The Liberal Democrats have suffered a slump in the polls since their decision to enter a coalition government with the Conservatives. Some have argued that the Lib Dems are finished as an independent party capable of winning significant support at elections, but I suspected things might not be as straightforward as that. I have conducted research among those who voted Lib Dem in 2010, and those who thought about doing so but decided not to, to find some clues about the party’s future.

Methodology

Lib Dem voters: Eight focus groups were conducted in Lib Dem-held constituencies (Eastleigh, Torbay, Hornsey & Wood Green, Redcar) between 4 and 19 November 2010. All participants had voted Liberal Democrat at the 2010 election. A telephone poll of 2,000 people who voted Liberal Democrat was conducted in Liberal Democrat-held constituencies between 18-29 November 2010. The sample was divided evenly between constituencies where the Conservatives came second and those where Labour came second.

Lib Dem ‘considerers’: An online poll of 1,000 people who seriously considered voting Liberal Democrat but ultimately decided not to do so was conducted between 25-28 November 2010.

Summary of key points

Click here to download the full report

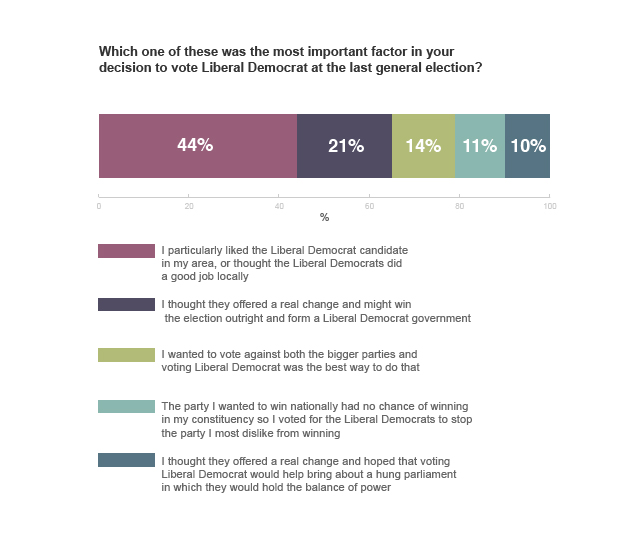

Local candidates, and the perception that the Lib Dems do a good job locally, were the most important motivation for Liberal Democrat voters. A higher proportion of those who voted Lib Dem did so thinking the party might win the election outright (21%) than in the hope that they would hold the balance of power in a hung parliament (10%). For those who seriously considered voting Lib Dem but decided not to, the single biggest offputting factor was the perception that the party could not win and represented a wasted vote.

Those who considered voting Lib Dem but decided not to were more likely to think the party did the right thing by entering a coalition with the Conservatives (55%) than those who did vote Lib Dem (49%). Nearly a third of Lib Dem voters thought the party should have stayed in opposition instead, and a fifth thought the Lib Dems should have formed a coalition with Labour. In the groups, even many Lib Dem voters who do not particularly like the coalition with the Conservatives thought the party had little real choice but to join it.

Those who voted Lib Dem mainly as a protest against the two main parties, or to stop another party from winning, were consistently more negative about the Lib Dems and their performance in government than those who had voted for a positive reason such as local issues and candidates, or the hope that they would win outright or hold the balance of power in a hung parliament.

Asked to describe the Liberal Democrats’ core principles, many in the groups had no idea but the characteristic most often named (which was mentioned in all focus group venues) was a commitment to “fairness”, with some also mentioning “honesty”.

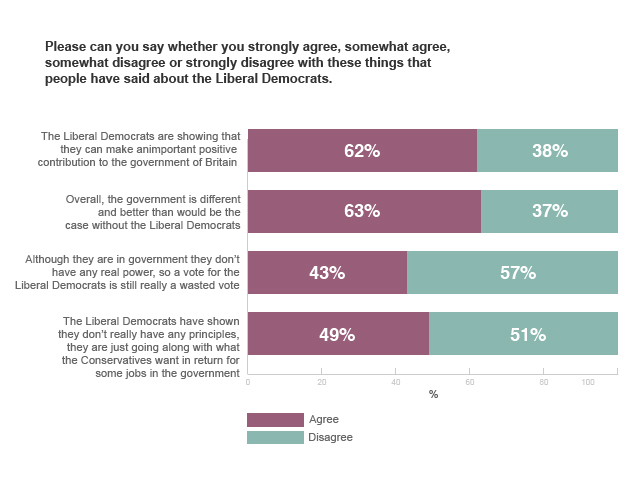

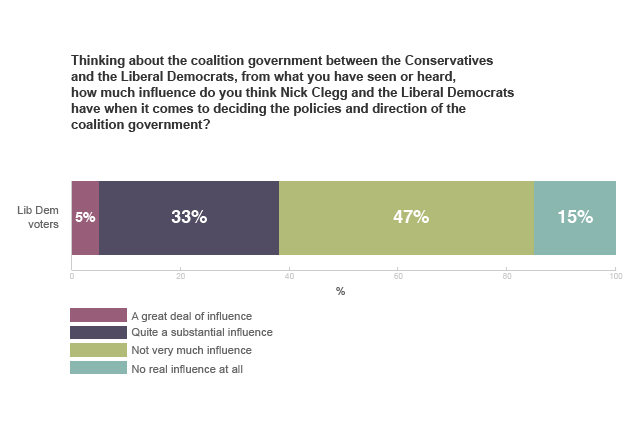

People who considered voting Lib Dem but decided not to were more likely to think the party had a significant influence over the policies and direction of the government (46%) than those who actually voted Lib Dem (38%). In most policy areas, more people thought the party had made no difference than had made policies better or worse. However, majorities of both groups rejected the proposition that the Lib Dems “don’t really have any principles, they are just going along with what the Conservatives want in return for some jobs in the government”. In the groups, several said they thought the Lib Dems had a general “tempering” influence on the Conservatives or had “softened the blow” of spending cuts, though very few could think of examples.

