This is an edited version of my presentation this week at the E2 Summit in Utah.

With just over a year to the next presidential election, Donald Trump has a commanding lead in Republican primary polls and Joe Biden insists he’s not going anywhere. How is it that, as things stand, the country is heading for a contest that hardly anyone seems to want? My latest research – a 20,000-sample poll together with focus groups in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Arizona – points us to the answer.

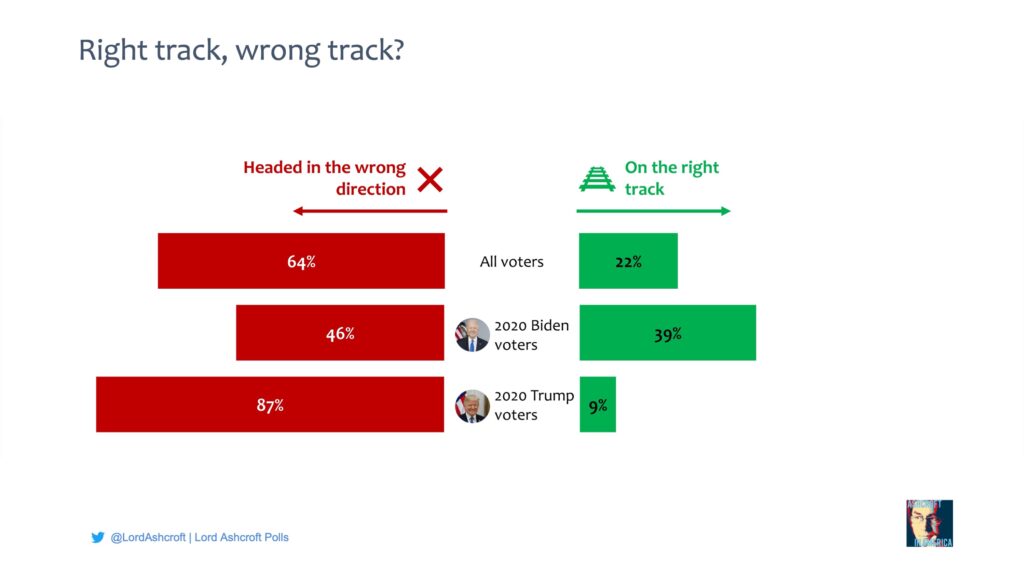

Overall, nearly two thirds of voters say the country is on the wrong track. Indeed, those who voted for President Biden in 2020 are more likely to say America is on the wrong track than the right one. As you would expect, their discontent takes many forms.

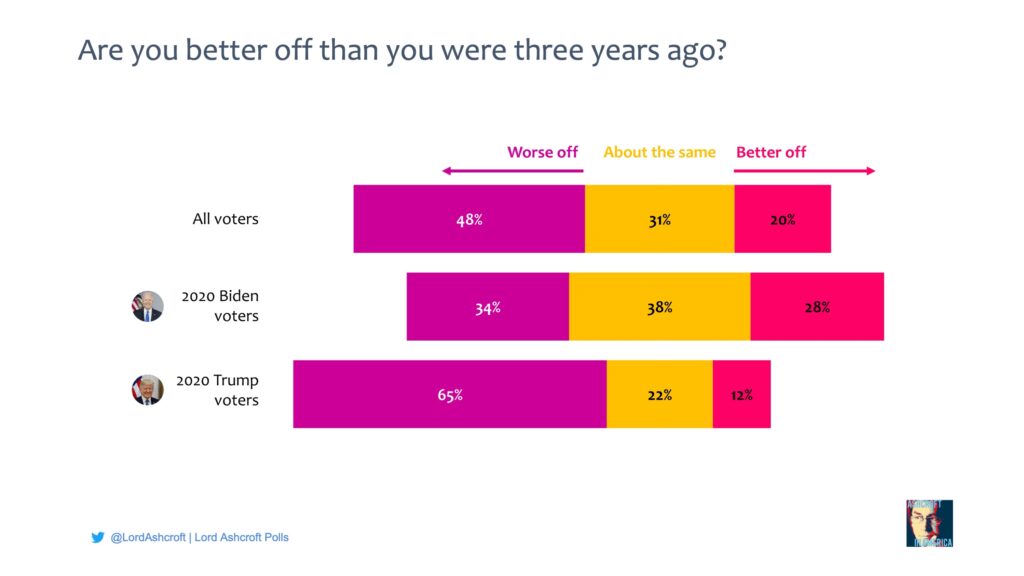

Crucially, few Americans say they are better off than they were three years ago. Biden voters are more likely to say they feel worse off since the president took office than the reverse. Most voters are also pessimistic about the outlook for the economy over the next year.

