Whether or not they voted Conservative in 2010, most voters expected a Conservative-led government to be tougher on crime, and more effective in dealing with law and order, than its predecessor. When, after the election, the coalition government began to talk about a new approach that placed more emphasis on community sentencing and rehabilitation and less emphasis on prison, I decided to find out whether this was likely to restore confidence in the criminal justice system, or undermine it. Research among the general public, victims of crime, and police officers has produced striking results.

Methodology

General public: An online poll of 2,046 adults was conducted between 18 and 20 February 2011. Six focus groups were conducted between 2 and 9 February 2011. The groups were conducted in Hemel Hempstead, Halifax and Nottingham. The groups comprised equal numbers of men and women and covered a full range of working ages, social groups and voting backgrounds.

Victims of crime: An online poll of 1,001 people who had been the victim of a crime in the last three years was conducted between 18 and 21 February 2011.

Police officers: A telephone poll of 500 serving police officers was conducted between 15 and 23 February 2011. Depth telephone interviews were conducted with 25 serving police officers between 1 and 8 March 2011. Participating officers represented a number of forces throughout Great Britain and ranged in rank from Constable to Superintendent.

Summary of key points

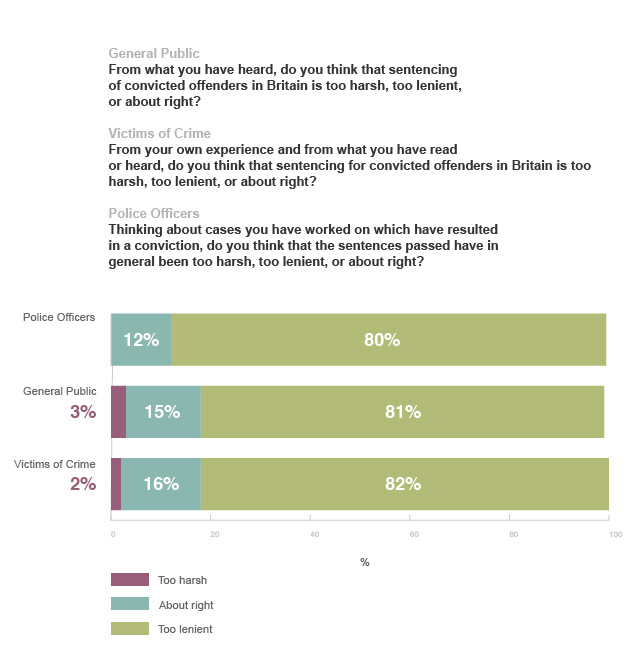

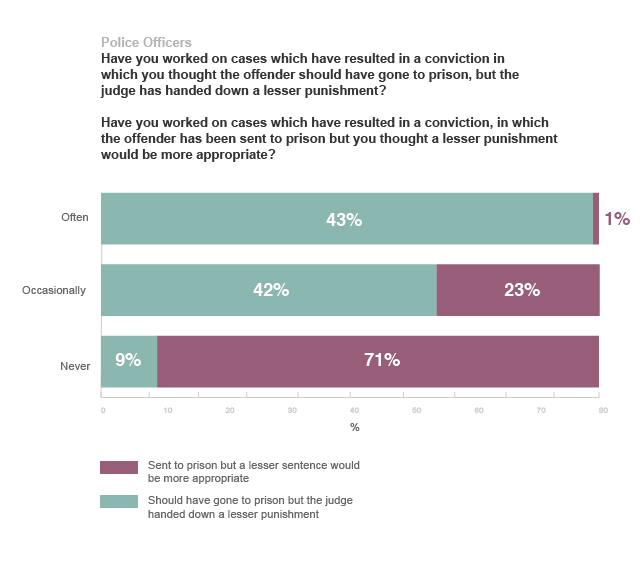

80% of police officers thought sentencing for convicted offenders is too lenient, based on the cases they have worked on. Only two officers out of 500 interviewed thought sentences passed had in general been too harsh. Over 80% of the general public and victims of crime also thought sentencing was too lenient. 85% of police officers had worked on cases where they thought the offender should have gone to prison but the judge had passed a lesser sentence. Only 9% said it had never happened in a case they had worked on.

