Joe Biden’s inauguration today will be greeted with a huge sigh of relief by millions in America and around the world. The moment crowns the victory not just of Biden, but of the institutions of American democracy that many still fear are under threat. After a fortnight of extraordinary drama that saw the storming of the Capitol building and a second impeachment for an outgoing President, it would be easy to lose sight of the bigger picture – the movements that brought American politics to where it is, and their effect in the election that feels as though it took place not just eleven short weeks ago but in another age.

If the 2016 election that sent Trump to the White House will stand as one of the defining political events of our time, its successor last year was in many ways at least as remarkable: the supposedly unpopular President winning more votes than any previous Republican, losing only to the candidate with the most votes ever. This week I am publishing my analysis, based on four years of research throughout the US as well extensive polling and focus groups during the 2020 campaign. The research both helps to explain what happened and why, and gives some clues about what we can expect in the next chapter of American politics. Here are some of the key points.

What is President Biden’s mandate?

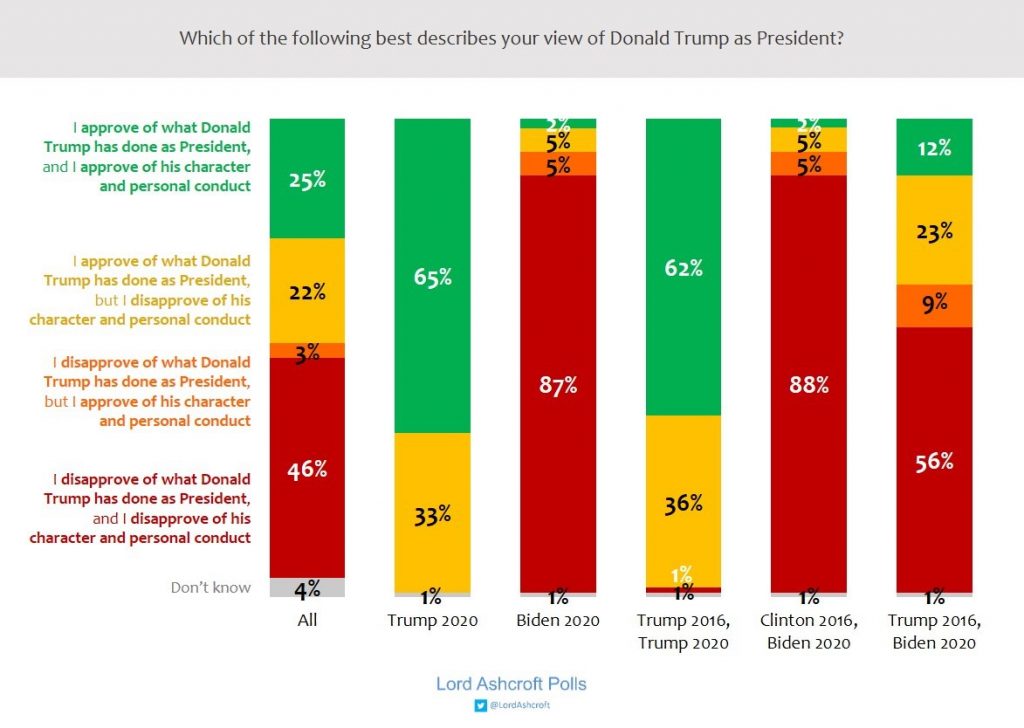

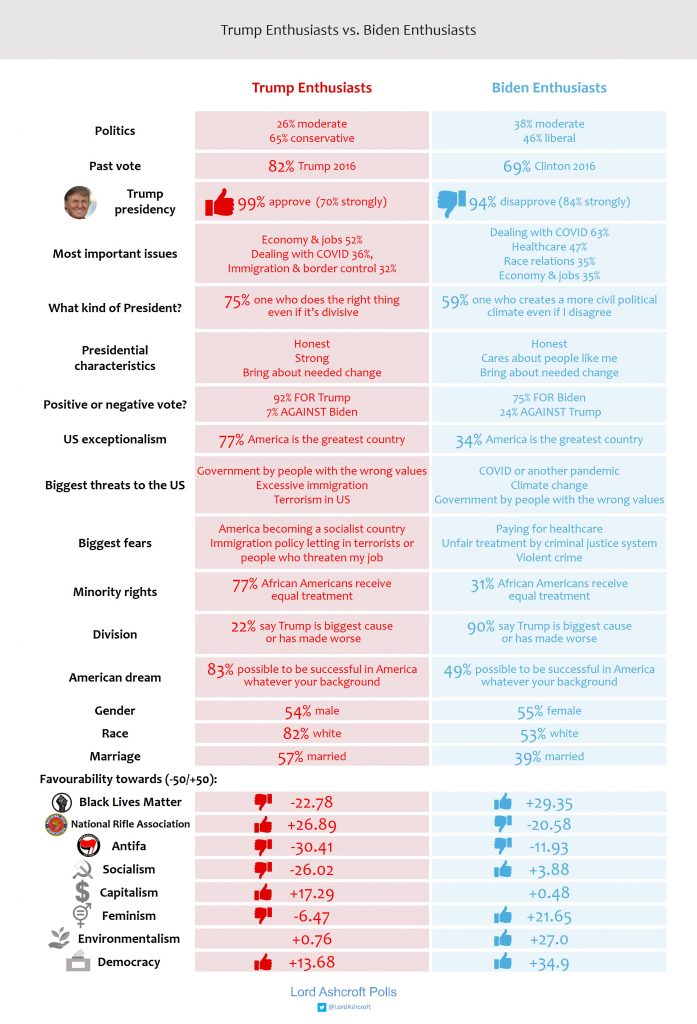

With a record-breaking haul of 81 million votes, Joe Biden is the most successful presidential candidate in American history. But for many voters, the election was not about Biden but a referendum on Donald Trump. I found 99% of Trump supporters saying they approved of the job he had done, and 9 in 10 said they would be voting for the incumbent; 94% of Biden supporters disapproved of Trump’s performance and a quarter said they were voting mainly to get rid of him.

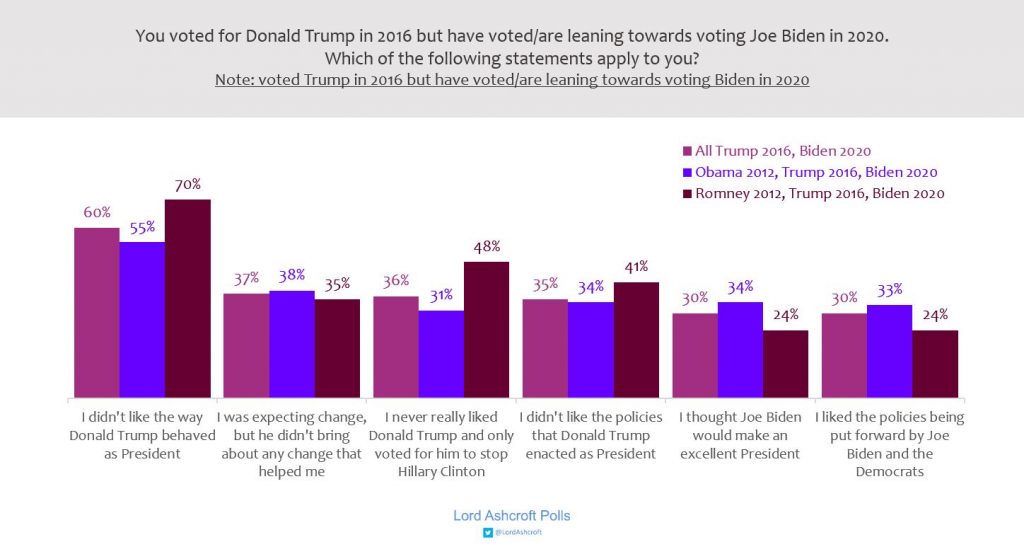

Those switching from Trump to Biden were most likely to mention disillusionment with Trump among their reasons; having high expectations of Biden or liking Democrat policies were at the very bottom of the list.

