This is the text of my presentation today to the IDU Forum in Washington DC

We all know that the story of the US midterm elections was supposed to be a red wave, but we saw the Republicans take a slim majority in the House and go backwards in the Senate. My research, conducted in the weeks leading up to those elections, helps to explain what’s going on and what the implications are for the presidential election in 2024. The analysis is based on a poll of 20,000 Americans, together with focus groups in the crucial states of Pennsylvania, Georgia, Arizona and Florida.

We have used a model that helps us understand the landscape of opinion and the dynamics that drive American politics.

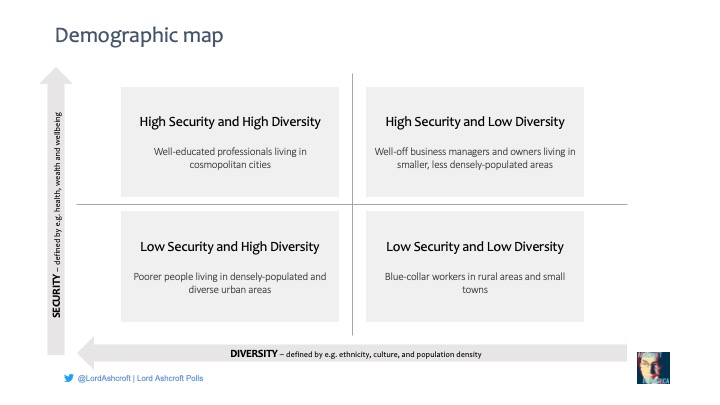

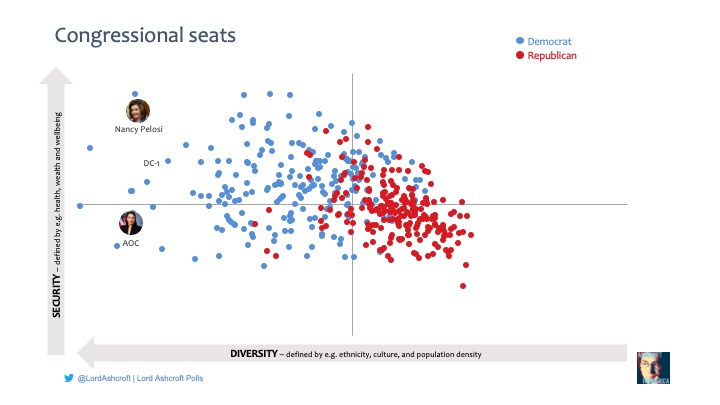

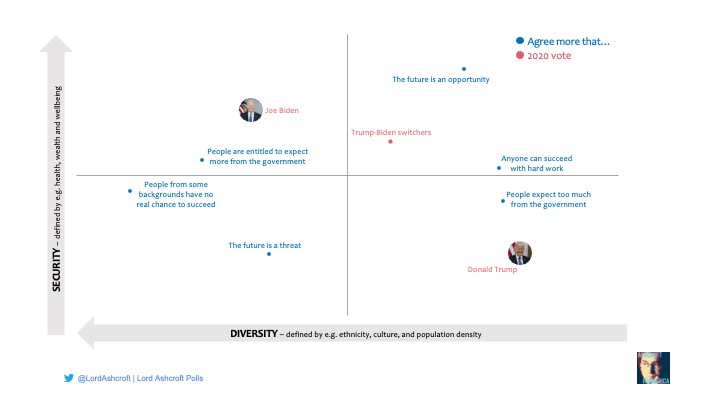

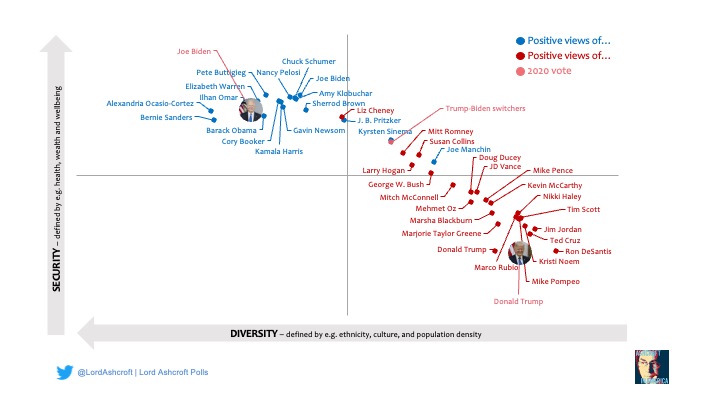

Our model maps the electorate according to their security on one hand the diversity of their communities on the other. The vertical axis represents Security, which includes measures like income, house value, education and health: the higher up the axis, the more secure. The horizontal axis represents Diversity, including factors like ethnicity, population density, urbanity and marital status: the further to the left on this axis, the more diverse the community. All of these are derived from census data. This means we have four quadrants of above and below average levels of Security and Diversity onto which we can map people, neighbourhoods, counties, Congressional districts and states.

