Yesterday we looked at what my new polling tells us about how people in the UK see the monarchy in the run-up to the coronation. Today I will explore how things look in the “Commonwealth realms” – the 14 other countries around the world where the King is the head of state.

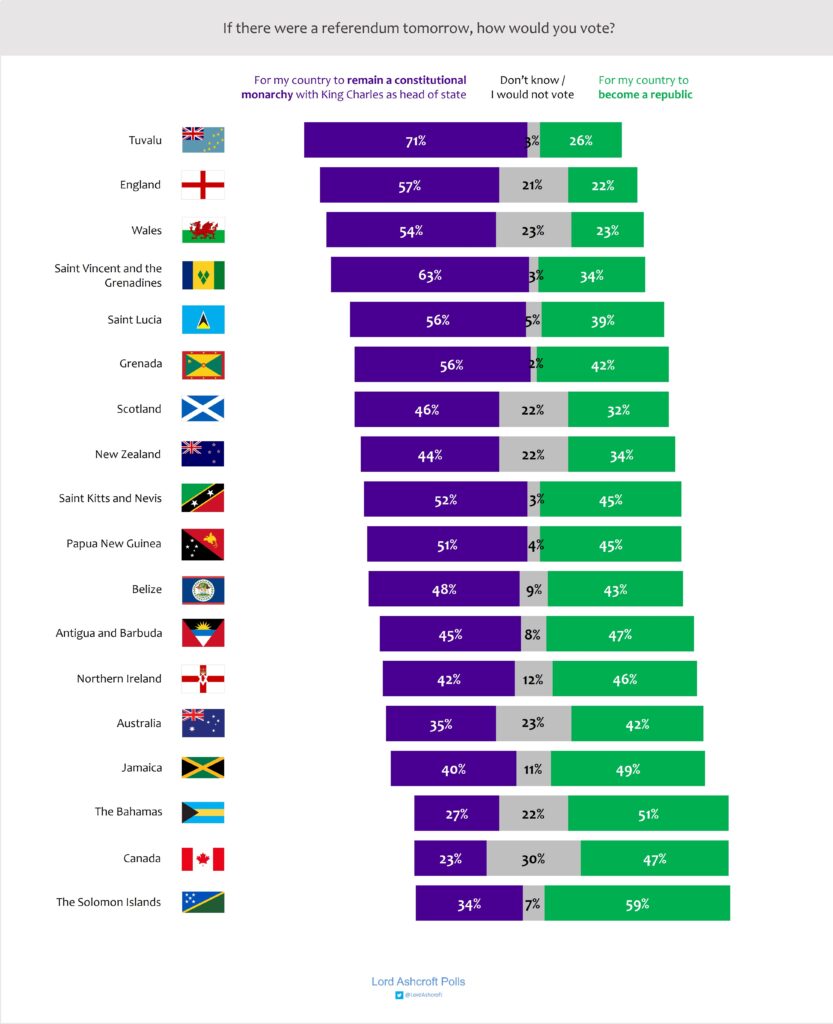

My polling found that in six of these countries, more said they would vote to become a republic in a referendum tomorrow than would choose to remain a constitutional monarchy. Margins for a republic were tight in Antigua and Barbuda (2 points), Australia (7 points) and Jamaica (9 points), but rather less so in The Bahamas, Canada (both 24 points) and the Solomon Islands (25 points).

