Polling of Conservative members, including that conducted by ConHome, has consistently put Liz Truss ahead of Rishi Sunak in the race for the leadership. My new research among wider electorate – a 10,000-sample survey together with 12 focus groups around the country – helps explain the gap. It also shows how Boris Johnson’s remarkable voting coalition sees things, and why keeping them together will be such a challenge for his successor.

As I wrote in yesterday’s Mail on Sunday, the Tories’ strategic choices are extremely limited. However much some might regret the direction the party has taken in recent years, recreating a Cameroonian coalition in time for the next election is simply not an option. The new leader’s task will be to turn out as many as possible of those who backed Johnson in 2019.

Conducting this research has brought home once again just how remarkable was the voting bloc that Johnson assembled, albeit with the considerable help of Jeremy Corbyn and parliament’s intransigent remainers. Our venues – all Tory seats – included Esher and Cheltenham, Wolverhampton and Middlesbrough, and in terms of background, occupation and ethnicity the participants – all 2019 Conservatives – were as varied as those in any research project I can remember. Welcome to modern Britain, you might say. My point is that the Conservative electorate did not always look like this.

If the size and diversity of the Johnson coalition is partly explained by Johnson and his unusual appeal, it also helps explain something about his premiership. A charitable view would be that his notorious cakeism was a response to the conflicting demands of his voters, and that if he veered about like a shopping trolley it was to try and stop any of them falling out over the edge. Another observation, shrewdly made by some in our focus groups, was that far from blighting his time at Number 10 the pandemic actually prolonged it, postponing his administration’s collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

As things turned out, Johnson was undone not by policy failures but by his own behaviour, as our research underlines.

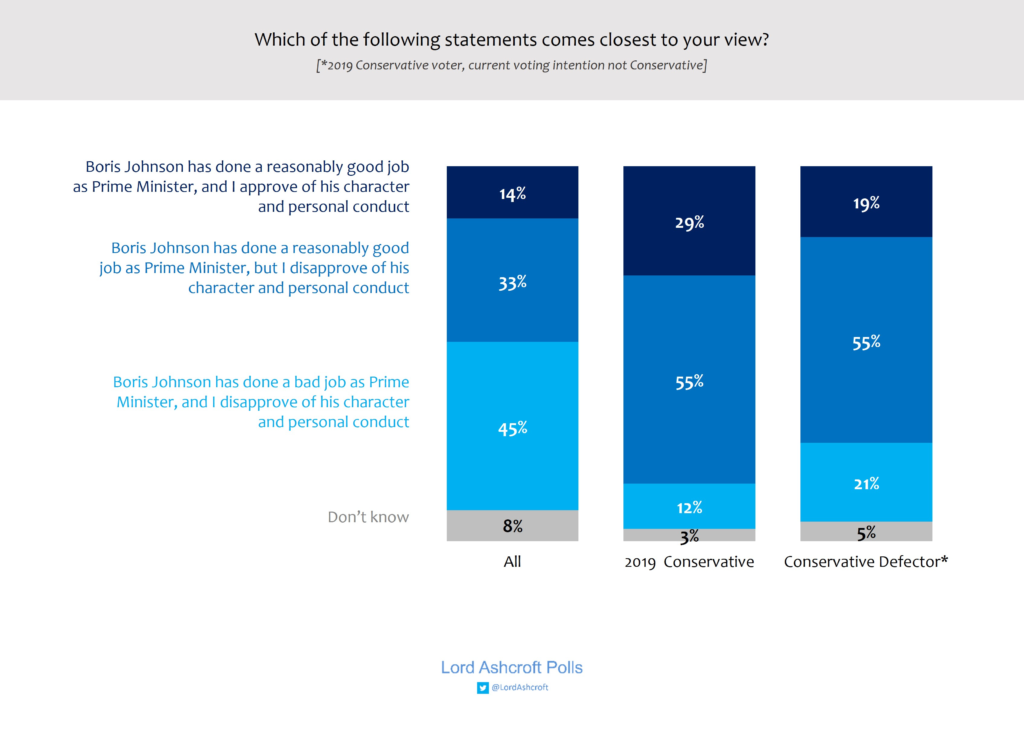

More than half of 2019 Conservatives said they thought Johnson did a reasonably good job as prime minister but that they disapproved of his character and personal conduct. Added to the 14% who approved of his performance and his conduct, that makes 84% of those who voted Tory at the last election thinking Johnson did a good job. This was echoed by our focus group participants, who praised his record on Brexit, covid and Ukraine. Even so, most agreed that he had lost their trust and had to go.

