Former Conservatives who have moved away from the party are divided as to whether they want a strong Tory opposition or “a huge defeat so they get the message”, according to my latest campaign polling. Meanwhile, Rishi Sunak being deprived of Sky TV was the third most noticed story of recent days and fewer than 1 in 3 voters think Labour would bring more stability, shorter NHS waiting times or a more manageable cost of living.

What have people noticed?

Rishi Sunak’s early departure from the D-Day commemorations was once again the single most recalled story from the campaign in the last few days, spontaneously mentioned by nearly 1 in 5 respondents. This was followed by the re-emergence of Nigel Farage as leader of Reform UK, followed by the revelation that Sunak did not have Sky TV as a child. This was recalled by 14% – more than mentioned manifesto launches, arguments over tax rises or the party leaders’ debates.

As we can see from our political map, most stories were most likely to have been noticed in the Labour/Lib Dem supporting left hand side of the map, suggesting that these voters are more engaged with the election than the previously Conservative-backing right hand side. The exceptions were stories about Nigel Farage and Reform UK, immigration and – perhaps somewhat archly on their part – Keir Starmer’s father having been a toolmaker.

Manifesto policies

We asked respondents whether they supported or opposed a selection of policies from each of the main parties’ manifestos (or in the case of Reform UK, policies which had been extensively trailed ahead of the party’s launch on Monday). Half the sample were told which party had proposed the policy, and half were not. In almost every case, policies were more popular (or less unpopular) when not attached to the party it came from.

Labour government – hopes and fears

We asked whether various things that voters often mention in our focus group research were likely to happen under a Labour government or not. Only just under one third said they expected more stable and competent government, lower NHS waiting times or improved public services. Just under 3 in 10 anticipated a more manageable cost of living, or more jobs, opportunity and prosperity. Fewer still thought they would see a tougher approach to crime, and only 15% expected stricter immigration controls. Fewer than half of likely Labour voters expected to see the last two on this list.

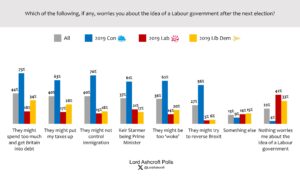

When we asked what worries – if any – they had about the idea of a Labour government, the most common answers were that it might spend too much and get Britain into more debt, put their taxes up, and fail to control immigration. Only just over 1 in 5 (and only 47% of likely Labour voters) said they had no worries about the idea of a Labour government.

Among those saying they were dissatisfied with the Conservative government and would rather have a Labour government instead, only 37% said they though Keir Starmer and Labour would do a good job governing Britain. 46% said they probably won’t do a good job but they can hardly be worse than the government we have now. Only 58% of likely Labour voters said they thought the party would do a good job; 36% said they probably be wouldn’t but could hardly be worse.

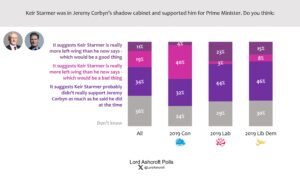

Thinking about Keir Starmer’s former support for Jeremy Corbyn, 3 in 10 voters said this suggested that Starmer was more left wing than he now says (which those leaning towards Labour were more likely to think was a good thing than a bad thing). One third thought it meant he probably didn’t support Corbyn as much as he said he did at the time.

Conservative future?

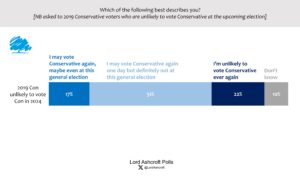

2019 Conservatives saying they were unlikely to vote Tory again on 4 July were divided as to how they wanted the election to turn out for the party. Four in ten said that if Labour were going to win, they wanted there to be enough Conservative MPs left to form a strong opposition and hold the new government to account. Fractionally more (41%) agreed that the Tories “need a huge defeat so they get the message.”

Among former Tories who put their chances of voting Conservative at this election at less than 50/100, just over half (51%) said they may vote for the party again one day but not on 4 July. Just over 1 in 5 (22%) said they were unlikely to do so ever again. 17% said they may yet be persuaded to vote Conservative at this election.

The fundamentals

Starmer’s lead over Sunak has widened from 17 to 21 points since last week, while the proportion of 2019 Tories who say Sunak would make the better PM has dropped from 45% to 39%. 2019 Tories who say they don’t know or won’t vote prefer Sunak to Starmer by 16 points (29% to 13%), down from 23 points (30% to 7%) last week. Voters currently leaning towards Reform UK chose Sunak over Starmer by 22% to 7%, with 71% saying ‘don’t know’.

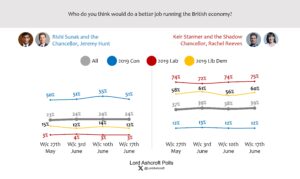

Only just over half (51%) of 2019 Conservative voters said Sunak and Jeremy Hunt would do a better job of running the economy than Starmer and Rachel Reeves. Overall, the Labour team were ahead by 15 points, with 38% saying ‘don’t know’.

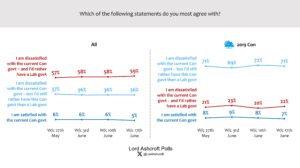

The proportion of 2019 Tories saying they were satisfied with the current government fell another point to 7%. Overall, 5% of voters said they were satisfied, 36% said they were dissatisfied but still preferred the Conservatives, and 59% said they were dissatisfied and would rather have a Labour government. Just over three quarters (76%) of 2019 Tories who say they don’t know or won’t vote said they preferred a Conservative government to a Labour one, as did 85% of 2019 Tories currently leaning towards Reform UK.

Voting decision

Among 2019 Tories, the average likelihood of voting Conservative again on 4 July was 37/100 (down from 43/100 last week), while their average likelihood of voting for Reform UK rose to 32/100. Of those who put their chances of voting for one party at 50/100 or above, we find 43% saying they are most likely to vote Labour, 18% Conservative, 18% Reform UK, 9% Liberal Democrat and 7% Green.

Overall, only 44% of voters said they had definitely decided how to vote on 4 July – the same proportion as last week. Those leaning towards Labour (66%) or Reform UK (63%) were more likely to say they had made up their minds than those leaning towards the Conservatives (58%) or the Lib Dems (50%).

The political map

Our political map shows how different issues, attributes, personalities and opinions interact with one another. Each point shows where we are most likely to find people with that characteristic or opinion; the closer the plot points are to each other the more closely related they are.

Here we see that those who say they are completely undecided how to vote, or won’t vote at all, are most likely to be found in the less prosperous, less diverse, Leave-voting bottom-right quadrant of the map, where the Conservatives under Boris Johnson picked up a good deal of support at the 2019 election. This is where we also find the biggest concentration of former Tory voters who may vote for the party again one day but not at this election, and those who say they will never do so again.

We also see the locations of peak support for various policies (put to them without party labels). Those closest to the centre are most likely to appeal across the board – such as the Lib Dem offer of 8,000 more GPs and the right to an appointment within 7 days. Those closest to the edge – such as allowing people to change sex with no need for medical reports (Lib Dem) or abandoning carbon emissions targets (Reform) have their greatest appeal among highly partisan minorities.