This article was first published in the Mail on Sunday.

After 13 years of Conservative government, things were not supposed to look like this. Strikes, inflation, record NHS waiting lists, a sluggish economy and apparently uncontrollable migration point to a country where things are going wrong. Covid and Ukraine sound increasingly like excuses, not explanations.

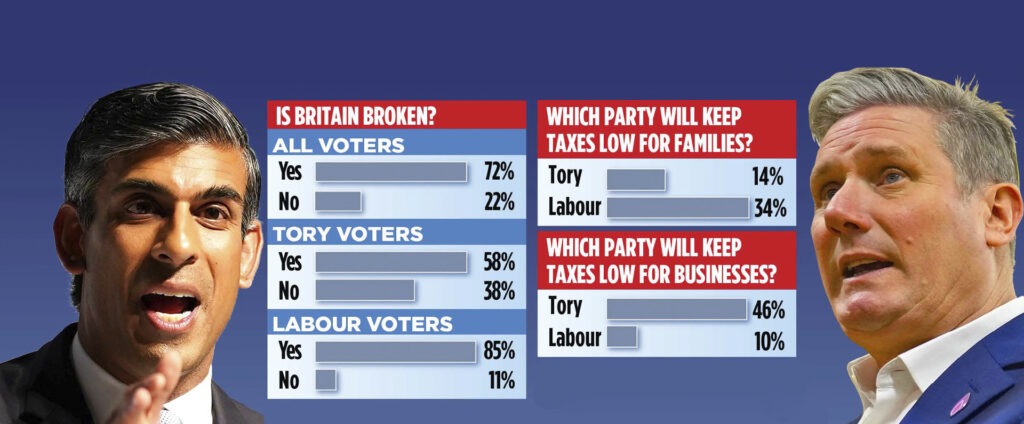

But people sense more than an administration running out of steam after a bruising stint in office. I found more than seven in ten agreeing that Britain is broken and needs big changes, whichever party is in charge.

Political and economic sages debate how to boost the dismal rates of productivity that hold the country back compared to its more prosperous peers. For many Conservative thinkers, pondering the party’s direction in a new term of government (or, as many expect, in opposition), the problem is the state itself. Recent Tory governments – prompted by Covid and a desire to show suspicious voters that austerity was over – have spent, taxed and borrowed at a rate that would have made Gordon Brown blush; these critics argue that government has grown too big, tries to do too much, and so imposes an excessive burden on business, workers and families.

There is a lot to be said for this view: allowing governments to consume ever more of our national income is a recipe for economic and social decline. But as Mrs. Thatcher’s Tories understood in 1979, any attempt to reverse the trend has to start not with economic theory, but with people.

Talking about their goals in life – owning a home, seeing their children do well, retiring comfortably at a time of their choosing, living a healthy life – voters tend to see government as a potential source of help, albeit an unreliable one, not an obstacle. Two thirds say the government could do more to assist with the cost of living, but is choosing not to. Similar proportions say it’s the government’s responsibility to ensure people have decent housing, healthcare, education and enough to live on. Less than a quarter believe spending on public services has risen in the last decade, and only three in a hundred say those services have improved – hardly the ideal context in which to argue it is spending too much.

And though people doubt politicians’ motives and competence, they harbour similar suspicions of the private sector. Most think companies have raised their prices to boost profits, over and above increases in their own costs. Voters overall are even less positive about capitalism and big businesses than they are about government. Many are suspicious of greater private involvement in delivering public services, even though they recognise such services are badly managed and inefficient. They see business regulation as a force for good, and are divided over new oil and gas production and the idea that major infrastructure projects should be pushed through faster. Clear majorities, even among Tory voters, say the government should own the water, electricity, gas and rail industries, believing the result would be more investment, better services and lower charges. Only just under half say economic growth means more prosperity all round; almost as many think that those already doing well seem to benefit.

Of course, people think things could be vastly improved. We heard some hair-raising examples of public sector profligacy from our focus group participants, especially those working in the NHS or firms contracting to it. Nor, to put it mildly, did we find an appetite for paying even more tax. Voters were eleven times as likely to feel they paid too much tax as too little, and while some said they would be happy to pay more if they thought services would improve as a result, few thought this would happen in practice.

What they did feel, very strongly, was a fraying relationship between what they put in and what they got out – or more to the point, what other people seemed to get out. Many complained that it was impossible to find recruits for reasonably paid jobs or that those who chose not to work seemed to live as comfortably as they did. Some, worried about losing the family home to pay for care, wondered why they had bothered with the “hamster wheel” of mortgages and savings. Many feel that the problem with Britain is that we no longer manufacture things, that we are too reliant on imported goods, energy, food and technology, and that our workforce lacks drive.

But few voters conclude from all this that the answer is for the state to do less (“what, even less?” as a woman in Walsall put it). It was telling that they saw the generous furlough scheme as one of the few bright spots in the Tories’ record – though even this was criticised by some as partly wasteful, ill-targeted and something the whole country was now paying for. While arguments for lower taxes are appealing, in practice even many Tory voters are nervous about the idea of rolling back the state. If the government stopped doing things, they say, who would do them instead? Few want us to become more like the USA, land of rugged individualism.

Many Tories might wish people felt differently about some of these things, but that is the backdrop for the next election. As the American PJ O’Rourke famously wrote, the Democrats say government “can make you richer, smarter, taller and get the chickweed out of your lawn. Republicans are the party that says government doesn’t work, and then they get elected and prove it.” The Tories will struggle to make a case for smaller government on the basis of having apparently bungled the job of running a bigger one. Rebuilding the 2019 Conservative coalition, with its diverse backgrounds and interests, will mean being honest about the choices facing the country, and imagining a state that does things better, enabling the heightened productivity – and, yes, tax cuts – that we’d all like to see.

Read this article on dailymail.co.uk