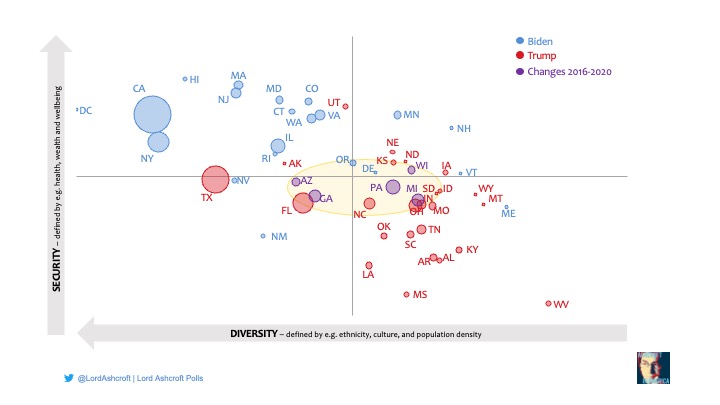

This is where the 50 states sit on that map, and how they voted in 2020. The Democrats clearly dominate the high-security, high-diversity top-left quadrant, while the Republicans do better in the lower-security, lower-diversity bottom right. It is no coincidence that the battleground states, including those that changed hands in 2020 or were home to some of last month’s fiercest Senate battles, sit close to the fault line between the two.

Overall, we see a continuation of a political and cultural divide that runs through the United States from the top right to the bottom left. But it hasn’t always been this way.

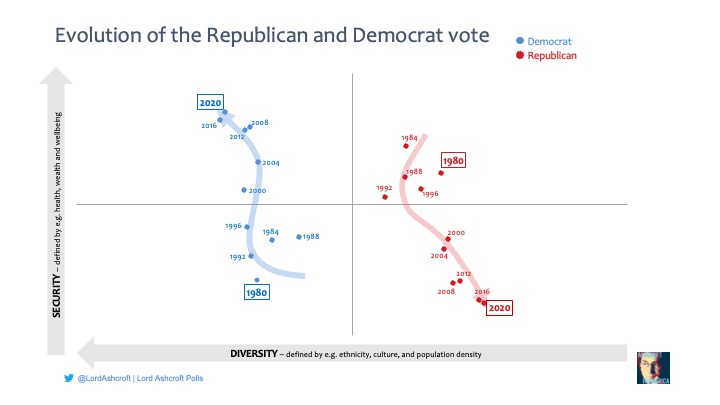

Here we see how the Republican and Democrat votes have evolved over the last 40 years – from the economic divide that dominated politics for most of the last century to the cultural divide we see today. That trend continued in 2020, with the Trump vote edging even further into the bottom right corner of the map. The Republican centre of gravity is now firmly in the bottom right – essentially, rooted in less prosperous rural and small-town America – with the Democrats representing a much more diverse and, in economic terms, increasingly upscale constituency.

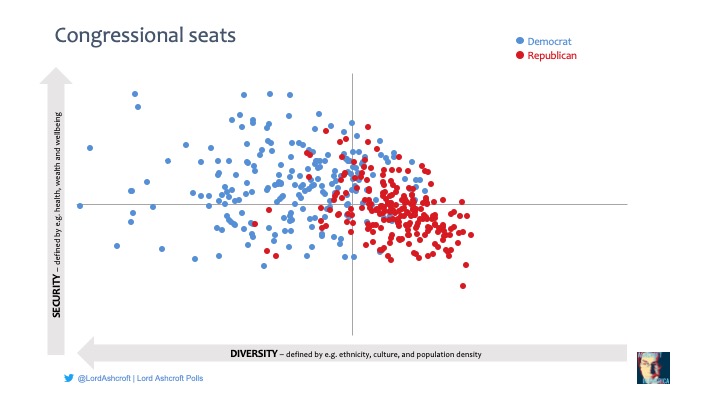

We can use the same model to map the 435 districts of the House of Representatives going into the November elections. Again, the more urban and diverse the community and the more secure its voters, the more likely the district is to be held by a Democrat. Another striking thing about this map is that liberal districts are further from the centre – less representative of the country as a whole – than conservative ones. And at the extremes of this map we get, well, the extremes.

