“Britain is broken – people are getting poorer, nothing seems to work properly, and we need big changes to the way the country works, whichever party is in government.” In my latest polling, an extraordinary 72% agreed with this statement, including more than half of 2019 Conservative voters. Only just over one in five opted took the alternative view that “there will always be problems that need sorting out, but there is nothing fundamentally wrong with the way the country works.”

Many thinkers of various stripes agree: economists, including those on the Growth Commission established by Liz Truss, consider the urgent question of how to improve Britain’s sluggish productivity. Many others on the centre-right – not least those contributing to ConHome’s project on reducing demand for government – worry about an allied problem: that the state itself has become too big, expensive and burdensome, and that the Tories should make it their mission to rein it in.

This is a recurring theme in Conservative thought, and with good reason. But it’s easy to take the arguments for a smaller state for granted, and assume they are self-evident to everyone. At least as dangerous, politically, is the temptation to think in terms of theory when voters think almost exclusively in terms of practice. I therefore wanted to find out how people saw the questions at stake in this debate – about the tax burden, business regulation, spending and public services, the role of the state itself, and how they reacted to the low-tax, small-state agenda.

Help or hindrance?

In his political masterpiece Parliament of Whores, PJ O’Rourke gave one section the stirring title “Our Government: What The F*** Do They Do All Day And Why Does It Cost So Goddamned Much Money?” It is an attitude familiar on the centre-right, and has its merits. But as my research confirmed in various ways, most voters, including a significant chunk of Tories, do not see government primarily as an expensive nuisance.

I found voters overall with a more positive view of government than they had of capitalism and (even among 2019 Tories) big businesses. Regulations on business were also seen in a generally positive light – slightly more so, among voters overall, than free markets.

More than two thirds agreed that “people have a right to things like decent housing, healthcare, education and enough to live on, and the government has a responsibility to make sure everyone has them”; only a quarter preferred the statement “people should provide for themselves and not expect the government to provide for them.”

Similarly, people were nearly twice as likely to think that “government should help people out when they’re struggling” as to think “people should provide for themselves and be responsible for their own decisions” – though there was much less support for the idea that government should “protect people from making bad choices”.

We also saw how people look to the government to ensure a degree of what they regard as fairness in economic life. Less than a quarter agreed it was more important that the economy grows faster in the long term, “even if the divisions between rich and poor grow larger in the short term”. A clear majority, including 43% of 2019 Tories, agreed it was more important that such divisions are reduced “even if that means the national economy grows more slowly in the long term.”

Indeed, people were closely divided over the effects of economic growth itself. Less than half (48%) agreed that growth meant “more jobs and more money for public services, so everybody benefits”; almost as many felt that “only the people already doing well seem to benefit” when the economy grows.

This theme of fairness played an important part in people’s perceptions. Voters overall were more likely to say fairness meant “people getting what they deserve” (51%) than “making sure everyone gets the same share” (39%). However, but many thought things were increasingly skewed against those who worked and saved and tried to be responsible with their money, or resented that they as contributors were missing out on what they saw as generous state provision that was made to people who did not seem to want to work.

On the cost of living, two thirds of voters, including 43% of 2019 Tories, thought the government could do more to help but was choosing not to. Even though most blamed companies for putting up prices to boost their own profits, over and above increases in their own costs (64%, including majorities of all parties’ supporters), many in our focus groups felt it was the government’s job to do something about the problem – whether through direct help to consumers or by somehow compelling businesses to behave differently.

This may help to explain why clear majorities, including most 2019 Tories, thought the government ought to control the water, rail, electricity and gas industries. When we asked why, the most popular answers were that national ownership would mean more investment, better service and lower charges, and the principle that important services should belong to the people not private companies.

Spending and public services

Nearly half of all respondents thought spending on public services had gone down over the last 10 years, and three quarters thought they had deteriorated over that time. Less than a quarter (23%) thought spending had risen (including only 38% of 2019 Tories) and only 3 in 100 thought services had improved.

