Divided though we are, one thing everyone in the country seems to agree on is that they are sick to the back teeth of our political class. Individual politicians still sometimes inspire support or admiration – Theresa May not least among them, it should be said. But depending on your point of view, politicians have either failed to deliver on a clear and unambiguous promise to the voters, or spent two years indulging their own obsessions at the expense of things that really matter, or some combination of the two. Whatever the outcome of the current debacle, one casualty could be the parties as we know them today, with The Independent Group – in its new guise as Change UK – in the vanguard of a new political order.

Bring it on, many will think. But beyond general exasperation, what is the real nature of people’s discontent? Where is the real space for a new movement, and what could this new world look like? My latest research points to some answers.

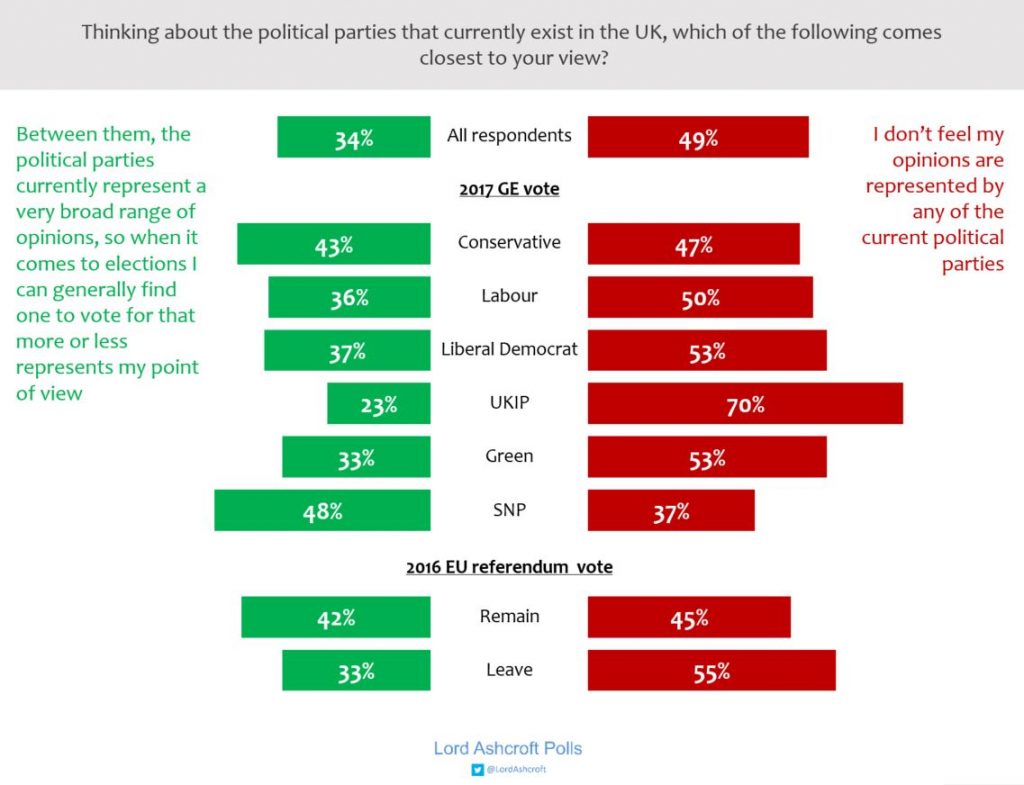

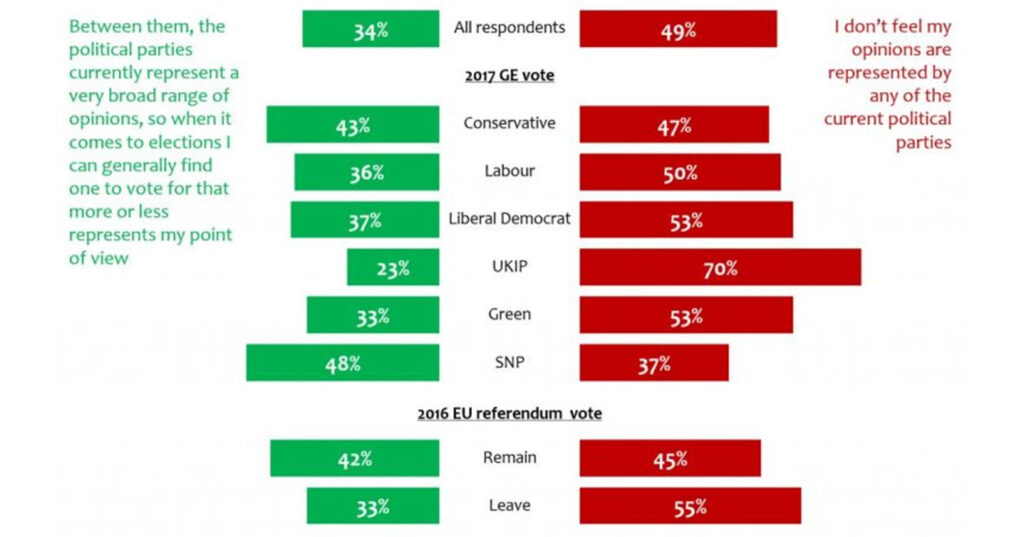

It will not come as a surprise that half of all voters say they do not feel represented by any of the current parties. That includes half of 2017 Tory and Labour voters, and seven in ten of those who voted for UKIP. Despite the vocal complaints from many remainers that Labour has not come out against Brexit, it is Leave voters who are more likely to feel that none of the parties really stands up for them.

