In the months leading up to Saturday’s Coronation I have polled nearly 23,000 people in the 15 countries in which King Charles III is head of state, and conducted 44 focus groups around the UK and in eight other nations around the world. Tomorrow on ConHome I will look at how the “Commonwealth realms” see their relationship with Britain and the Crown; today I will focus on how people see the institution here at home.

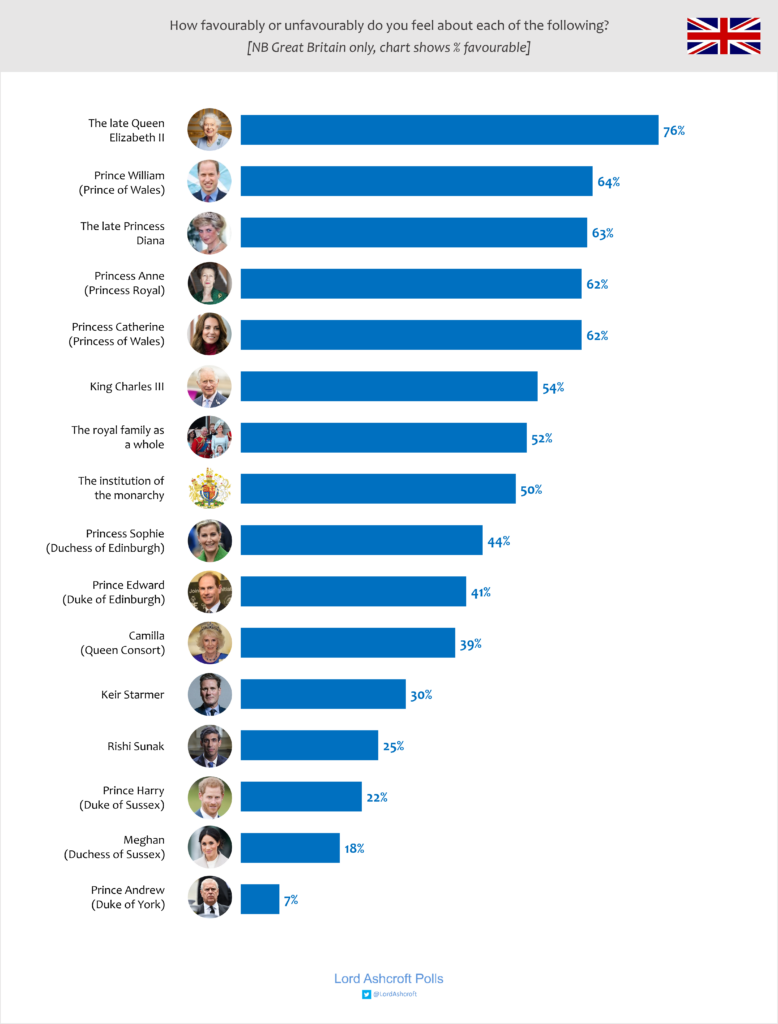

Cultivated ConHome readers may scowl at my opening with something as tabloidy as a popularity league table, but I think there are at least three things worth noting about the royal family’s favourability ratings. The first is that the King is not the most popular living royal, but rather occupies an upper-mid-table position with similar scores to the family overall and the institution itself. The Prince of Wales scores notably higher.

Second is that part from Prince Andrew and the Sussexes, all the leading royals get significantly higher scores than either Rishi Sunak or Keir Starmer. If that is predictable enough, perhaps more notable is the fact that more than two thirds (68%) agreed that “the royal family does a better job of connecting with ordinary people than most politicians”. As one of our focus group participants put it, “I think the royal family are more of the people. They meet heads of state and things, but they also meet people on the street. I don’t see Rishi doing that.”

Third is that the soap-opera element of the monarchy is essential to its continued success. Painful though the dramas and controversies must be for those living through them (for the record, 19% in Britain sided with Harry and Meghan, 40% with the rest of the family, 13% sympathised with both and 38% with neither), they underline one of the monarchy’s biggest strengths, which is that it is both a public institution and a human family that can engage people’s loyalty and interest.

