As MPs prepared to begin the process of narrowing the field of leadership contenders this week, I conducted focus groups in two rather different Conservative seats – leafy Putney and leave-y Thurrock – to see what wavering Tory voters made of the race.

Just as there were mixed views about Theresa May’s tenure in Downing Street – “she was in an impossible position and had no loyalty from her party;” “it was her choice to take that position and she made mistakes;” “history will be kind to her because she stayed strong in an absolute shitstorm” – there were varying degrees of optimism as to whether her successor would be able to get out of the Brexit rut. Few thought a new Prime Minister would be able to persuade more MPs to back a version of the Withdrawal Agreement (“the problem wasn’t personal, the problem was the deal”), but most leave voters and even some remainers thought there might now be scope for progress with the EU: “They say they’re not going to negotiate any more so you get the impression there won’t be a chance for a new leader to get a different deal, but somehow I think there will be. A new person will be able to have a new discussion;” “Someone with a will to do it. You got the impression that Theresa May was dragging her feet at times;” “You’ve got to have faith, you’ve got to give them a chance. The way they conduct themselves initially is the key thing;” “There’s a lot of room for improvement… You need someone with a bit of personality, a bit of persona.”

What, if anything, had people noticed about the contest to find such this individual? “All I’ve heard is someone sniffing cocaine. I can’t think of his name.” Most participants (and most could in fact remember the name in question) thought this didn’t matter: “Everyone’s got a past;” “It entices me to like them more because they’re a bit more open-minded. More honest as well, more in touch with the real world;” “Before that came out, I thought he sounded like an alright candidate. He still does.” There could even be public health benefits from the revelation: “MPs are making drugs uncool.” But the minority view was also strongly held: “It’s serious Class A drugs. I think it does matter. It wasn’t that he tried it once, it was on a regular basis. In his line of profession he can’t be doing things like that;” “You would want our leaders to be humble, honourable – are they the characteristics of a leader who’s a smackhead?”

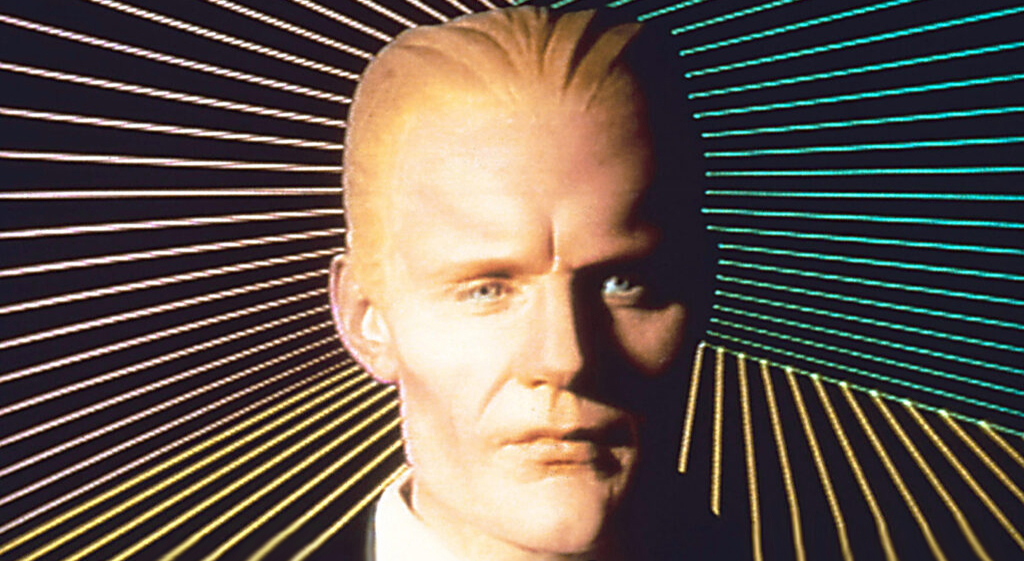

If this latest story was not a reason to doubt Michael Gove’s suitability for Number Ten, there were others. The strikingly widespread recollection that he “stitched up Boris” in 2016 had given rise to doubts as to whether he could be trusted: “He’ll just change his mind. He’s not consistent, he’s a snake.” For the teachers and relatives of teachers in the groups, “what he did with education means he shouldn’t be anywhere near Prime Minister. I’d go and live abroad.” While some did think he came across as competent and direct, seeing his campaign video reminded others of their doubts: “I feel like he’s old Britain, like the old guard;” “I can’t take him seriously. His face is a little bit funny… He looks like a male version of Katie Hopkins;” “I just don’t buy the guy. Slick but insincere.” Still, “in the Conservative Party that will sell,” and “anything to keep Corbyn out, I say.”

Most had not heard of Rory Stewart until he entered the race. Our participants’ overall reaction was gently positive. “He was talking about traveling across, was it Africa or somewhere, with no shoes on. He had quite an interesting youth;” “He looks after prisons, doesn’t he? He’s trying to do some good work there;” “He wants to fulfil the people’s choice to leave. He sees it as a bit of a tricky one but he’s going to make it happen;” “I think he’s quite trustworthy actually. The problem is, he’s another Old Etonian, and do we need another one of those?” The two words most frequently uttered in response to his campaign video were “sweet” and “interesting” – but while many liked what he had to say, few could see him in the top job: “It’s very romantic, isn’t it;” “He’s an interesting bloke but he doesn’t look the part, unfortunately;” “Is he for real? Where does he come from? It sounds like he wrote a song;” “Sweet, but do we want him running the country?” “Not a strong figurehead who’s going to lead us through. Could be a good number two;” “If you whacked him with a cold salmon he’d fall over;” “I look at him and I can’t take him serious. He’s making some fair points but I wouldn’t want him to be the face of the country.”

