The covid crisis has dominated the news for so long that it sometimes seems as though politics has gone into suspended animation. But as the agenda moves on, the challenge for parties in consolidating and expanding their coalitions of support remains the same. As I argued in yesterday’s Mail on Sunday, Boris Johnson and Keir Starmer each have a conundrum to wrestle with on that front. My latest research, published today, looks in detail at how voters have reacted to the government’s handling of the crisis, what they make of Labour’s new management, and how much – or how little – the pandemic has transformed the political landscape. The full report is below, but here are the main points.

Overall, I found people more likely to think the government had underreacted to the pandemic than overreacted. Half of 2019 Conservative voters thought this – including two thirds of those who had switched from Labour – as well as more than six in ten voters overall. Many thought the big mistake had been to act too slowly at the beginning, especially continuing to allow flights from China and other badly hit countries.

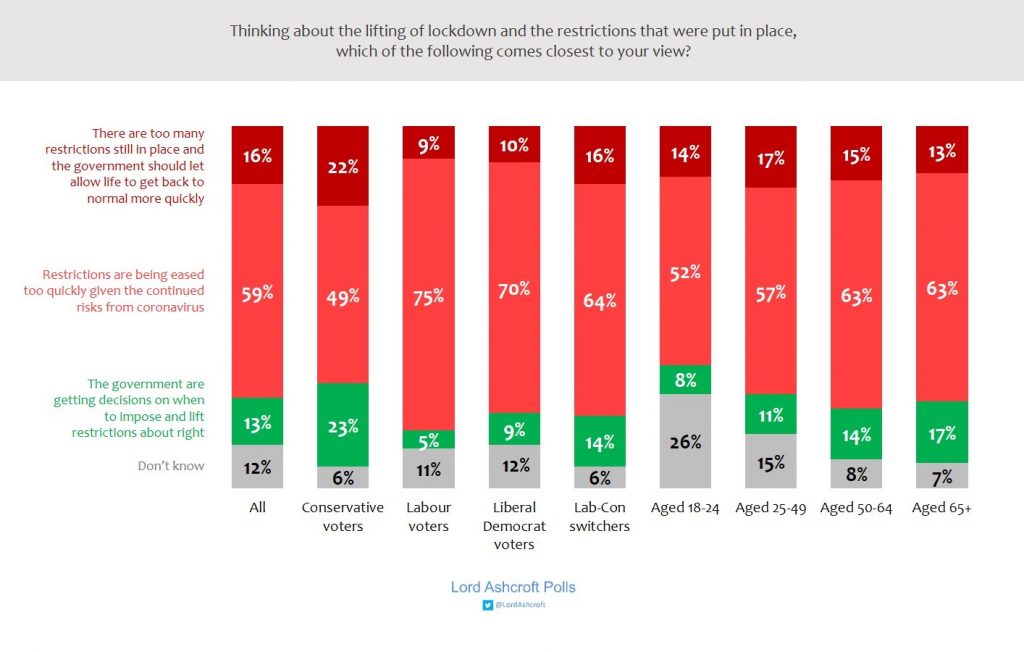

For all the complaints from Conservative MPs about continued constraints and the imposition of new rules, many more think restrictions have been lifted too slowly since lockdown than that there are too many still in place. More than half of all voters, again including half of 2019 Tories, thought the rules had been eased too quickly. It was notable that self-employed people were more likely than most to say there were too many restrictions still in place and the government should allow things to get back to normal more quickly.

