The vote has been deferred while the Prime Minister seeks “reassurances” from the EU, but her message to the House of Commons yesterday was clear – this is the only Brexit deal on the table, and there is no realistic prospect of substantially changing it. Theresa May’s campaign to sell the agreement to sceptical MPs and the public therefore continues. My last survey in late November found that the proposed deal had a cool reception, but with large numbers still to make up their minds. My latest 5,000-sample poll finds shows that more people now have an opinion – but with the balance tipping away from the deal rather than in its favour.

The deal is done?

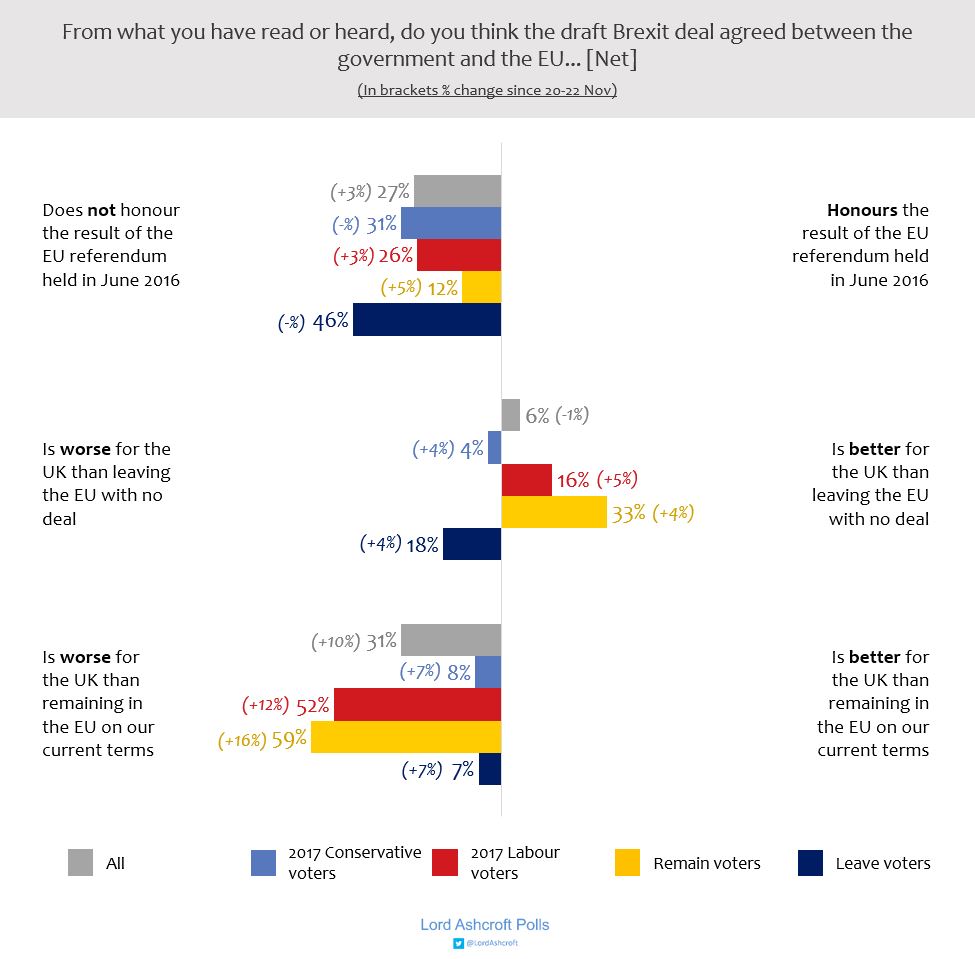

An unchanged 19% say the deal honours the referendum result, while the proportion saying it does not has risen to 46% – including six in ten Leave voters and a majority of Conservatives. The public as a whole says the agreement is better than leaving with no deal by 36% to 30% – and while Remain voters think this by a 33-point margin, Tory voters as a whole now say it is worse, and Conservative leavers think so by 49% to 30%.

Half of all voters now think the deal sounds worse than remaining in the EU on our current terms, with just under one in five saying it would be better. Even Conservative Leave voters are closely divided on this question, with 39% saying the deal beats our current membership package and 38% saying it does not.