Our groups were also unpersuaded that Matt Hancock currently had what it took to be PM. At least half did not recognise his picture (“Is that Mogg Whatsisname?” “He won’t be in the final two so I haven’t paid much attention;” “Is he called Nigel?”) Many felt that at his campaign launch he was aping the last Prime Minister but three, not altogether successfully. “He reminded me of Tony Blair, in a dated way. I think politics has moved on from there;” “He’s still learning his trade;” “He’s one of the more genuine ones, but he needs another ten years;” “Looks pretty but a bit unconvincing;” “If you put him up against 27 European politicians they would walk all over him.”

Few knew anything about Dominic Raab other than that he was prepared to leave the EU with no deal. Those who knew he had served as Brexit Secretary did not necessarily see this as a point in his favour: “He was the Brexit negotiator. So he did a good job, didn’t he?”; “didn’t Theresa May sack him?” A few also remembered “a big gaffe. I think he’s the one who didn’t realise there is a bit of water between England and France. Something ridiculous like that.” Even so, some thought that when he declared his candidacy he came across as “honest and real,” “direct”, and a “strong character” who “gets to the point” – but they knew nothing of his background wondered what was on his agenda beyond Brexit.

Many in the groups already considered Sajid Javid to be a competent politician and a plausible candidate: “If he says he’s going to do something he seems to follow it through when the others are full of hot air.” A few had picked up that “his dad was a bus driver” and that he “was the only one who wasn’t invited to lunch when Trump came.” If people’s initial reaction was characterised by respect rather than warmth, some said after seeing his campaign film that there was room for him to make an impression: “I quite like him. He was one of the first people who said ‘the reason I went into politics…’;” “There were not loads of promises, just what his drive was. He was confident and he didn’t go off the rails about Lisa in Lewisham.”

Jeremy Hunt was as well recognised as the Home Secretary, and all four groups had clocked his encounter with Victoria Derbyshire (“A lady pronounced his name wrong. I think she did it on purpose. She wasn’t that embarrassed.”) Knowledge about his background was rather hit and miss: “He’s the transport minister, isn’t he?” “He’s married to a Chinese lady;” “He doesn’t want to leave without a deal;” “I think he’s remain;” “Didn’t he leave some documents on a train?” His campaign film impressed many: “He was saying he started off as an entrepreneur and was talking about the things he had to have, confidence, negotiating skills, things you actually need as a leader, and he’s taking them into politics. I think he’s the best candidate we’ve got;” “I might put a bet on him. If it comes down to Boris and him I think it will be very close;” “There’s a fair bit of honesty there. He’s confident and enthusiastic. I think people would listen to him.” Even so, a few wondered whether he had the X-factor: “I like some of the things he said and as a minister backing up the PM he might be good, but I’m not sure he’s a born leader.”

Boris Johnson was, of course, by far the best known of the candidates on offer and the one to provoke both the strongest reactions and the most formed. He was certainly the biggest figure in the race, and had something indefinable that others did not: “He’s got a likeability about him. He gets under people’s skin and gets them to like him;” “He was Mayor of London for two terms which is hard because it’s quite left wing in London, and we had the Olympics. He’s a philanderer and he has certain moral issues but nobody’s perfect. He’s got a track record of getting things done;” “He’s passionate and expressive. I like his message;” “I like Boris. He always talks to the people, he’s a people person, he’s there riding the bike, he’s just involved;” “His single-mindedness. He could be the person to move Brexit forward;” “They need a presence, and most of them don’t have that.” At the same time, some said their opinion of him had deteriorated over the years: “I was a great fan when he was Mayor, but he hasn’t been supportive of the last two Prime Ministers and he’s lost a lot of Brownie points. It will be interesting to see how he could bring the party back together because he’s been a disruptive influence.” But those who felt negatively also did so more strongly than they did about any other candidate – and remember these were all 2017 Tory voters: “He’s a compulsive liar;” “He had two articles written, one leave, one remain;” “A cheater;” “Round the bend;” “I don’t trust him;” “He’s great at telling people what they want to hear, Boris, so he’ll just go wherever. That’s a bit of a danger;” “I don’t think he’s normal at all, I think he’s very peculiar;” “A devious individual and he’s doing everything to attract attention to himself;” “He’s incredibly personable but he doesn’t care about genuine people, I don’t think.”

For most in our groups the strongest candidates were Boris, Jeremy Hunt and Sajid Javid, though Rory Stewart had also stuck in several people’s minds. But one consistent theme was that people were interested first and foremost in the candidates’ apparent character and competence – they had simply given up listening to policies or plans, whether on Brexit or anything else: “They’ll say one thing to your face and then get in the car and say ‘ha, they bought that one, didn’t they’;” “Whenever I read about them, the underlying thing that I just can’t seem to get past is that they’ll do whatever it takes just to be leader and then change their mind;” “I’ve heard it and heard it and heard it and now I’m exhausted with listening to all their twaddle.”

For some of these voters, the identity of the next leader made little difference: “Jeremy Corbyn would be disastrous but I’m more worried about John McDonnell. They’re a double-act, and it’s not a comedy act either.” But worryingly for the Conservative Party, some of these 2017 Tories thought a Corbyn government so unlikely that they could afford to be choosy: “I don’t think Corbyn will win, so for me it’s between the Conservatives the Liberals, and I’m losing faith with the Conservative Party;” “Brexit is going to be done and it depends what happens afterwards. Not all of them are saying much about that;” “I might vote for the Brexit Party if it isn’t done right;” “If they say it’s going to take another three years, I’ll say ‘on your horse’;” “They have to unite again;” “They need to deliver Brexit and get on with running the country. For three years they haven’t done anything with the country and it’s going to crap.”