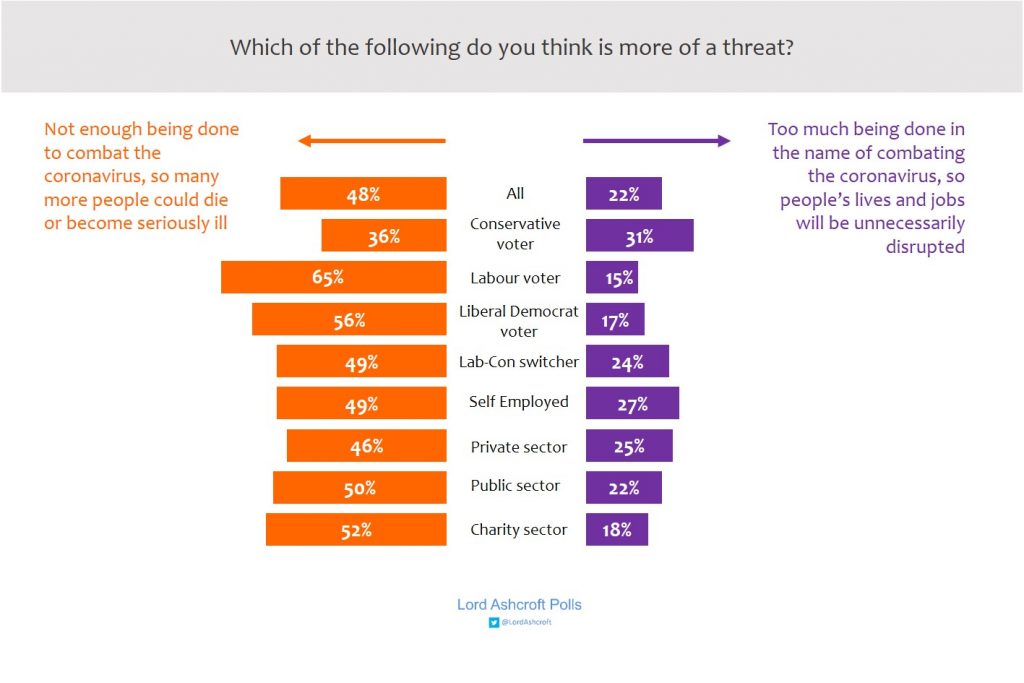

By the same token, when we asked which people thought was more of a threat – not enough being done to combat the coronavirus so many more could die or become seriously ill, or too much being done in the name of combating the virus so people’s lives and jobs were disrupted unnecessarily – people chose the former by a wide margin. Conservatives were the most closely divided, however, and again self-employed people were more likely than most to see unnecessary disruption as the greater threat.

In our focus groups, people tended to blame the rise in cases on people not following the rules, rather than the rules themselves – but often put this down to complacency or confusion over apparently mixed messages from the government. “One minute it’s ‘go back to work,’ then it’s ‘work from home’. It’s frustrating, so I think people will just do what they want to do,” as one put it. While voters gave the government fair marks for “protecting people’s jobs and incomes” and “making sure the NHS has been able to cope with the number of coronavirus patients” (the furlough scheme and Nightingale hospital programme were often praised spontaneously in focus groups as real achievements), the lowest scores were given for “making the right decisions at the right time” over when to impose and lift restrictions, and “communicating the rules clearly.”

