My new research report, out today, is titled They Think It’s All Over. This is not (only) an attempt to find a topical link to the World Cup. It encapsulates our finding that even if Rishi Sunak and the government manage to make progress on the huge challenges facing Britain, the electoral battle they face could be even tougher.

Sunak faces problems that were familiar to three of his Downing Street predecessors. No two elections are exactly alike, but the precedents look ominous. And unlike Theresa May, Gordon Brown and John Major, Sunak faces all three of them at once.

The 2017 problem – the broken coalition

In 2015, David Cameron assembled a coalition of the willing behind his long-term economic plan to restore order to the public finances, successfully selling austerity under the promise “we’re all in this together”. Two years later Theresa May struggled to hold together this alliance (which had included many middle-class who voted Remain in 2016) and to attract enough recent Brexit supporters (many of whom were suspicious of the Tories, not least because of austerity).

In 2019, pre-partygate Boris Johnson was able to unite the factions under two themes – the imperative to finally “get Brexit done” and to keep Jeremy Corbyn out of Number Ten. In the absence of those, the remarkable Johnson coalition has collapsed.

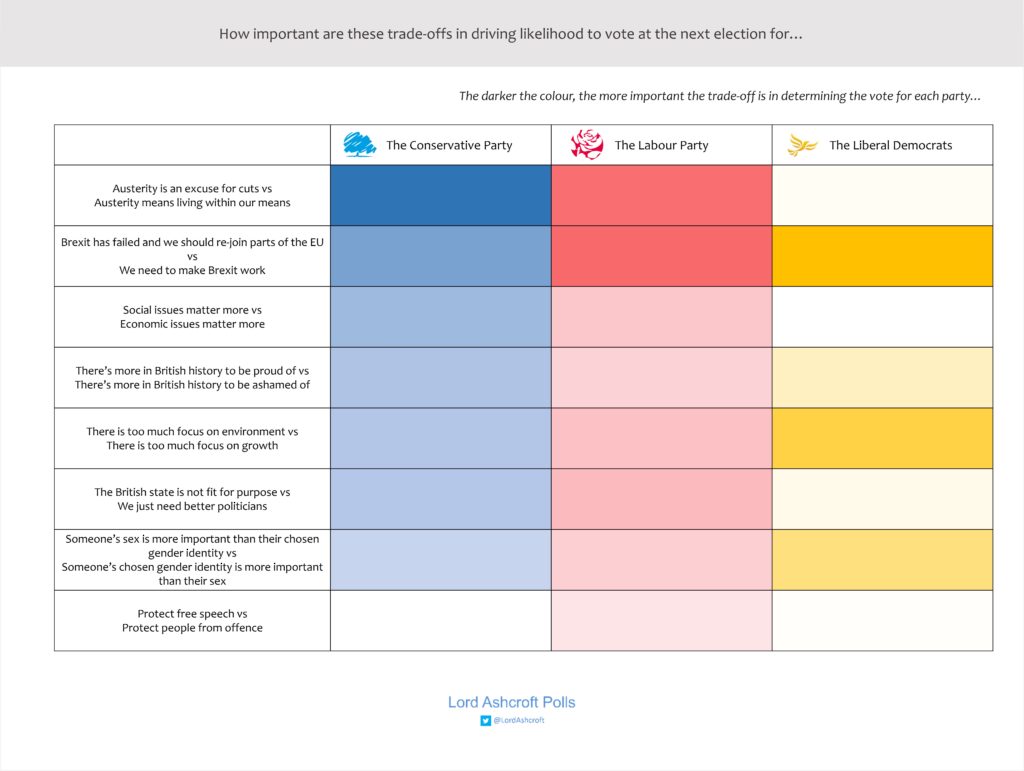

In our poll we gave our respondents pairs of opposing statements on various issues and asked which they most agreed with, then looked at how closely people’s answers on each issue were related to their likelihood to vote for each party at the next election.

People’s views on austerity – whether it is “an excuse to make the well-off richer at the expense of the less well-off” or whether it is simply “the country living within its means; without it everyone will be worse off” – were the most closely linked to their likelihood of voting Conservative or Labour. People’s views of Brexit was a stronger predictor of their support for the Lib Dems or Labour than it was for the Tories, suggesting it is a much less powerful vote-winner for the party than it was three years ago.