This helps explain why, in a separate question on whether domestic spending in various areas should rise, stay the same or fall, people wanted to see increases in nearly all areas – especially in health and social care, schools, the state pension and help with bills during the cost-of-living crisis.

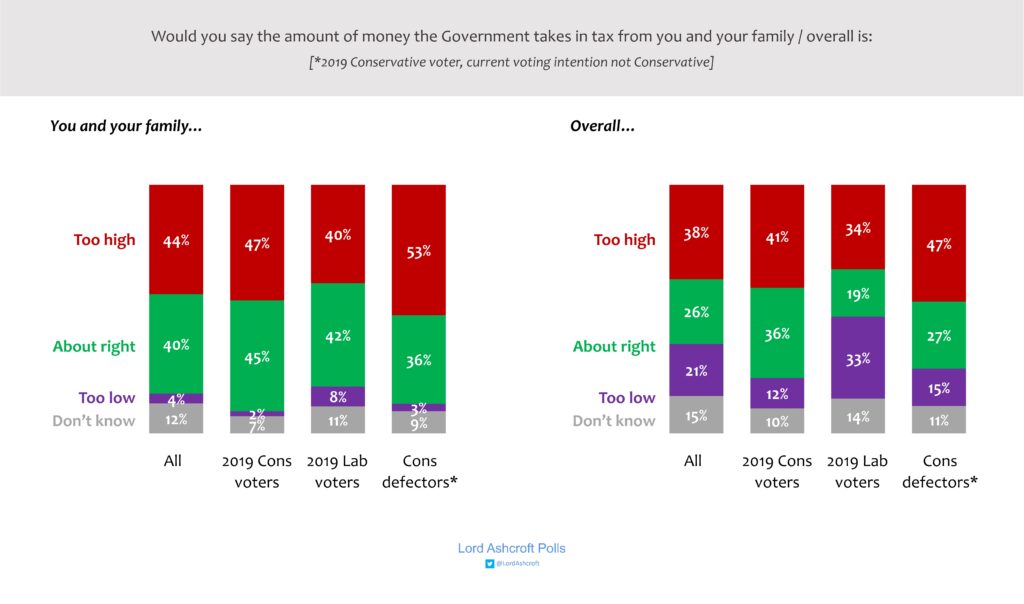

At the same time, just under half of all voters (44%) thought the amount of tax they paid was too high (eleven times the proportion who thought it was too low), though only 38% thought this was true of the amount of tax the government takes overall.

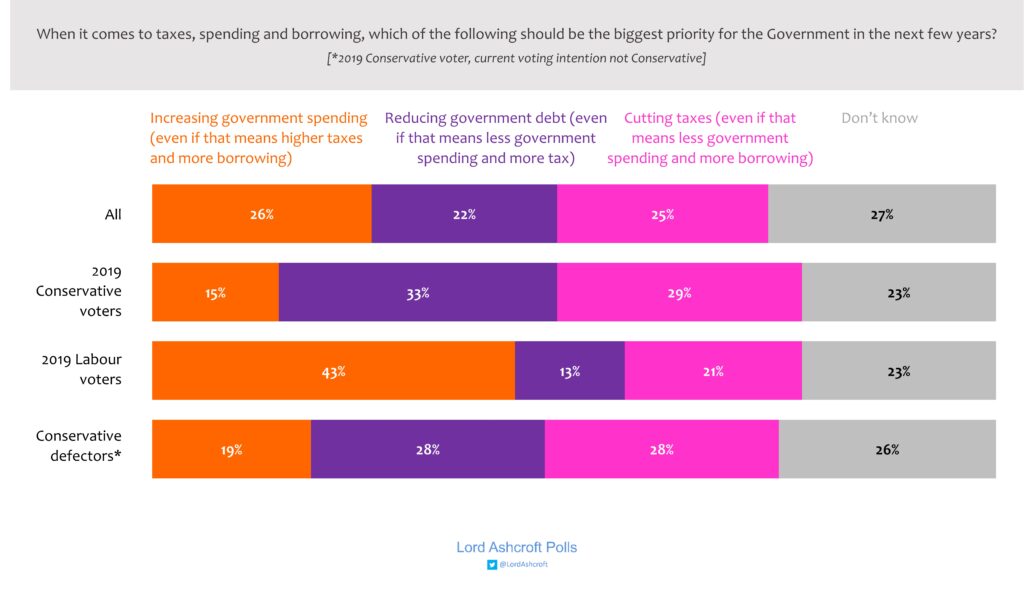

Asked whether the government’s priority should be to increase spending, reduce debt or cut taxes, people were unhelpfully almost evenly divided between the three, with just over a quarter saying they didn’t know.