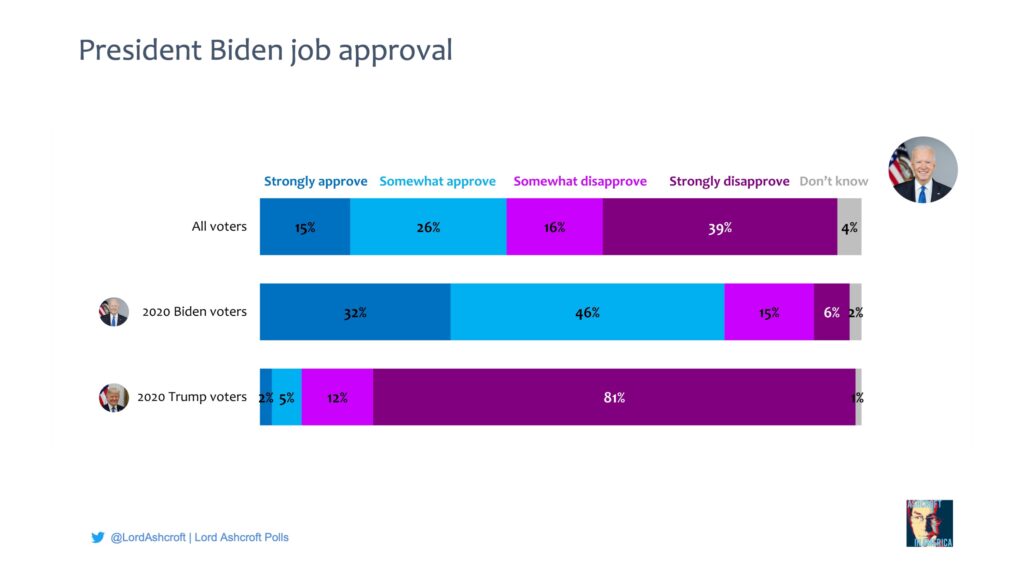

All of this is reflected in the president’s job approval. I found more than one in five of the president’s 2020 voters said they either somewhat or strongly disapproved of how he was handing his job. In our focus groups, Biden’s defenders pointed to infrastructure spending, student loan forgiveness and work to renegotiate Medicare drug prices. Critics talked about stagnant or falling living standards, counterproductive energy policies and – on the liberal side – excessive moderation.

Something both sides agreed on, ironically enough, was his failure to end division and rancour in political life. Here, Republicans pointed to an overly progressive liberal agenda and said they often kept their opinions to themselves for fear of being lectured or ostracised. They also said that reversing Trump initiatives like the pipeline on day one in office and calling his opponents’ supporters a threat to democracy were hardly the actions of a uniter. Democrats often blamed misinformation, which seemed to be code for the gullibility of Trump voters. Indeed it seemed that to them, division simply meant that the other side still refused to agree with them. But perhaps that is editorialising too much.

One thing that did unite voters was the condition of the president himself. His on-stage stumbles and rambling performances left many on both sides doubting that he was up to the job now, let alone how he would handle a second term. This in turn led people to wonder who was making the decisions – his aides, Kamala Harris, the DNC, or Dr Jill Biden?

