In my last poll, a 2019 Conservative voter’s average likelihood of voting Tory again at the next election was 48 out of 100. The first in my series of regular 2024 focus groups – in Bolton West and Middlesbrough South & East Cleveland – included those who put their own chances of repeating their Conservative vote at 3 to 5 out of 10, on the reasoning that if anyone is going to bolster the party’s poll numbers in the coming months, these will be the people. Judging by what they had to say, a recovery is not yet imminent.

The groups took place as the week’s parliamentary procedural drama had fully unfolded (not that most voters care about parliamentary procedural dramas or even notice them). However, people had certainly clocked Keir Starmer’s Gaza quandary and even detected a readiness to shift his position under pressure. Some appreciated his stance: “He stood by Israel for quite a while, I liked that. They’re all pro-Palestinians in Labour and he was for Israel, saying it was terrible what had happened;” “I had the same feelings, that Israel had a right to do what they did after the attacks, but it’s gone on and on and on and now I think the same as him, let’s just have it stopped.” Some, though, felt that rather than acting on principle Starmer was “playing a very careful game” on the issue: “He’s scared because the rest in his party are saying ‘look, we’ve got millions of Muslims that vote Labour, just be careful what you say’. And he’s going along with what they want.”

Nor were our participants much impressed with what most regarded as the confected ‘transphobia’ row following last week’s PMQs. A few thought Rishi Sunak ought not to have mentioned Starmer’s travails over the definition of a women given the presence of Brianna Ghey’s mother in the Commons (“It was a lazy comment… Sometimes his brain doesn’t engage”) but more were indignant with Starmer than with the PM: “It wasn’t transphobic. It was about Starmer changing his mind on things and going back on policies. And Labour jumped on it with both feet and got it wrong;” “What Starmer did was out of order, and he did it deliberately because she was there;” “He twisted it, he took it out of context.”

They’re debating issues I have never cared about… Just crack on, OK?

Notably, some were angry that political attention seemed to be consumed by what they regarded as irrelevant questions. “I’m getting more and more turned off with what they’re talking about. They’re debating issues I have never cared about in my 44 years. I couldn’t find Gaza on a map. I don’t care about the woke stuff. I’ve struggled to get my daughter into a good school, I can’t get a doctor’s appointment for love nor money. How are my kids ever going to buy a house? Just crack on, OK?”

Issues people mentioned spontaneously included imminent council tax rises, together with extra costs (“they’re going to charge us extra for the green bins”; “we’re paying more for less services”); striking doctors; struggling local services; mortgage rates; uncertainty over the government’s free childcare scheme; decaying infrastructure and – despite falling headline inflation – the cost of living, still including food, fuel and energy prices.

Another £4 billion on the NHS and all you’d see is more managers and diversity.

None had high hopes for the spring Budget on 6 March (“none of us is going to go ‘whoopie!’ It’s not going to make our lives any better or any worse”) and most were doubtful about Tory calls for the chancellor to cut taxes. “There’s too much debt, all this money they spend on covid furloughs, shopping vouchers, the injections. It all has to be paid for;” “It’s going to have an impact on budgets. There’s no money, so they’ll just get it from somewhere else”; “It’s the tax bracket that needs to move, not the rate. That makes people feel better than cutting 2p off in the pound.” Though some called for more investment in public services, some were doubtful about directing surplus funds to the NHS: “It’s just going to be swallowed up and never seen again. You could stick in another £4 billion and all you’d see is doctors getting a pay rise, and more managers and diversity.”

Many of these 2019 Tories were also baffled and exasperated by what they saw as the failure to control immigration, and particularly the apparent inability to stop the boats. Particular concerns included the cost of hotel accommodation (“I couldn’t believe it when I heard. I honestly didn’t think the country had that much money to spend”), the extra demand for housing and public services, the fact that such a high proportion of supposed refugees are young men, the effect on crime (“we don’t know who we’re letting in”), and the length of the process. Asked why the problem seemed so intractable, some blamed “all the snowflakes, the human rights people, the do-gooders, the lawyers”. More often, they blamed an absence of the political will needed to tackle it – whether the pull factors (“they are coming through countries that are safe to get here. Why don’t they seek asylum in the first safe country?”; “they get housed, they get clothes, they get money – you can’t blame them, can you?”) or the lack of enforcement (“faster deportation. They’re in deportation centres for ages, then they have the right to appeal”; “Tony Abbott of Australia did the right thing, went out with his boats to turn them back. France has got to take responsibility and take the buggers back”; “nobody wants to get involved, they’re too scared. The police aren’t allowed to police and the politicians aren’t allowed to say yes or no”).

Despite this, many were bemused by the Rwanda policy. Some were not sure how the scheme was supposed to work (“it’s a bit random”) or why Rwanda had been chosen. Even those who thought “it wasn’t the worst idea” doubted that Sunak would win his £1000 bet with Piers Morgan that a Rwanda-bound plane would take off before the election.

I expected him to have a bit more oomph about him.

Opinions of Sunak tended to follow a few themes: that he is out of touch with normal people (“he doesn’t know what’s going on really, does he? I don’t think he’s in our world;” “I remember once he said ‘I’ve got no working-class friends’”; “I was on my pushbike in Richmond and he was doing a tour in the constituency, and he just looked a bit too slick”; “I find it hard to swallow that a millionaire is telling me to tighten my belt”); that he doesn’t seem very inspiring (“I see him as a bit of a cardboard cut-out. He doesn’t have any charisma or personality. He doesn’t fill be with any confidence;” “when he’s speaking, I don’t go ‘oh, Rishi’s talking, I wonder what he’s got to say’. I’m not really interested;” “he’s non-committal. When he’s challenged on stuff he won’t give yes or no answers, he doesn’t commit, he just sits on the fence”;) or that despite a good record as chancellor during covid he doesn’t seem to be very effective (“I think there’s no trust or faith in him”; “he seems a bit naïve and inexperienced”; “I expected him to have a bit more oomph about him”).