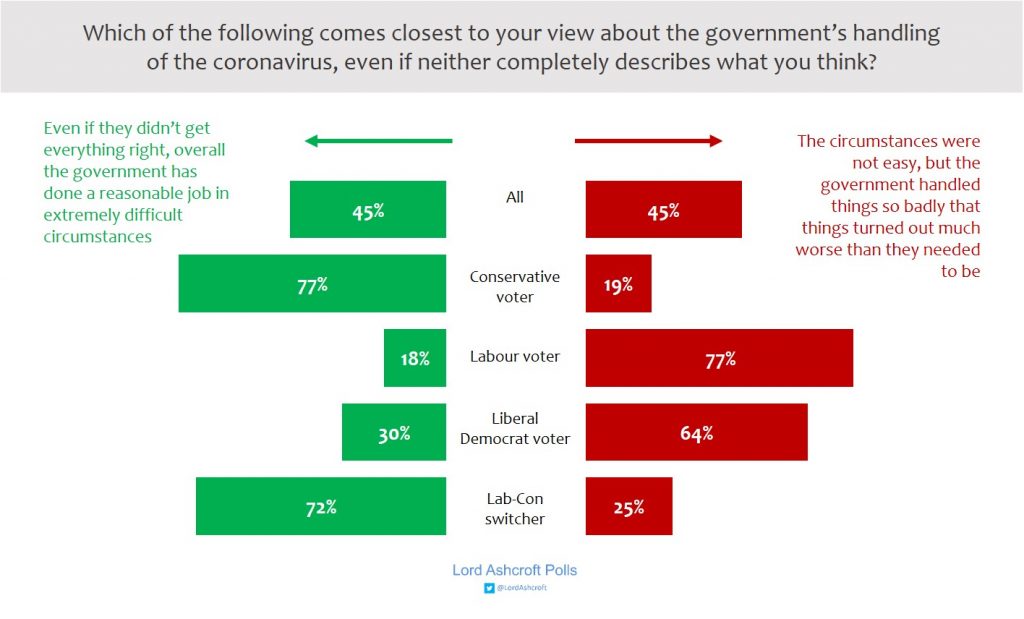

Despite these criticisms, voters as a whole were exactly divided as to whether the government had “done a reasonable job in extremely difficult circumstances” or “handled things so badly that things turned out much worse than they needed to be.” Just under one in five 2019 Conservatives (and a quarter of Lab-Con switchers) took the critical view, while a similar proportion of Labour voters took the generous one. This was reflected in our focus groups, where we often heard comments like “They are trying – I don’t think any government could do more” and “I’m not a fan of the government, but they’re damned if they do and damned if they don’t.” Only one third of voters, and only three quarters who backed Labour in 2019, said they thought a Labour government under Keir Starmer would have done a better job of handling the crisis.

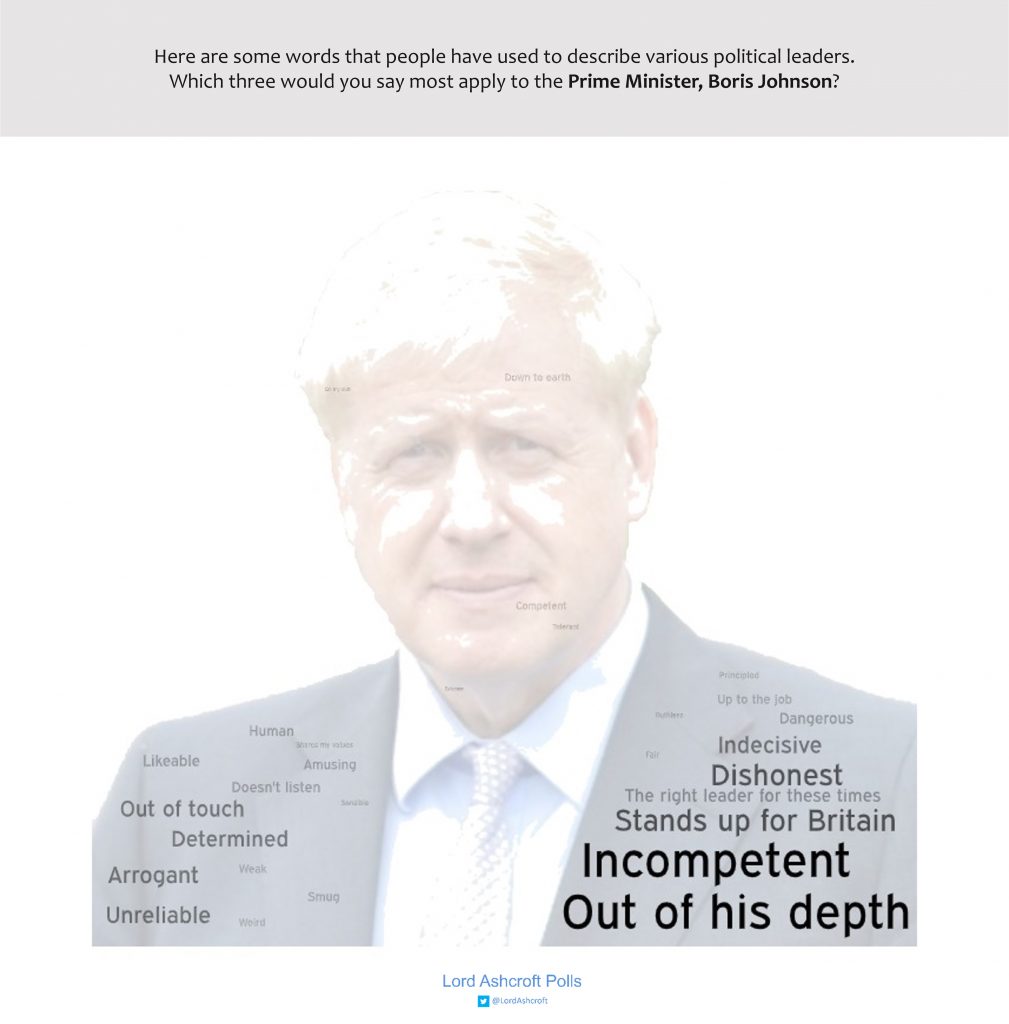

Similarly, there was a good deal of sympathy for Boris Johnson: “he’s in a difficult position but he’s taken on the challenge so we should cut him some slack” was a typical focus group remark. But others noted the crisis had exposed his apparent weaknesses, with some saying he looked “overwhelmed” and “doesn’t seem in control”.

