Twitter wags have complained that the omnipresent message of the week – “Get Brexit done. Invest in our NHS, schools and police” – means that the conference centre is emblazoned with a list of things the Tories have not delivered. This seems unfair – parties need to look forward not back, as that Mr Blair used to say – but as I found in my most recent research, many voters are treating the “invest” part of the proposition with more than a little scepticism, even if they are pinning their hopes on the first.

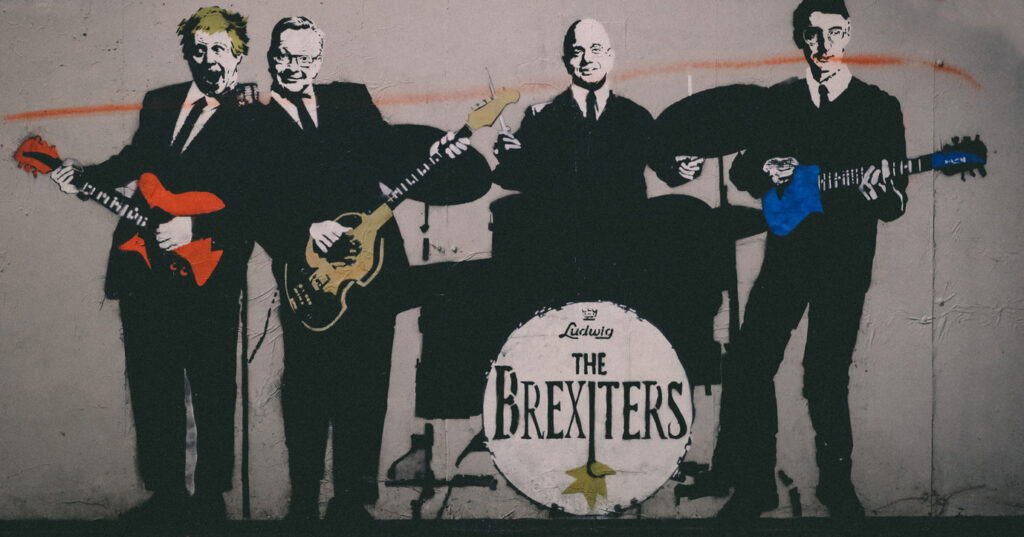

I can’t help noticing, by the way, that some of those demanding that we “get Brexit done” had the chance to do exactly that three times but voted not to do so on each occasion. What they mean is that we should “get Brexit done” on terms they find acceptable. Fine – but as so often in politics, it depends how we conjugate the verb: I’m defending an important principle, you are being obstructive, he is undermining democracy.

Another point occurs to me here. If events take a calamitous turn over the next few weeks, a government takes over that has no intention of delivering Brexit, and in ten years’ time we are still in the EU, I wonder if the “true Brexiteers”, who were too Brexity for Brexit, will reflect in their dotage on whether they should have voted to get out when they had the chance.

*

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace, in a grilling by Conservative Home’s Mark Wallace (no relation), rejected the idea that the globe was dividing into empires and that the UK had to pick one. Instead the world comprised countries who valued “the rule of law, tolerance and democracy, the rules-based system – and those who don’t.” Moreover, lavish defence spending was no guarantee of a country’s political will. Among our European allies, for example, lots of planning went on “but when it comes to who is going to go to Kosovo or the coast of West Africa, there are not many countries who actually do.” The UK would continue to face the same question: “Are we an expeditionary country, or do we just have a big budget for the sake of having a big budget? The latter view can’t be right.” In the past, ambition had not always been matched with funding. “My job is not just to sell defence to the public but to sell defence to Whitehall. What we do in Syria now stops people being blown up on the tube in London.”

The Secretary of State appeared promptly for the event despite having come straight from the funeral of Jacques Chirac in Paris. How had it been? “I had Putin in front of me and the FSB behind me. There were all sorts of people I recognised from Kremlin mugshots.”

*

Things are often a matter of perspective, as Professor Syed Kamall pointed out at a Centre for Social Justice discussion on the “forgotten few” who remain without jobs despite the UK’s record employment levels. Housing estates, for example, are often thought of as hubs of crime, but instead we should consider them hubs of enterprise: “Lots of people are starting businesses. Some of them are legal.”

Tim Martin, the founder and chairman of JD Wetherspoon – the pub chain employing 40,000 people which is responsible, he calculates, for 1/1000th of all taxes paid in the UK – is adamant on the subject of sensible regulation: “France is good at creating big jobs but it’s regulated small jobs out of the economy.” While Britain did better – licensing and environmental health rules worked well – “corporate governance is run by highly educated people in the City who think they know all about business but actually know f-all.” The recommendation that board members should serve no more than nine years means that “not one director of a UK bank was there during the last crisis. Now isn’t that reassuring?” Above all, policymakers should not look down their noses what they sometimes think of as small jobs: “Whenever I saw David Cameron and George Osborne I thought “if only you’d worked for us for a couple of years. There’s nothing like having to go into a pub in Deansgate in Manchester on a Friday night and say to six hundred people ‘OK you lot, out’.”

*

Spirited debate in the Institute of Economic Affairs ‘Think Tent’ on whether the nanny state has gone too far. “It’s no longer ‘a spoon full of sugar helps the medicine go down’, but ‘a spoon full of sugar will kill you and it’s time for the state to step in and save you from yourself, you greedy monster’,” as the IEA’s Darren Grimes put it. For Chris Snowdon, author of Killjoys: A Critique of Paternalism, the problem was that there was no logical endpoint to regulation – in America, for example, banning smoking on planes had once been considered the final frontier, but it was now illegal in some places to smoke within 25 feet of a building. The idea that such policies were evidence-based was also suspect: if minimum alcohol pricing could be set at 50p per unit, “why not 60p, why not 80p? Why not £5? It’s not evidence-based but what they think they can get away with.”

Mansfield MP Ben Bradley worried that the government too often listened to pressure groups instead of normal people. He hoped this would not be the case with the anti-meat lobby: “If you went to an estate in my constituency and said you were going to double the price of their sausages, they would be pretty grumpy about it.”

According to the commentator Tim Stanley, the ultimate goal should be “not for the state to tell people how to run their lives but that people are educated and culturally enriched enough to run their own lives.” For him, “the good life is steak and chips, a glass of wine and a Marlboro Light. Sometimes the government just needs to say to the lobbyists: ‘no’.” On the other hand, the tax on supermarket plastic bags meant that “people are using wicker baskets again like fifty years ago, which is marvellous.”