Most Londoners think life in the capital is getting worse and many think they have little to show for Sadiq Khan’s seven years in the Mayor’s office – so why, with six months to go, does he seem to be cruising to re-election? My latest polling of nearly 3,500 Londoners, together with focus groups around the capital, helps explain.

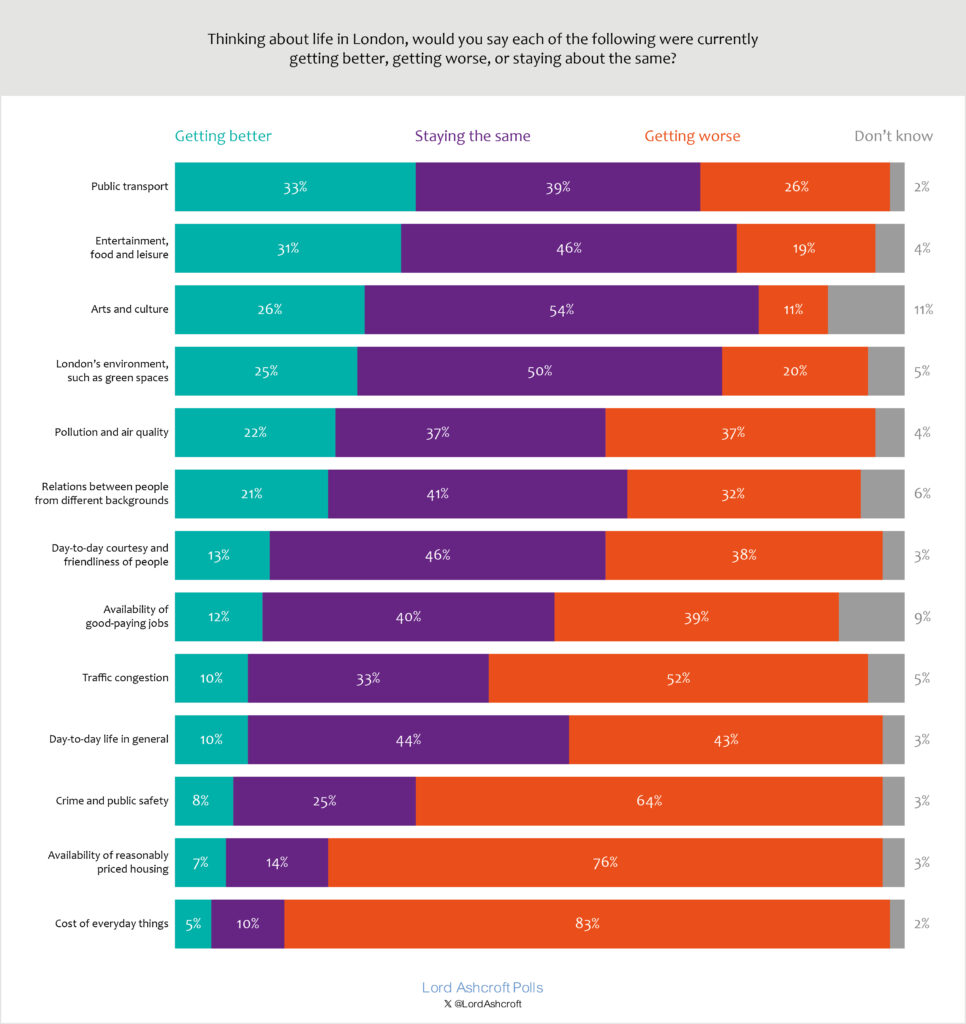

We found four areas in which Londoners were more likely to think things were improving than deteriorating: public transport, entertainment and leisure, arts and culture, and the city’s environment, such as green spaces.

But many more thought day-to-day life was getting worse, and majorities thought things were going downhill in four crucial areas. Living costs were recognised as a universal problem not confined to London, but others were more specific. Worsening traffic congestion often seemed not to be caused by the volume of cars but by Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, parking restrictions and other initiatives whose effect was to exacerbate problems or shift things to other areas, and which seemed designed to rake in cash from charges and fines rather than address practical problems.

