When I published the first phase of Project Blueprint in May 2011, David Cameron’s first anniversary as Prime Minister, political comment was dominated by the relationship between Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs following the Alternative Vote referendum. At the end of this government’s second full year, the same is happening again in the aftermath of another of the Lib Dems’ doomed attempts to change the constitution, to the yawning indifference of the country at large. What was true a year ago is even truer now: what should matter most to Tories is not the coalition between the parties, but the coalition of voters who will decide whether to elect a Conservative government with an overall majority.

Click here to download the full report

That Conservative voting coalition will be made up of the four kinds of people who currently comprise what I will call the Conservative Universe. These are Loyalists (people who voted Conservative in 2010 and will do so again), Joiners (those who did not vote Tory in 2010 but have been impressed enough by what they have seen to say they would do so in an election tomorrow), Defectors (those who voted Conservative in 2010 but currently say they would not do so in an election tomorrow), and Considerers (who did not vote Tory in 2010 and would not do so tomorrow, but would consider doing so in future).

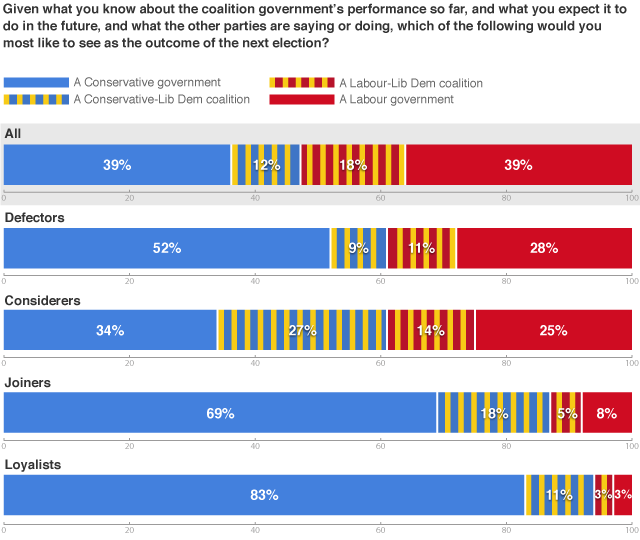

If the Conservatives can keep the Loyalists and the Joiners, win back the Defectors and persuade the Considerers, an overall majority at the next election is possible. Put like that, David Cameron’s task sounds daunting, particularly given the head start for Labour that follows from the collapse in Lib Dem support. It is not surprising that no sitting Prime Minister has increased his – or her – party’s vote share in a general election since 1974.

The mission seems all the more formidable when we look at the apparent differences in political outlook between the four groups. The purpose of Project Blueprint, however, is to understand these different kinds of voters and to identify the things that will bring them together into an expanded Conservative voting coalition rather than divide them further.

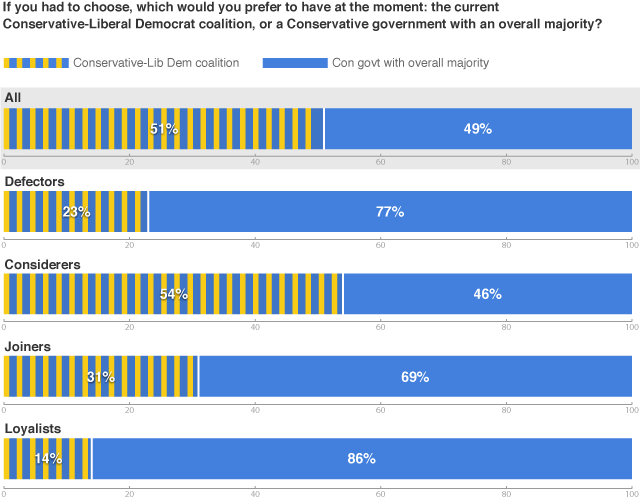

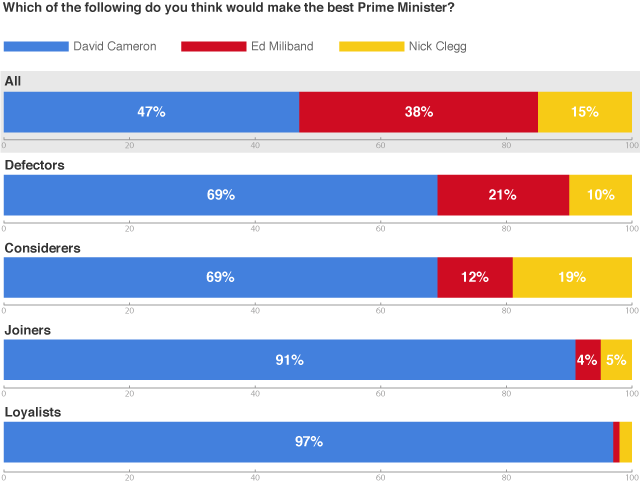

Nearly all Loyalists say the Conservative Party shares their values. The few who do not think that nonetheless say the Tories have the best approach to the economy and that David Cameron would make the best Prime Minister. They are disproportionately aged 65 and above, and in higher social groups. They are the most likely of any voter group to say they are sure how they will vote. They would much prefer an overall Conservative majority to the current coalition. They give the Conservatives a strong lead on all policy issues.