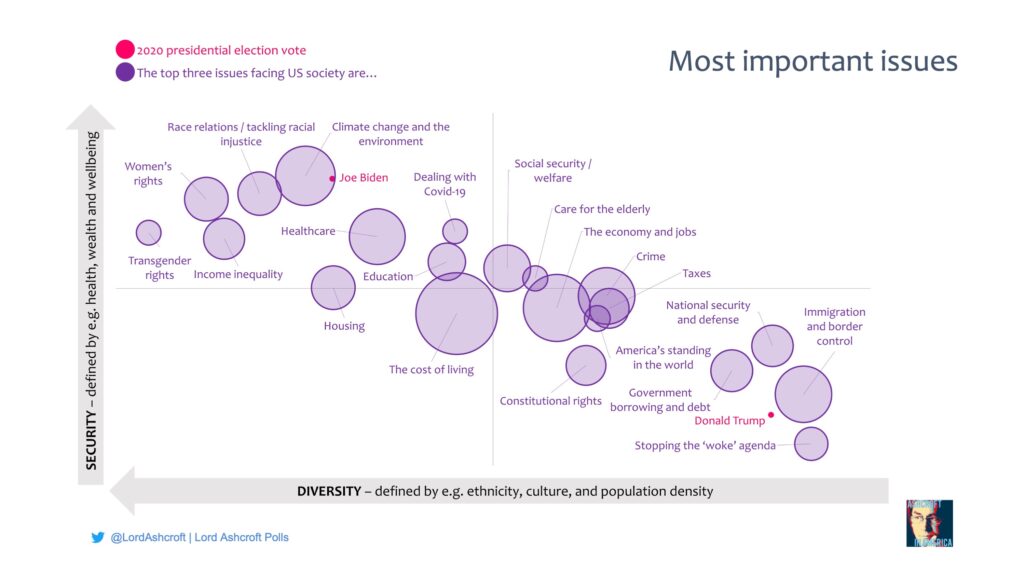

We see a very clear pattern when we ask people what they consider the most important issues facing the United States. The answers are plotted according to people’s security on the one hand – things like income, house value, education and health – and the diversity of their communities on the other – things like ethnicity and population density. The lower-diversity, lower-security bottom right – essentially, rural and small-town America that now constitutes the Republican heartland – is where we are most likely to find concerns about immigration and the border, national security, and the so-called ‘woke’ agenda. Those who prioritise transgender rights, climate change racial injustice are most likely to be in the more prosperous, diverse and politically liberal top left. The fact that the single biggest concern, the cost of living, is at the very centre of the chart shows it to be a universal worry not confined to any one part of the community.

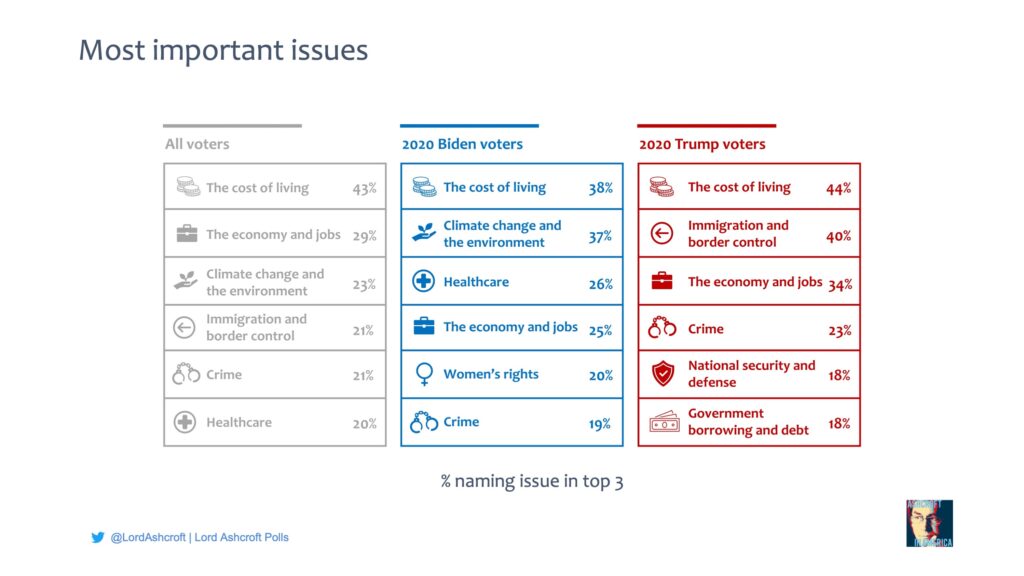

This is confirmed when we look at the issues of most concern to different kinds of voters. While the cost of living tops everyone’s list, for 2020 Biden voters this was followed by climate change and healthcare. For Trump voters, and incidentally for likely Republican primary voters, it was followed by immigration, with many on all sides believing the situation on the border is if anything worse than when Biden took office. The economy was next, followed by crime – which many on our groups had personally felt to be on the rise, including violent crime in previously peaceful places, as well as an epidemic of shoplifting.