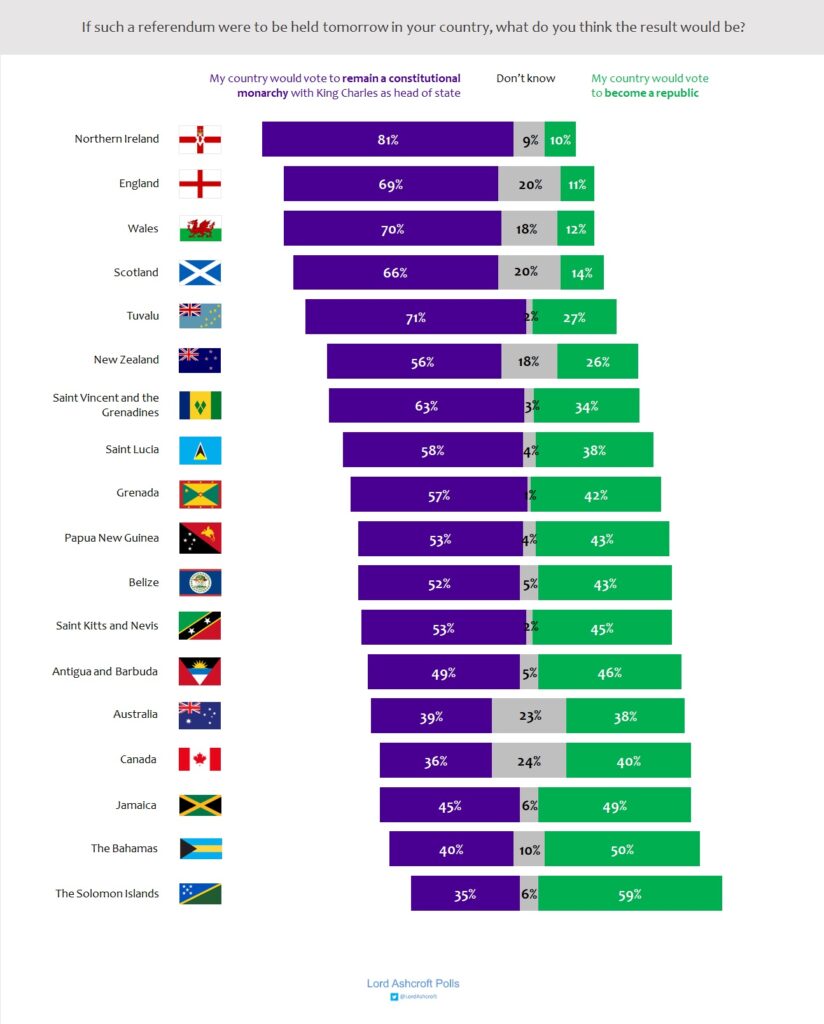

In all 15 countries, the proportion thinking a referendum would result in the status quo was higher than the proportion saying they would vote for a republic. In Antigua and – notably – Australia, more said they thought their countries would choose to keep the monarchy tomorrow than that it would vote for change, despite the results of their own “referendum” question.

In most countries, large majorities of pro-republic voters thought such a move would bring real, practical benefits. However, substantial minorities of them in Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and most of them in the Solomon Islands, said the monarchy was “wrong in principle and should be replaced whether there are practical benefits or not.” Majorities of pro-republic voters in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Jamaica agreed that having the monarchy had been good for their countries in the past, but makes no sense today.