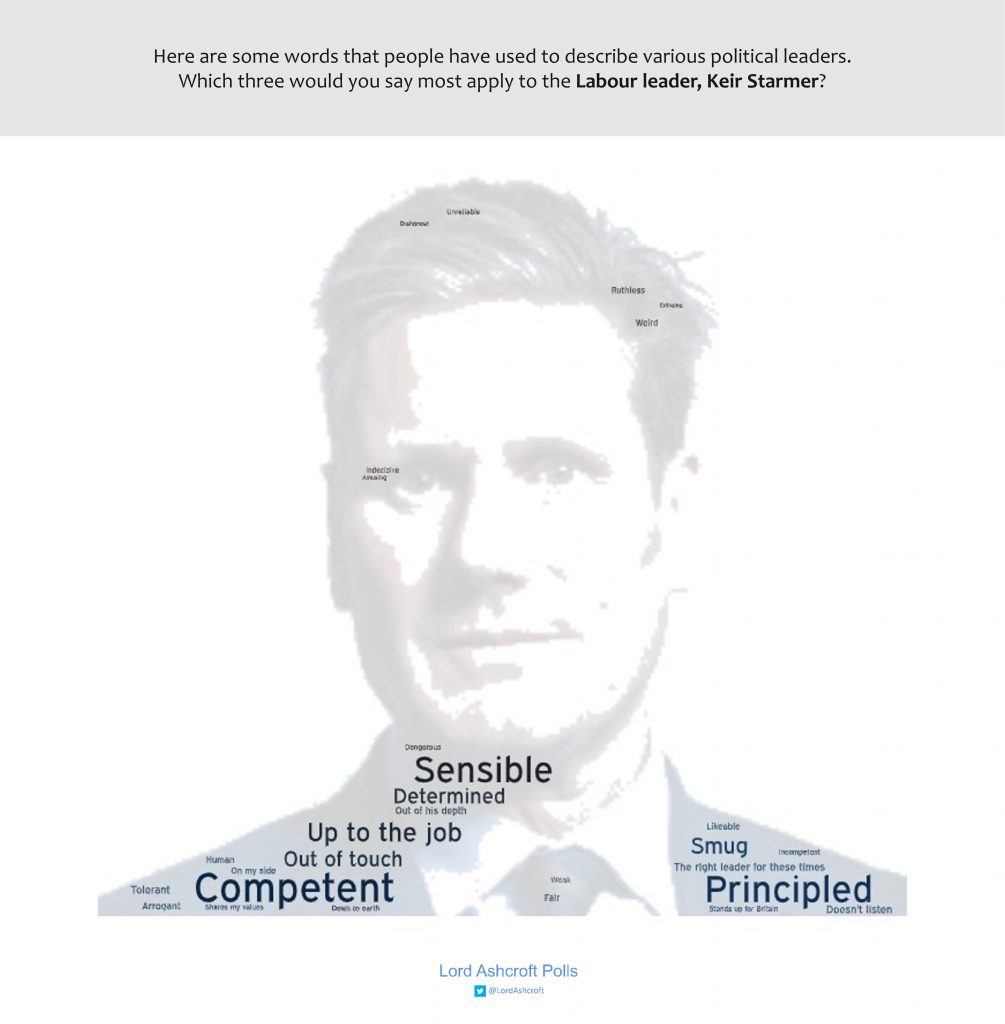

In our poll, the words and phrases most often chosen to describe Johnson from a long list of positive and negative options were “incompetent” and “out of his depth” – though more than one in five selected “stands up for Britain”. The most frequent choice for Keir Starmer were “competent”, “principled” and “sensible”, though more than a third said “don’t know”.