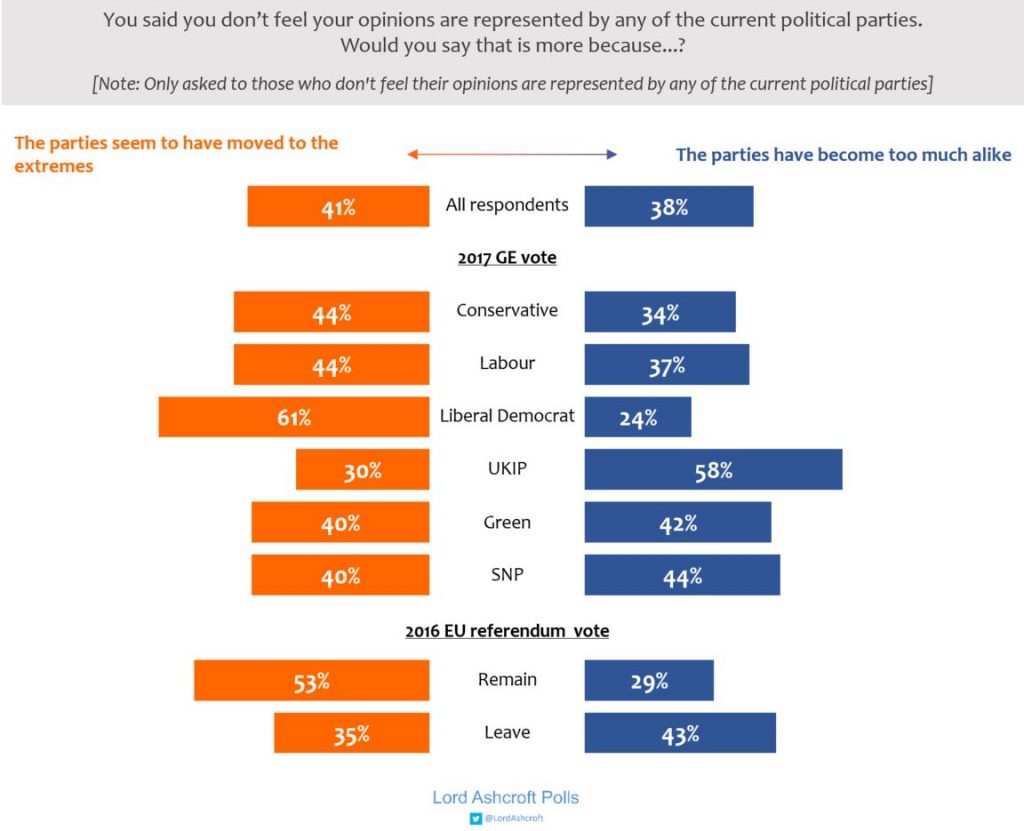

By the same token, it has become a familiar refrain that the two parties have moved to the extremes, with the Conservatives held to ransom by Brexit purists and Labour dominated by the Corbynista left. But I found almost as many of those who feel unrepresented saying the real problem was that the parties had become too much alike. Not necessarily in terms of policy, but in other important ways, as we regularly heard in my focus groups: “Politics is now filled with people who went to private school, did politics at university, and at 21 or 22 get a job up in the gilded palace, and they’ve never bought a pint of milk or had a mortgage in their life… They’re completely out of touch with what goes on in reality.” And also, crucially, in the way they behave, especially in saying one thing and doing another. If there was never a golden age of parties faithfully keeping their promises, the failure to deliver Brexit on time, if at all, marked a new low: “I didn’t think much of them but when we