This is an edited version of the presentation I gave yesterday to the International Democrat Union Forum in London.

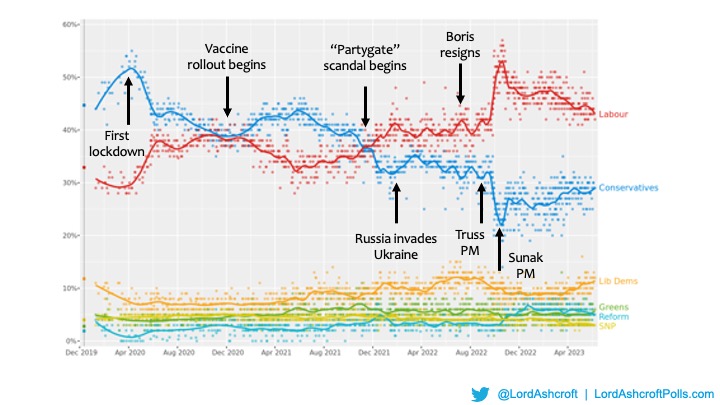

To begin with, a very brief history of British politics since the general election of 2019, at which the Conservatives under Boris Johnson won an 80-seat majority. This was their biggest victory for more than 30 years, and saw the party win seats which had never before had a Tory MP.

The Conservative poll rating continued to rise in early 2020 as Johnson “got Brexit done” and people gave the government the benefit of the doubt in the early days of the pandemic. The party’s rating came back down to earth until the gap opened once again with the beginning of the successful vaccine programme, the fastest of any major European country. The lead continued until the end of the year when the first “partygate” stories appeared.

As Russia invaded Ukraine, adding to the already spiralling cost of living, further partygate revelations, together with other stories that called the prime minister’s honesty and judgment into question, helped solidify Labour’s lead. Johnson resigned in July 2022, to be succeeded after a long leadership campaign by Liz Truss. The markets reacted badly to her bold Budget and Rishi Sunak took over six weeks later, inheriting a party with its lowest poll rating in living memory. Since then, the Conservatives’ position has progressed from catastrophic to merely very bad indeed. Let’s look at what that means in more detail, according to my latest research based on a 5,000-sample poll and focus groups around the country.

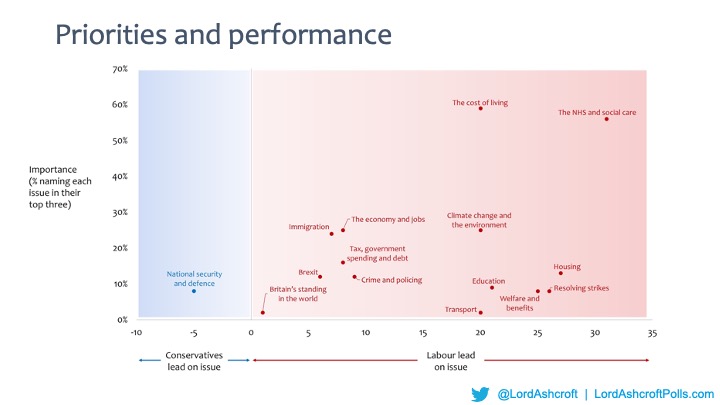

When we ask voters what they think are the most important issues facing the country, two stand out. The first is the cost of living, as I’m sure it is for many of you in your own countries. People don’t necessarily blame the government directly for price rises. But as we all know, just because something isn’t the government’s fault doesn’t mean it isn’t the government’s problem. As you may also be finding at home, people are now complaining that companies – particularly supermarkets and energy suppliers – are using covid and the Ukraine war as an excuse for raising prices and keeping them high, when they know that wholesale fuel prices, for example, have already fallen significantly. Many think governments ought to be able to do something about this, but choose not to – either because they are so out of touch that they don’t see the problem, or because they would rather protect profits than help people like them. Neither of these interpretations is very fair, but they are a natural response to real financial pressure and falling living standards.

The other top issue is the National Health Service. This is always among British voters’ biggest concerns, but has taken on a new urgency with record NHS waiting lists and strikes by doctors and nurses.