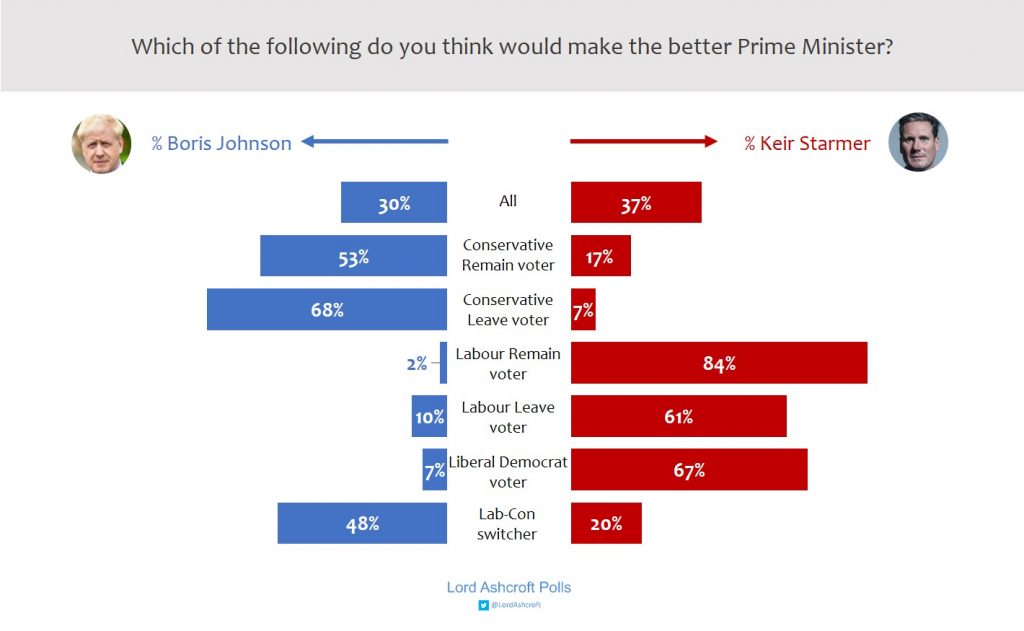

Accordingly, Starmer led Johnson by 7 points on the question of who would make the best Prime Minister. Only just over two thirds of Conservative Leave voters named the present incumbent (a quarter said they weren’t sure), as did and only around half of Conservative Remainers and Labour-Conservative switchers.

Just under four in ten (39%) said Johnson would not be a good Prime Minister whatever the circumstances. Of the remainder, 27% said he was doing a good job, and a further 21% said he could be a good PM under different circumstances but was not the kind of leader we needed at the moment.

Forced to choose between a Conservative government with Johnson as PM and a Starmer-led Labour administration, the latter won out by 53% to 47%. Labour-Conservative switchers still chose the Tory option, but by 69% to 31%.