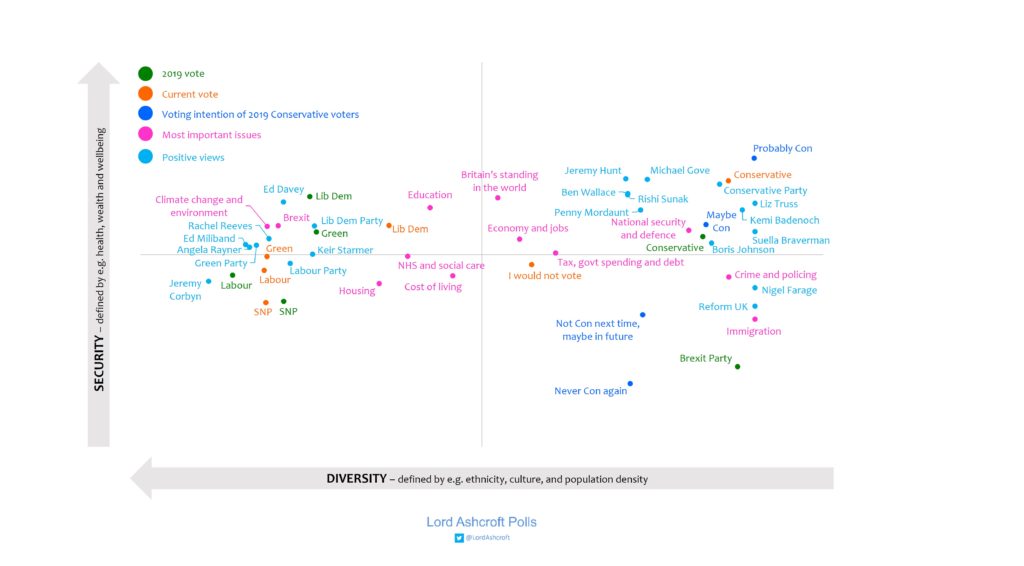

Our political map, which shows how different voters’ characteristics and opinions interact with each other, shows the effect of this.

Here we see that the centre of gravity of Conservative support has shifted from its 2019 position further into the top right quadrant of the map, where voters tend to be more secure and prosperous. Among those who voted Conservative in 2019, those most likely to do so again at the next election are to be found in the top right-hand corner; those who say they will not do so next time or will never do so again are most likely to appear in the less well-off, strongly Brexit-supporting bottom right – what was the epicentre of support for Boris Johnson in his heyday.

The 2010 problem – “don’t blame us!”

At the 2010 election, Gordon Brown argued for all he was worth that Britain’s credit crunch and subsequent recession were nothing to do with him – it was all down to the global financial crisis which he was doing his best to confront. History records the success of that endeavour. Enough voters either blamed him for racking up debt in the good years, leaving the country ill-prepared for the storm, or decided that whoever was responsible for the mess, they wanted someone else to get them out of it.

Twelve years later, the Tories are in a similar conundrum. Voters as a whole are more likely to name the government as the main cause of the problems facing Britain (37%) than either the war in Ukraine (15%) or the after-effects of covid (20%). Even a quarter of 2019 Tories say the government is most to blame.

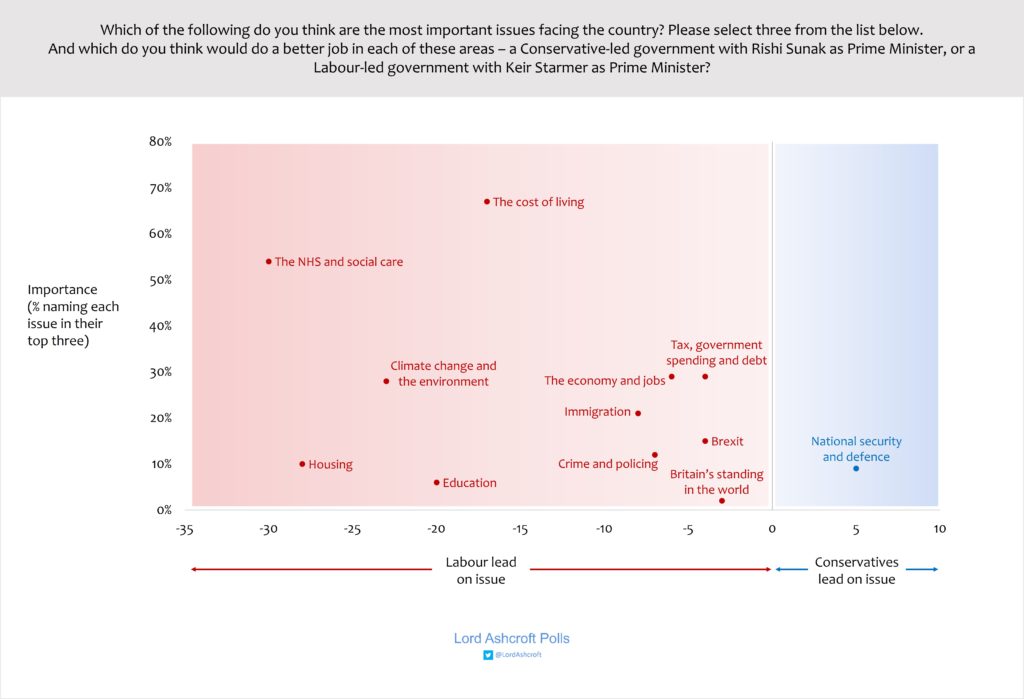

When we asked what were the most important issues facing the country and which party would do a better job dealing with them, we found Labour ahead not just on the cost of living and the NHS (far and away the most important priorities on voters’ lists) but on traditionally Conservative areas like immigration and crime.