Being interested in the royal family doesn’t mean we want to hear what they think, however. In my survey, pro-monarchy voters wanted royals to keep quiet on controversial public issues (by 54% to 46%), while those who would vote for a republic said they should speak out (by 55% to 45%). This was unusual; in most countries it was monarchists who wanted to hear what the royal family had to say and republicans who wanted them to keep their views to themselves. As our groups reminded us, it would be easy to wade into political controversy while talking about supposedly innocuous things. It’s one thing for the King to talk about sustainability and the environment, “but they have these great ideas and everyone else has to get on with it… He doesn’t have to put up with his blue bag, his white bag and his orange bag outside his terraced house, and only two rubbish bags every fortnight.”

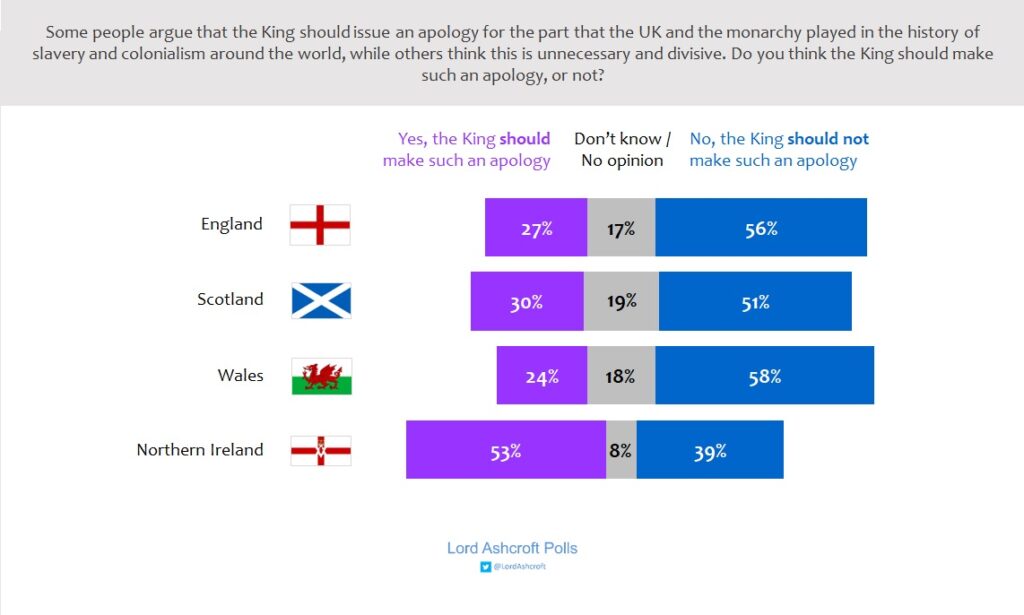

The public response to the idea of the King apologising for the part the UK and the monarchy played in the history of colonialism and slavery was another sharp reminder of the dangers here. A clear majority of people in Britain, including 74% of those who would vote to keep the monarchy, were opposed to the idea (“if we’re going back 200 years, we were one of the first countries in the world to outlaw slavery. The British Navy freed 150,000 slaves. Why should we apologise to anyone?” was typical of the robust response to the suggestion in our focus groups). Opposition was not unanimous – some feel strongly that some acknowledgment of historical wrongs should be made, especially in minority communities – but the issue is one on which it would be easy to annoy the wider public without ever satisfying activists’ demands.