had the referendum, I thought fair enough, they’re giving us the chance to have our say. But now they’re going back on it;” “The trouble is, every time you give these politicians a job, the screw it up. They lie to your face to get the job and then make a mess of it.”

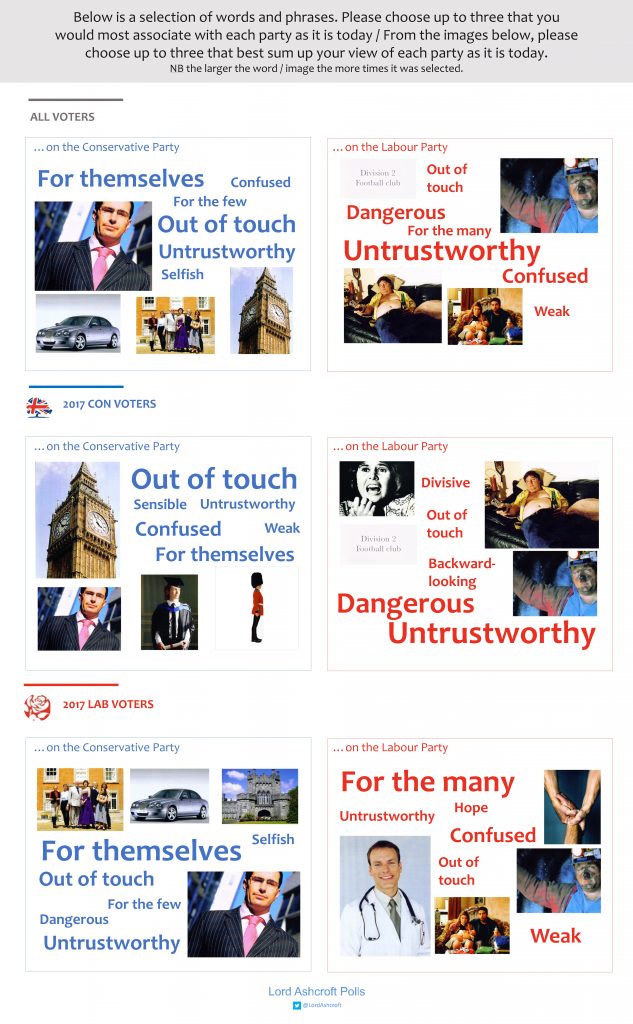

This hearty disdain was echoed when we asked participants in our 8,000-sample survey to choose from a wide selection of words and images those which they most associated with the two main parties. This is a technique we used when I was in charge of the Tories’ internal polling as Deputy Chairman before 2010, and the results were similar – except that things have perhaps got rather worse.

As it did a decade ago, the Conservatives’ selection included a posh family outside a big house, together with other images signalling privilege and out-of-touchness. Many of these were replicated in the choices of Tory voters themselves, though they also picked a student, representing aspiration, and a soldier, representing patriotism.