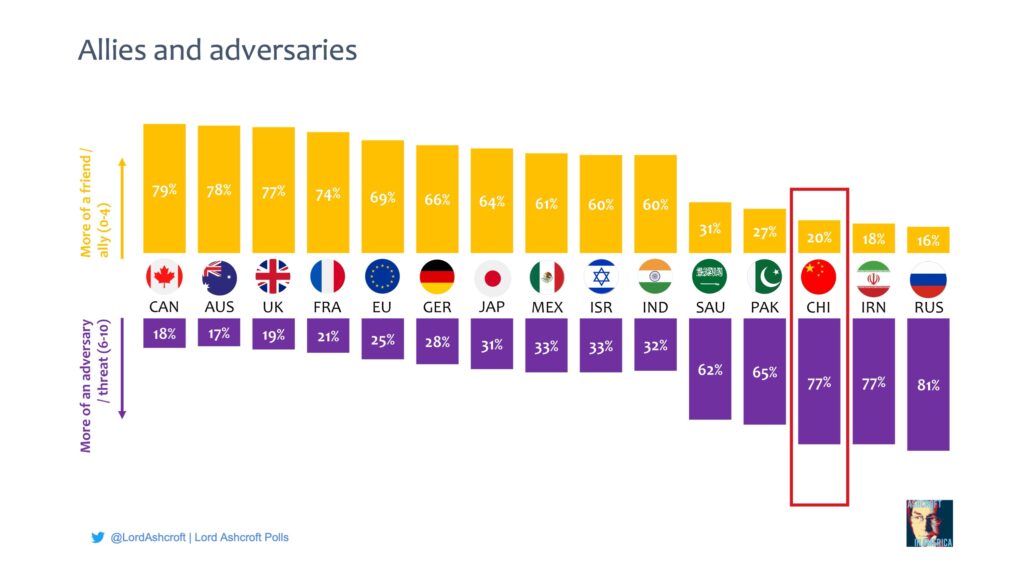

One issue on which political division is less evident is that of foreign relations, or more specifically, whether various countries are seen as allies or adversaries of the US. Most striking, I think, is the position of China, with 77% of Americans seeing the country as, to some degree, an adversary or threat – the same proportion as say the same for Iran.

In our focus groups, voters of all stripes saw China as an aggressive and untrustworthy competitor, if not actually an enemy. They saw China using its economic influence and technological capability to gain power around the globe, and lamented that the US had long ago made itself dependent on Chinese imports. Notably, people in all our destinations worried about China investing in land and property in the US – or as they nearly always put it, “buying American soil”.

Though many favoured a tougher approach to China, they wondered what this would mean in practice, given that – as a focus group participant succinctly explained – “we owe them a bunch of money. We don’t have that kind of leverage.” The only answer they could see was greater economic independence for the US, especially when it came to manufacturing. Many noted that this had been a big theme of Donald Trump’s presidency, and were not sure that such efforts were continuing under the current administration.

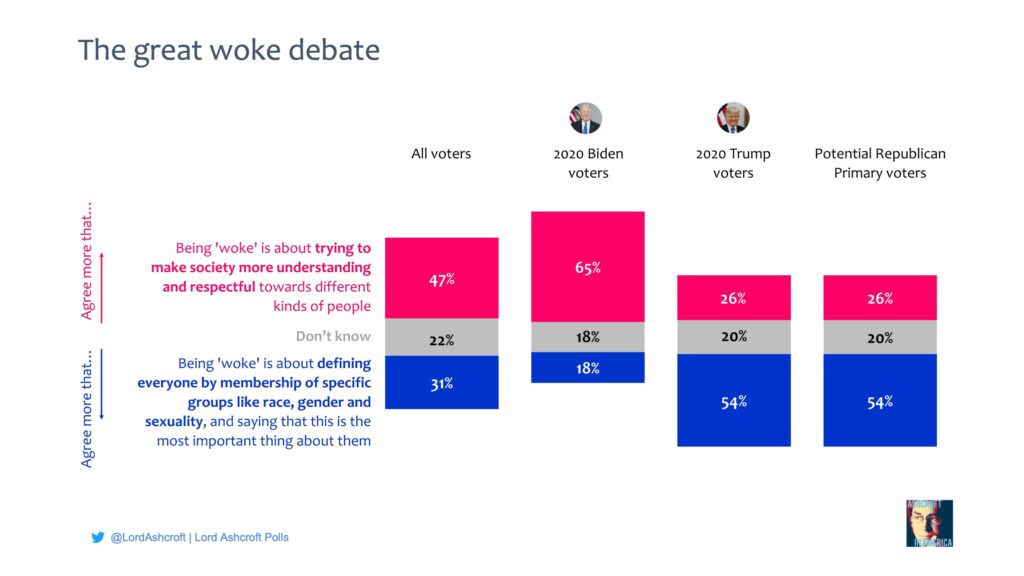

But if we’re looking for a really divisive issue, let’s look at the world of ‘woke’ – a term which has become ubiquitous without, it seems, ever being defined. For about half of voters – including about a quarter of Republicans – being ‘woke’ is a positive thing, to do with trying to make society more understanding and respectful towards different kinds of people. But for most on the right, it is a damaging part of identity politics.

I found that some things described as ‘woke’ – such as mandatory diversity training or ESG investing by state bodies – are treated with broad acceptance or indifference, and draw only muted resistance from the Republican side. Others are more contentious, especially things like trans athletes in women’s sport and access to single-sex spaces. Essentially, corporations can go woke and go broke if they want to, but personal and parental issues are different.

Potential Republican primary voters in our focus groups had strong views on many of these questions – but that is not to say they want to see them at the forefront of political debate. They want politics to be about the bread-and-butter issues, not furious rows about culture and identity. My sense is that they want a candidate whose judgment they can trust if these things cross his or her desk, but they don’t want to see them front and centre in anyone’s campaign.