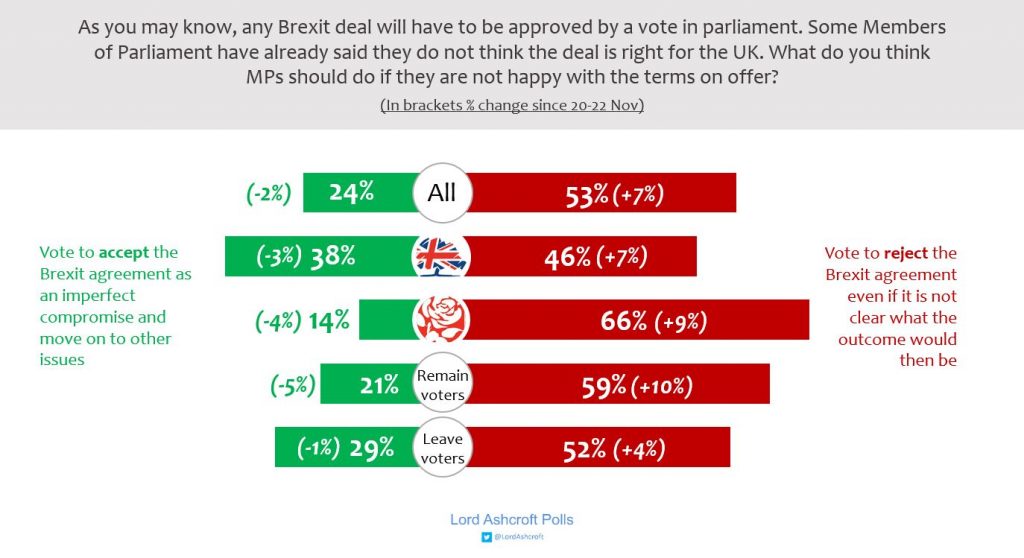

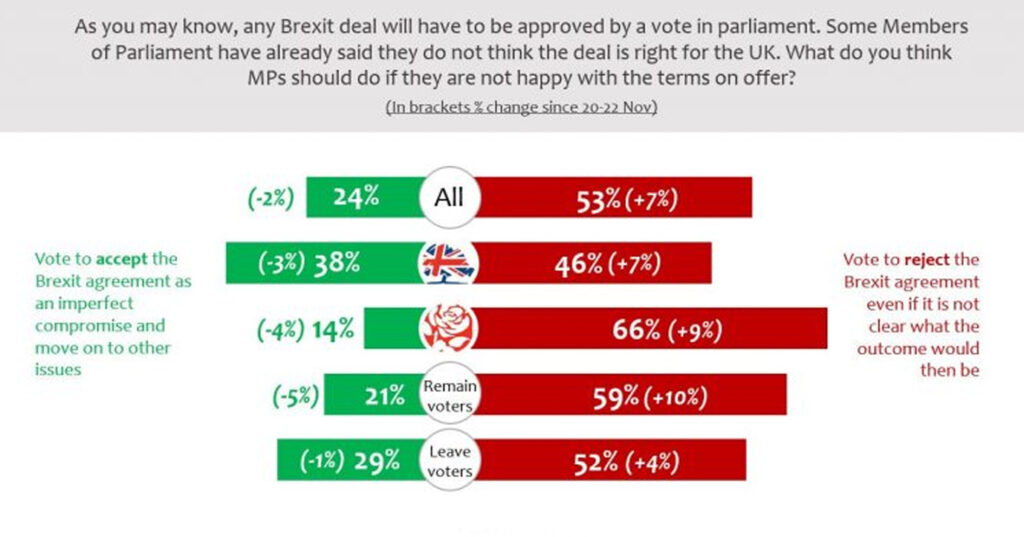

When we asked in November what people thought MPs should do if they did not like the deal – accept an imperfect compromise and move on to other issues or reject the agreement even if the outcome was then unclear – people as a whole chose the latter by a 20-point margin. That has now widened to 29 points, with a majority now saying MPs unhappy with the deal should reject with unknown consequences. Conservative Remain voters, the only group to prefer compromise, now do so by a much smaller margin.

So now what?