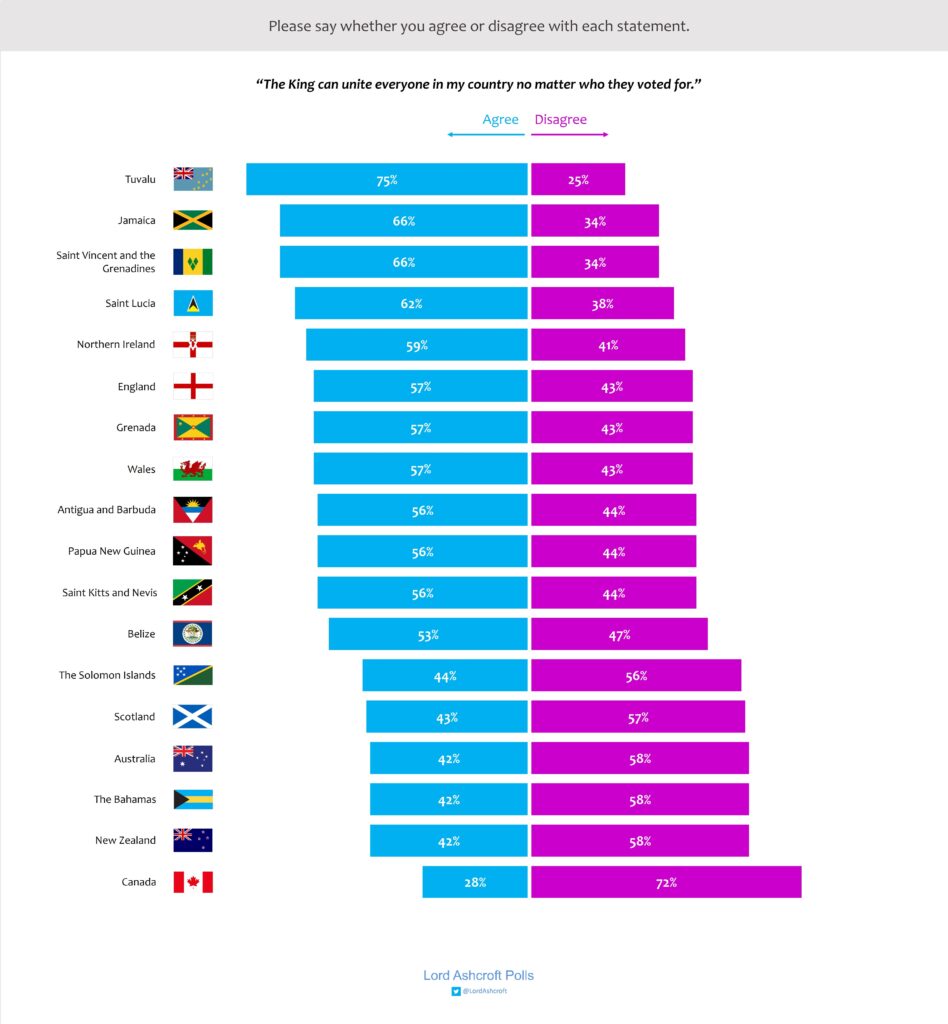

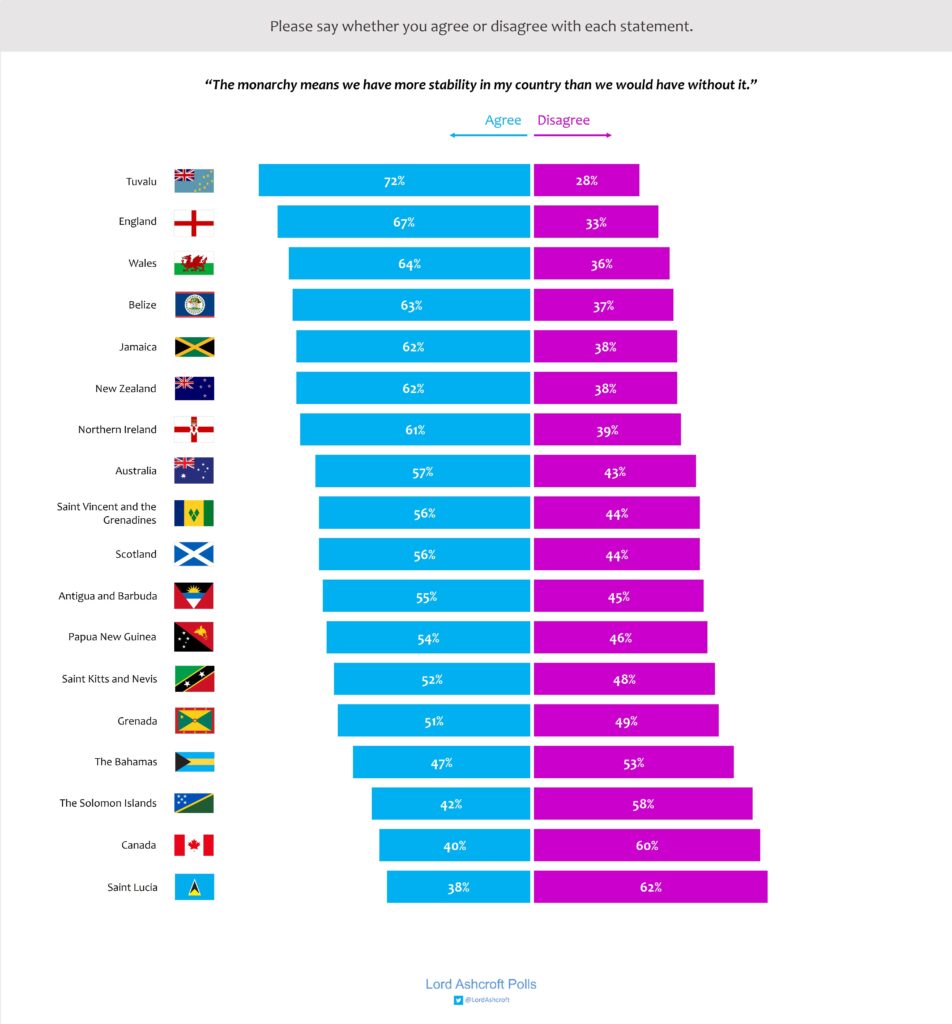

In all but five of the Commonwealth realms, people were more likely to agree than disagree that “the King can unite everyone in my country, no matter who they voted for. In all but four (The Bahamas, Canada, St Lucia and the Solomon Islands), most agreed that “we have more stability in my country than we would have without it”. Majorities in Jamaica, Antigua and Australia agreed with the statement, despite leaning towards a republic in the referendum question.

However, many felt the monarchy had little relevance in their country today. While acknowledging that the King wielded no real power, some wondered why the institution still had even a symbolic role in their nation’s affairs. This was particularly the case in our focus groups in Australia and Canada, where we also regularly heard that the monarchy was at odds with what people considered their inclusive and egalitarian national character.

In all eight countries where we conducted focus groups – Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Canada, The Bahamas, Belize and Jamaica – people said that the UK had once been an important partner in terms of culture, trade, security, and even social customs and etiquette. A looser relationship with Britain, its declining influence across the board, and growing relationships with other countries – notably the US and China – meant that ties with the old country had become relatively much less important.