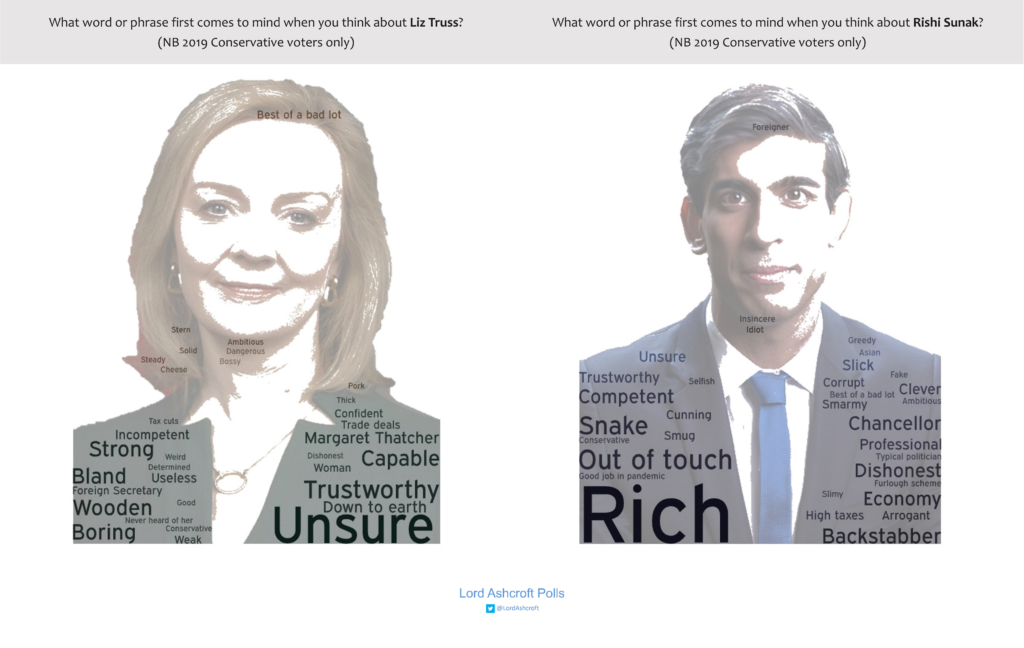

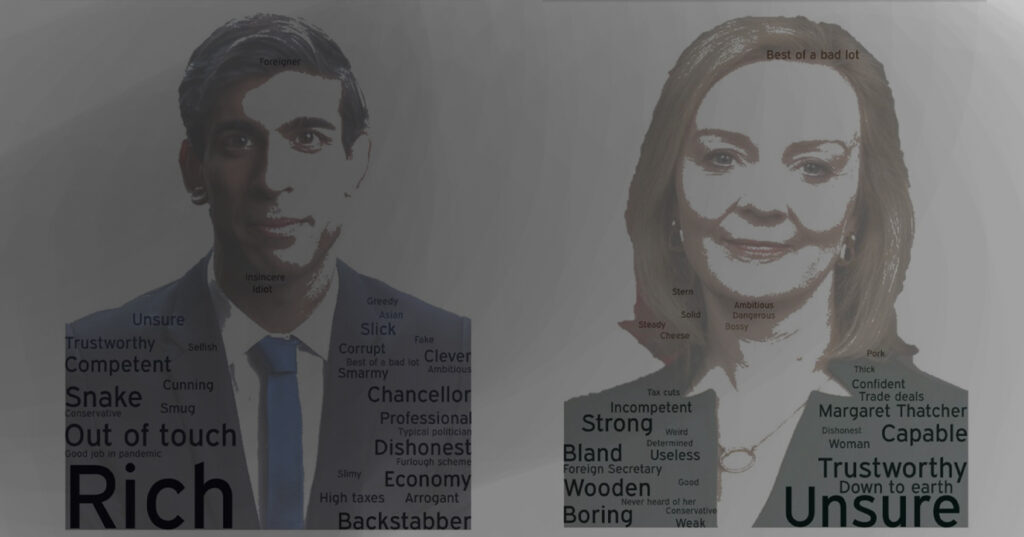

When we asked in our poll what word or phrase first came to mind when they thought about each of his potential successors, a clear picture emerged. Sunak was, first and foremost, “rich” – which would hardly matter to these (after all) Conservative voters were it not combined with the deadly “out of touch”. His family’s wealth and his wife’s tax status were always among the first things spontaneously mentioned about him in our focus groups. “Snake” and “backstabber” were references to his role in Johnson’s downfall, which many felt he had helped engineer to further his own ambitions (even if they felt the PM’s departure was appropriate, or indeed long overdue). Positive mentions usually referred to his competence and record as chancellor – which, despite praise for his swift work on furlough and allied schemes, some now felt to be mixed.

The word “unsure” for Truss reflects our finding that people knew rather less about her than about her rival, with many unable to name her current job let alone her previous posts. Even so, several had clocked her comprehensive-school background, which some thought she was playing up for all it was worth. Even so, the ploy seems to have had some effect: seeing her in action for the first time in extracts from campaign videos and TV debates, many in our groups were surprised to find themselves warming to her. Sunak seemed polished and likeable but for many somehow remote; Truss seemed more relatable and grounded. “It sounded like she meant it,” said one.

These perceptions of the candidates’ characters and backgrounds reflected, and probably influenced, how people received their contrasting approaches to the economy. Some applauded Sunak’s rejection of “comforting fairytales” and welcomed the good Tory principle that our bills should not be passed to the next generation (though some thought his subsequent tax cuts pledges undermined his commitment to it, and the apparent about-turn made the pledges themselves less convincing). But there was also a feeling that it was all very well for a man in £100 sliders to talk about fiscal restraint: people needed help now, and Truss’s promise to deal with covid debt over the longer term and ease the tax burden quickly chimed with her air of having her ear to the ground.