While the alternatives to the draft agreement are not altogether clear, there are several possibilities: these include a delay while the government seeks a new agreement with Brussels, leaving with no deal, various forms of second referendum, and a general election. We put these to our poll respondents in different combinations and asked them to choose their most and least preferred options each time (a technique called ‘max diff’ or ‘maximum difference’ which is used in the research industry to give the most comprehensive account of people’s preferences when faced with a list of choices).

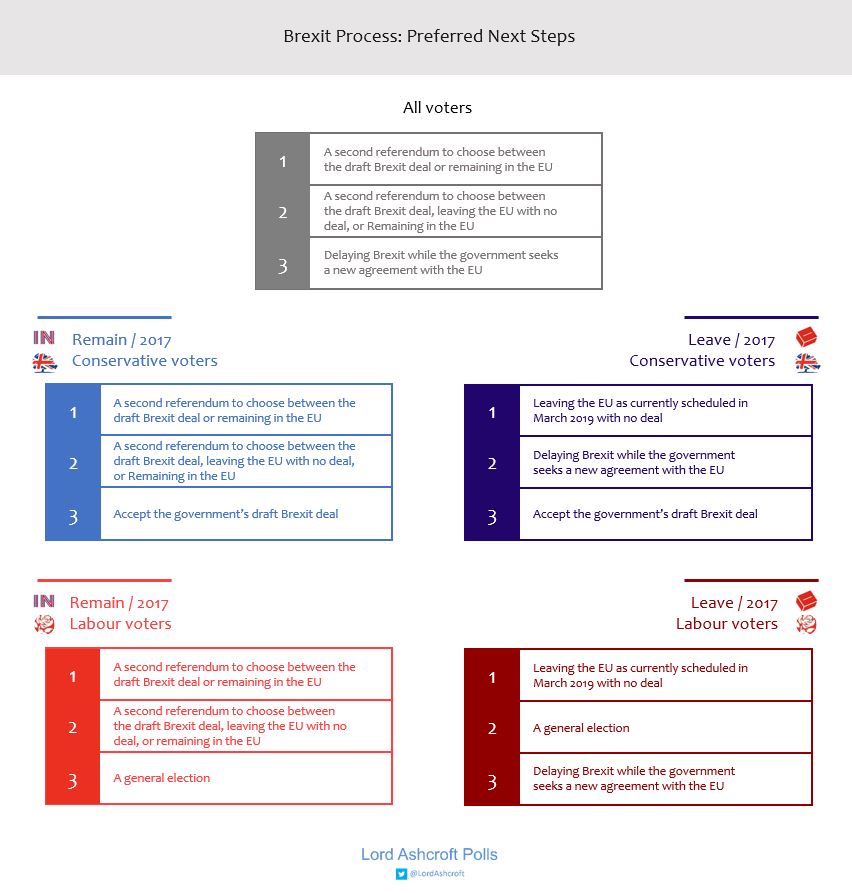

For voters as a whole, there is very little to choose between the four most popular (or least unpopular) options which are, in order, a referendum to choose between the draft deal and remaining in the EU; a three-option referendum on the draft deal, no deal and remaining; delaying Brexit while the government seeks a new agreement; and leaving with no deal. Accepting the current draft deal comes slightly further behind, followed by a general election and – least popular of all – a referendum to choose between the draft deal and no deal.

Unfortunately, this overall list masks wide disagreements between groups. For Conservatives and Leavers, the clear first choice is leaving with no deal, followed by a delay to seek a new agreement, with accepting the current draft agreement in third place. Conservative remainers also put the government’s deal third – but behind the rather different first choice of a referendum to choose between the draft deal and remain, and in second place, a three-option referendum to choose between the draft deal, no deal, and remain. Remain voters as a whole also put these two referendum options at the top of their list, but with a new deal, rather than the existing deal, in third place.