On the far left, in both senses, we find the 12th District of California and the 14th District of New York, held respectively as you will know by Nancy Pelosi and the formidable AOC. All of which perhaps adds statistical validation to the old adage that all politics is local.

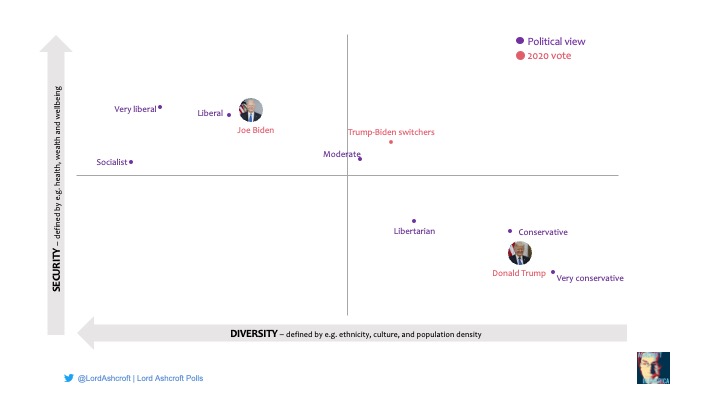

Our polling confirms what the distribution of votes and seats suggests – that conservative voters are most prevalent in the less diverse, less secure, Trump-voting bottom right, that liberals tend to be in the opposite corner, and – as I never tire of pointing out – socialists are most likely to be found among those who can afford to think that socialism sounds like a good idea.

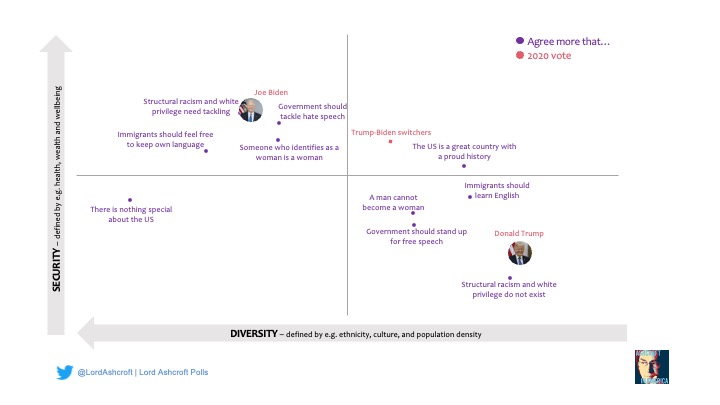

It is no surprise to see how attitudes divide on some of the current questions of culture and identity. Those who say adhere to the doctrines of structural racism and white privilege, who think the government should prioritise tackling hate speech over standing up for free speech, and who believe that anyone who identifies as a woman is a woman are naturally to be found in the liberal top-left quadrant, while those who resist those ideas are most heavily concentrated in the Trump-voting bottom right.

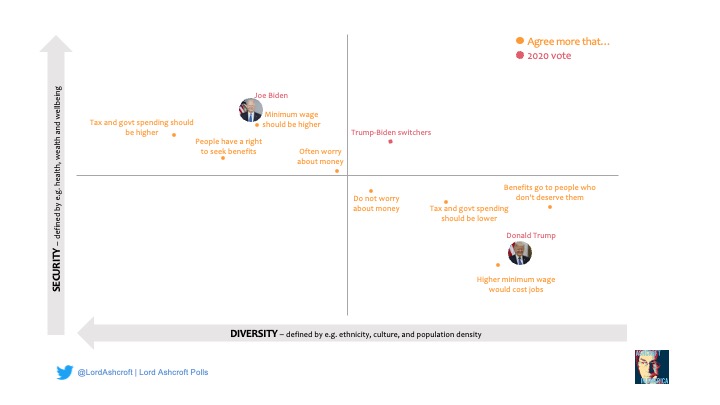

The spread of attitudes to economic issues is perhaps more surprising. It is striking that support for welfare benefits, more government spending and a higher minimum wage are most concentrated in the more prosperous top-left. Scepticism about all these things is most likely to be found among those who might be expected to benefit from them. Not only are political views in America are determined more by culture than economics, but people’s views about economic questions are themselves largely determined by their cultural outlook.