This chart also shows which party voters think would do a better job on each issue – the further into red territory, the bigger the Labour lead. As we can see, the Conservatives are ahead in only one policy area – national security and defence. The general pattern is that the more the issue matters to voters, the more likely they are to say that Labour would do a better job on it. This includes traditionally Conservative areas like the economy, crime and immigration – the third most important issue for previous Conservative voters, who wonder how the country has ended up with record net legal migration, and why we seem unable to deal with the issue of small boats arriving on our beaches from France.

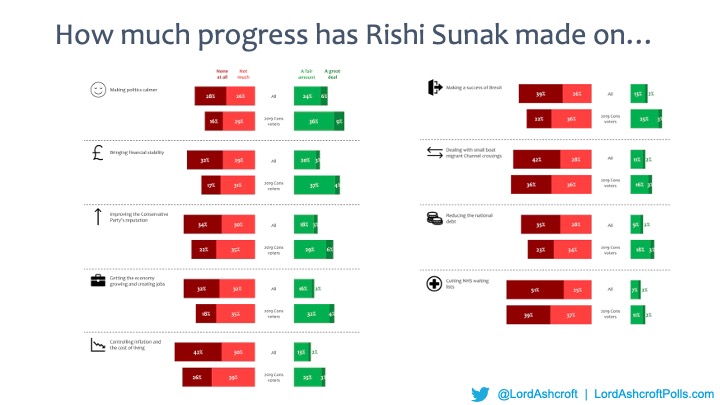

When we ask how much progress people think Rishi Sunak has made on some of these things in his first seven months in office, the picture is no more encouraging. Three in ten voters say he has managed to make politics calmer – perhaps because most of the drama now starts outside Downing Street rather than in Number 10 itself. But in all these areas, few think things are improving significantly. In the five areas the Prime Minister defines as his tests for 2023 – cutting inflation, getting the economy growing, stopping the boats, shrinking the debt and cutting NHS waiting lists – only a minority of 2019 Tories (let alone voters as a whole) think much progress has been made so far.

With perhaps just over a year until the next election, this is one reason I titled our latest research report Rishi’s Race Against Time. But apart from the challenge of trying to turn things around in the remaining months of his term, there is also a second race against time – the 13 years the Conservative Party has already been in office.

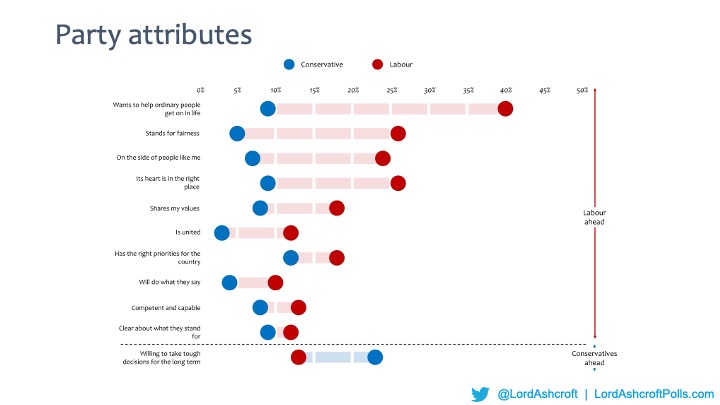

This is clear from the attributes people associate with the parties – or more to the point, don’t associate with them. Around a quarter of voters say the Conservatives are willing to take tough decisions for the long term – which can be a double-edged sword, since many voters feel they have been on the receiving end of those tough decisions. But the numbers saying the Conservatives share their values, will do what they say, or are competent – perhaps the most important quality for a centre-right party wanting to win an election – are in single figures.

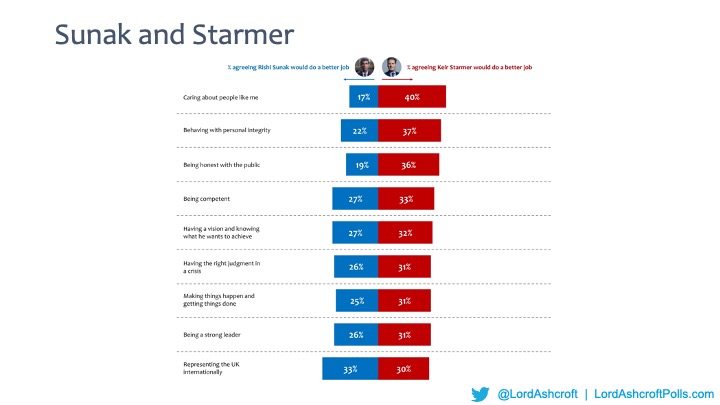

The difference is less stark when we compare the Conservative and Labour leaders directly. In areas like being a strong leader, being competent and having the right judgment in a crisis, Keir Starmer’s leads are fairly narrow, but when it comes to “caring about people like me”, the ratings reflect their respective party brands.