Labour’s “mood board” featured a fat man lazing on a sofa, representing people who would rather live on benefits than work, a Division Two football club and the words “untrustworthy” and even “dangerous”, but also included more positive images of an ordinary family and the words “for the many”. While Labour voters’ selections for their own party also featured a doctor and an image for solidarity or a helping hand, many of them also saw Labour as “confused” and “weak”.

All of which supports the idea that people could be open to alternatives. But which people? And what kind of alternative?

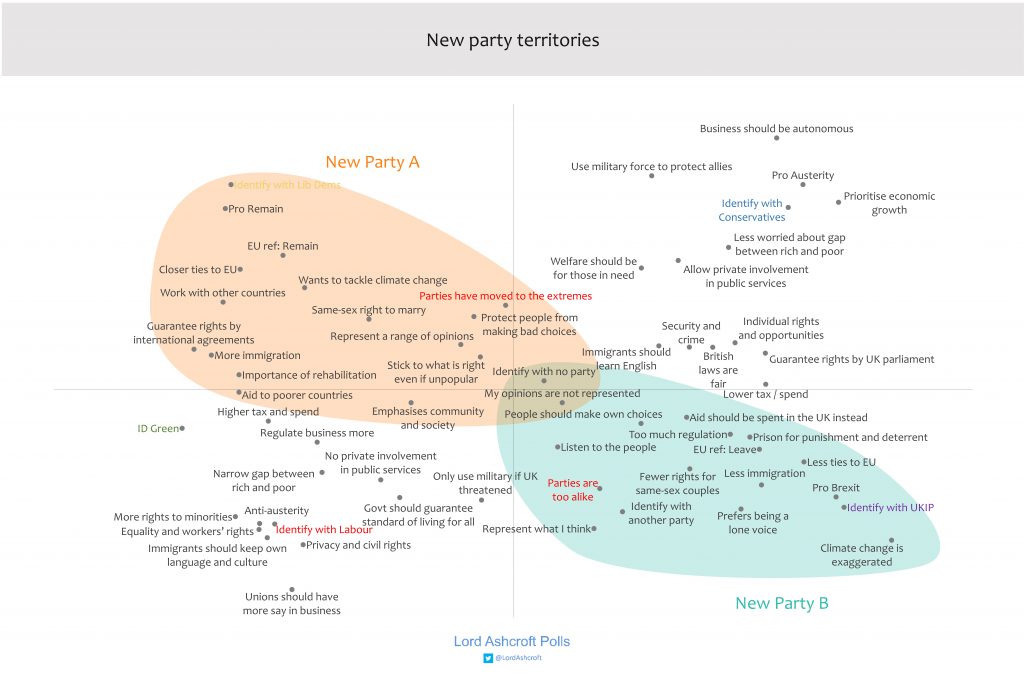

To shed light on this we showed people a series of opposing propositions on a wide range of issues – including immigration, public services, tax and spending, the role of welfare, poverty, overseas aid, business regulation, criminal justice and international affairs – and asked people how strongly they agreed with one or the other in each case. Analysing their responses along with answers to other questions allowed us to map the views that tended to be held by those who identified with one of the existing parties, and those who felt unrepresented for different reasons.

As you might expect, those who identified with the Conservatives – that is, felt an affinity for the party beyond they question of how they voted – tended to accept austerity and private involvement in public service provision, prioritise economic growth over equality and workers’ rights, think government regulated business too much, and to think the gap between rich and poor did not matter much as long as the poor were getting better off. Those who identified strongly with Labour were inclined to the opposite view in each case.

However, there were also a series of views associated with those who felt unpresented because the current parties had become too extreme, and another around those who felt disenfranchised because the parties the parties were too alike. We used these as the basis of two putative new parties. New Party A would emphasise community and society, be happy with current or higher levels of immigration, want more action to tackle climate change, support aid to poorer countries, promote rehabilitation in the criminal justice system, strongly support rights for same-sex couples and favour international co-operation, including the closest possible links with the EU after Brexit. New Party B, meanwhile, would aim to reduce immigration, take a tougher line on law and order, spend the international aid budget in the UK instead, prefer the UK to act independently with few formal ties to the EU after Brexit, and argue that the threat of climate change had been exaggerated, that traditional values had been wrongly neglected and that the government had become too much of a nanny state.