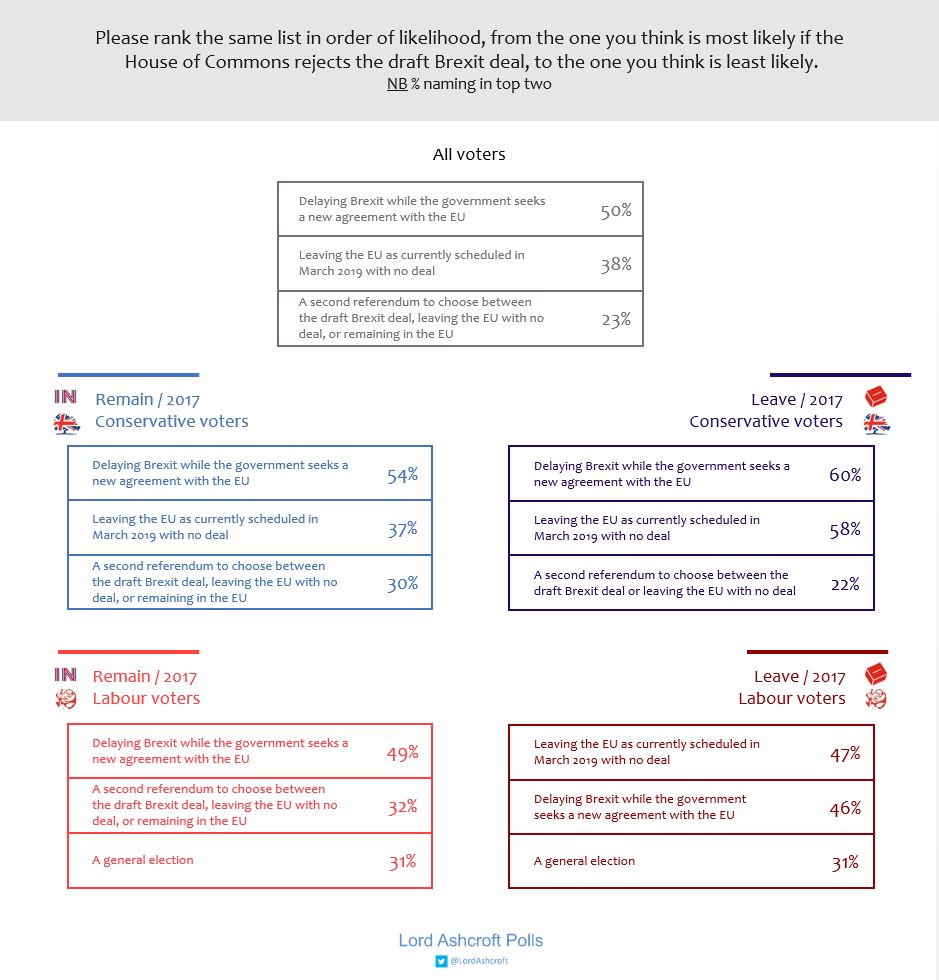

If there is no agreement as to the best next step, there is at least a consensus as to the most likely one if parliament ultimately rejects the draft agreement, in whatever form it is finally presented to the House. This is a delay in Brexit while the government seeks a new agreement with the EU, with a no-deal exit seen as the next most probable. A general election, though less favoured than a second referendum, is regarded as marginally more likely to happen.

Have you got it now?