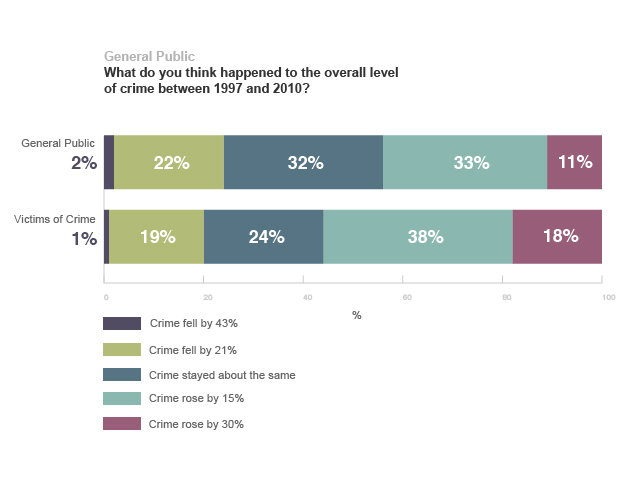

Three quarters of the public thought crime rose or stayed the same between 1997 and 2010. Only 2% thought crime fell by 43% (the figure from the British Crime Survey). Less than a third of serving police officers thought crime was lower now than five years ago. Police officers stressed that local crime rates were heavily influenced by whether a particular prolific offender was in or out of prison at a particular time.

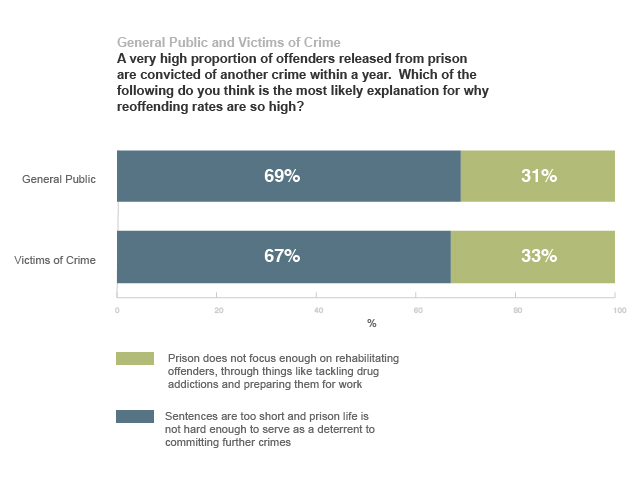

Only 42% of the general public and 38% of victims of crime thought that “prison works”. More than two thirds believed rates of reoffending were high because “sentences are too short and prison life is not hard enough” to serve as a deterrent to committing further crimes”; less than a third thought it was because “prison does not focus enough on rehabilitating offenders”.

Police officers were divided over whether “prison works” (44%) or not (46%). For them, the most important explanation for the high rates of reoffending was that “prison life is not hard enough to serve as a deterrent to committing further crimes”. Second was that “some offenders actually prefer prison to life on the outside”; third was that “prisoners do not spend their time in prison productively”. In interviews, several police officers stressed that prison works in keeping criminals away from the public, even if only for a relatively short time.

Less than a fifth of the general public (19%) and police officers (18%) thought the answer to improving reoffending rates after short prison terms was to give community punishments instead. More than half of police officers (54%) and two thirds of the public (66%) thought the best solution was to “make prison life harder, to make it more of a deterrent to committing further crimes”. Several officers argued that whatever their failings, short sentences were needed as a sanction for repeat offenders and those who breached the conditions of community sentences.

Four fifths of the public and victims of crime saw community sentences as a “soft punishment”, and 90% of police officers thought offenders saw such sentences as a soft punishment. 74% of the public, and 86% of police officers, believed “offenders often commit further crimes while serving community sentences”. Three quarters of both the public and police officers think “community sentences are often given to offenders who ought to go to prison”. Only 19% of the public and 25% of police officers believe “community sentences are effective at stopping offenders from reoffending”.