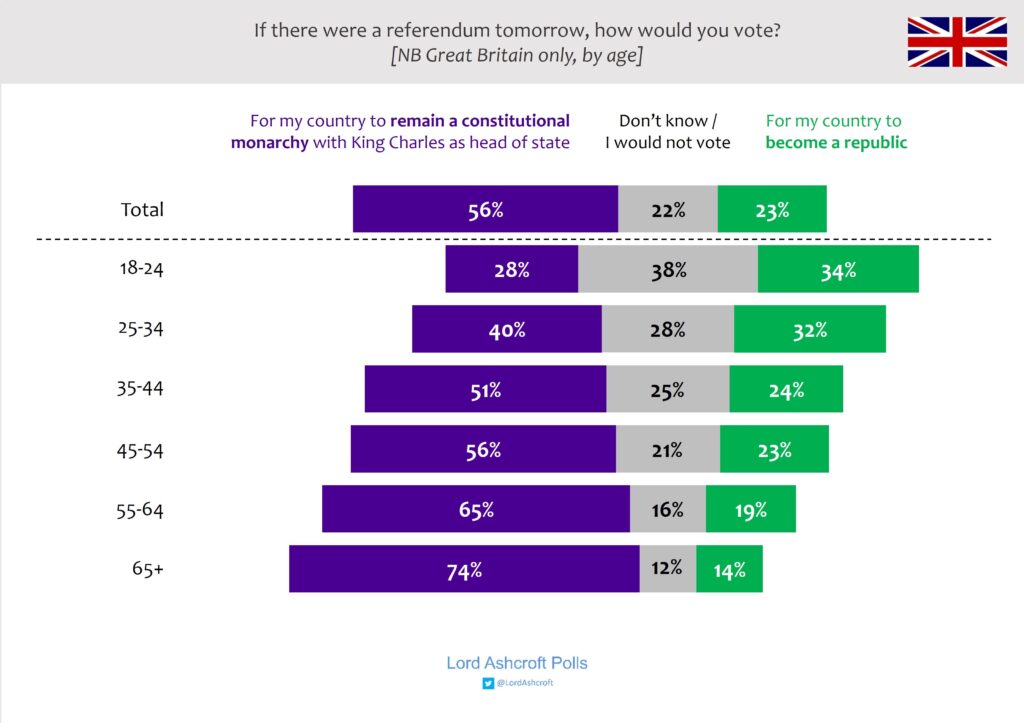

Two thirds agreed that the monarchy means we have more stability in Britain than we would have without it – a quality that people particularly valued having witnessed last autumn’s procession of prime ministers. However, only just over half (56%) agreed that the King can unite everyone in the country no matter who they voted for, and a majority of Scots and under-35s disagreed with the proposition.