Most people believed that crime was getting worse, often from their own experience and observation. We heard some hair-raising stories from people worried that crimes of all kinds, including serious and violent incidents, were increasingly prevalent in places where they had until recently felt safe and secure. Many lamented the closure of local police stations and said officers were hardly ever to be seen in their neighbourhoods. For many in the outer boroughs, crime was a tangible example of a feeling that the less desirable elements of inner London were spreading into their territory.

The shortage of affordable housing was also a major theme, both for younger people wondering if they could afford to stay in the capital and older generations wondering about prospects for their children. People reported snapping up a flat they had not even seen, such was the scarcity of properties. They acknowledged that new housing was being built, especially high-value apartment blocks, but wondered who could afford to live in them.

When we asked people what they thought should be the Mayor’s main priorities and how good a job he had done on each, most of the scores were fairly middling – but in general, the more important the issue, the worse his perceived performance. Though voters gave him good ratings for attracting international investment, investing in the arts and speaking out against the government, they gave him their lowest score for their biggest Mayoral priority – which was tackling crime.

Few could recall Khan’s specific pre-election pledges, but they believed he had promised improvements in areas including crime, housing, transport and the environment. Some thought there had been successes, which for them included free school lunches, holding down public transport fares and efforts to improve air quality, but most felt major improvements had been lacking.

None of this should augur well for an executive Mayor seeking a third term of office, but there are perhaps three crucial political factors in his favour.

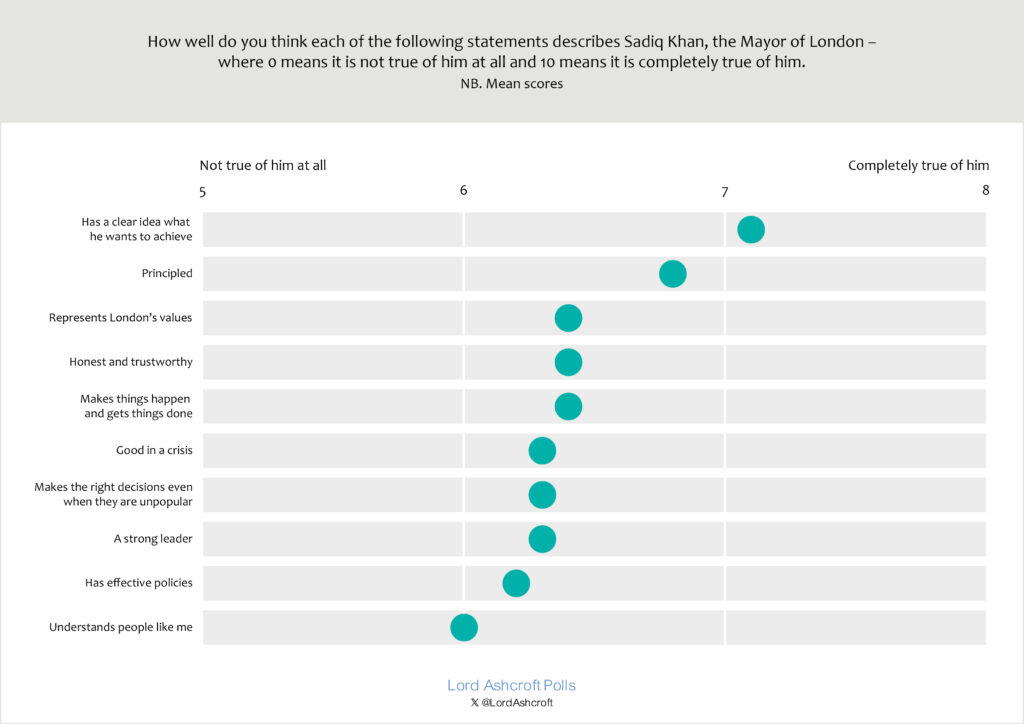

One is that Khan is not personally unpopular. His personal ratings are reasonably good, for a politician, though it is notable that people award him higher scores for being principled and knowing what he wants to achieve than they do for his having effective policies.

In our focus groups we heard that whoever they voted for, people from all walks of life liked the idea that a Muslim son of a bus driver should have become Mayor of London and that this in turn said something positive about the city. Even those who disagreed with him on most things saw him as a decent man whom it would be hard to dislike.