More worryingly, though 2019 Conservative voters choose Sunak in each case, between a quarter and a half of them say they don’t know whether he or Starmer would do a better job.

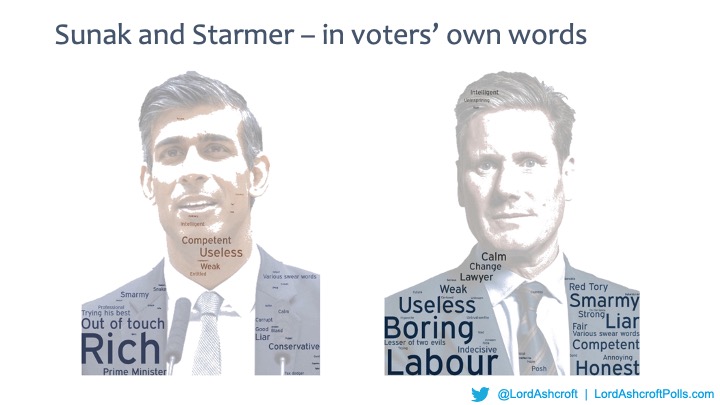

Asking people for the first word or phrase that comes to mind when they think of each leader is always revealing, though the results require careful editing before they can be presented to a civilised audience. More often than not, the first word used to describe Rishi Sunak is “rich”. While people tend to think this of politicians in general, there is a widespread view that Sunak’s wealth, and particularly that of his wife’s family, put them him in a different league. “There’s first-class rich, and then there’s private-jet rich,” as one of our focus group participants put it. This observation goes hand-in-hand with the idea that he and the government are “out of touch”.

At the same time, there were many more positive observations, especially in our focus groups of previous Conservative voters. These are usually on the theme that he is competent, professional, diligent, and working hard behind the scenes to try and solve Britain’s problems, even if there seems to be little to show for it so far. As another of our participants put it, “He’s just a normal, boring politician – in a good way. That’s just what the country needs.” They often say that while Sunak himself is trying to bring new energy to the job, the seemingly endless circus of scandal and division points to a government that is running out of steam.

Having said all that, few are so far inspired by Keir Starmer. Though many see him as competent and sensible, and certainly an improvement on his predecessor Jeremy Corbyn, many see him as “a bit of a wet fish”, to quote our focus groups once again. People note that he seems to like complaining and debating for the sake of it. Even if they think Labour are instinctively more in tune with their concerns, very few have heard of any firm policy plans to change things for the better.

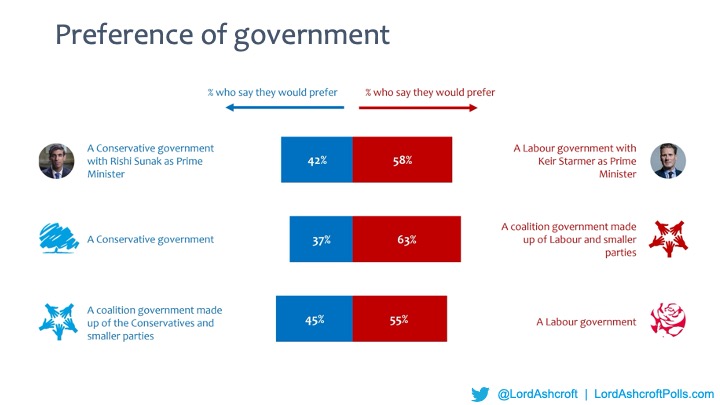

When we force people to choose between a Conservative government with Sunak as Prime Minister or a Labour government run by Keir Starmer, people chose the second alternative by 58% to 42%. The equivalent question in our final poll before the last election found voters preferring the Conservatives by the lower margin of 54% to 46%.

