This article was first published in the Daily Mail.

I first visited Ukraine in 2018 to meet soldiers in the trenches of the Donbas region in the east, who were defending their country from Russian-backed separatists. I have been fortunate to return several times, and I’m in Kyiv again today to show my support on the anniversary of the invasion.

Nobody who has followed events over the last year could fail to be moved by the resilience and determination of the Ukrainian people. My latest polling only underlines that.

Most people here are prepared for the war to last months or even years longer, and I have found no appetite for any compromise with Russia or trading territory for peace.

‘Victory is the 1991 borders [the official territory declared when Ukraine proclaimed itself an independent state, free from the USSR] and joining NATO, as well as returning Crimea to Ukraine. That is a minimum,’ as one Kyiv resident said.

But even after that, the threat from Russia would remain, probably longer than Putin himself. ‘We need to become more like Israel,’ said another. ‘Since 1947 they have lived in a war situation. We need to learn from them how to live in a condition of war.’

While 85 per cent of Ukrainians say the defence of their country is progressing successfully – compared to 57 per cent of Russians who say the same of Putin’s ‘special military operation’ – they want more help.

We can be proud that they think Britain has done more than most – indeed, Boris Johnson still rivals President Zelensky himself in popularity. But while I found voters in Britain and the US most willing to offer humanitarian aid and diplomatic support to help reach a peace deal, these were some way down the priority list for Ukrainians themselves: they would most like weapons and military equipment, admission to NATO, and a no-fly zone over Ukraine patrolled by allied air forces.