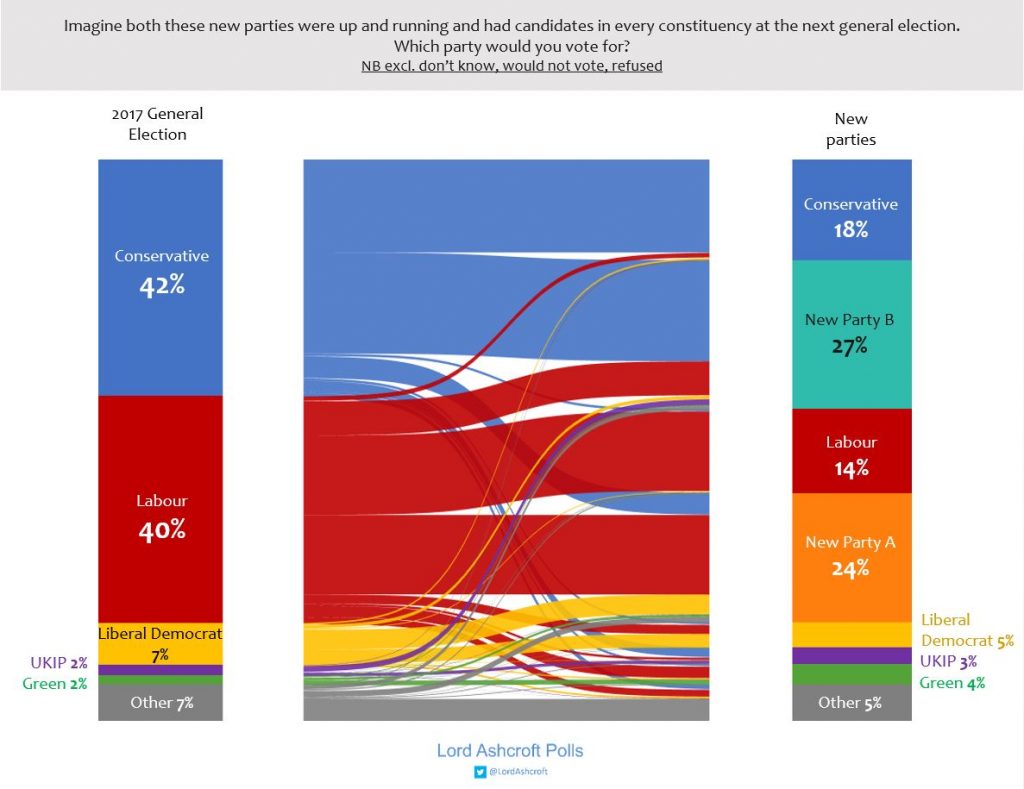

Asked how they would vote in a hypothetical election with these two parties standing in every constituency against the current players, 2017 Labour voters divided evenly between Labour and the liberal, remain-leaning New Party A, as did 2017 Tories between their current party and the socially conservative New Party B – or Her Majesty’s Government, as we might one day come to call it, since it topped our poll, just ahead of its imaginary new rival, with the current governing and opposition parties in third and fourth place respectively.

I am not suggesting this is a likely outcome in any imminent election. But it does demonstrate that there could be an appetite for credible alternatives, and that this appetite does not exist solely on the centrist territory the TIGgers are trying to carve out for themselves.