Even more said they would rather see a coalition between Labour and smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats, but a clear majority also preferred Labour to any kind of Conservative-led coalition.

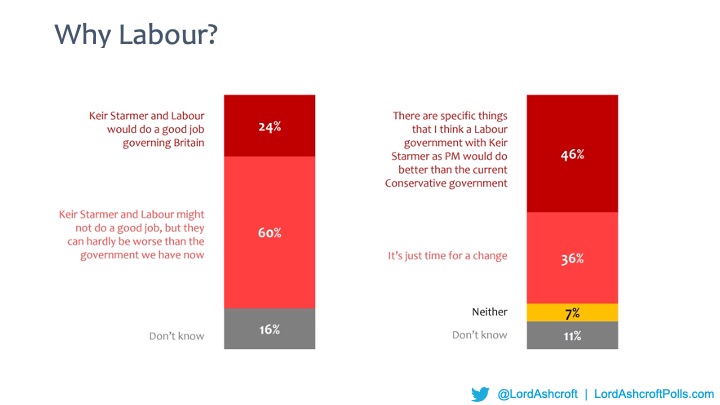

But when we ask those who prefer a Labour government why this is, fewer than a quarter say it’s because think the party would do a good job governing Britain. Most of them say Labour might not do a good job, but they can hardly be worse than the government they have now. Not exactly a ringing endorsement, though that is of little comfort to the Conservatives.

And while just under half say there are specific things Labour would do better than the current government, well over one third of them say “it’s just time for a change”.

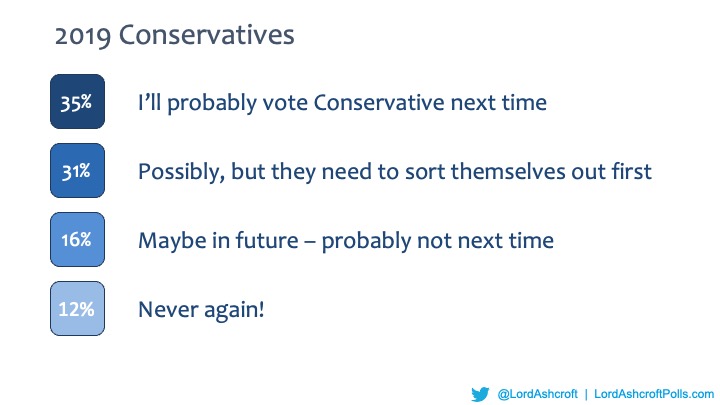

Looking at the other side of the equation, we find only just over one third of those who voted Conservative in 2019 saying they will probably do so again next time. Almost as many agree with the statement “I might vote Conservative at the next election, but they really need to sort themselves out first”.

A further 16% say they might vote Conservative again in the future, but can’t see themselves doing so at the next election. Another 12% of say they will never vote Conservative again.