There was a marked difference between political groups, however. One in three 2019 Conservatives prioritised reducing debt, compared to just 13% of Labour voters, while 43% of Labour voters wanted prioritised higher spending, compared to 15% of 2019 Conservatives.

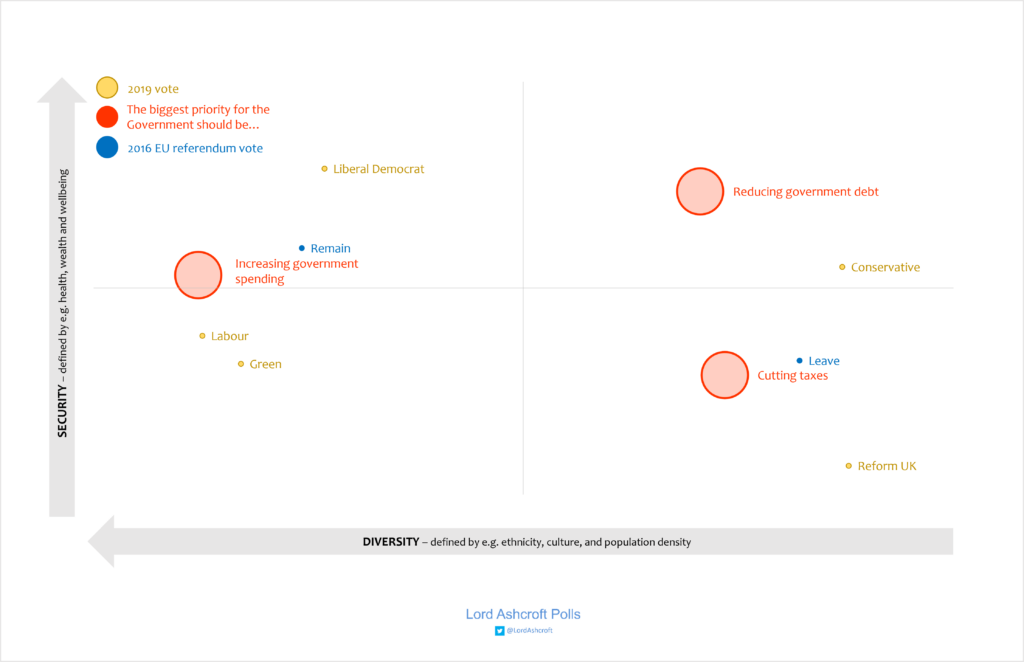

Our political map shows how different issues, attributes, personalities and opinions interact with one another. The closer the plot points are to each other, the more closely related they are. Here we see how the three fiscal priorities appeal to different parts of the electorate. Those who want to see higher spending are most likely to be found in Labour-Remain-Lib Dem territory, as might be expected. On the other side we see two poles of competing priorities in 2019 Conservative-voting territory. Those wanting to reduce debt are firmly in the more prosperous and secure top-right quadrant, while those wanting to see tax cuts prioritised are in the less secure, largely Leave-voting bottom right.

Small state, happy state?