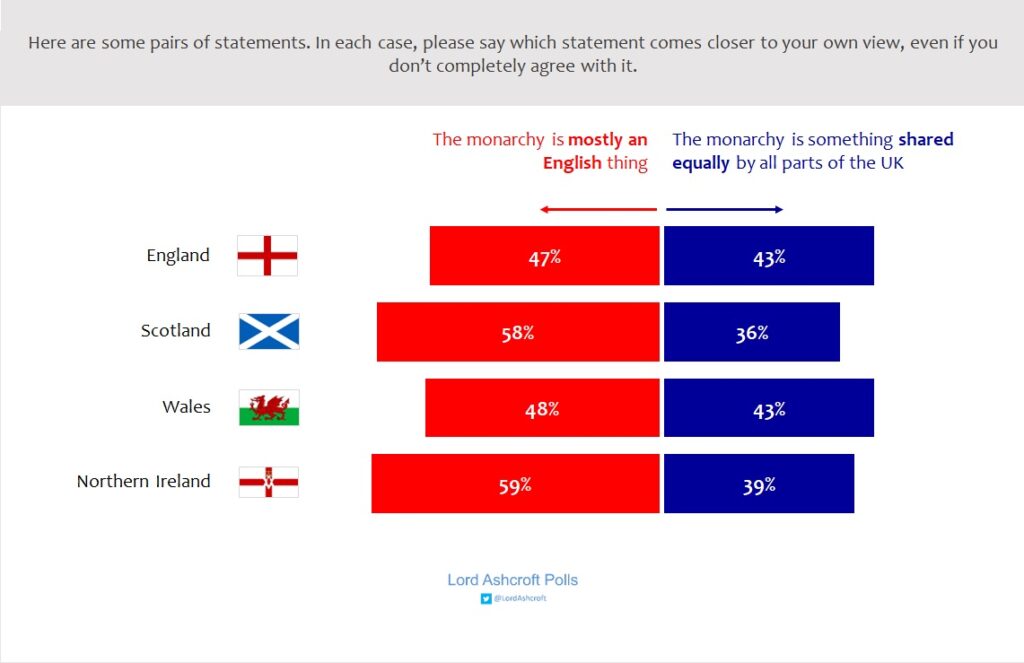

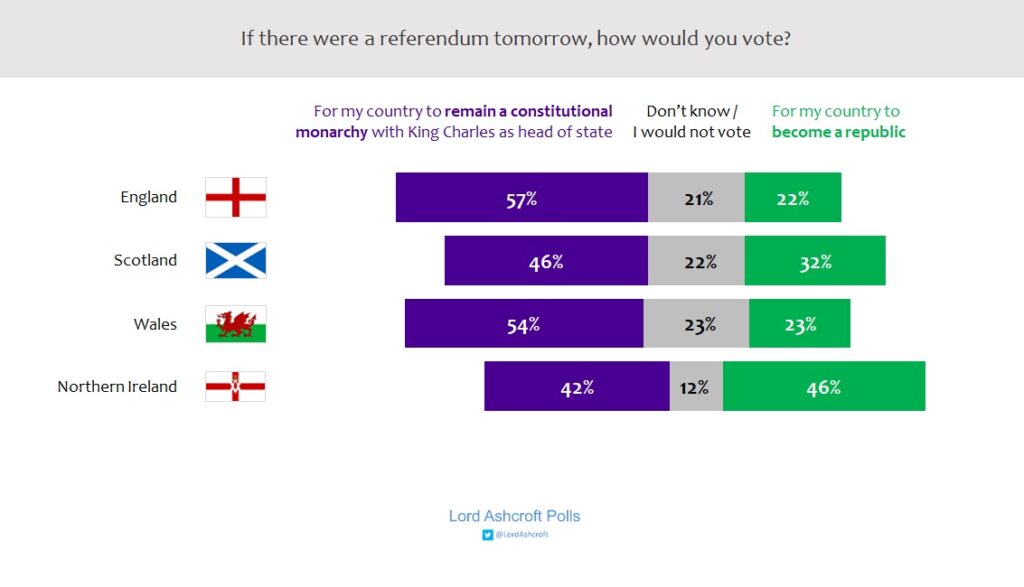

At the same time, people in England and Wales, and even more so in Scotland and Northern Ireland, were more likely to see the monarchy as “mostly an English thing” rather than something shared by all parts of the UK.