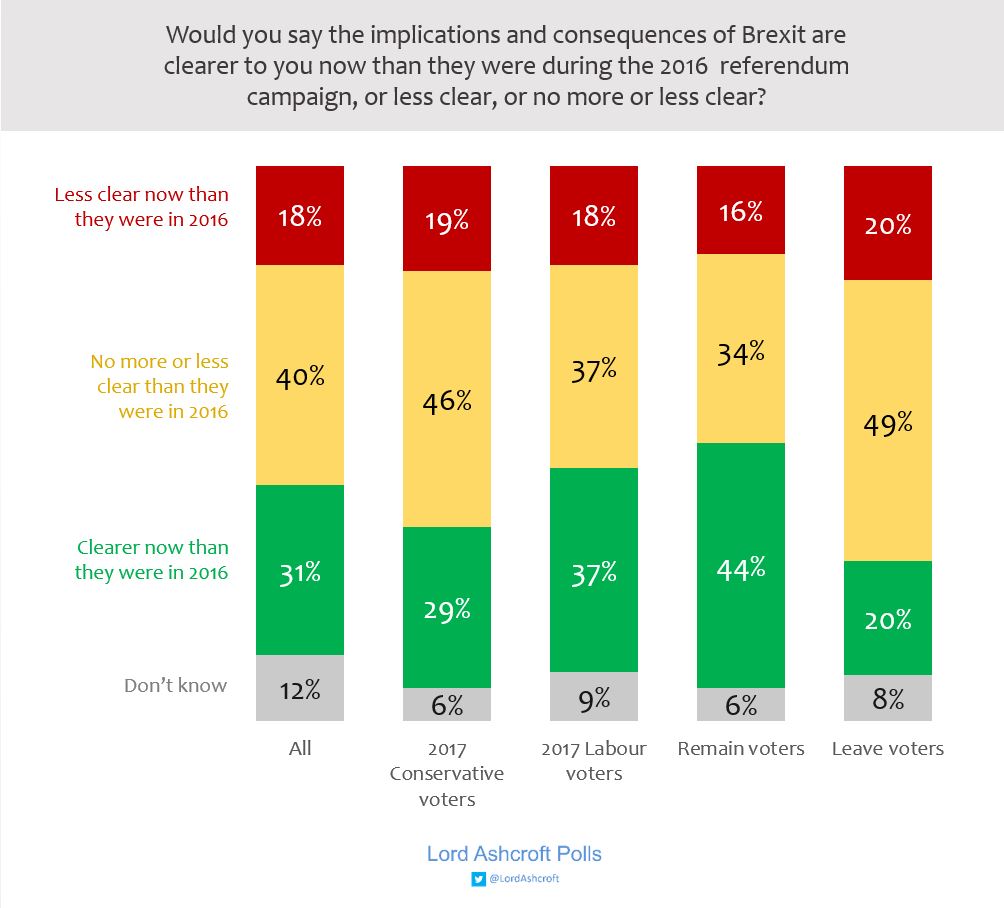

If there were to be a second referendum of one kind or another, do people feel they are any better informed about the choice at hand than they were in June 2016?

According to my survey, only just over three in ten say they are – in fact a majority say either that they are no more or less clear about the implications and consequences of Brexit than they were during the referendum campaign (40%), or that they are even less clear now than they were then (18%).