Similarly, we see that people in the less prosperous bottom-right quadrant are the most likely to think that people expect too much from the government, with their opposite numbers in liberal land feeling that government should do more. The idea that if you work hard it is possible to be very successful in America no matter what your background is still widely believed, but much more heavily concentrated in traditional Republican territory than elsewhere. The view that people from some backgrounds will never have a real chance to succeed no matter how hard they work was most prevalent among more diverse and less well-off voters, and was the majority view among those who voted for Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren in the 2020 Democratic primaries. More worryingly, it was also by a slim margin the majority view of all voters aged 18 to 24.

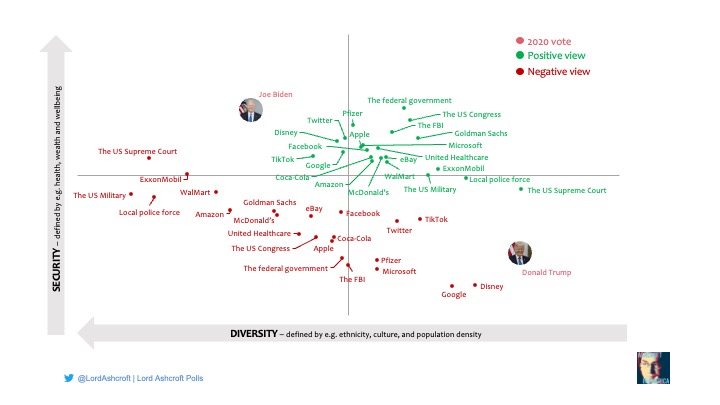

Asking people how they felt about various public and private institutions produced a slightly different but equally revealing pattern. Positive views of big businesses and government bodies was most likely to be found in the top-right quadrant – whose inhabitants have, broadly speaking, done well out of life and take a positive view of success.

Dislike of most big businesses and institutions is to be found in the most diverse, least prosperous bottom left. But it is interesting to see how Google and Disney in particular have become more politicised, with disapproval of these companies most concentrated in Trump-supporting territory. Uniquely for a government institution, and also worryingly, views of the US Supreme Court now fall along political lines.

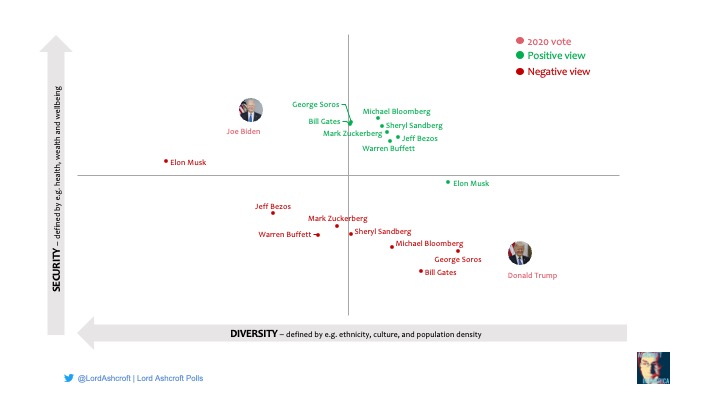

When it comes to prominent individuals in the business world, we see a similar pattern. In most cases, support is greatest in the pro-success top-right quadrant, with negative views more widely dispersed. Those with an aversion to George Soros, for example, are most likely to be found in the bottom right, as are the relatively small number who have taken against Bill Gates. Meanwhile, disapproval of the increasingly outspoken Elon Musk is heavily concentrated in the liberal quarter, while our poll shows that Republicans love Elon nearly as much as they love Ron DeSantis – of which more later.

My research did not detect great enthusiasm for the Biden administration, but this is hardly a surprise: if the voters had wanted more excitement, they would have chosen someone else. For many, Joe Biden had only one job – to prevent a second Trump term – and therefore achieved his mission before lunch on inauguration day.