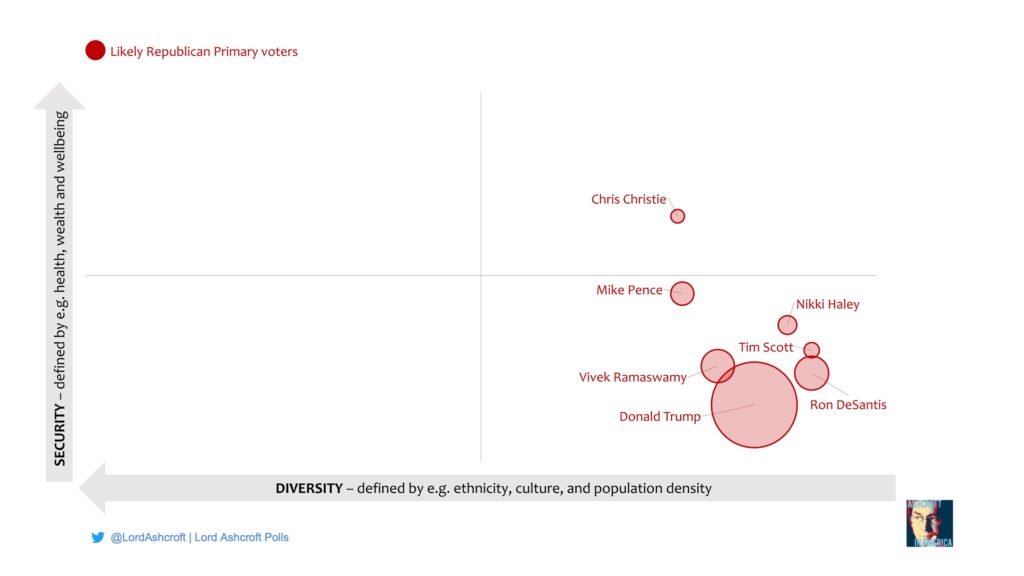

And so to the election. In our polling of likely Republican primary voters we found the familiar pattern that you will have seen in published polls – with Trump on something over half the vote, and Ramaswamy, DeSantis, Haley and Pence within a few points of each other. Perhaps more interestingly, the combination of our sample size and the demographic map lets us visualise where the more prominent candidates are drawing their support. Notably, those supporting Vivek Ramaswamy and Ron DeSantis are most likely to be found in Trump territory, demographically speaking. Those supporting Chris Christie are furthest from what is now the centre of gravity of Republican support.

As you will have noticed, all of this is overshadowed by various legal proceedings. Most Republicans and a good number of Democrats think the lawsuits against the former president are politically motivated – though this often means that while the charges would never have been brought against a defendant not called Donald J. Trump, that doesn’t necessarily mean there is no case to answer. Likely Republican primary voters also say the indictments make them more rather than less inclined to support him, and will help rather than hinder his chances of victory.

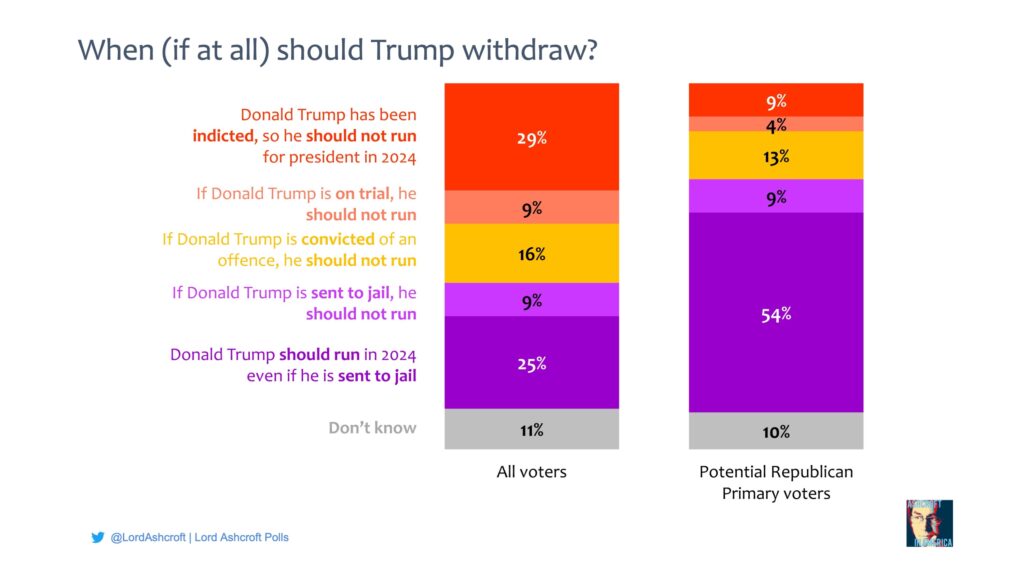

But at what point do people say enough is enough? Fewer than one in ten primary voters say the indictments are reason enough for him not to run. A further 28% say he should withdraw if he is on trial, convicted or imprisoned during the campaign. But more than half told us he should continue to run even if he is sent to jail.