Back to basics

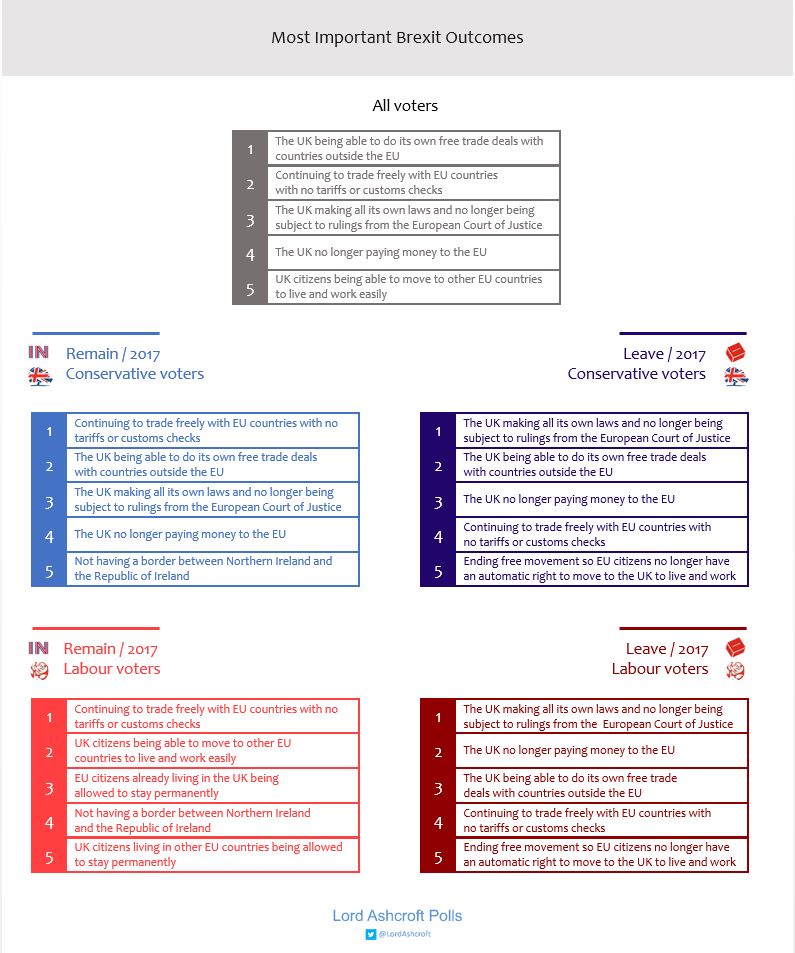

With the Brexit debate now dominated by issues of process and procedure, we went back to first principles to ask again which potential outcomes from Brexit were ultimately the most important. Using the same process of asking people which options mattered to them most and least, we found little to choose between the three biggest priorities for voters as a whole: the UK being free to do its own free trade deals, continued free trade with the EU with no customs checks, and the UK making all its own laws without being subject to rulings from the European Court of Justice.

If the EU would protest that this amounts to an admissible combination of cake-having and cake-eating, there is also little agreement between groups: while Remain voters prioritise frictionless EU trade, UK citizens being allowed to move freely to other EU countries to live and work easily, and EU citizens already in the UK being allowed to stay, Leavers most want to see the UK making all its own laws with no ECJ jurisdiction, the UK making its own free trade deals, and the UK no longer paying money to the EU.

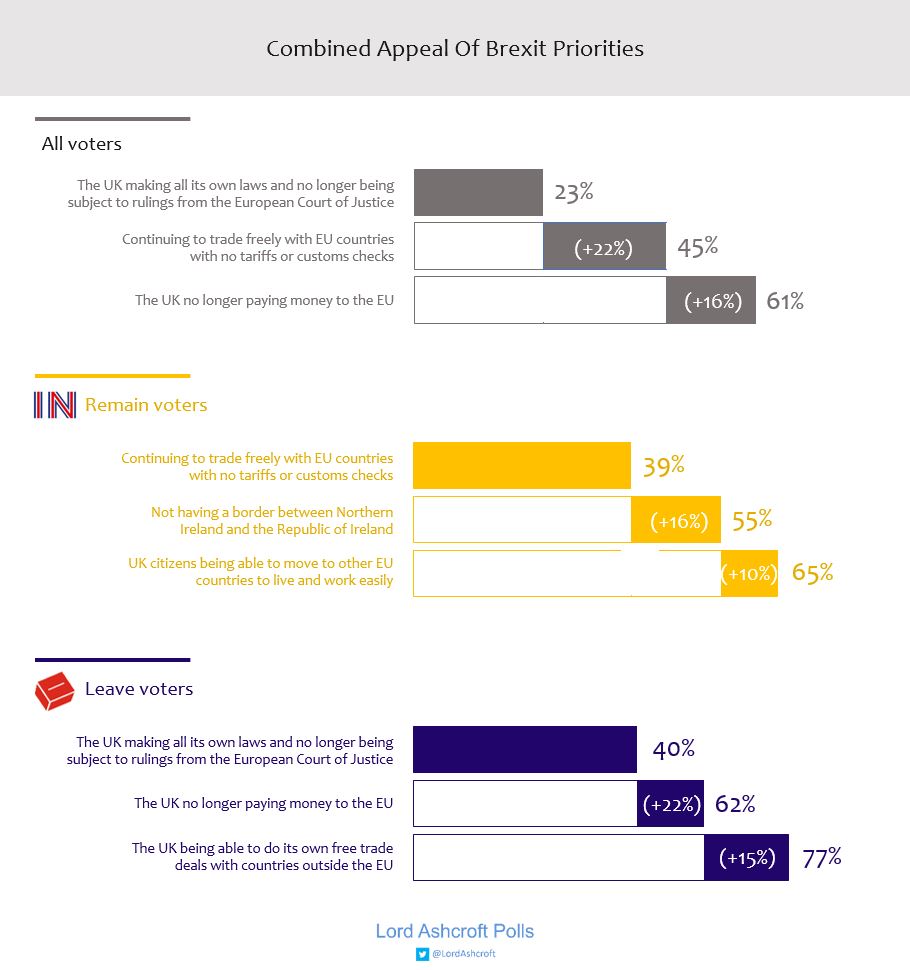

Using TURF analysis, a technique used in commercial market research designed to show which products and services would appeal to the greatest number of customers, we see that a deal combining the UK making its own laws and continued free trade with the EU would include at least one element that appealed to 45% of all voters. Combined with an end to payments into the EU, this would extend its appeal to 61%. As if this were not a tall enough order in itself, the competing priorities from different sides mean there is no deal that could please a majority of Remainers and Leavers at the same time.