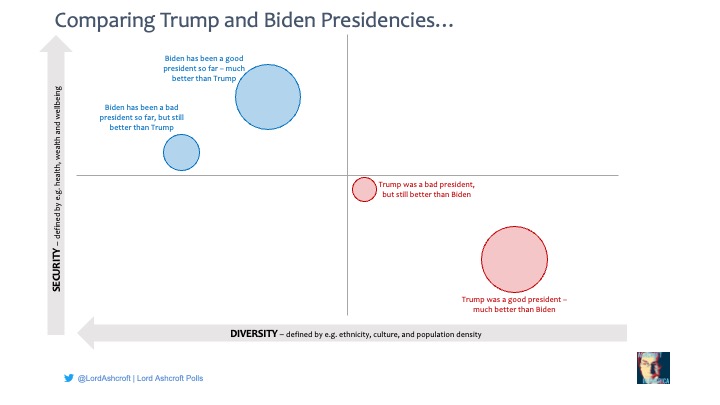

In my poll, the numbers saying Biden had been a much better president than Trump and vice versa were precisely equal, and they appear on our map where you would expect. Fully one third of Trump-Biden switchers in my poll said they now thought Trump had done a better job than his successor. But strikingly, those who think Biden has been a bad president but better than Trump are most likely to be found not in the moderate centre ground, but among much more liberal and left-leaning constituencies. If Biden is not to be the nominee next time, it is clear that there will be pressure to pick a more radical candidate.

In our focus groups there was a degree of relief that the tweet-fuelled daily circus had come to an end, but few thought Biden had quelled the country’s underlying political tensions. In fact, by calling MAGA Republicans semi-fascists and a threat to democracy, many felt he was doing quite the opposite.

In policy terms, apart from mentions of student loan forgiveness and some environmental initiatives, many felt there had been little to show for 18 months in which the Democrats controlled the White House and both Houses of Congress.

Underlying all this was the question of whether Biden was up to the job. In our groups, voters of all shades of opinion felt the president seemed to be experiencing what they delicately described as “age-related issues” and often appeared confused in his public appearances. This made them wonder who was really pulling the strings – staff, Congressional leaders, or other forces within or outside the Democratic party. The general expectation was that he would not run in 2024, and even if he did, excitement about such a prospect was hard to detect.

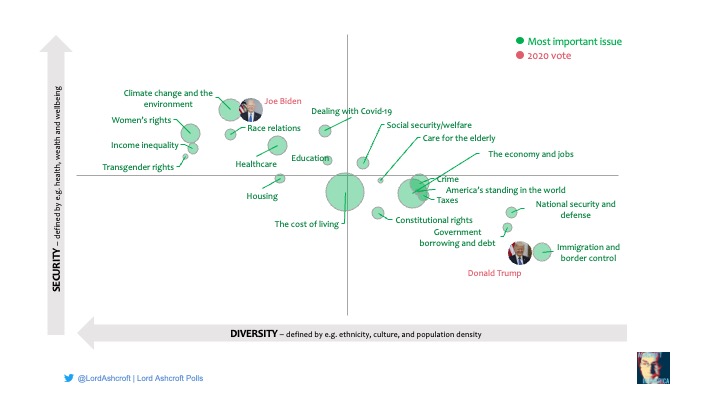

Our polling on the most important issues facing the country – and how those concerns are distributed among the different parts of the electorate – tells us a lot about the outcome in November. You might say that we were looking at one midterm, but two elections.

The fact that the cost of living appears as a big blob in the centre shows this was not only the voters’ biggest policy concern, it was shared across the electorate. Certainly, it was the first issue to be raised in all our focus groups. Aside from this, we can see how two sets of voters had very different things on their agendas.

People in the top left, most liberal quarter of the population are not necessarily the only ones to care about climate change, race relations or transgender rights. However, it is the case that these voters are more likely to put those things at the top of their priority lists.

Meanwhile, national security and especially immigration and border control are bigger concerns among low-security voters of the conservative bottom right than they are in prosperous liberal territory.

This division over values and priorities helps explain the results we saw in the midterms.