These numbers are pretty stark, but my sense from the focus groups is that even if they think the charges are political, for Trump to be convicted by a jury would prompt considerable soul searching among his potential supporters.

Listening to voters in our groups talk about why they were backing Trump again, it was clear that we are not looking at a personality cult, as many assume. As in 2016 and 2020, they know his flaws but see someone who will act on the things they care about and defend their values, even if he doesn’t exactly embody them. They like that he “demands the room” in a way no other candidate they have seen yet does. When it comes to choosing an effective advocate for their interests, as one put it, “nobody does Trump as well as Trump does.” They also see him as the Republican most likely to beat the Democrats next November.

Here is what our focus groups had to say about the other candidates.

Vivek Ramaswamy had certainly caught people’s attention, and many said they wanted to hear more about his ideas. Educated, articulate, successful and an outsider, he was well-presented and polished, though a bit too over-rehearsed for some – a voter in New Hampshire said it “seemed like everything he said was practised in the bathroom mirror.” Many drew parallels with what we might call Early Trump. As a woman in Cedar Rapids put it, “he’s batshit crazy but he’s fun to watch.” Some thought the Trump parallels were very deliberate, leading them to wonder how far he himself believed what he said. Several concluded he was setting himself up for future campaigns, or aiming to win Trump’s favour for the VP position.

Ron DeSantis also had a number of supporters in our groups but there was a feeling that things had taken a wrong turn somewhere. People often remarked on the difference between Governor DeSantis – the accomplished leader who stood up to Disney, guided Florida through covid and, more recently, managed an impressive response to Hurricane Idalia – and Candidate DeSantis, who seems to many to be trying too hard to be the new Trump, going out of his way to create controversy, and therefore struggles to project an authentic persona or settle on a clear message. As someone in our Charleston groups asked, “What are you really about?”

Many were impressed with Nikki Haley’s first debate performance, saying she came across as tough and smart and was able to make her points strongly in a crowded field. They note that she managed to emerge from the Trump administration without baggage, and often see her as a conservative realist. People like her foreign policy experience, particularly her stance on China, and often suggest her level-headedness and diplomatic skills would make her an excellent running mate and vice president in a second Trump term. “She’s got global diplomacy – she would balance Trump and keep him on track,” as an Iowa voter put it. Circular though it may be, the recurring doubt is whether she will garner enough support to make her worth supporting.

Mike Pence is between a rock and a hard place. Many who respect him for doing his duty and certifying the election don’t like the fact that he was part of Trump World for so long, while diehard Trumpers wish he’d stuck it out for longer. Still, people recognise his moral compass. But they wonder why exactly he is running. Even his admirers doubt that his very conservative views would win over the national electorate, and they assume he must know this too. A widespread theory is that the former vice president is running to seal a legacy independent from that of Donald Trump, and “just wants to say his piece”.

Chris Christie’s colourful time as governor of New Jersey is often recalled with a smile, and people often say, “do you remember the thing with the bridge?” His vocal opposition to Donald Trump plays better with Democrats and Independents than with Republicans, though people have noted his changes of heart on the question. Many think his campaign seems more of an expression of rage against Trump than a serious play for the White House – or as we heard in South Carolina, “he’s just out to cause trouble.”

Tim Scott was variously described as likeable, honest, a straight shooter and a really great guy, which are not things you hear every day in political research. People respect his story and his background growing up in North Charleston. Some feared he was almost too decent, noting that he seemed quiet in the first debate, and most doubted that he would ultimately be the contender. More than once we heard “I like Tim Scott, but he’s too damn nice.”