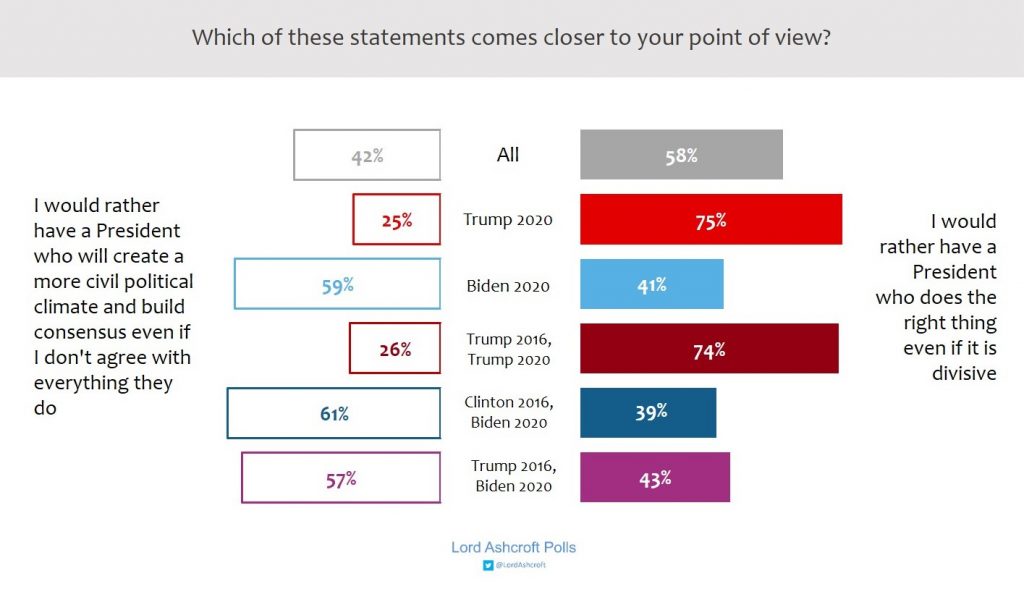

While policy concerns were different for Trumpers (the economy, immigration) and Biden backers (covid, healthcare), another telling difference was the kind of leader they wanted. While three quarters of Trump enthusiasts would rather have a President “who does the right thing even if it is divisive,” a majority of Biden supporters would prefer one “who will create a more civil political climate and build consensus even if I don’t agree with everything they do.”

In other words, for many voters Biden had one job – to see off Donald Trump – and he will accomplish his task today. The new President’s problems will begin with whatever he decides to do next. As with any successful political movement, especially one of this size, the coalition that elected Joe Biden in 2020 is far from being a monolithic bloc. Its foundation is the Democratic base, many of whose members yearned for a more liberal, progressive direction and found the compromise of nominating an established moderate quite agonizing. Many of them hoped that Biden’s victory would, in fact, usher in a much more radical Democratic era than might have been suggested by the new President’s record in Washington or his reassuringly temperate campaign style. These were joined by a group of new voters, younger and more ethnically diverse, who were opposed to Trump and all his works and were particularly driven by to address racial injustice.

Then there is a much more moderate set of voters who wish above all for a calmer, less acrimonious form of politics. Less inclined to dismiss the Trump years out of hand, they were more likely than most to prefer a President who creates a more civil political climate. If they had doubts about Biden it was over his age and health, and the prospect that he might quickly be succeeded by a new face with a more radical agenda. What they wanted was not a Green New Deal but a bit of peace and quiet. Yet with Vice President Harris having the casting vote in a 50-50 Senate, the Biden administration has little excuse not to be bold. The potential for conflict and disappointment among his supporters is already apparent.

Trumpism without Trump?

Some see the 2020 election as a repudiation of Donald Trump and it’s presidency. Arguably, it’s a funny sort of repudiation that sees a President win 11 million more votes, and a higher vote share, than he did four years earlier. For many, the temptation to dismiss Trump supporters as the “basket of deplorables” and lump them all in with the Capitol-storming extremists will be greater than ever. But this would be an injustice and a mistake. As his reputation implodes, it is as important as ever to grasp what it was about the Trump offering that nearly half the electorate found so compelling.

Looking back at what he did and what his supporters told us during four years of research, I think this can be distilled into what we might call the Seven Tenets of Trumpism. An enduring belief in American exceptionalism – the idea that the US is different from, and in important ways, greater than, other countries; conviction that constitutional freedoms like free speech and the right to own guns are important and need defending; the belief that it is possible for anyone who works hard to be successful in America, whatever their background; rejection of political correctness and identity politics; belief in business, low taxes and deregulation; support for a forceful, independent foreign policy; and – crucially – willingness to tolerate a good deal of friction in politics in the cause of advancing these things.