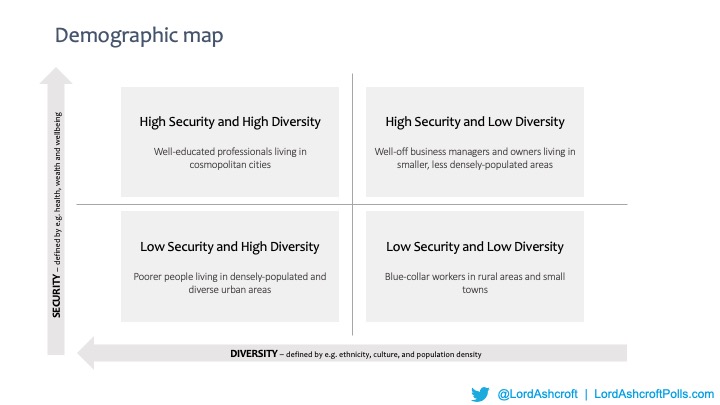

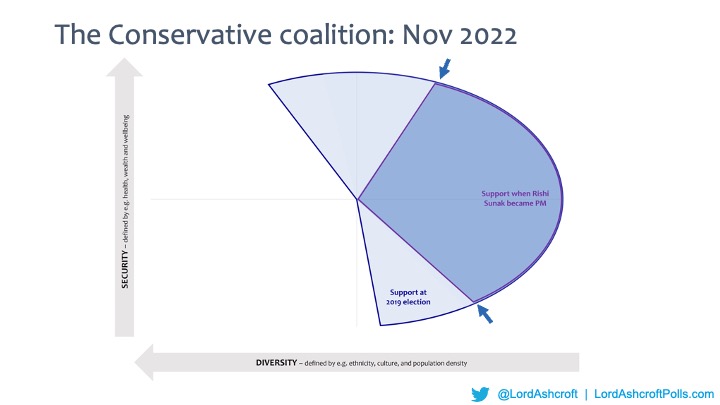

For a more nuanced picture of the evolving Conservative voting coalition we can refer to our demographic map, which I have introduced before in my work on American politics.

Our model maps the electorate according to their security on one hand the diversity of their communities on the other. The vertical axis represents Security, which includes measures like income, house value, education and health: the higher up the axis, the more secure. The horizontal axis represents Diversity, including factors like ethnicity, population density, urbanity and marital status: the further to the left on this axis, the more diverse the community. All of these are derived from census data. This means we have four quadrants of above and below average levels of Security and Diversity onto which we can map people, their views and their voting behaviour.

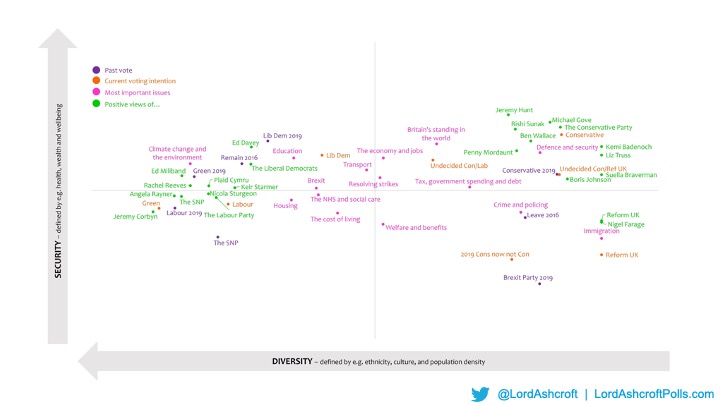

Here we see that those who voted Conservative in 2019 are most likely to be found in the high-security, low-diversity top right quadrant. Labour voters are most likely to appear in the high-diversity, low-security bottom left, and Liberal Democrats in the top left – where we are also the most likely to find Green Party voters and those who voted Remain in the EU referendum.

The low-diversity, low-security bottom right is where we are most likely to find socially conservative Leave voters, people worried about immigration – and those who voted Conservative in 2019 but say they will not do so at the next election.

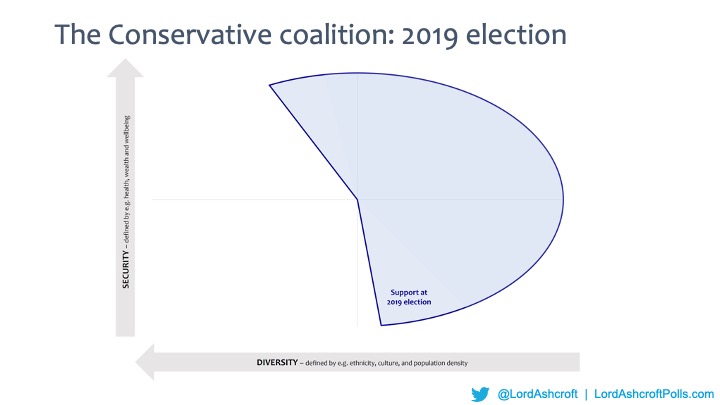

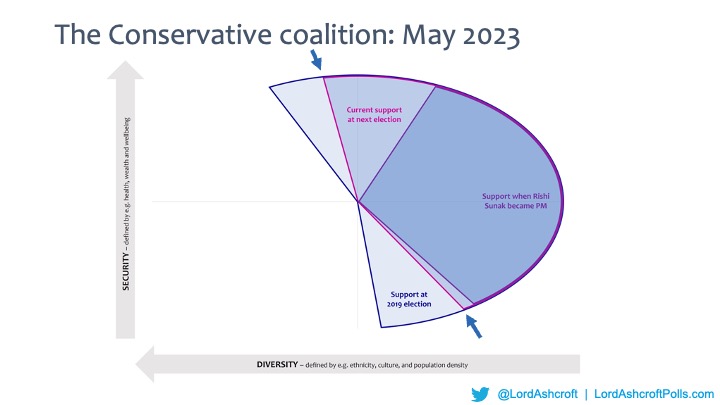

Using the same tool we can chart how Conservative support has expanded and contracted over time.