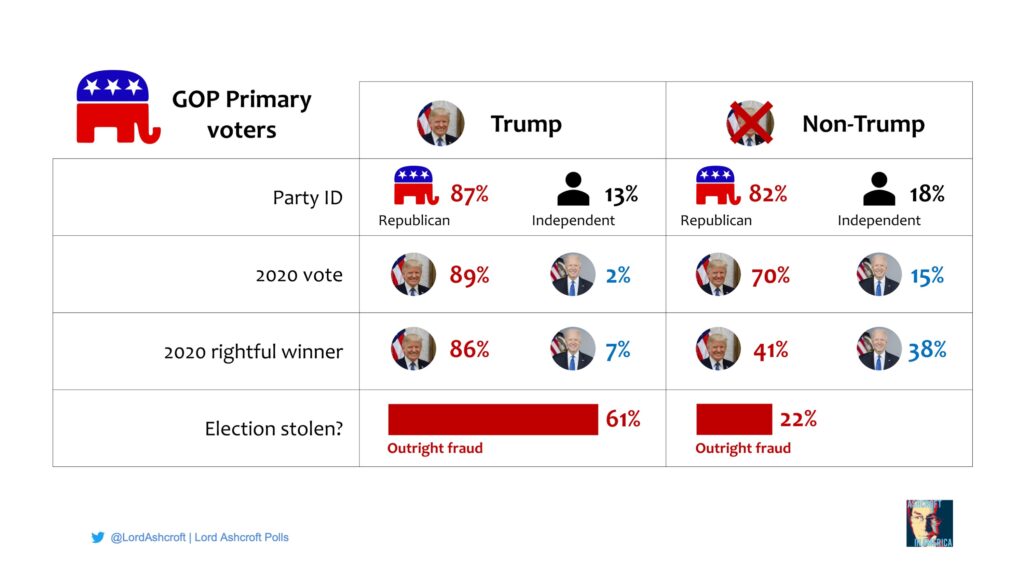

The size of our poll enabled us to look at the differences between likely Trump and non-Trump primary voters.

On most issues – priorities for government, wokeness, foreign affairs, immigration, energy policy – there is little to choose between the two groups. But a few points of difference stand out.

Most striking is that fewer than half of non-Trump primary voters say that Trump was the rightful winner of the 2020 election, compared to 86% of those backing the former president. Trump voters are also nearly three times as likely as their non-Trump counterparts to say that the official result is down to outright fraud, rather than the Democrats simply benefiting from new rules on things like absentee ballots.

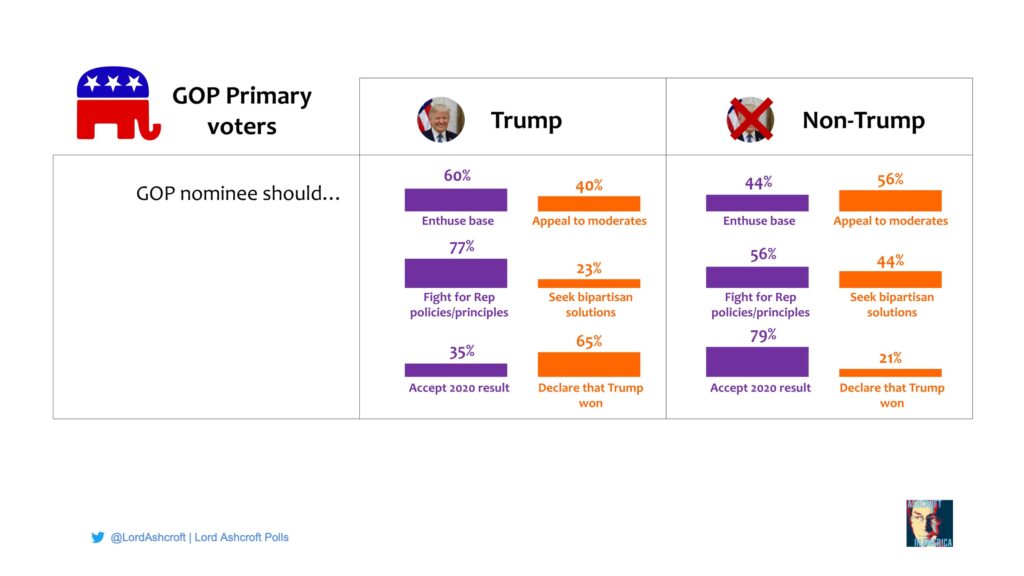

The two groups also diverge slightly when it comes to the kind of candidate and campaign they want to see. While most Trump supporters think the priority at the general election is to enthuse the Republican base, non-Trump voters see more of a need to appeal to independents and 2020 Biden voters. While more than three quarters of Trump voters want a candidate who will fight for Republican policies and principles, nearly half of his challengers’ voters want a nominee willing to work with opponents and seek bipartisan solutions. And while most Trump voters stick to the idea that their man was robbed in 2020, non-Trump primary voters overwhelmingly think it’s time to accept that result and move on (though in my groups, even his supporters wanted him to shut up about the last election and concentrate on the next one).

Many of those backing non-Trump candidates were suffering from Trump fatigue, or more to the point, thought the condition so widespread in the country that having Trump as the nominee would cost them the chance to dislodge the Democrats from the White House.

However, they were rarely devoted to any one of the challengers. Although the choice was in their hands, they were almost waiting to see who would emerge from the pack and prove themselves a winner. My sense is that if and when one of them does so – and if it happens in time – they could start to ascend in the polls quite quickly.