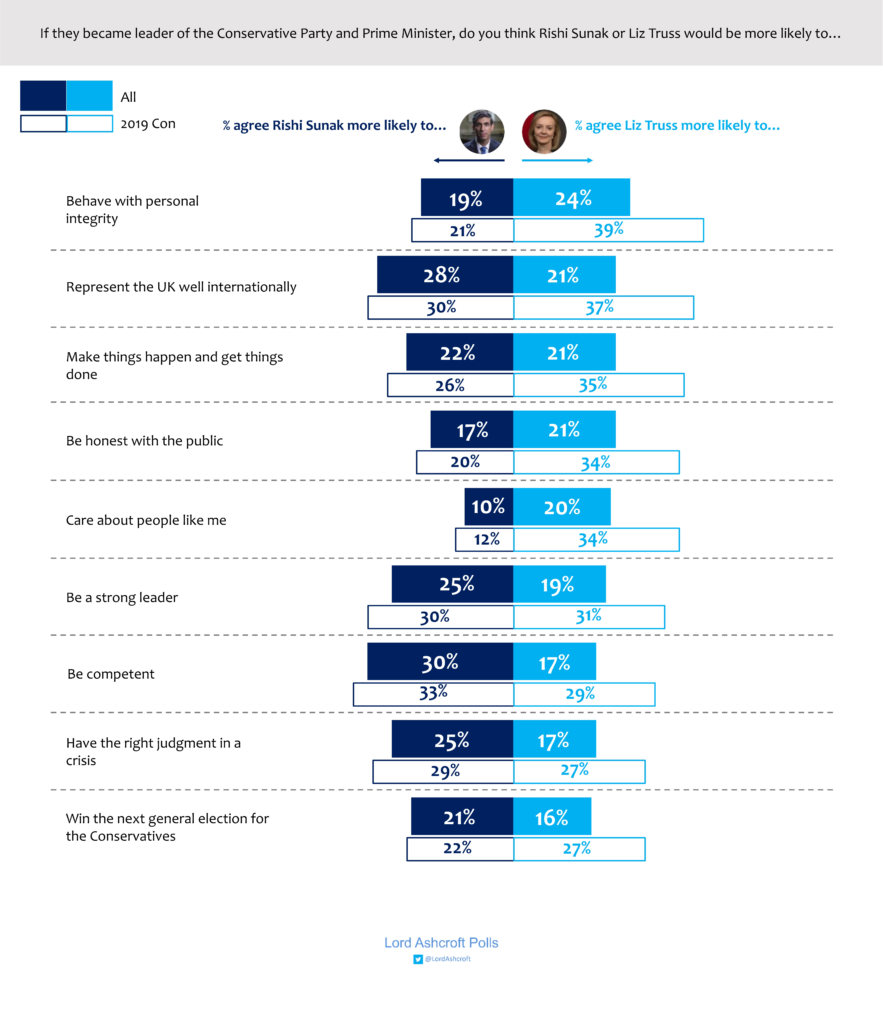

In our poll, voters as a whole said they thought Sunak was more likely to be competent, have the right judgment in a crisis, and represent the UK well internationally. By smaller margins they also thought him more likely to win a general election for the Conservatives and be a strong leader. However, they thought Truss more likely to be honest with the public, behave with personal integrity, and “care about people like me”.

Among 2019 Tories, however, Sunak led only on competence and judgment in a crisis, both marginally. Truss led in all other areas – most strikingly on being honest (by 14 points), behaving with integrity (by 18 points) and caring about “people like me” (by 22 points).

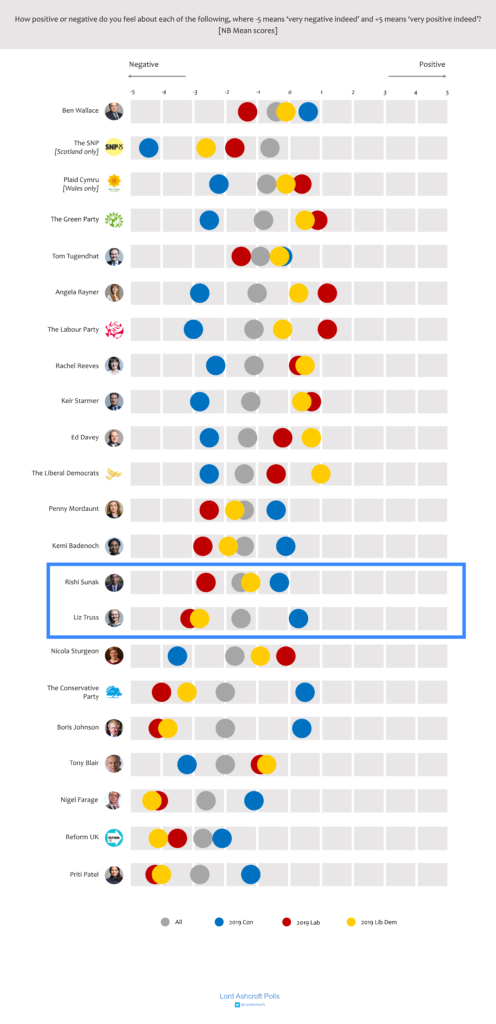

When we asked how positive or negative people felt about various politicians and parties, we found the pair with identical ratings among the electorate in general. Among 2019 Tories, Truss scored higher than Sunak but, interestingly, both were rated less positively than both Johnson and the Conservative party as a whole.