Here we see the extraordinary breadth of the Conservative voting coalition at the last election. These are the boundaries on the demographic map within which people were more likely to vote Conservative than for any other party. These were unique political circumstances: the desire to break the deadlock and “get Brexit done”, determination to keep Jeremy Corbyn out of Downing Street, and the figure of Boris Johnson, who was able almost to transcend party politics to bring together both habitual Conservatives and people who had never before considered voting for the party.

By the time Rishi Sunak took office last autumn, Conservative support had shrunk back to its core. Economic and political upheaval, together with the spectacle of a bitterly divided party after Johnson’s departure, meant the party’s poll rating had halved in two years.

Our latest round of research shows where some of this ground has been recovered – though not enough to win an election and nowhere near enough to match the 2019 triumph. What do our focus groups and data analysis tell us about these different segments?

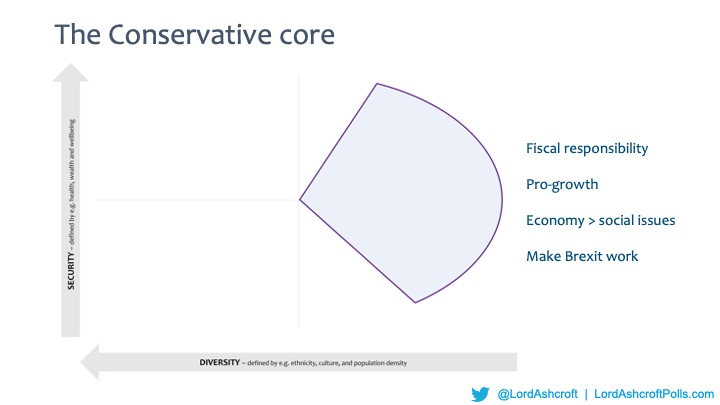

People in the Conservative core have largely stuck with the party through thick and thin. They value sound finances and supported austerity. Economic issues are more important to them than social issues and they tend to prioritise growth over environmental concerns. Most of them voted to leave the EU, and those who voted to remain would rather make Brexit work than re-open the debate.

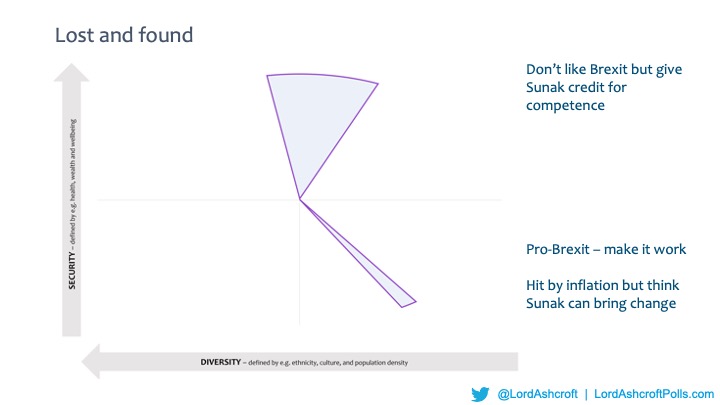

Here we see the two rather different segments of voters who have come back on board since last year’s low point. What we might call the “12 o’clock group”, prosperous and liberal, were not that keen on Brexit or austerity, but they value competence and give Sunak credit for restoring order and trying to address Britain’s problems. They think the country has terrible problems whoever is in charge, but at this stage would still prefer that to be the Conservatives.

The “4 o’clock group” largely supported Brexit and voted Conservative to get it done. Making Brexit work remains a priority which they think the Conservatives are more likely to deliver than anyone else. They are under pressure from rising prices and think change is needed, but some of them see the government trying to take action on things like small boat migration and feel that Sunak and is starting to get a grip.