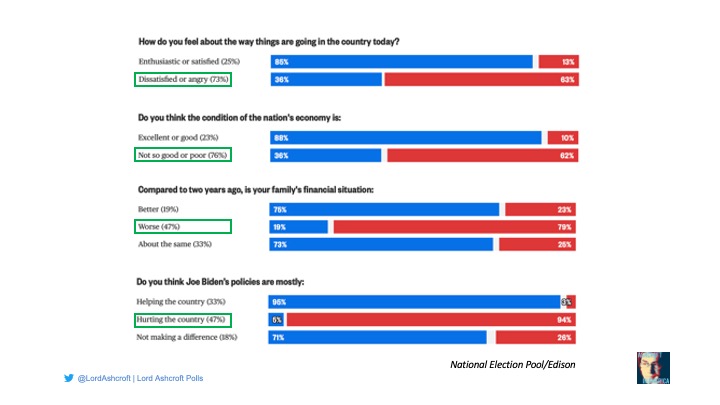

A look at the exit polls show just how remarkable those results were given the immediate circumstances. Three quarters of those turning out to vote said they were dissatisfied or angry with the way things were going and that the economy was in bad shape. They were more than twice as likely to say their financial situation had got worse in the last two years as to say it had improved. And they were much more likely to say President Biden’s policies were hurting as to say they were helping.

Even in a polarised country, answers like that would normally point to the red wave that many expected. So why didn’t it materialise? Two further questions offer clue.

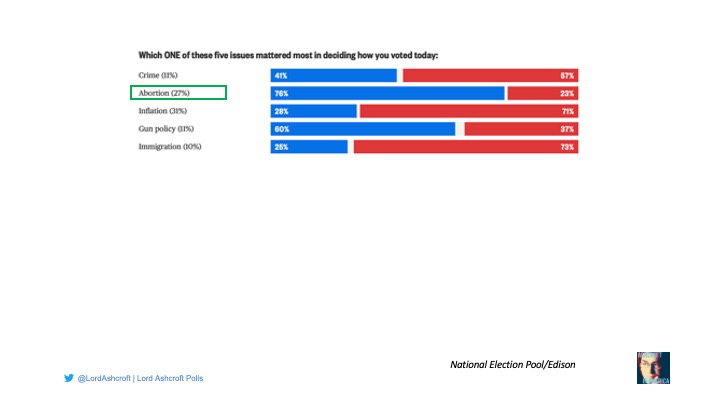

One is the issues that people had in mind when casting their vote. As we saw on our map, the question of women’s rights is more likely to top the agenda for top-left liberals than for other people. But the overturning of Roe v. Wade has given it a new significance across the board. The issue galvanised Democrats and pushed moderate voters – not just women – towards pro-choice candidates.

My focus groups found that opinion on this issue, especially among potential Republicans, is more nuanced than you might infer from the news coverage. My poll found a majority overall, including nearly 4 in 10 Republicans, saying that laws on the issue should be made at a federal level and apply across all states. Many agree with the Supreme Court ruling that abortion rights are not guaranteed by the constitution, but at the same time worry about what they see as extreme restrictions proposed by some red states, and the idea that the law on an issue like this should vary so widely between different parts of the country. At the same time, uncommitted voters told us they would look more carefully at candidates’ views on the question – a major reason why more than half of self-described moderates backed Democrats in November, and why the result defied the usual laws of political gravity.

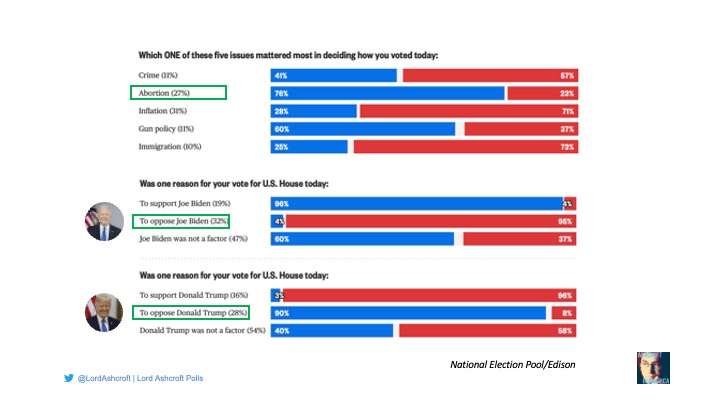

The other reason relates to two people who weren’t even on the ballot. Midterms are traditionally seen as a referendum on the incumbent president. But this year, remarkably, almost as many people said they used their vote in the House election to oppose Donald Trump as to oppose President Biden.

It was clear from our focus groups that Trump was not necessarily going to be an asset in these elections. While he certainly retains committed supporters, some had grown weary of his antics. If they thought the reaction to the events of January 6 was overblown – “it was like a bad tailgate party that got out of hand”, as one put it – they also thought he ought to have done more to calm things down and uphold the dignity of the office. Or, to quote another Trump voter from Arizona, “dude, you were Commander-in-Chief”.