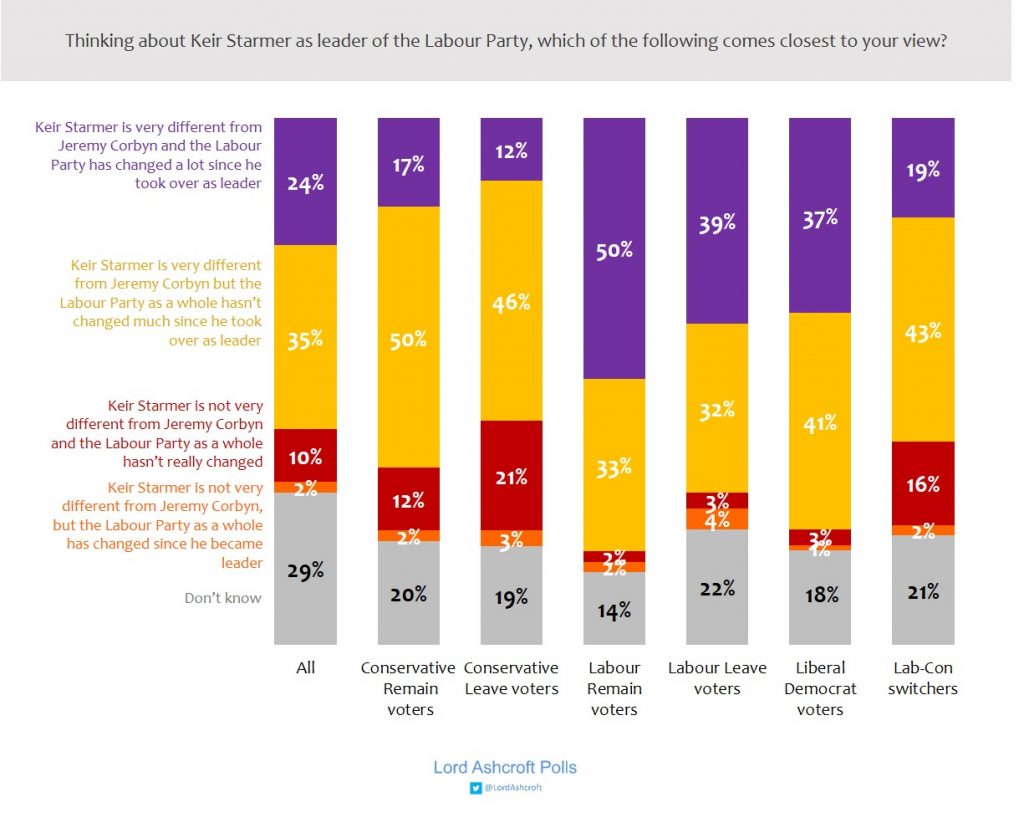

While nearly six in ten voters thought Starmer was very different from Jeremy Corbyn, most of these thought the Labour Party as a whole had not changed much since he became leader. This was particularly true among those who had switched from Labour to the Conservatives at the last election. Starmer had made a good first impression on most in our focus groups, who said he seemed strong, professional and articulate. They also noted that he did a better job than his predecessor of holding the Prime Minister to account, which many attributed to his background as a lawyer. Several said he reminded them of Tony Blair (which they meant as a compliment). However, some wondered how very different from Corbyn he could be, given his willingness to play such a prominent part in his shadow cabinet. Some “red wall” participants were put off by the spectacle of Starmer “taking a knee”, which suggested a willingness to indulge in a kind of gesture politics that they disliked.