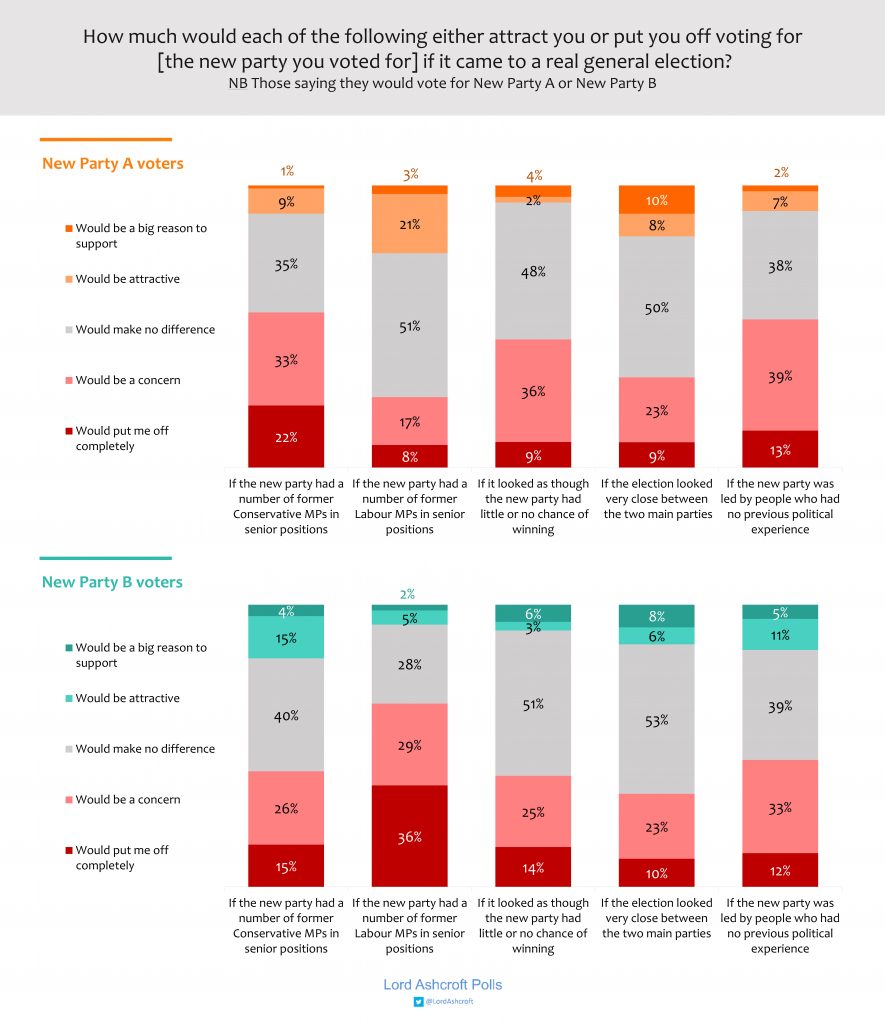

At the same time, the research showed some of the hurdles any theoretical new movement will have to cross if they are to survive contact with reality. Two of these will be quite enough to keep the architects of such an enterprise busy. The first is that unless the party is going to be populated entirely with people previously untouched by politics, they are going to bring with them a certain amount of baggage from their previous berth.

Two in five of those who said they would vote for New Party A said they would be put off completely if they were to find it had a number of former Conservative MPs in senior positions, and one in three New Party B supporters said they would be turned off if former Labour politicians played a prominent role. In our focus groups we found people interested in the progress of The Independent Group but who said they would want a good deal of convincing that Anna Soubry had fully recanted her support for austerity.

The second big lesson for potential revolutionaries is that creating the right policy platform is not nearly enough. As we saw earlier, many feel the parties are all the same in the sense that they don’t do what they say they will do. In an age where manifestos seem worthless, this kind of trust is incredibly hard to generate without a record of delivery to point to. Even many of those otherwise sympathetic to The Independent Group think it already has a case to answer on this score, too: by standing for election on a party label and policy platform and ditching both without endorsement from their constituents, these harbingers of the new order have already committed the oldest political sin.

We don’t yet know what form any change will take, or how soon it will arrive. But those who yearn for it in the expectation that its main outcome will be a resurgence of the liberal centre might do well to be careful what they wish for.