Don’t panic

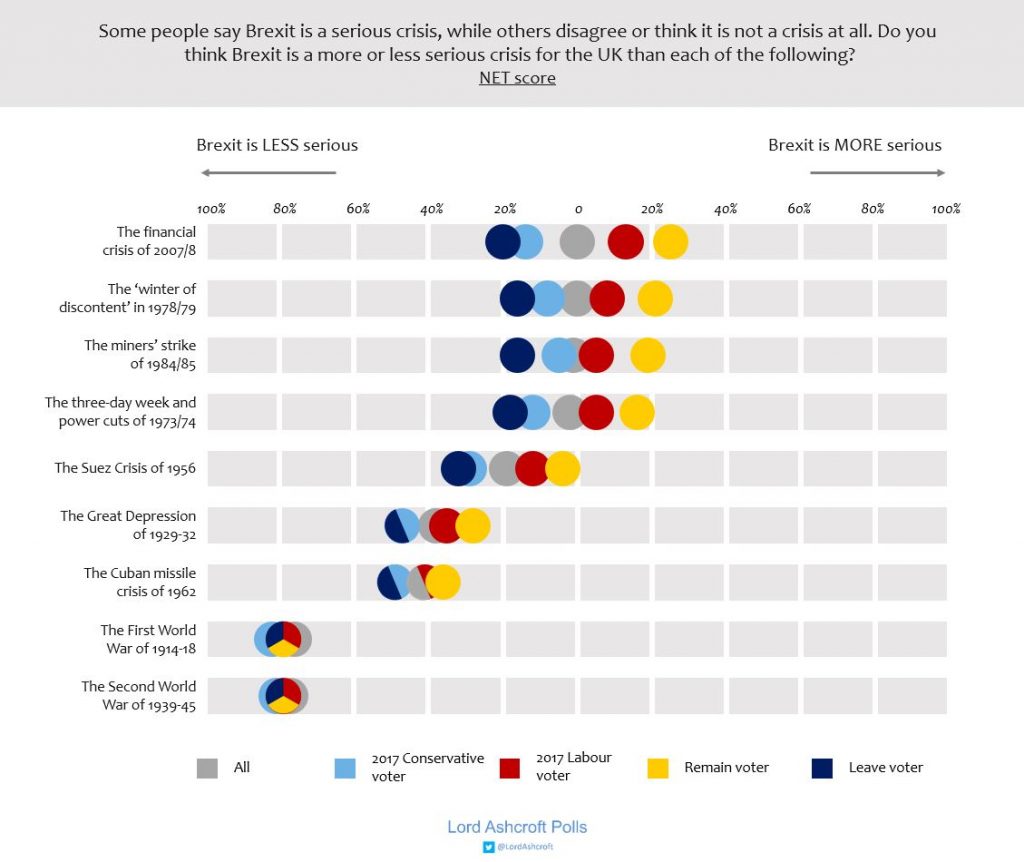

Meanwhile, how serious is the Brexit “crisis” in the great scheme of things, if indeed it is a crisis at all? I found a majority of voters thinking the state of affairs over Brexit was equally or more serious than the financial crisis of 2007-8, with nearly as many saying it is at least as serious as the miners’ strike of 1984-85, and the power cuts and three-day week of 1973-74.

Just over four in ten, but a majority of Remain voters, think the situation is at least as serious as the ‘winter of discontent’ in 1978-79. More than one in ten Remainers think things are comparable to the two world wars, and a quarter of them think there is little to choose between Brexit and the Cuban missile crisis, which could quite literally have brought about the end of the world. And to think some say that people are losing a sense of proportion.