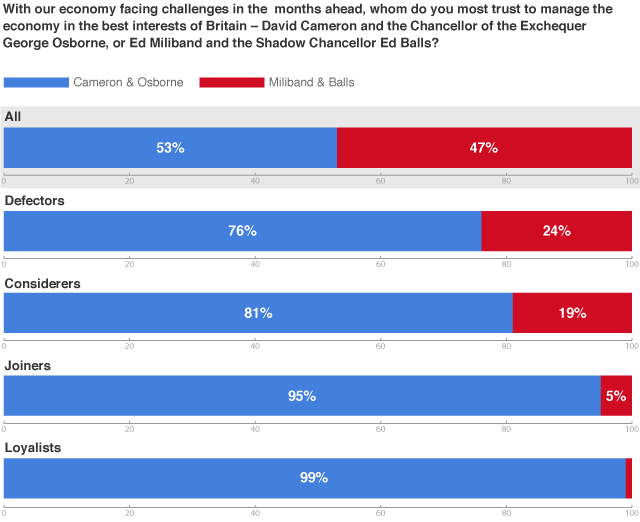

The most important factor attracting Joiners has been the view that the Conservatives are the best party to manage the economy; 95% of them say they most trust Cameron and Osborne rather than Miliband and Balls. They are impressed that the government is sticking to its guns over difficult policies, and are more likely than most voters to give high marks for Cameron’s performance. Two thirds of Joiners voted Liberal Democrat in 2010 and many will still consider the Lib Dems at the next election.

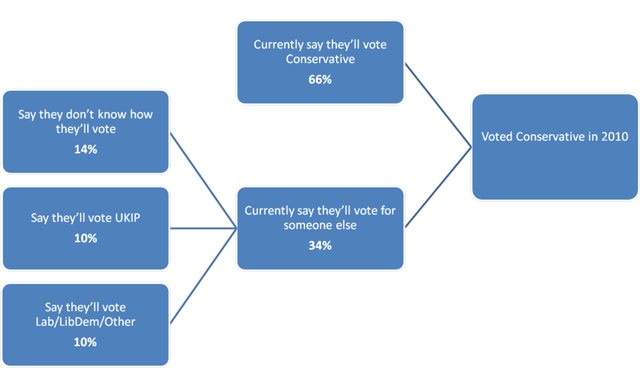

One third of those who voted Conservative in 2010 say they would not do so again tomorrow. Two fifths of these say they do not know how they would vote in an election tomorrow, and most of this group feel the Conservative Party is not on the side of people like them. Around three in ten say they would vote UKIP; this group was most characterised by an opinion that Cameron’s performance had been worse than expected, and a dim view of the Liberal Democrats. The final three in ten Defectors said they would vote for Labour, the Lib Dems or another party. Most of these thought a party other than the Conservatives were best on the economy; if they did think the Tories were best on the economy, they tended to think another party was better at ensuring people were treated fairly.

The thing that Considerers most have in common is that they trust Cameron and Osborne to manage the economy over Miliband and Balls. They are disproportionately likely to say they would vote Liberal Democrat in an election tomorrow. Unlike Loyalists, Joiners and Defectors, they prefer the coalition to the prospect of a Conservative overall majority. They are no more likely than voters in general to think the Tories stand for fairness or equal opportunity.

People who think the Conservative Party shares their values, then, are already very likely to say they will vote Tory. For other potential supporters, the relationship is much more transactional: their votes will depend on the job being done. This is partly a truism, since successful parties are always the ones whose attraction extends beyond their natural supporters. And it is not to say that values don’t matter: whether you think the government wants to control spending for the good of the country or because it dislikes poor people will be an important factor in your voting decision. But the nature of the Prime Minister’s electoral challenge makes it all the more necessary to understand what the transaction will be based on.

The fact that economic management is the most important single factor in building the Conservative voting coalition is good news for the Tories. However, although most members of the Conservative universe say (with varying degrees of reluctance) that austerity is the right course, few think very much progress is being made. Most people greatly underestimate the proportion of the deficit that has been eliminated so far, and some even think it has grown. When told that the deficit has in fact been reduced by a quarter, they are pleasantly surprised. It tells them that the policy is working, and that there is an end in sight, even though it is some distance away. They cannot understand why the government does not make more of this achievement. The answer, I suspect, is that they fear it reminds people just how far there is to go and, by implication, how many cuts are still to come. In fact, I think the government can be bolder in talking about this. Those who are likely to vote Conservative or could be persuaded to do so accept intuitively the need to control spending, but they sometimes wonder whether it is doing any good or when it will all end. Knowing that it is working has a galvanising effect and adds weight to the argument that the government needs time to see its plan through.