We heard in Georgia, Pennsylvania and Arizona that potential Republican voters had severe doubts about the merits of the Trump-endorsed candidates on offer – especially if they loudly denied the result of the last presidential election – and the fact that Trump had endorsed them was at best a mixed blessing. Across the board, Trump-endorsed candidates did less well than other Republicans, with Herschel Walker in Georgia, Dr Oz in Pennsylvania and Kari Lake in Arizona some of the most obvious examples.

But what of the other figures on the scene?

Asking how people feel about different politicians reveals an interesting pattern of support. For example, we see that those who currently have the most positive views of Joe Biden are further to the right on our map than the centre of gravity of those who voted for him – suggesting that many more liberal voters held their nose to elect him, or have since lost confidence in his presidency, or a combination of the two.

We can also see the respective positions of Liz Cheney and Joe Manchin. By taking a principled stand against the leadership in their own party, each has won the respect of moderate voters but in the process won more admirers among opponents than on their own side. Meanwhile George W. Bush, once criticised as one of the most divisive presidents in history, has become almost a centrist figure.

Those with the most positive views of Ron DeSantis, you will notice, are firmly in Trump territory, which clearly has intriguing implications for the run-up to 2024. We found in our focus groups that Republicans outside Florida respected the way he stood up for his state, and had looked with envy at his light-touch covid regime. His own voters particularly enjoyed his outspoken defence of conservative values and his approach to education and parental choice. Interestingly, liberals often told us they worried about him more than Trump: “he’s scarier because he’s smarter” was the usual verdict. DeSantis’s 19-point victory, including comfortable wins among working-class voters and in majority-Hispanic counties, show how it’s possible to deliver an economically and culturally conservative message in a less divisive way.

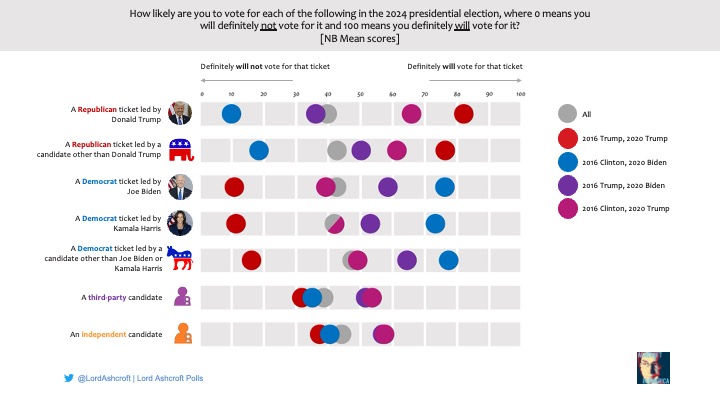

In my poll before the midterms I asked how likely people currently thought they were to vote for various presidential tickets, on a scale from zero to 100. However lukewarm their response to Biden, I found Democrats even less keen to turn out for a ticket led by Kamala Harris – indeed, at this stage, it looks as though the Democrats would do best with a ticket led by neither of them.

On the red side, voters as a whole said they were more likely to vote for a non-Trump Republican than for Trump himself. This was especially true of 2020 Biden voters, and even more so of those who switched from Trump to Biden two years ago.

In this context, the result we saw in November was arguably the best possible outcome for the Republican party, for three reasons. First, the slim House majority is enough to rein in the Democrats’ ability to legislate. Second, it will tempt the Democrats to believe that their agenda is much more popular than it really is. And third, it forces the Republicans to ask why they didn’t do better and what is needed to win back the White House.

In doing so, they need to ask what they want the presidential election to be about. If it is all about the record of the current administration, and competing plans for the future, the Democrats should be on shaky ground – especially if Biden decides to run again. After 2020 and 2022, do the Republicans really want another referendum on Donald Trump?

As we know, Trump expanded and mobilised the Republican base, and attracted more minority voters to show that demography is not necessarily destiny. But given the results we saw last month, is he still best placed to take back states like Georgia, Pennsylvania and Arizona, and carve out a path to 270 electoral votes?

Given the recent evidence, I think the answers to those questions are pretty clear. But turning the page on Trump, if that’s what the party decides to do, cannot mean turning the page on his voters. He was a symptom and an accelerant of the tensions we see today, not their cause. He won by giving a voice to the voters and their concerns. The job of his successor will be to pull off the same trick.