The question for the Republican Party is whether this powerful proposition can be disentangled from the 45th President himself. Could you have Trumpism without Trump? In my research, one in three Trump supporters told us they approved of what he had done as President but disapproved of his character and personal conduct. This meant two thirds of his supporters said they approved of both his actions and the way he behaved. That’s not to say most will not have been horrified as they saw the seat of their democracy under attack. But for most of his presidency, what others saw as his outrageous behaviour was not just part of the package, but part of the appeal – a feature, not a bug. Many loved having a President who said exactly what they thought, refused to conform to politically correct orthodoxies and remained a political outsider.

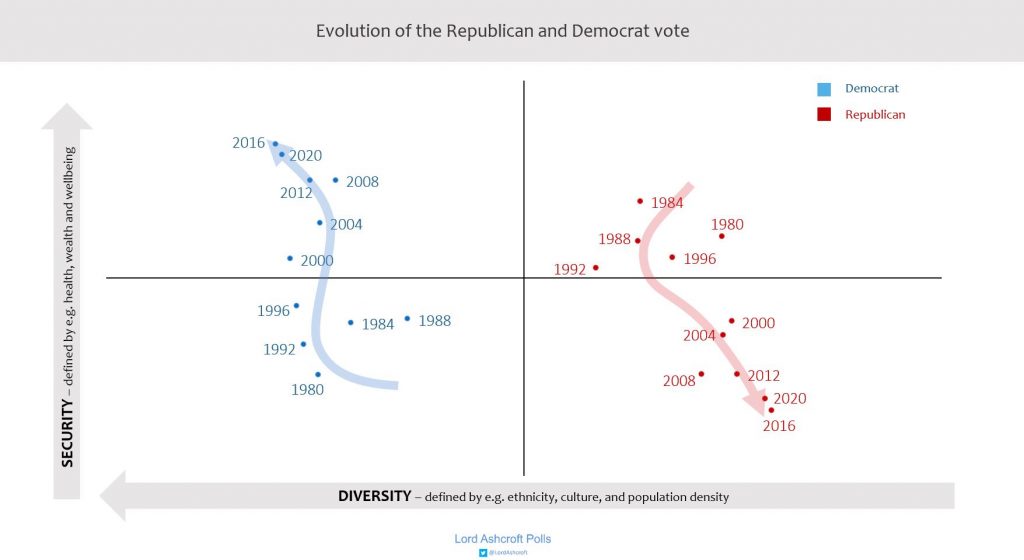

Some would like the Republicans to put the whole Trump era behind it, but it won’t be that simple. The two parties in American politics have always drawn the base of their support from very different constituencies, but over the last forty years that fault-line has shifted completely.

On this map, the vertical axis represents security, in terms of things like health, income and occupation – the higher up, the more secure. The horizontal axis represents diversity, which includes factors like ethnicity and population density – the further to the left, the more diverse. Over the last 40 years, the Democratic party’s base of support has in economic terms grown steadily more upscale, while the Republicans have become the party of rural and small-town America. The coalition that sent Trump to the White House is different from the one that elected George W. Bush, let alone his father. In charting its new course, the Republican Party cannot simply trade this coalition in for a new one.

The task the Republicans now have is to hold together that base of support, and even expand back into the suburbs and cities themselves. To say that President Trump’s performance since the election has made this task harder would be an understatement of colossal proportions. Those who want it to remain “Donald Trump’s Republican Party” (as Don Junior had it at the fateful rally) might try the patience of mainstream Republicans beyond endurance: being uncouth on Twitter is one thing, inciting insurrection is altogether another. But those who want a Trump-free future for the GOP must find a way of distancing themselves from him while holding onto the millions – minus the extremist minority – that he brought into the Republican fold. This leads to another question – for another day – of whether the GOP will even continue to exist in its current form.

Can Biden reunite America?

For four years, Donald Trump has been the focal point for divisions in American politics. But if he exacerbated those divisions, he did not create them. As we can see from this dashboard of our polling during the campaign, there are deep and genuine differences in outlook, priorities and values: the issues they care about, whether they believe minorities enjoy equal rights and opportunities, the role of the government, how the Constitution should be interpreted, and the things they worry about on a daily basis.