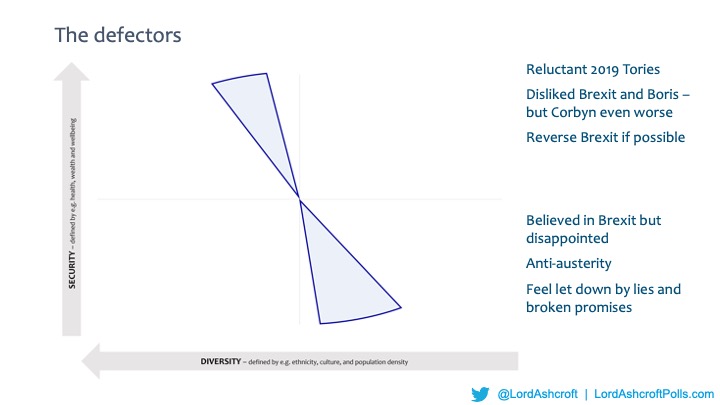

And here are the two segments who have not yet been brought back into the Conservative fold. The slice in the top left only reluctantly voted Conservative in the first place. They never much liked Boris Johnson and many of them thought Brexit was a disaster – but that having Jeremy Corbyn as prime minister would be even worse. Many of them would like to reverse Brexit if they get a chance. They value economic competence but don’t think they’ve seen very much of it under Conservative governments in recent years. They blame the Conservatives, rather than circumstances or Britain’s institutions, for the country’s problems.

Lastly, in the less diverse and less prosperous bottom right, we find many who voted Conservative for the first time because they believed in Brexit and wanted to make it happen. This is where we find many of the voters in the so-called “red wall” of former Labour seats that fell to the Tories. These voters never supported austerity, but believed leaving the EU would mean both the repatriation of powers, firmer control of immigration and more money being available for public spending in the UK. The promises to “get Brexit done” and “level up” poorer areas of the country led them to expect real improvements in their own fortunes – which, as far as they are concerned, have not appeared. These voters were also the most personally invested in Boris Johnson, often believing that he understood them as no previous politician had done, but were particularly angry about the partygate revelations. For all these reasons, they feel more disappointed and let down by the events of the last two years than any other group, and are less likely than other previous Conservative voters to feel that Rishi Sunak is in touch with their concerns.

Taken together, all of the above shows just how broad the 2019 coalition was – pro-Brexit and anti-Brexit, in favour of fiscal responsibility and big government spending, socially liberal and socially conservative – and how hard it will be to put it back together without the unique circumstances that made it possible.

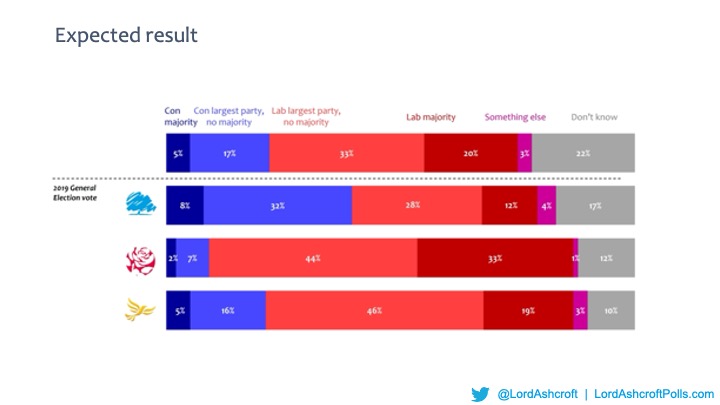

At this stage, most voters see things the same way. Only one in 20 say they expect a Conservative majority at the next election, while more than half expect Labour to be the largest party.

Can Rishi win his race against time, or is a Conservative defeat inevitable? I don’t think it is. As we have seen, Sunak has already won back large numbers of voters since he entered Number 10, and both the polls and the focus groups confirm that many more are prepared to wait longer before making up their minds. The Labour opposition has not caught the public imagination. The key will be to show that things really are improving, and that the Conservatives still have the energy, vision and discipline to govern despite being in office since 2010. The more dramas and distractions there are, the harder that case will be to make.