That’s not to say there were no complaints. One was that he never seemed to listen to criticism. Another was that he seemed more interested in PR and polishing his international reputation – or collecting social media “likes” – than in solving practical problems for London.

The second factor to Khan’s advantage is that he has reliable alibis for many of his most difficult problems. One is the tangle of ambiguities over who exactly is responsible for what. The ULEZ expansion is firmly associated with the Mayor, but there the consensus ends. If people are infuriated by a new local traffic scheme, housing development or planning decision – or wonder why nobody seems to take responsibility for Hammersmith Bridge – they often don’t know whether to blame the Mayor, TFL, local borough councillors or Whitehall. The other alibi is the Treasury. If crime is on the rise, is that because the Mayor has lost control or because the Tories nationally are failing to fund the police? It’s an argument that Londoners often sympathise with.

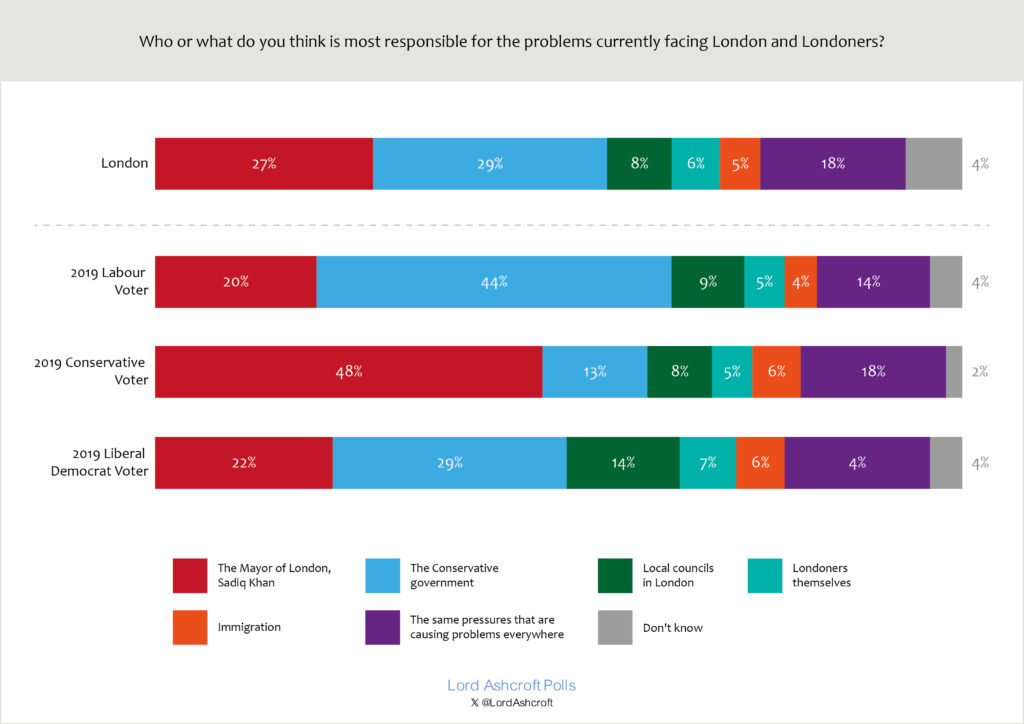

Overall, asked who they thought was most to blame for the problems facing London and Londoners, more blamed the Conservative government than Sadiq Khan, while just under one in five blamed the same pressures that are causing problems everywhere.