The bad news is that the air of competence and leadership necessary to trust a party to run the economy is being eroded. Voters we spoke to had not failed to notice the number of U-turns the coalition had performed in recent months. For a government to change its mind was not a bad thing in principle, and could be a sign that it was listening. However, the number of reversals suggested to people that policies were not being thought through properly. Many recalled the ‘pasty tax’ debacle with some derision. Few had strong views about whether warm baked goods should or should not be subject to VAT at the standard rate – they just thought pasties were a ridiculous thing for the government to get itself into a long row about.

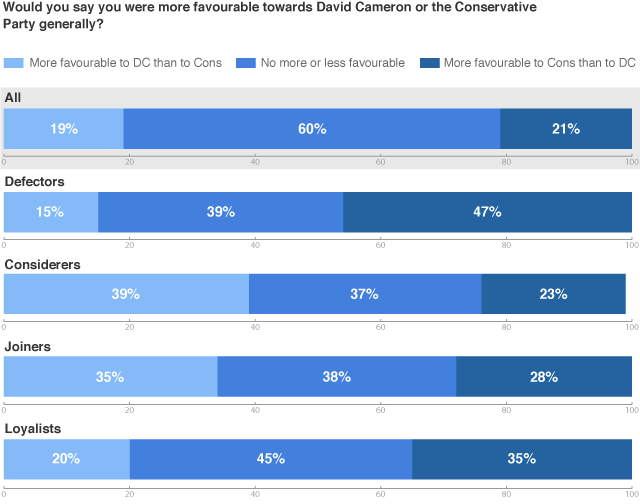

Despite his declining personal ratings, David Cameron himself remains by far the Tories’ biggest asset. He outscores all other national politicians among Loyalists, Joiners and Considerers, and even Defectors see him as the best available Prime Minister by a substantial margin. He has been an essential attraction for those who have switched to the Tories since 2010, and is more attractive than the Conservative Party as a whole to those who do not yet vote Tory but may one day do so. For Loyalists, Joiners and many Considerers, Cameron is doing a decent job of trying to get things back on track despite having no majority and no money.

It is not too much of a generalisation to say that while Loyalists and Joiners think Cameron and the Tories are doing the right thing by the country despite the constraints they face, Considerers are not yet persuaded of this, usually because of concerns about the impact of the cuts or their view of the Conservative Party more generally. Defectors, more than other groups, think Cameron is unable or unwilling to do the right thing by them – either because they have been hit by austerity policies, or because they feel the coalition is preventing the kind of Conservative government they want to see.

It is understandable that a party should pay more attention to potential Defectors than to potential Joiners. Certainly the Tories do not want to lose any voters if they can help it. But it would be a mistake for the party to focus only or even mainly on the Defectors. They are more likely to say they don’t know how they will vote than that they will vote for any other party, and most say they would rather see an overall Conservative majority than anything else. We should not take them for granted, but nor should we set the agenda according to what it is sometimes claimed they want. Even among Defectors we found very little enthusiasm for an early referendum on Britain’s EU membership. Though several did have complaints about Europe, their biggest grievance was very often the constraints imposed by the European Court of Human Rights – something that can be addressed without an EU referendum, and indeed that an EU referendum would not address. Conservative-minded Defectors were often frustrated by the fact of the coalition rather than any specific policy failure.

The votes of people who did not support the Tories in 2010 but might be persuaded to are worth as much in the ballot box as those of previous Conservative voters who might defect. Intriguingly, our analysis found as many potential Conservatives who voted Lib Dem at the last election as 2010 Tories who now say they will vote UKIP. If we are to win a majority, these two groups are equally important. For these potential Joiners, as well as other Considerers and Loyalists, it is the economy that matters most. There are more votes to be lost by adopting a more overtly right-wing agenda than there are to be gained.

Is it possible, then, to square the circle – keep the Loyalists and Joiners, win back the (often UKIP-leaning) Defectors and persuade the (often Lib Dem-leaning) Considerers? Yes it is. But we cannot please all of the Conservative universe all of the time. Everything the Conservatives do between now and the next election must pass at least one of the following four tests, and it must not fail any of them.

First, does it show we are sticking to the right priorities for the country? Secondly, does it show strong leadership? Thirdly, does it show we are on the side of the right people (and, if necessary, make the right enemies?) Fourthly, does it offer some reassurance about the Conservative Party’s character and motives?

Sticking to the deficit reduction programme passes all four tests. So does welfare reform, provided people can see it helps people towards a better life and protects those who still need help, as well as weeding out scroungers. Well thought-out immigration policy fits too. Even tough European policy, such as last December’s veto, can qualify, though embarking on a time-consuming referendum campaign would so dominate the government’s agenda that it would fail the first test.

The NHS reforms, meanwhile, arguably failed all four. Bringing forward proposals for Lords reform was unavoidable because of the coalition agreement, but there is no case for spending any more time on them in this parliament.

Many Conservatives, up to and probably including the Prime Minister, are frustrated with coalition politics at Westminster. To be free of it, though, we must recognise that outside parliament, all politics is coalition politics. The four kinds of people I have identified represent the only winning coalition open to the Conservative Party, and the four tests I have proposed will help make sure we meet as many of their shared aspirations as we can. It may be difficult to do, but it is not complicated to grasp.