On the top six most important issues facing the country, Labour led between 4 points (tax, government spending and debt) and 30 points (the NHS and social care). The Conservatives led on only one issue among voters as a whole: national security and defence (by 5 points).

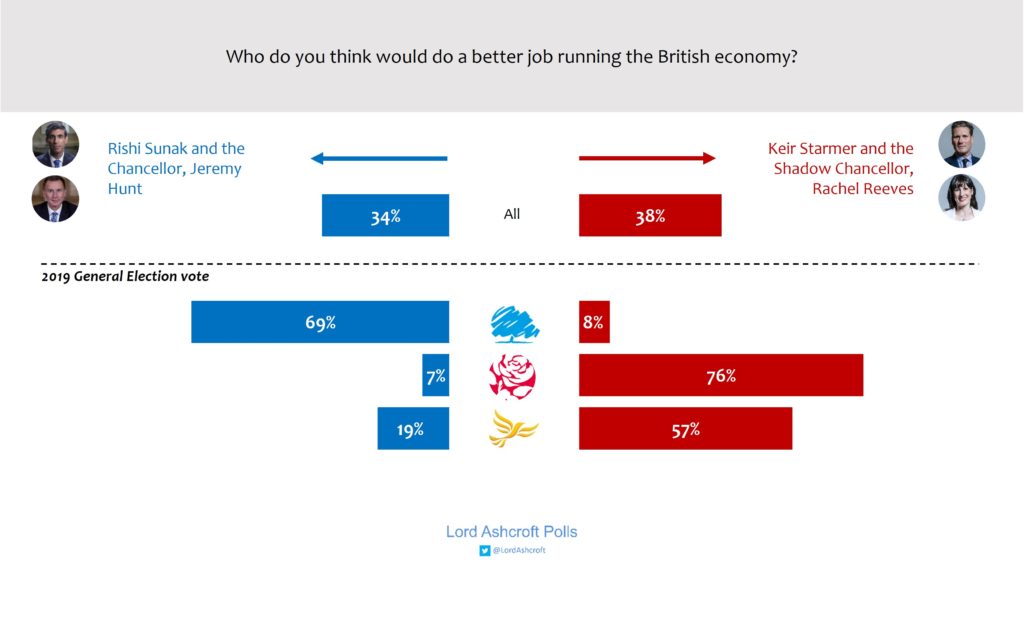

Asked directly who they thought would do a better job running the British economy, voters chose Keir Starmer and Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves over Sunak and Jeremy Hunt by 38% to 34%. Only 69% of 2019 Conservatives named Sunak and Hunt; nearly a quarter (23%) said they didn’t know who would do a better job and 8% named the Labour team.

The 1997 problem – enough already

After the recession of the early 1990s, the economy had bounced back so strongly that the Tories fought the 1997 election under the slogan “Britain is booming – don’t let Labour blow it.” The recovery was real, but this was nowhere near enough to prevent a landslide for Labour. After 18 years in office, the Conservatives looked too divided, damaged, discredited and generally worn out to continue in office.

This is the third and potentially most serious of the problems now facing Sunak and the Tories. Many of the 2019 Conservative voters said they had been relieved when he took over. If they had reservations about his ability to understand voters on modest incomes, his role in Johnson’s downfall, or the soundness (in retrospect) of some of his covid schemes, at least a sense of stability had been restored.

But the Conservative party’s brand is in a terrible state. Fewer than one in ten say the Tories are competent or share their values, and only two in a hundred say they are united.

This matters, because while voters may have seen the advent of Sunak as a return to sanity, they do not regard it as a fresh start. The all-too-familiar faces of the new cabinet underline the impression that this is a rehash, not a new beginning.

A quarter of 2019 Tories said either that they might vote for the party again in the future but could not see themselves doing so at the next election (14%), or that they could never see themselves voting Conservative again. Of the 67% who said they might vote for the party again next time, half said that “they really need to sort themselves out first.”

From our focus groups, it is clear that these wavering Tories are not expecting every problem to be fixed. They expect to see clear progress on inflation and the public finances, among other items on the government’s vast agenda. Not yet convinced, let alone enthused, by Keir Starmer, many of them may well decide to stick with Sunak.

But policy and competence are only two of the ingredients that will determine the result of the next election. In isolation, Sunak may be able to make a plausible case on both fronts. The trouble is, it won’t be in isolation, it will be in the context of all that has gone before. That is why only one in ten 2019 Tories – let alone anyone else – expect an outright Conservative victory next time round. Such a sense of inevitability could prove the hardest political challenge of all.