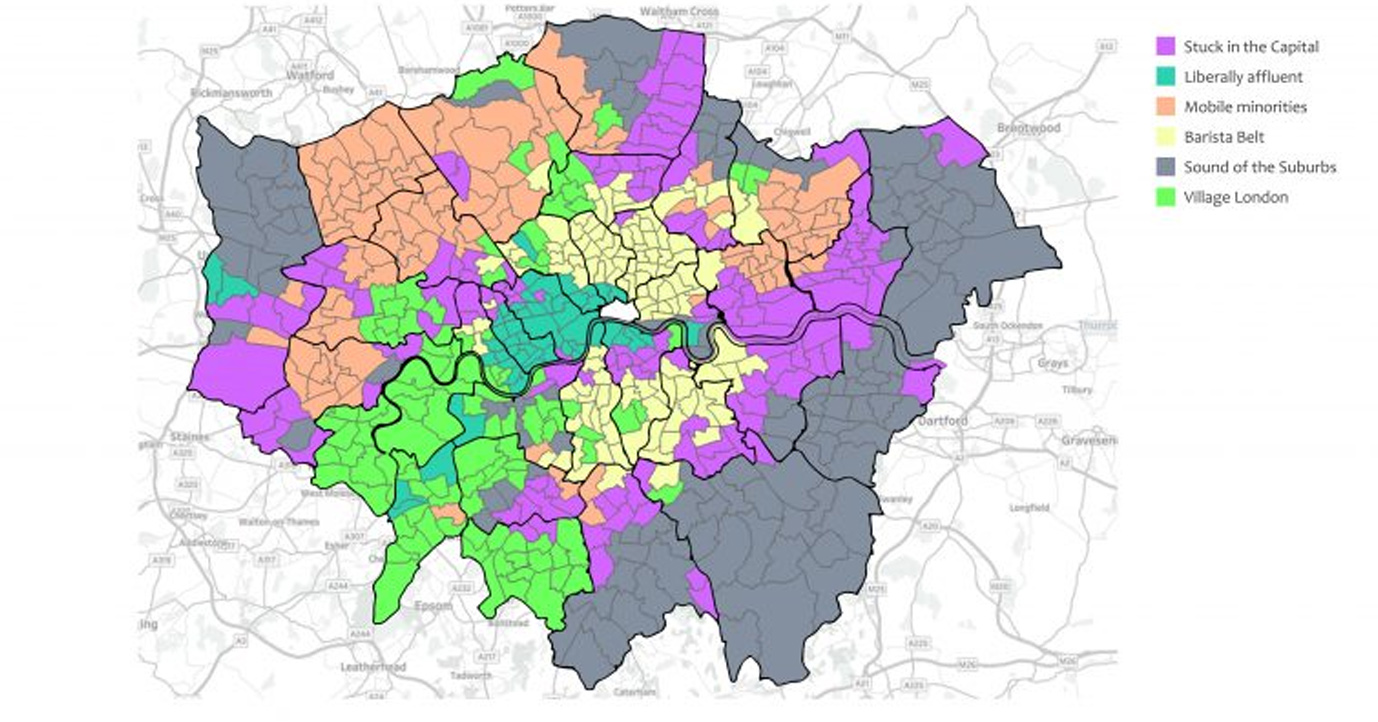

The third factor is that London is a hostile environment for Tory values at the best of times, and these are hardly that. From our parallel poll conducted throughout the country, we can see that Londoners are not more liberal or left-wing on everything – they are more likely to favour tax cuts, for example, and on average have similar attitudes to the debate on sex and gender identity. But on some issues – racism, Brexit, immigration and whether there is more in British history to be proud of or ashamed about – the balance of opinion is notably different. Londoners are less likely than most to describe themselves as British and, especially, English. And while people are prepared to look beyond party labels in Mayoral elections, the state of the Conservatives nationally is hardly an asset to Susan Hall, the party’s candidate.