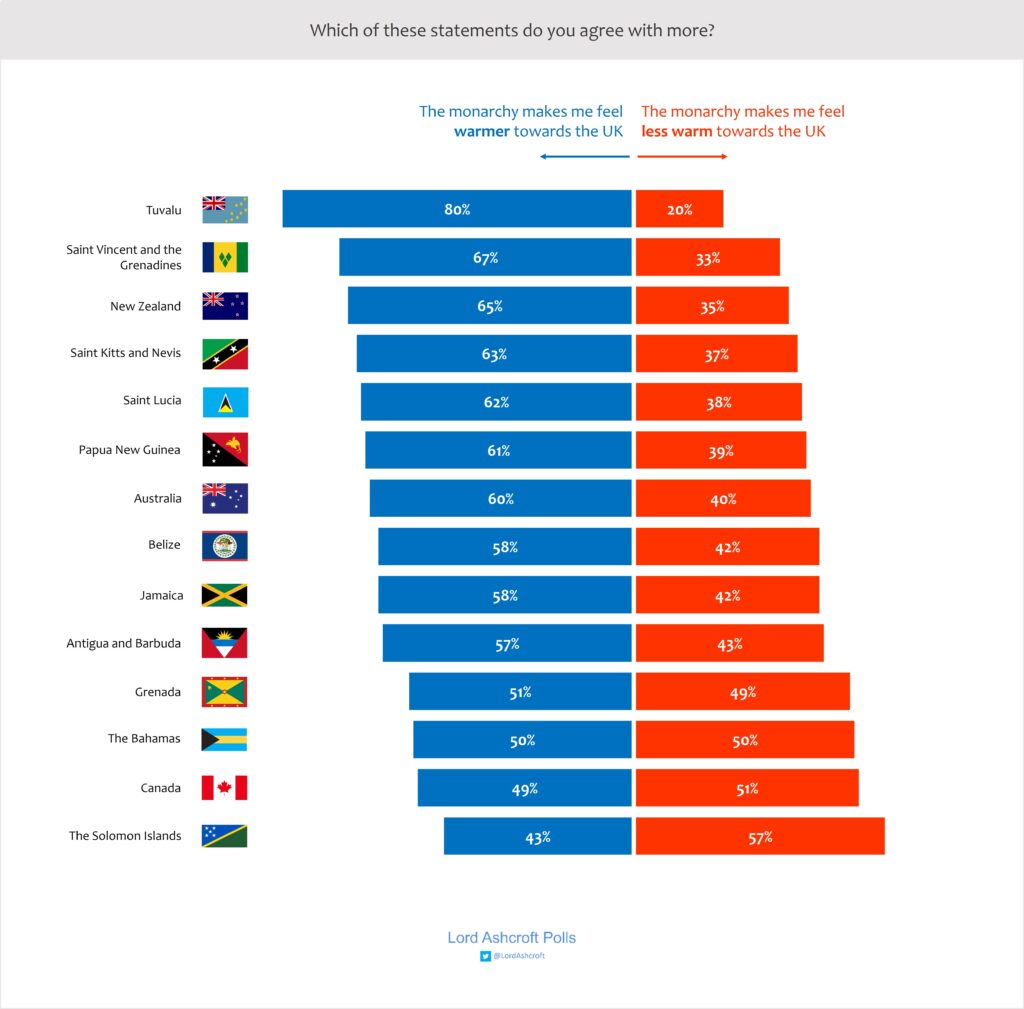

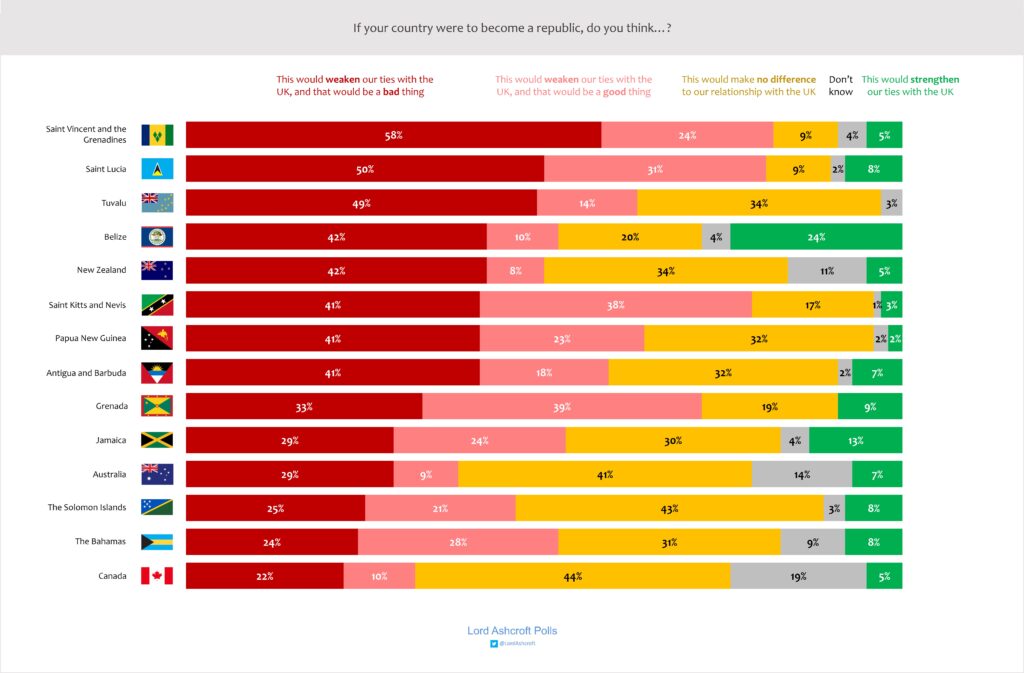

In all but two of the Commonwealth realms, most said the monarchy made them feel warmer rather than less warm towards the UK (though not by much, in some cases). Even so, many asked how they were supposed to benefit from the relationship. Less developed and emerging nations felt they received little practical or tangible support, and while some were prepared to believe Britain might be standing up for them in the corridors of international power, they had little evidence for it. Most populations were quite evenly divided as to whether or not the royal family cared about their country, but nearly two thirds in Canada, The Bahamas and the Solomon Islands thought not. In most countries, a plurality thought that leaving the Crown would weaken their ties with Britain and that this would be a bad thing, but in five of the six countries saying they would vote to become republics the prevailing view was that this would make no difference to their relationship with the UK. By clear margins, people in all 14 countries said they would want to remain part of the Commonwealth if their country became a republic.

The monarchy’s association with the history of slavery and colonialism was another inescapable factor, especially in the Caribbean. Many in Jamaica (where people said they would vote for a republic by a 9-point margin in a referendum tomorrow) said the fact that they were not only nominally ruled by their former colonial masters but needed a visa to visit the UK simply added insult to injury.

Many around the world were torn between the wish to assert their independence and end the association with historical wrongs on the one hand, and on the other, the stability and reassurance they felt the monarchy offered. People in Belize spoke of the sense of security they had felt from seeing British soldiers in their “nice big trucks”, and that even though the Army’s presence had been scaled back significantly, they felt the Crown implied a degree of protection in the face of territorial claims by neighbouring Guatemala. Many in more remote countries felt they had more influence and international standing than they would have on their own.