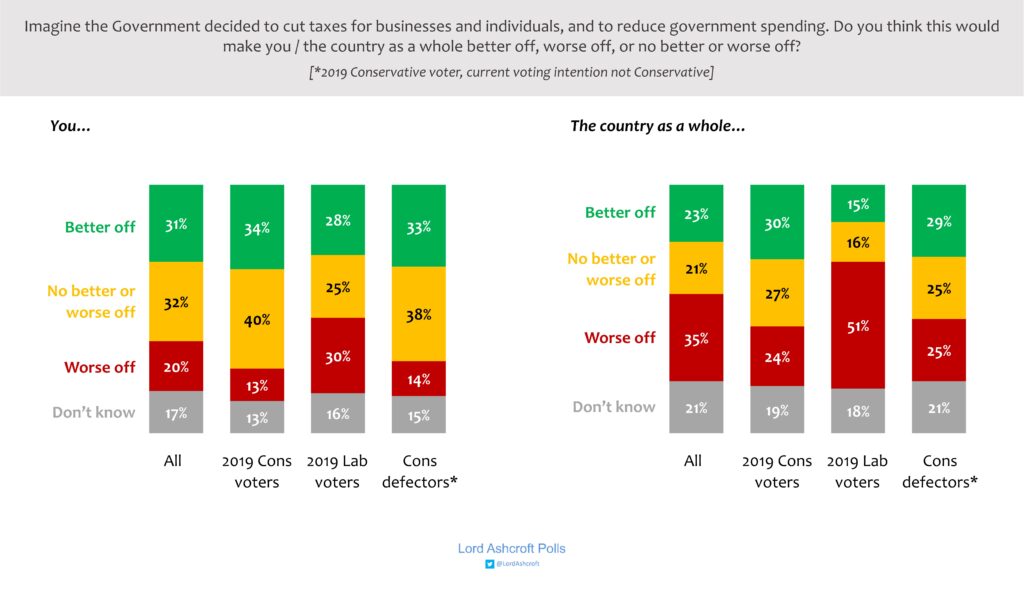

We asked people to imagine that the government decided to cut both spending and taxes, and whether they thought this would leave them – and the country as a whole – better or worse off.

Only 31% thought they personally would be better off, though this was more than thought the same would be true of the country as a whole (23%). Just over one third thought the country would be worse off, though only 1 in 5 (20%) thought they would be worse off personally.

In our focus groups, some accepted the idea in principle that a smaller state that taxed less might be able to do the things it focused on more effectively. However, they struggled to think of things the state currently did that it could stop doing or leave to individuals or non-state bodies. People also reasoned that these things would still have to be paid for, even if not out of taxes, leaving them no better off.

More often, people thought the problem was that the state did things badly or that essential services like health, schools and the police were underfunded. They tended to conclude that it ought to be doing more, not less (“what, even less?”, as a woman in Walsall put it incredulously). Others noted that with current levels of borrowing and debt, significant tax cuts were simply unrealistic.

When we presented our poll respondents with various arguments for low taxes and asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with each one, the most popular were the statements “the more tax companies have to pay, the more they will put their prices up,” that “the government can’t be trusted to spend taxpayers’ money effectively” whichever party is in power, and “I know how to spend my money better than the government” – though in each case more said they “somewhat” agreed than did so “strongly”.

Other statements commanding majority agreement were “lower taxes give people and families more freedom and control over their lives,” “the government takes too much of what people earn – it should let them keep more of it,” and “higher taxes will mean less incentive for people to start a new business” (though only 18% agreed strongly with this statement).

People were somewhat less convinced by the arguments that lower taxes would attract more overseas investment; would prompt UK companies to invest more in research, equipment and technology; would mean more prosperity for everyone; would significantly reduce the cost of living; and that higher business taxes will mean fewer new jobs and lower pay for staff.

More disagreed than agreed with the propositions “countries with higher taxes tend to be worse off” (with 40% saying they didn’t know), “the more businesses have to pay, the less the economy will grow and the less money there will be to spend for everyone,” and “cutting taxes will mean less money for public services.”

My full report, The State We’re In, is available along with the detailed polling data at LordAshcroftPolls.com. Some of the things we found would probably have small-state advocates shaking their heads in despair. This, though, is the prism of opinion through which any programme to roll back the state would be seen. Yes, the state is too big and needs to work better. But even if people find government unreliable, inefficient and expensive, few will vote for less of it as an end in itself.