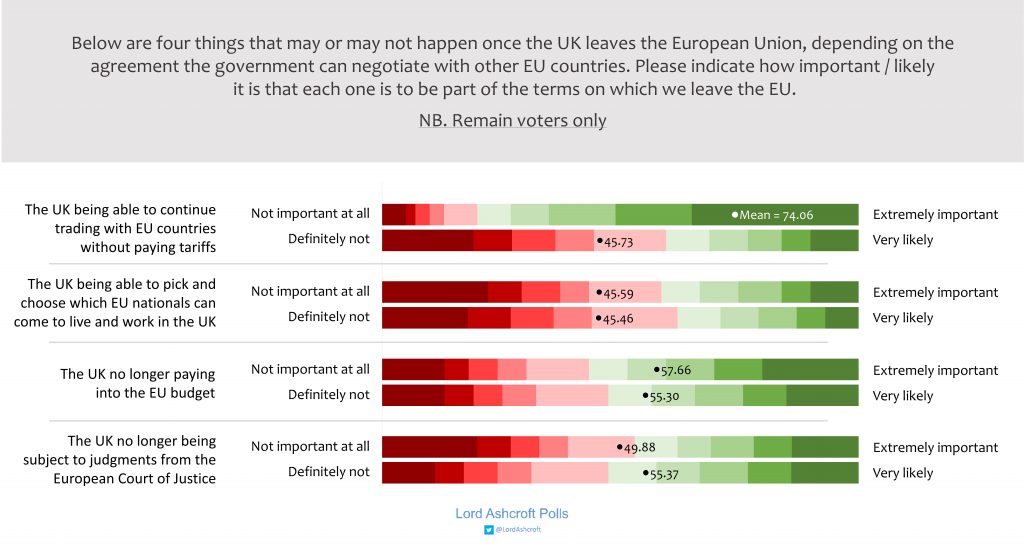

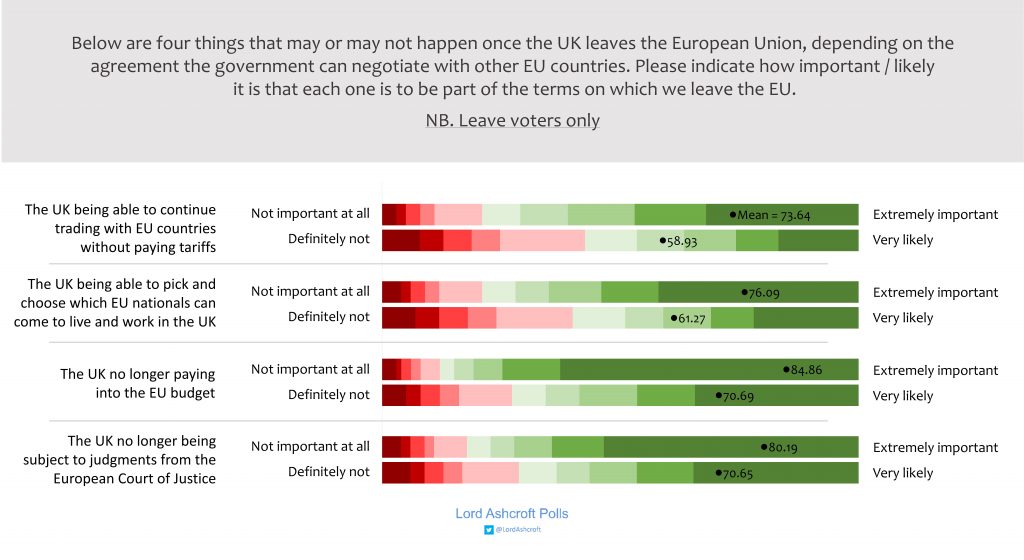

To assess what people hoped and expected to get from the Brexit negotiations we asked both how important and how likely it was that four potential objectives be achieved: ending contributions to the EU budget, no longer being subject to judgments from the European Court of Justice, being able to pick and choose which EU nationals could come to live and work in the UK, and continued tariff-free trade with EU countries.

For Remain voters, the most important objective was to continue trading without tariffs, though they put the chances of this being achieved at less than 46/100.

Those who had voted Leave in the referendum thought all four objectives very important. They gave the highest scores to no longer paying into the EU budget (85/100) and no longer being subject to the ECJ (80/100). These were also the two outcomes they considered most likely to be part of the UK’s eventual departure terms. They also thought it more likely than not that the UK would have the right to control EU immigration, and to continue trading with EU countries without paying tariffs.

This presents a real challenge to the government. Most voters feel we will not really have left the EU if we continue to pay for it, have to follow its laws, and continue to permit free movement. At the same time, many see no reason why our trading relationship should continue exactly as it is now. If the government thinks otherwise, it must be careful not to let expectations get out of hand.