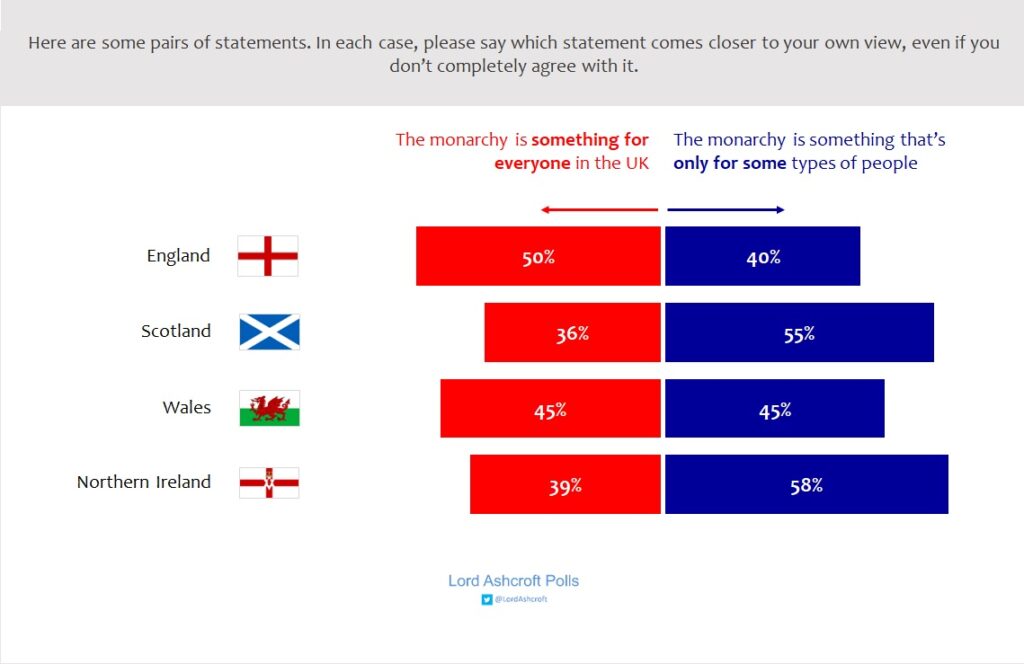

And while people in Britain as a whole were more likely to see the monarchy as “something for everyone in the UK” than something that is “only for some types of people”, majorities of 18-34s, Scots, and people from Asian, African or Caribbean backgrounds disagreed. “White English people, the history of the monarchy is their history. It’s not our history,” as one of our participants put it.

However, some took a different view, whether about Britain’s colonial history (“I’m from Nigeria which was part of the British colonial empire. They built roads and all those things. For 60 years now in Nigeria we’ve not been able to conduct a free and fair election, no roads, nothing”) or about the efforts made by the King and others to be inclusive. Many also welcomed the King’s stated intention to be “defender of faith”, upholding freedom of worship for all religions alongside his role as head of the Church of England. Indeed, we found that Muslims in particular saw the connection between church and Crown as a degree of protection in an increasingly secular society.

A clear majority said they would vote to keep the monarchy if there were a referendum tomorrow. Voters in England said they would do so by 57% to 22%, Wales by 54% to 23%, and Scotland by 46% to 32% – though Northern Ireland, with its own constitutional debate, leaned republican by 46% to 42%. 2019 Tories said they would vote to keep the monarchy by 81% to 9%, Labour voters by 42% to 38% and Lib Dems by 65% to 22% – though SNP voters said they would choose a republic by 51% to 27%.

There was also a clear pattern by age. 18-24s were more likely to say they didn’t know or wouldn’t vote than to say they would vote one way or the other, but those giving an opinion leaned towards a republic by 34% to 28%. At the other end of the scale, nearly three quarters of those aged 65 or over would vote for the status quo.

Though widespread, support for keeping the monarchy was not unconditional. More than 3 in 10 of those voting to retain it said this was because the alternative we ended up with would probably be worse, or that the process of changing would probably be too disruptive. Analysing our results we concluded that only 7% were what we have described as Committed Royalists; 32% are Mainstream Monarchists who back the institution but recognise the need to change with the times; 24% are Neutral Pragmatists, who lean towards the status quo largely because they think the alternative would be worse; 19% are Modern Republicans, who see the monarchy as divisive and worry about its colonial legacy; and the remaining 18% are Angry Abolitionists, who think the royals care little for the country and believe the institution has no place in the modern world.

In fact, three quarters in Britain, including 73% of those who would vote to keep the monarchy, agreed that “the royal family needs to modernise in order to have any chance of surviving”. Two in three, including a majority (58%) of pro-monarchy voters, agreed that “the royal family should be scaled down and its cost significantly reduced.” Many have noted with approval the King’s intentions in this regard. But while people welcomed the idea of trimming entourages and running costs, few wanted royal austerity to impinge on the pageantry (or “the bling”) that makes the institution unique.

As two thirds of people in Britain agreed, the monarchy might seem a strange system in this day and age, but it works.