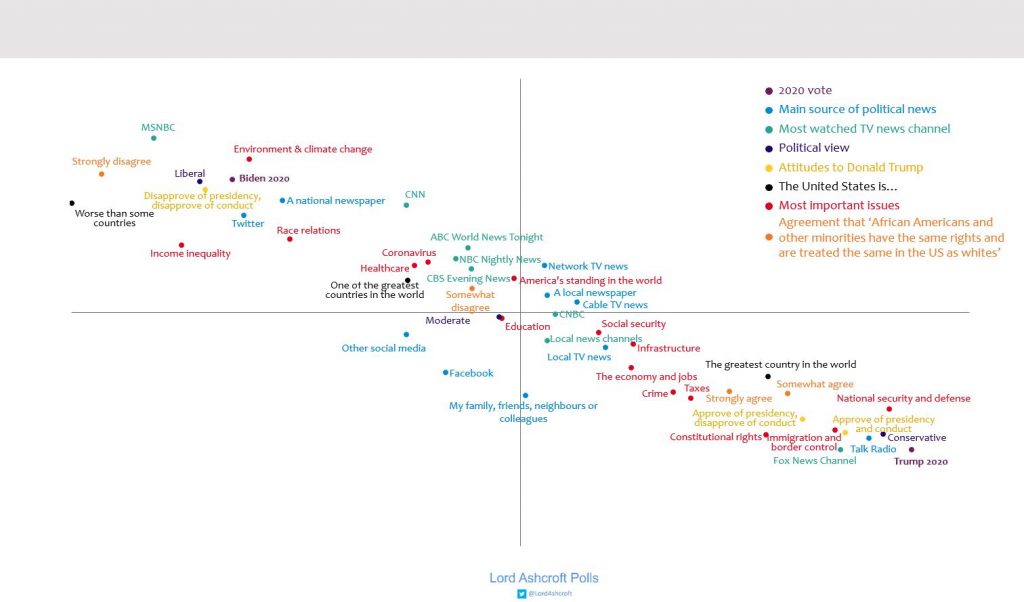

Combining these various views and attributes on one map makes for an interesting picture of the electorate. We see here how different issues, attributes, personalities and opinions interact with one another. The closer the plot points are to each other the more closely related they are.

We can see how issue concerns, political outlook, news sources, views of American life and Donald Trump’s presidency were associated with support with one or another candidate at the 2020 election.

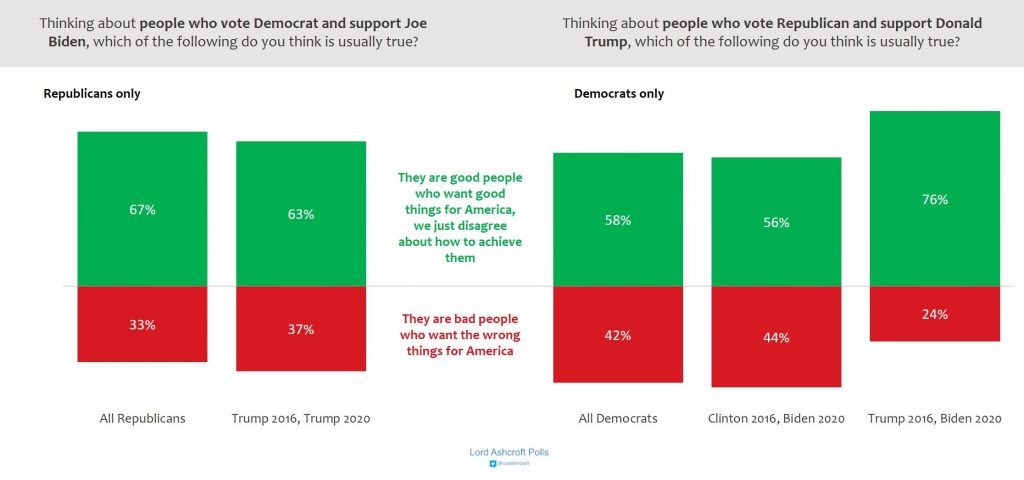

Such a divergence of views and priorities is the stuff of politics, and an equivalent map could be drawn of the electorate in any democracy. The divisions are made more acute, however, by the way each side views the motivations of the other.

Two thirds of Republicans said they thought people who vote Democrat and support Joe Biden were “good people who want good things for America, we just disagree about how to achieve them.” However, only just over half of Democrats were prepared to say the same about Republicans and Trump voters: 42% said these were “bad people who want the wrong things for America,” including majorities of those who voted for Bernie Sanders in the 2020 primaries and those who describe themselves as very liberal, and two thirds of self-declared socialists.