Lib Dem voters felt the two coalition partners were seemed to be getting along very well at a senior level. However, for those who were uncomfortable with many of the coalition’s policies, this public unity made it difficult to know whether the Lib Dems were arguing vociferously in private to get the best deal possible, or (as they suspected) had no real influence – either because they were not being listened to or were offering no resistance.

Some were sympathetic to the senior Lib Dems’ argument that economic circumstances made their commitment to scrap university tuition fees impossible to implement, but most were less forgiving – particularly those who had voted for the party largely on the strength of that policy. Though there was a good deal of condemnation of the party for having broken its promise, at least as much criticism stemmed from its having made such a “naïve” promise in the first place, particularly since it was clear before the election what state the economy was in.

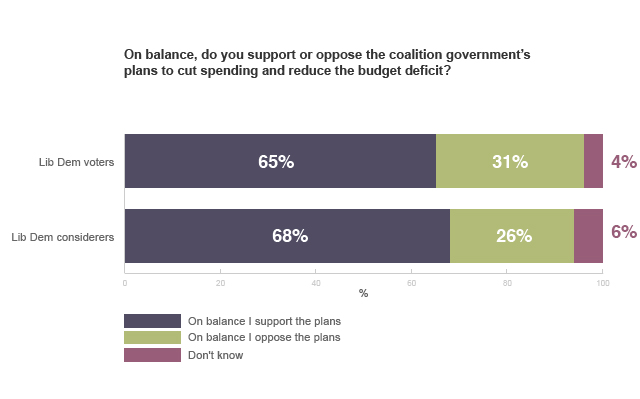

Two thirds of Lib Dem voters said that on balance they supported the coalition’s plans to curb spending and reduce the deficit, though a high proportion were also worried about the pace and depths of the cuts. Support was twice as high among those who thought the party was right to join a coalition with the Conservatives as among those who thought the Lib Dems should have stayed in opposition or formed a coalition with Labour. In the groups several made the point that cuts would have been necessary whoever had won the election. They were particularly supportive of the coalition’s welfare reform proposals, including changes to housing benefit.

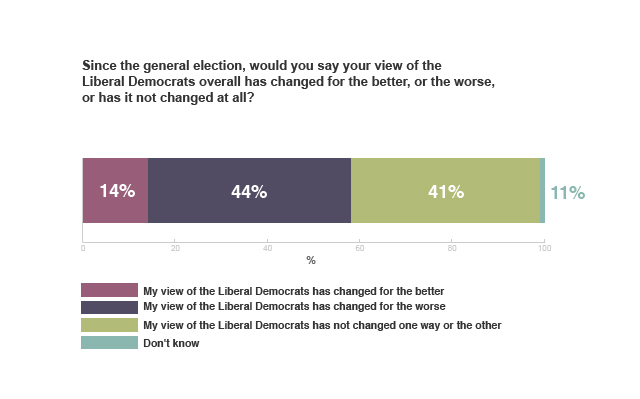

44% of those who voted Lib Dem said their view of the party had changed for the worse since the election, while only 14% said it had changed for the better (though among those who thought the party was right to join a coalition with the Conservatives, 82% said their view had improved or stayed the same). Those who voted Lib Dem as a protest, to stop the party they disliked, or in the hope of getting an outright Lib Dem victory, were the most likely to say their view of the party had changed for the worse.

Among those who considered voting Lib Dem but decided not to, 30% said their view of the party had changed for the better, compared to 38% who said it had changed for the worse. A quarter said they were more likely to consider voting Lib Dem than they had been before (including 41% of those who thought the Lib Dems were right to join the coalition with the Conservatives), but 39% said they were less likely to do so.

Lib Dem voters who were critical of the party often emphasised that they were willing to give it more time to show what it could do. Some noted that they were still happy with their MP even if less so with the party nationally. For those who said their view of the Lib Dems had improved, the fact that the party had accepted the responsibility of a role in government was the most important factor.

Among those who voted Lib Dem in 2010, 28% said they would like to see another Conservative-Lib Dem coalition. The next most popular outcome was a Labour government (27%), followed by a Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition (24%) and a Conservative government (10%). A majority of those who had voted Lib Dem for a positive reason (local factors or to see them in government) wanted to see another coalition involving the Lib Dems after the next election; this was not the case for those who had voted Lib Dem in protest or to stop another party winning.

54% of those who voted Lib Dem in 2010 said they were likely to do so again in 2015. 22% expected to vote Labour, 5% Conservative and 8% for another party. The potential Lib Dem vote was highest in seats where the Conservatives came second (61% of 2010 Lib Dem voters), among those who thought the Lib Dems were right to join the coalition with the Conservatives (75%), and those who voted primarily for local reasons (65%). It was lowest among those who thought the Lib Dems should have formed a coalition with Labour or stayed in opposition (35%), voted in protest against the bigger parties (46%), and to stop the party they most dislike from winning (31%).

Click here to read my commentary on the research, ‘Lib Dems must avoid the temptation to please everyone’, published in the Sunday Telegraph.