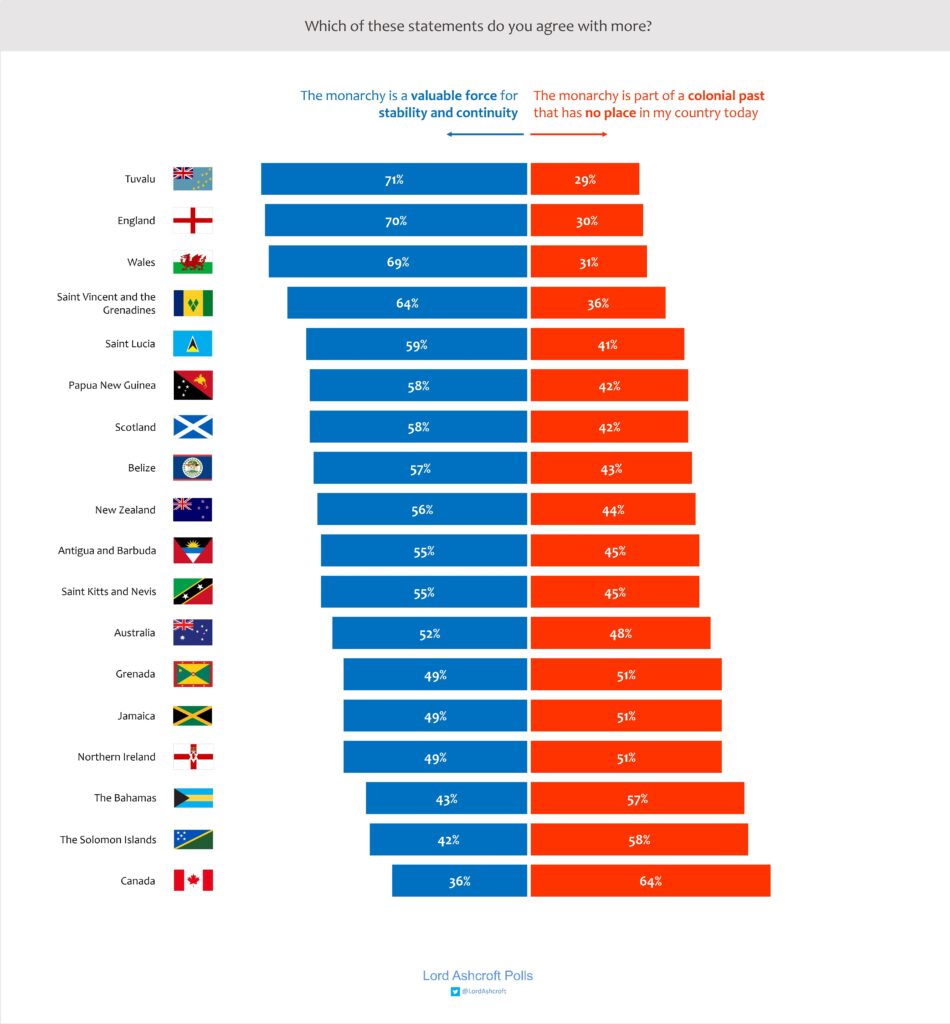

Asked to choose between two statements, people in Australia, New Zealand, Antigua, Belize, Papua New Guinea, St Kitts & Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent & The Grenadines and Tuvalu were more likely to see the monarchy as “a valuable force for stability and continuity”; those in Canada, The Bahamas, Grenada, Jamaica and the Solomon Islands were more likely to regard it as “part of a colonial past that has no place in our country today”.

On top of the tension between stability, continuity and reassurance on the one hand and independence and self-determination on the other, there is the question: what would we replace it with? Few were enamoured by the idea of a US-style executive president, but many wondered what the point would be of deposing the King only to appoint their own ceremonial president or “head ribbon cutter”.

In fact, the monarchy’s apparent remoteness from the daily lives of people who live under it is an important ingredient in helping preserve the institution. In every country leaning towards becoming a republic, large majorities – and even larger majorities among pro-republic voters – agreed that “in an ideal world we wouldn’t have the monarchy, but there are more important things for us to deal with.”