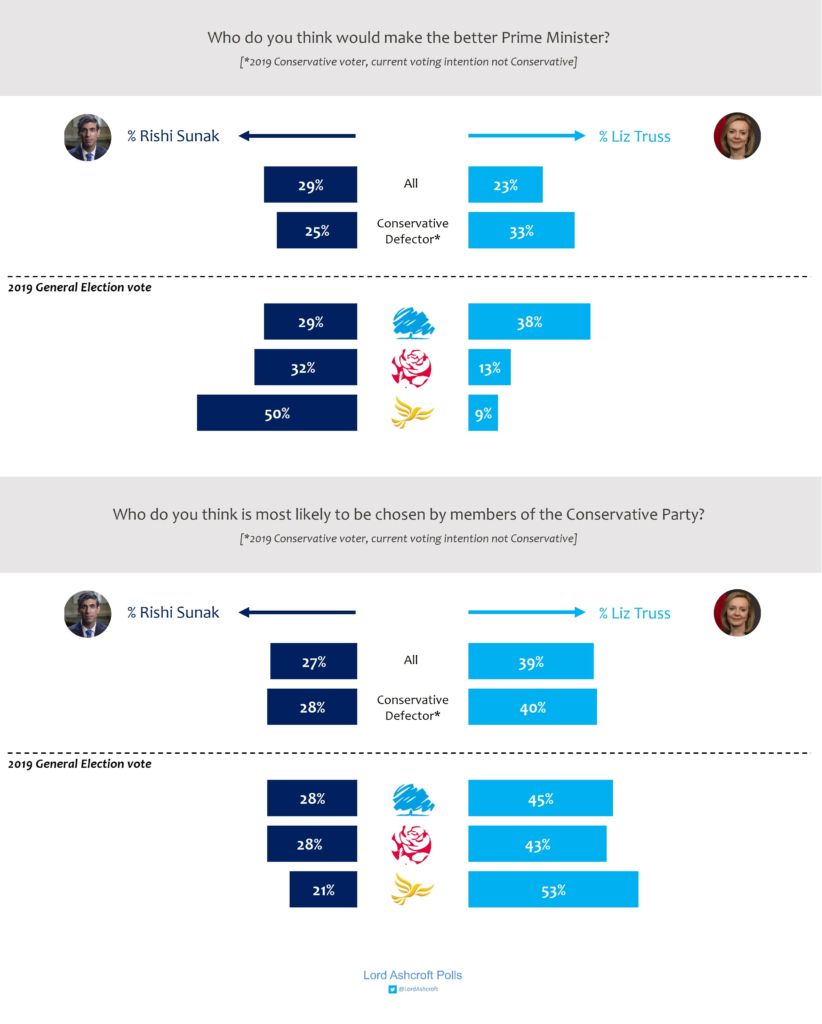

Asked who they thought would make the better prime minister, voters in general leaned towards Sunak but 2019 Tories preferred Truss – particularly those who say that, as things stand, they are not expecting to vote Conservative again next time. However, all groups thought Truss was the more likely to be elected.