Some were less harsh: “slow but steady, he’s getting there;” “things have just been against him. I’m willing to give the guy a chance”; “his main problem is that if you go below him they’re all idiots. It’s like shuffling deckchairs on the Titanic with the rest of the cabinet”. Asked what they would put in a kind eulogy for the 14 years of Tory rule, people mentioned cost of living payments, the energy cap, the early years of trying to reduce the debt, the vaccine programme, furlough, and weapons for Ukraine. Getting Brexit done was rarely mentioned spontaneously.

I can’t think of a word because he doesn’t make any impact on me in any way at all.

Though benefiting from these attitudes to the Tories, Keir Starmer fared little better at the hands of what must be his target voters. Asked to sum him up, participants’ answers included “nondescript”, “pompous”, “smarmy”, “indecisive” and “I can’t think of a word because he doesn’t make any impact on me in any way at all”. A regular complaint was that “he does the opposite to what Rishi says to make himself look good. But I don’t think he does look good” and that Labour seemed to have no plans to speak of: “just the green thing, but obviously they’ve pulled that now because they haven’t got the funds to do it”; “Labour knocked on the door the other night, so I said ‘what are your policies? What are you offering?’ He was like, uh, shall I come back nearer the election?’”. A more generous interpretation was that “he’s playing a long game, not really saying much because he knows they’ll win it.”

Though all agreed that the Starmer was an improvement on Corbyn, many doubted that the party had changed as thoroughly as the leadership would claim. The Rochdale episode was cited in support of this view: “He’s better than Corbyn but the undercurrent of the party… I’m just not completely convinced. I don’t think they’re all on the same page as him;” “they’re hiding their dirty washing;” “every time you think it’s changed, somebody pops up and you’re like, oh Christ, here we go again.” A few also worried about outside influence: “Rachel Reeves and the ginger one, they’re going to pull his strings, and they’re very unionised.”

They are the Conservative party but with balls on.

If people were (to say the least) doubtful about both main parties, what did they think of Reform UK? “They’re more conservative than the Conservatives. They are the Conservative party but with balls on;” “I like the way they speak. They’re very strong about immigrants, they want to lower taxes, they want to make us strong as people;” “There’s a new guy in it who’s incredible. I’ve forgotten his name though”. Others were sceptical: “It’s like ‘once more with feeling’ isn’t it. It was vote UKIP – didn’t work. Vote Brexit – didn’t work. Now it’s Reform UK, go again, louder, say it with more belief. Yeah, it hasn’t worked;” “It’s an alternative, but it ain’t going to get anywhere.”

*

And finally: this being the awards season, who would play Rishi Sunak in the Netflix miniseries dramatising the story of his life? “Hugh Grant;” “The guy with the briefcase from The Inbetweeners;” “Someone quite nerdy who looks like he’s won a raffle to be prime minister.”

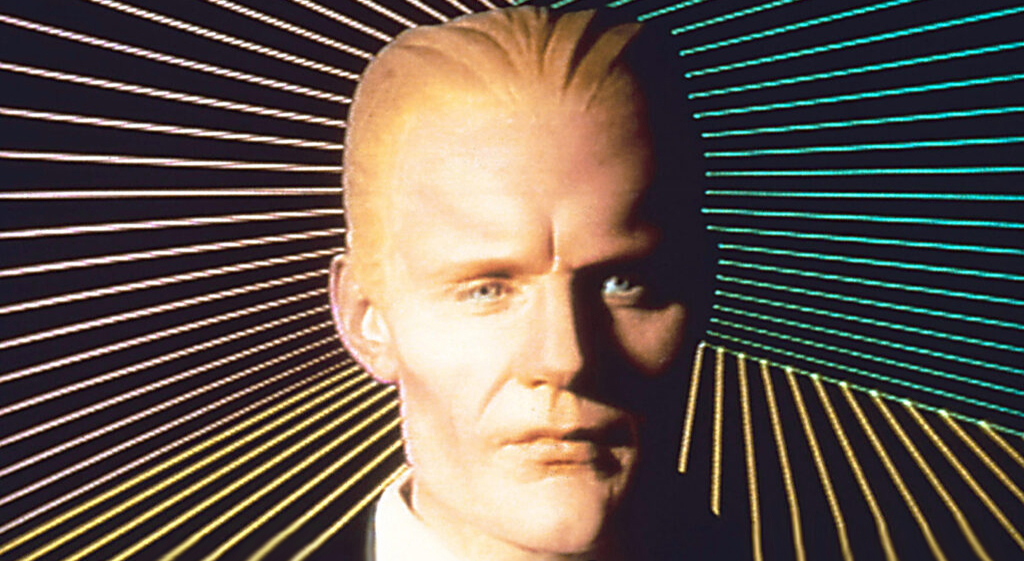

And who would play Sir Keir? “Max Headroom;” “The Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz;” “Frank Spencer, he hasn’t got a clue what he’s doing;” “Keanu Reeves. Because he’s so absolutely against confrontation, if someone says to him ‘one plus one is five’, he’ll say ‘absolutely it is’.”