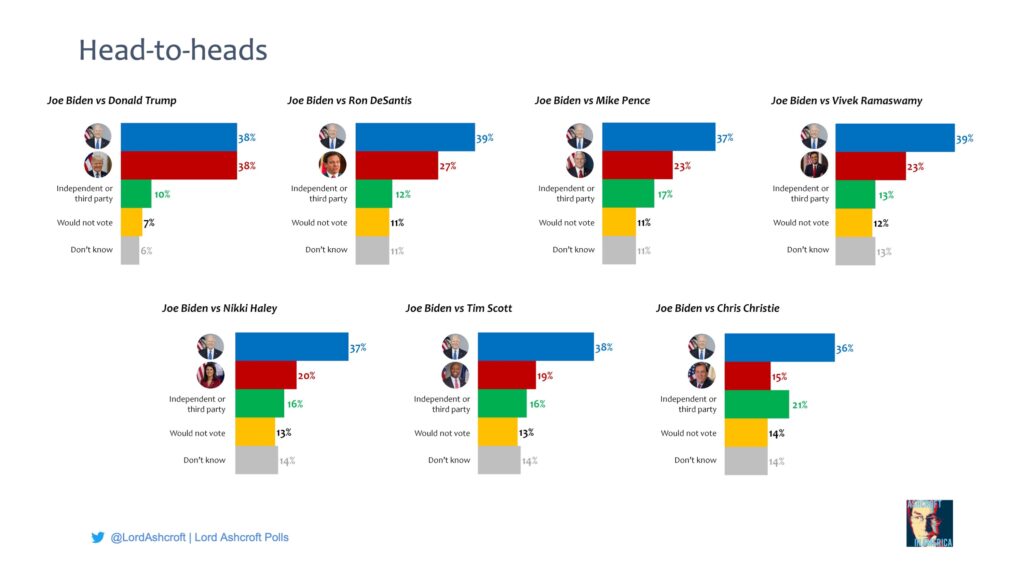

Polls about hypothetical nominees should be taken with an even bigger pinch of salt than other surveys about voting intention in a distant election, but we asked the question anyway. At first glance, this seems to suggest that Biden would beat any Republican other than Trump, but I think there are two more important points.

The first is that this is still largely a matter of name recognition. Those of us who spend more time following politics than is good for us can sometimes forget that most people have better things to do. A participant in one of our focus groups voters told us he liked what he’d seen of that Ron DeShwami, he sounded really interesting.

I also think the apparent ceiling on the Biden vote is more telling than the margin between him and his putative opponents. With Biden and Trump the only known quantities in terms of an actual presidency, in none of these scenarios does the president reach even 40% of the vote. Except for the Trump-Biden rematch, our data shows 2020 Trump voters to be much more likely than 2020 Biden voters to say they don’t know how they will vote, or to take refuge in the third-party option. This is ominous for the Democrats, since it means there is much more room for Republicans to swing behind their eventual nominee than there is for Biden to expand his support.

This, of course, assumes that Biden will be on the ticket.

If, for any reason, a vacancy should arise, most assume it would be filled by Kamala Harris – though few relish the prospect, even among Democrat supporters.

Most agree that the vice president seems to have been kept out of the public eye – either because of her eccentric public performances or in order to dispel the idea of a potential rival to Joe Biden. African-Americans in our groups complained that she was put on the ticket to secure the black vote but then disappeared from view. Some recall that she was given responsibility for the southern border but has not made a notable success of the project. Even the most sympathetic saw her as a less likely election winner than Biden, even if only because they assume too many Americans would refuse to vote for a woman of colour. Few saw much prospect of a Democrat other than Biden keeping the White House in Democrat hands.

So where does this leave us? Though the circumstances are different, in some ways this election feels eerily reminiscent of 2016. Trump supporters are determined, but it is as hard to find enthusiasts for Joe Biden as it was for Hillary Clinton seven years ago.

And we’ve seen how for many Trump voters, their support is a transaction, as it always was: they put up with the parts they don’t like in order to get the things they want – whether that’s a stronger economy, a healthy 401k, a realistic energy policy, a counter to the identitarian agenda of the left, or dare I say it, the chance to make America great again. This includes voters who are thinking of switching back from Biden to Trump, some of whom we found in our groups. It would be fair to say that some of them have decided that, on reflection, nasty tweets were less bad than five-dollar gas.

Democrats often condemn people for making this calculation, but their vote is a transaction too, as it was in 2020: for them, Joe Biden was and is the means to an end – that of stopping Donald Trump. Few of them actively want Biden or Harris, but they like to boast that their vote is “a chess piece, not a Valentine.” In other words, we have another of those irregular verbs you find so often in politics: when it comes to voting, he is selfish, you are transactional, but I am strategic. And therein lies the explanation of why we are heading for the rematch that everyone seems to dread. You might almost call it The Art of the Deal.