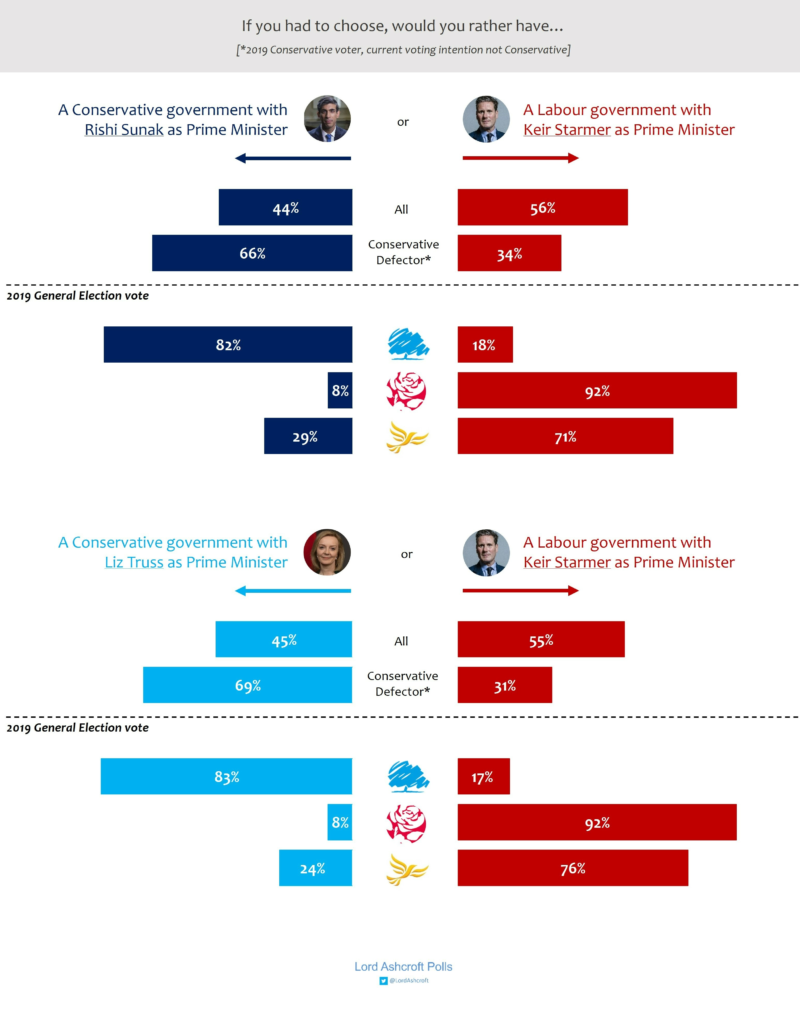

Forced to choose between a Starmer-led Labour government and the Conservatives under either prospective leader, voters as a whole chose Labour by 12 points over Sunak and by 10 points over Truss. Those who voted Conservative in 2019 but did not currently expect to do so at the next election were slightly less likely to say they would prefer a Labour government if Truss were prime minister.

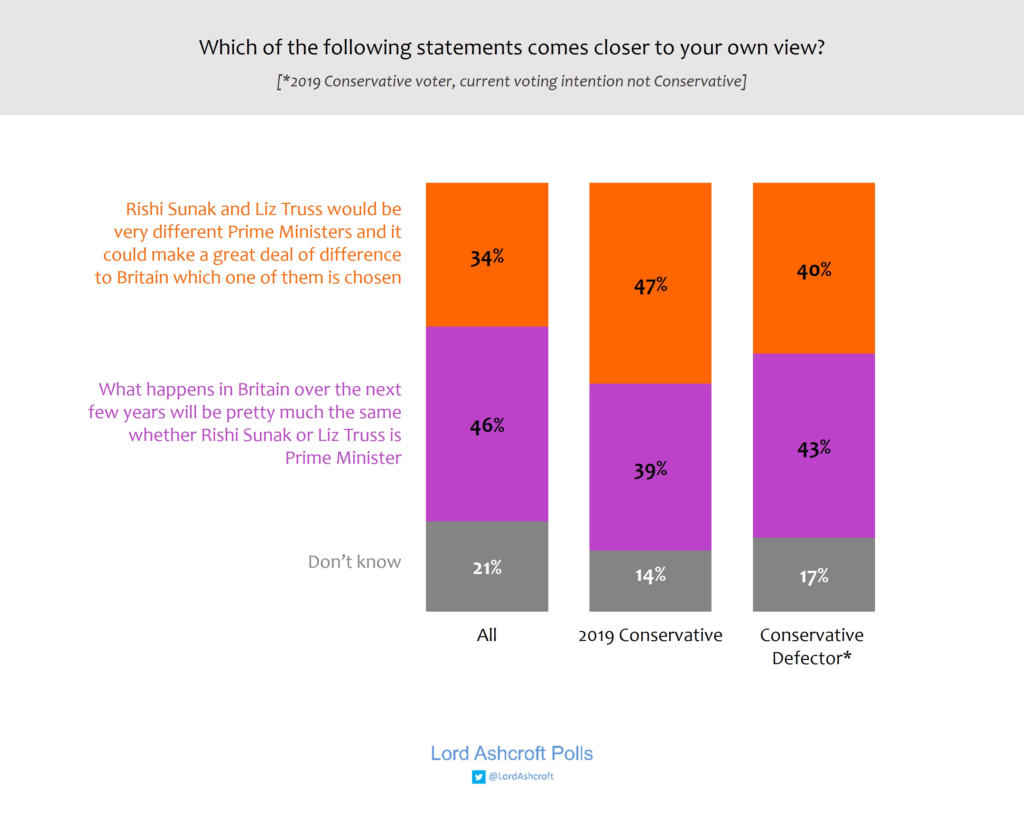

For many voters, the contest looks like a sideshow in the context of national and global events. Nearly half said that what happens in Britain over the next few years will be pretty much the same whoever is in Number 10. Tories are more likely to think the two would be very different leaders. Sunak and Truss have less than three weeks to convince members that they are the right person – and must then pull off the same trick against Keir Starmer.