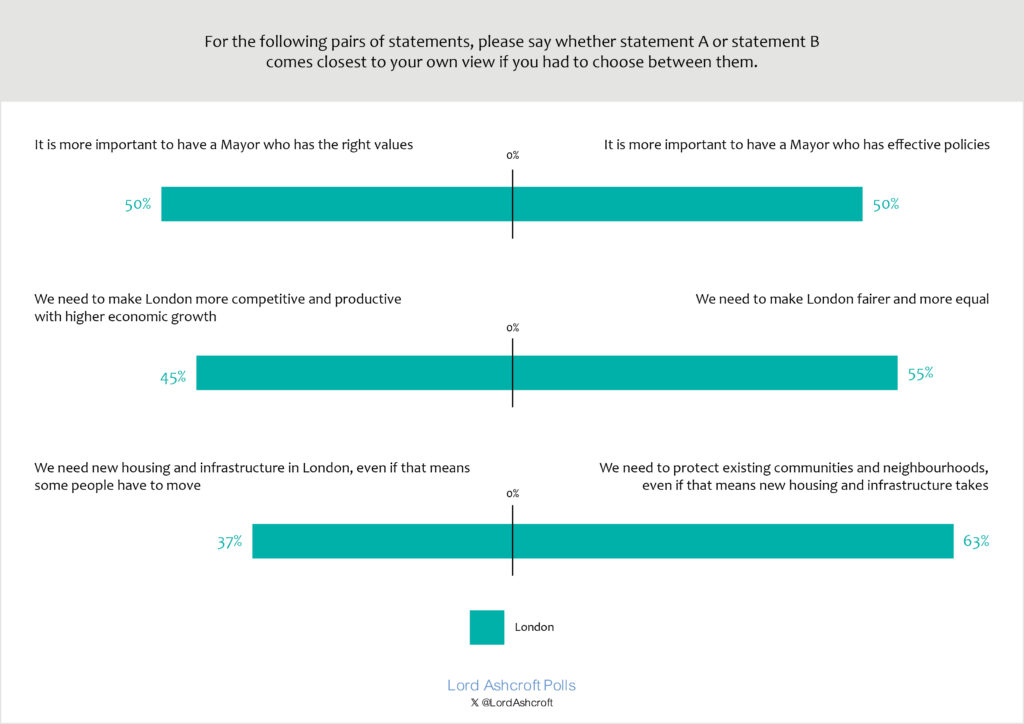

All this means that concrete improvements are only part of the story. We found Londoners evenly divided as to whether it was more important for the Mayor to have the right values, or to have effective policies – indeed for younger people and Labour-leaning voters, values had the edge. In this sense, what the Mayor is perhaps as important as what the Mayor does. While nearly half of London voters – including most Tories – want to make the capital more competitive and productive, with higher economic growth, a majority – including most Labour voters – think it’s more important to make London fairer and more equal. And supporters of different parties agree in similar proportions that protecting existing neighbourhoods and communities should take precedence over building new housing and infrastructure.

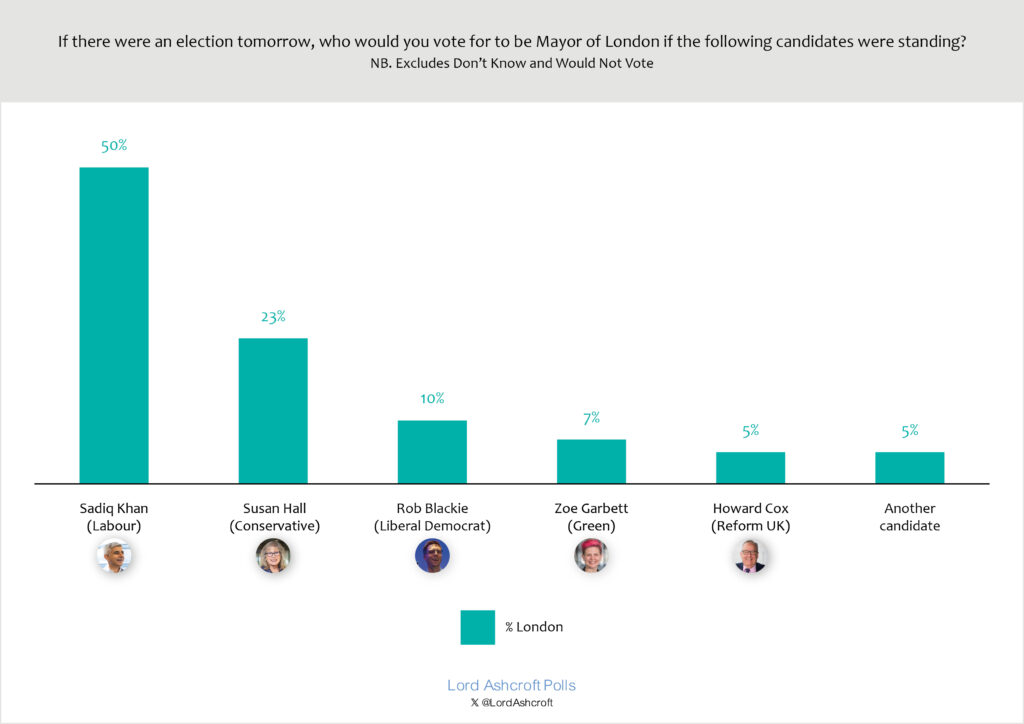

The upshot of all this is that, six months out, Khan leads Susan Hall by 50% to 23%, with the Greens and Lib Dems slugging it out for third place.