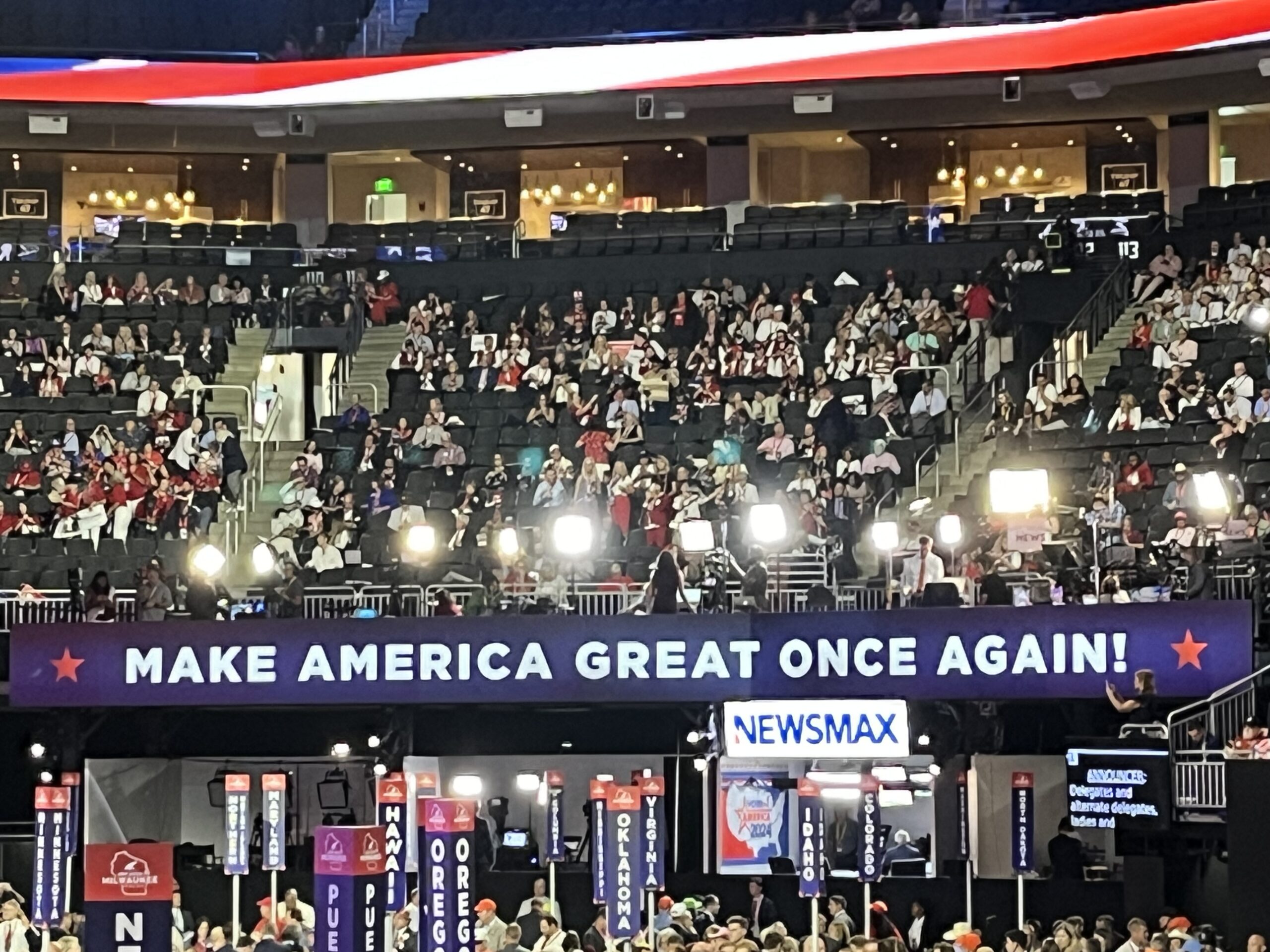

If support from allies has so far been strong, there are worrying signs of fatigue. While around half of the public in Britain and the US think their governments are providing roughly the right amount of help to Ukraine, a quarter of Americans – including four in ten of those who voted for Trump in 2020 – say they are already giving too much[itals] military support.

Only half of Republicans are happy to supply weapons and ammunition to Ukraine, compared to three quarters of Democrats. In Britain, Conservatives are keener to help militarily, while Labour voters are much more willing to accept further Ukrainian refugees.

In Britain, too, more than two thirds of the public think we have a direct interest in ensuring Russia’s defeat – or that helping Ukraine is simply the right thing to do. Only just over half of Americans agree.

Six in ten Ukrainians now believe Putin has the support of most Russians, a figure that has crept up since the invasion, and my polling suggests they are right. More than three quarters of Russians surveyed said they support the ‘operation’ – and 85 per cent have a positive view of their president.

Focus groups conducted online with people in the Russian city of Yekaterinburg exposed plenty of complaints about life – rocketing prices, shoddy goods, poor services and endemic corruption. But citizens laid the blame elsewhere.

‘It is not our president, his head is busy with more important issues,’ one Russian told us. ‘Sometimes he appoints people, and they make mistakes and he replaces them with other people. Though actually, the rate of mistakes is very high.’

Despite the absence of a quick victory, Putin has managed to control the narrative inside Russia to a remarkable degree. Around eight in ten Russians say the US or NATO are responsible for the war – that’s nearly twice as many as blame Russia itself.

Four fifths also believe NATO expansion is a threat to Russian sovereignty and that action in Ukraine was needed to protect national security.

Even so, ‘not everything is going according to the objectives,’ as one focus-group member put it. ‘On the battlefield the situation is terrible. Relatives are buying uniforms and food. People are mobilised but they send them there without taking care of them.’

Many feel their government underestimated their adversary, and six in ten Russians say Ukraine is resisting more strongly than they would have expected. Yet there is little demand for Russia to cut its losses. Many feel that whatever the reasons were for beginning this ‘operation’ in the first place, it now has to be seen through.

There is also disdain for Russians who have left the country to avoid the draft. ‘My husband ran away to Europe and I decided to divorce him,’ one woman said. ‘If he can’t defend the country, I don’t need him as a husband.’

Not everyone is so staunchly supportive of the Kremlin, though. Nearly three in ten young Russians said they opposed the invasion, and a large majority of them want to see negotiations to end the war.

But, equally, no one should run away with the idea that the Russians who are sceptical of military action are also pro-West: few have a positive view of Western countries or organisations, and a clear majority thinks the allied nations are more interested in attacking Russia than in liberating Ukraine.

Yet despite all this, Ukrainians are not just determined but also optimistic. Nearly seven in ten say they are more confident in their ability to defeat Putin than they were a year ago. ‘They expected an easy victory,’ said one Kyiv resident. ‘They didn’t consider that we are not slaves, we are civilised people. Nobody expected how the nation would unite.’