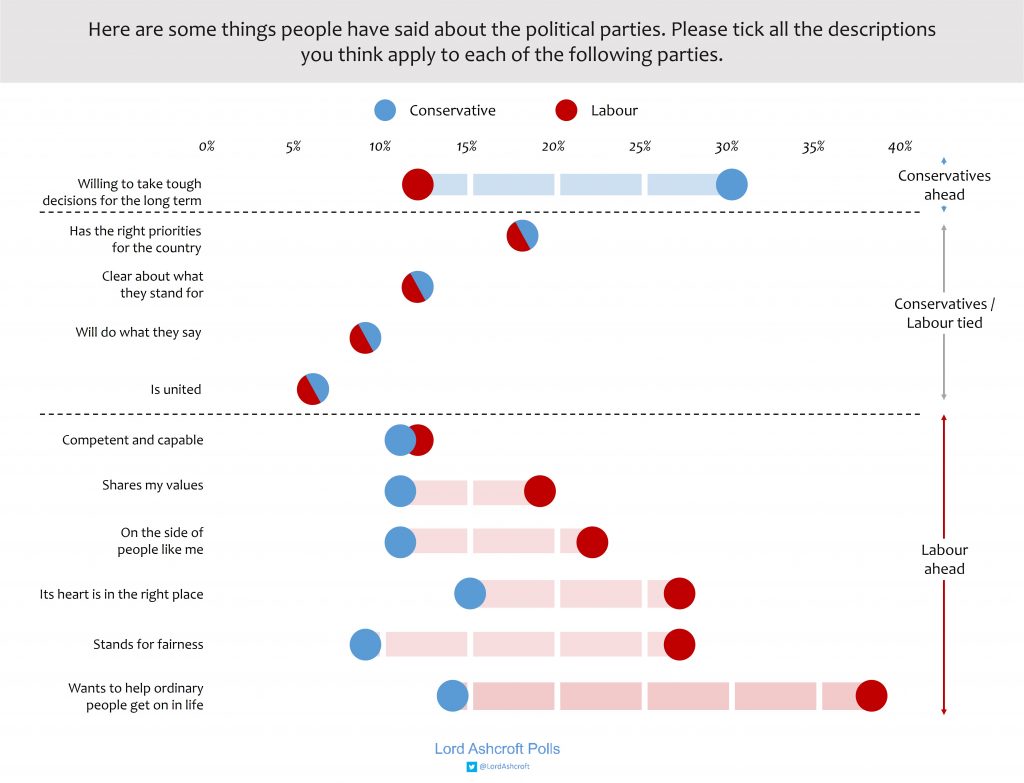

When it came to views of the parties as a whole, the Conservatives led on only one measure – being willing to take tough decisions for the long term. They were tied with Labour on having the right priorities, being clear about what they stand for and being likely to do what they say, and had fallen behind on being competent and capable – all measures on which the Tories led decisively at the last election.

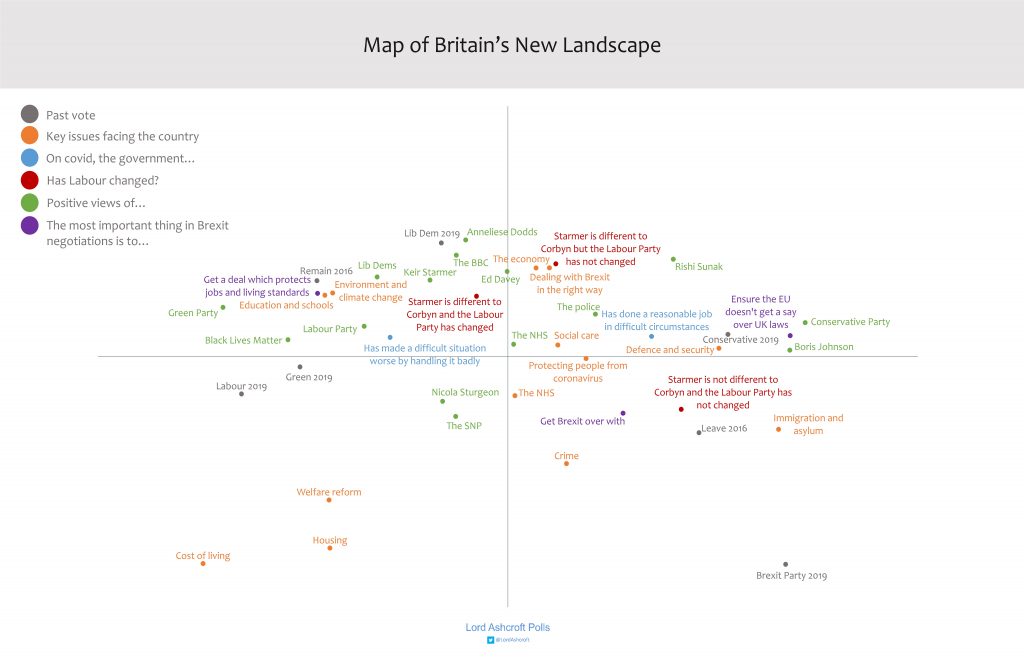

Our political map shows how different issues, attributes, personalities and opinions interact: the closer the plot points are to each other, the more closely related they are. We see that those who think the government has made the covid situation worse by handling it badly are most likely to be found in the already non-Conservative-supporting part of the map. Those who think the government has done a reasonable job in difficult circumstances are more likely to be in broadly Conservative territory, but the view is not confined to the strongest supporters of the Tories and Boris Johnson. The view that the Labour Party has changed since Keir Starmer became leader is most likely to be found close to Labour/Lib Dem territory, while the idea that he is different from Corbyn but the party as a whole has not changed is in the area where Labour and Tory support overlap (where they most need to make progress on this argument). On Brexit, those who feel the priority should be to get a trade deal with the EU are very close to those who voted Remain in 2016. Leave and Tory-voting territory is where we find those most likely to say the priority is to have full control over UK laws – and those who simply want to get Brexit over with.

Crucially, we see that those most likely to mention the economy as an important issue are to be found on the borders of Conservative and Labour/Lib Dem voting territory. That suggests that this will be a crucial battleground in the months to come – over how far the government can and should continue to support businesses and incomes, how the huge spending of recent months is to be paid for, and who is most trusted to rebuild for the future.