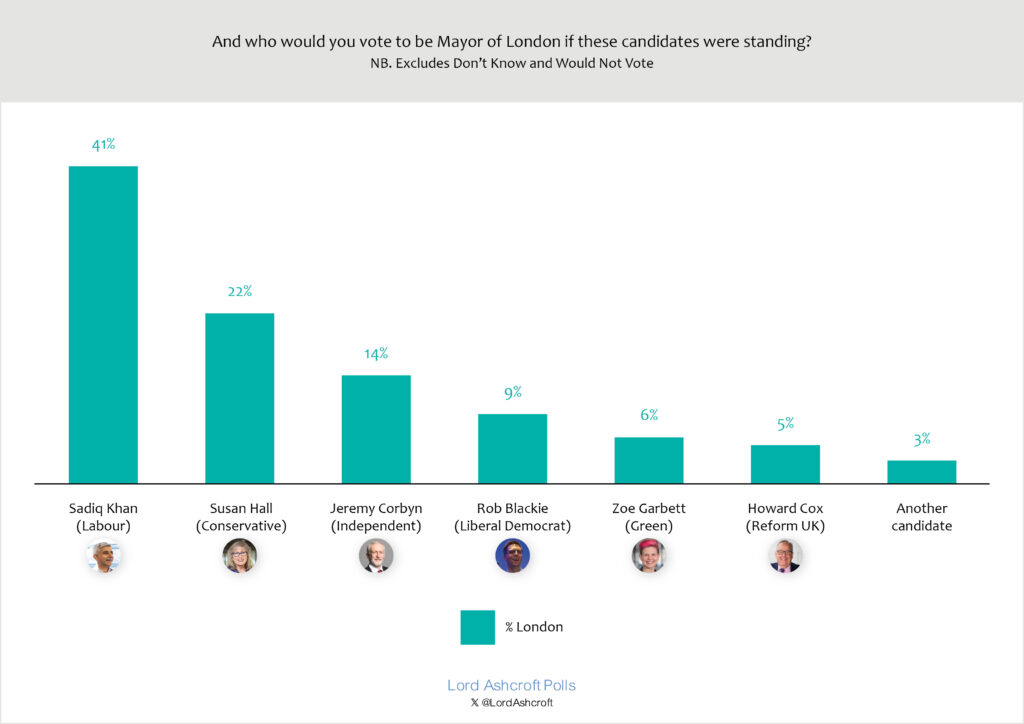

The picture does not change a great deal if Jeremy Corbyn enters the race. In our focus groups I found quite a lot of respect for Corbyn among London Labour supporters, though many of them hoped he would stay out of the contest and avoid splitting the party’s vote. Though just over one in five 2019 Labour voters said they would back him if he stood, we found Khan still ahead by 19 points in this scenario.

Things might well tighten before next May. The Mayoral election is hardly at the top of people’s minds, and it would be fair to say Susan Hall’s campaign has yet to break through in a big way, though I’m sure her team would say it’s still early days. In our groups, some had heard her name, and a few knew that she had promised to scrap the ULEZ expansion on day one if elected. Some had even seen clips of her in action at City Hall and thought she did a good job of trying to hold the Mayor to account. And there is still time for her to find a signature policy that captures Londoners’ imagination, or for Khan to get something badly wrong.

But the elements that came together to see a Conservative elected Mayor in 2008 – a national mood turning against Labour, a near-celebrity candidate in the as-yet-untarnished form of Boris Johnson, and a radical and increasingly unpopular incumbent – are not currently at hand.