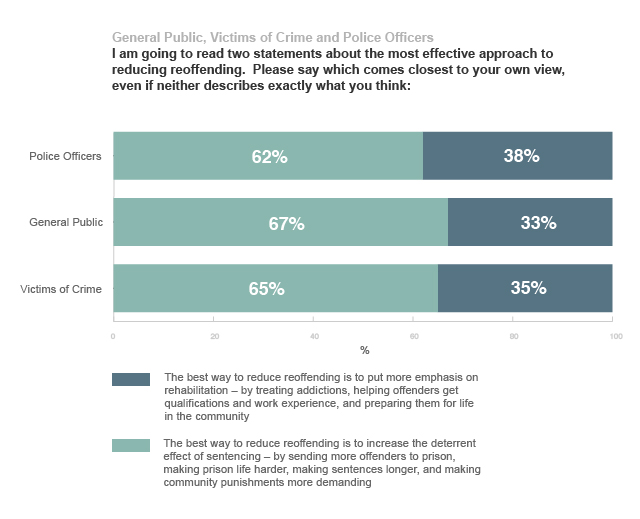

41% of the public and 35% of police officers saw rehabilitation as “a hard-headed, practical way of trying to reduce reoffending rates”. 59% of the public and 58% of police officers were more inclined to see it as “a soft option that tries to make excuses for offenders rather than punishing them properly”. Police officers, like the public, were sceptical about the effectiveness of rehabilitation, particularly for prolific offenders. While drug treatment could be an important part of preventing reoffending, it was very hard to enforce in the community if the offender was unwilling to cooperate. Police officers also stressed that rehabilitation was not an alternative to punishment and containment. Asked whether the best way to reduce reoffending was to “increase the deterrent effect of sentencing” or “put more emphasis on rehabilitation”, 67% of the public and 62% of police officers chose the former.

Just over half of police officers who had heard Ken Clarke’s view on the effectiveness of prison said they opposed it. Officers were concerned that the primary purpose of the government’s review was to save money, or to cut prison numbers as an end in itself, rather than to reduce reoffending and cut crime.

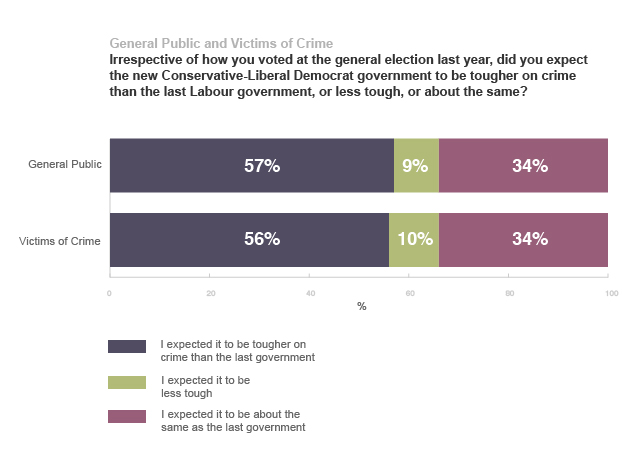

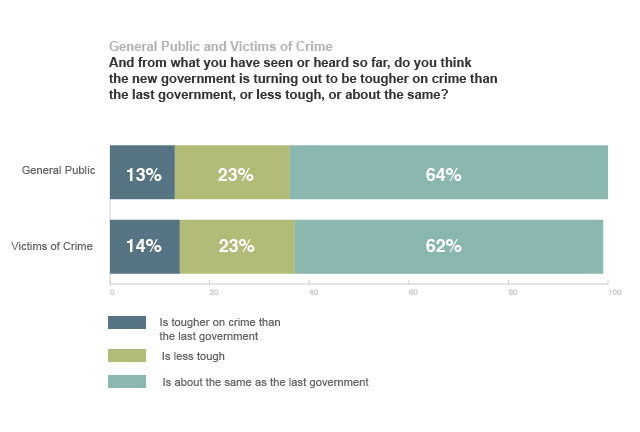

57% of the public expected the coalition to be tougher than the last Labour government in dealing with crime; only 13% thought it was being tougher; 23% said it was less tough and 64% said it was about the same.

The public felt that what they saw as the failure of successive governments to act on their concerns about crime and punishment were due to politicians being unaffected by crime in their own lives; the constraints of human rights law and the fear of being accused of political incorrectness; the criminal justice system being staffed by unrepresentatively liberal individuals; and lack of money. Police officers felt mistakes were made because governments paid more attention to theorists than to victims and practitioners.

Click here to read my commentary on the research, published in the Sunday Telegraph.