Nine out of ten Biden enthusiasts said either that they thought Donald Trump was the biggest cause of recent divisions in society or that he had made existing divisions worse. Most Trump supporters, meanwhile, thought America would be just as divided even if he had never run for President.

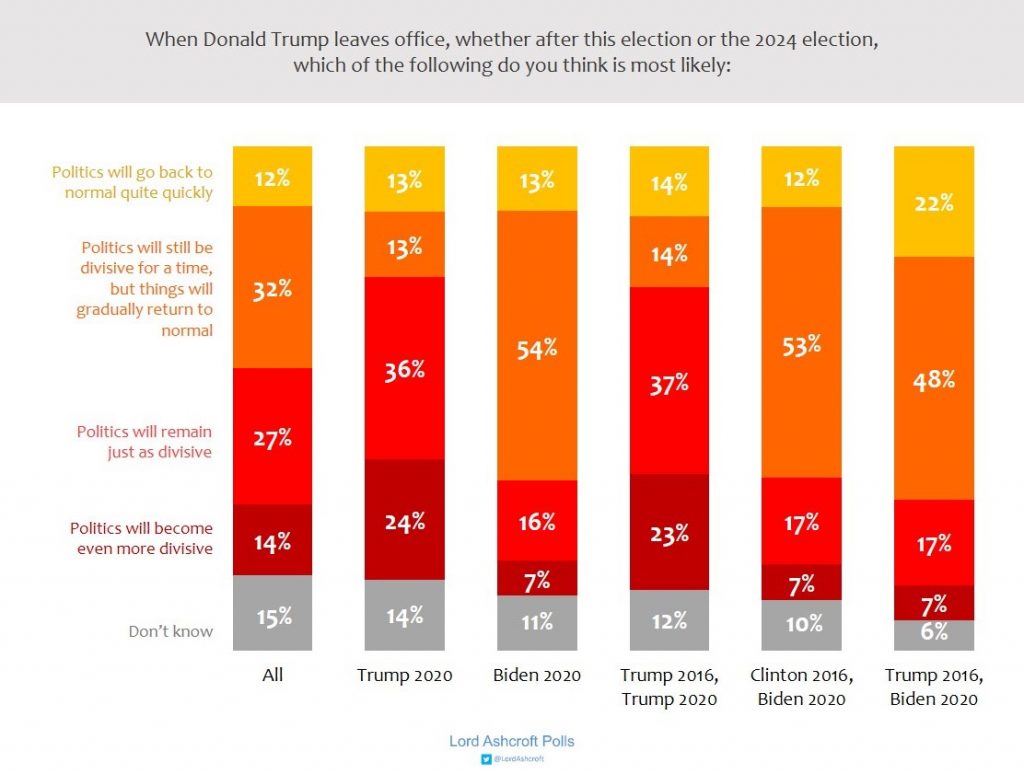

Accordingly, the two camps took different views when asked about politics in the post-Trump era. Only a small minority of voters thought things would go back to normal quite quickly when Trump left office. But while a majority of Biden enthusiasts and almost half of Biden-Trump switchers thought things would gradually return to normal, six in ten Trump enthusiasts thought politics would either remain just as divisive or become even more so after Trump’s departure.

While Biden supporters often said they wanted more unity and less division, this often seemed less evident in the way they spoke about the people who voted for Trump. “There’s a lot of effing stupid people in our country,” said one Democrat reflecting on the 2016 result. “Idiots and frickin’ old, racist white men.” The idea that his voters had simply lacked guidance by better informed people such as themselves was also a regular theme: “Did we not do enough to reach out? Did we not do enough educating the people in our lives?” agonised one woman. “Some of my friends have Trump signs all over their yard and I still love them, and our children still play together. But that doesn’t mean I don’t think they have received stupid misinformation.”

Trump voters, meanwhile, felt strongly that the calls for agreement and consensus were only really aimed in one direction. “I’m a middle-aged white conservative Christian male. All of this inclusiveness and unity, and what they’re really saying is that nobody else has to change their mindset but me.” The supposedly tolerant left “is only tolerant if you agree with their opinion. If you voted for Trump, then you’re the enemy.” As for the idea of Biden ending the divisions, “It’s like they’re going to wave a magic wand and fix everything that’s wrong now. If Jesus came back and was the President, I’m not sure he himself could do it.”

Reunited Nation? American Politics Beyond The 2020 Election is published this week by Biteback.