Each year Mitt Romney puts together a meeting of ‘experts and enthusiasts,’ the E2 Summit in Utah. This year he invited me to speak about what my research had to say about political disruption in Britain and America, its causes and consequences. This is what I had to say:

In recent years, political change has arrived in some unexpected forms in both our countries, and it’s hard to know what to expect next. I have spent some time trying to make sense of the disruption through my opinion research on both sides of the Atlantic.

This began 15 years ago when, as a longstanding donor to the Conservative Party, I decided it was about time someone made a proper study of why we kept losing general elections – usually after being reassured by the party hierarchy that we were on course for a famous victory. I published the findings under the unambiguous title Smell The Coffee: A Wake-Up Call For The Conservative Party, and on the strength of this, David Cameron appointed me the party’s Deputy Chairman to help ensure its lessons were acted upon. Since stepping down from the role I’ve continued with the research, since it struck me that while commentators were always blessed with an abundance of opinion, real evidence was in rather shorter supply. Another reason was that pointing out the difference between what voters think and what politicians and pundits think they think is an appealing way to create a certain amount of mischief.

On that basis, Mitt has asked me to talk about what my analysis suggests is behind some of the things we have seen in politics in recent years on both sides of the special relationship and what it means for the future. To aid this process, over the last few weeks I have conducted original research in both the UK and the US, including polls of 15 and 30,000 people respectively, as well as focus groups in different places with different kinds of people in both countries. I will publish the full findings in a more detailed report in the next few weeks. This morning, as we look to the 2020 presidential election here and a Conservative leadership election in the UK, I will talk about how we got here, why the values and institutions we take for granted are perhaps more fragile than we care to think, and the lessons for those who hold positions of political leadership or aspire to do so.

It has become a cliché to talk about the polarization that dominates today’s politics. But the problem is not that people disagree, as they always have. The real problem is that for some time, rather than trying to ameliorate those divisions, politics has emphasized and supercharged them.

People often blame Donald Trump for this. But the truth is that he is the latest in a long line of divisive political developments going back at least to the Clinton era. President Clinton’s failed healthcare reforms, the 1994 Republican Revolution, the impeachment, the hanging chads of the Bush-Gore election, the Iraq War, the financial crisis, Obamacare and the rise of the Tea Party have all combined with the rise of talk radio, the growth of cable news, and the explosion of social media to create the political atmosphere we have today.

The UK, where politics has rapidly accelerated into a more advanced state of chaos, has an overlapping recent history of drama: Iraq again, the expansion of immigration from the EU, the scandal over MPs’ expenses, the financial crisis and the years of austerity that followed it, the Brexit referendum and parliament’s inability or unwillingness to implement the result are all part of the backdrop to what we might call the current circus, were it not for the fact that a circus is supposed to be entertaining.

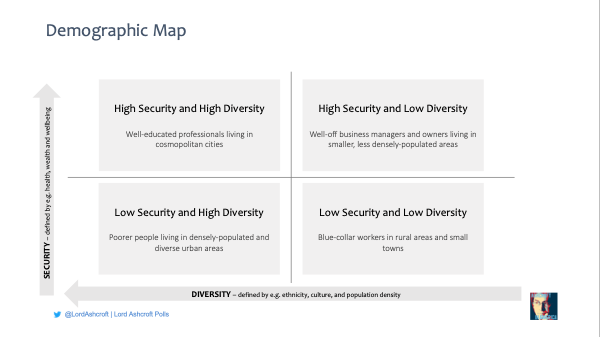

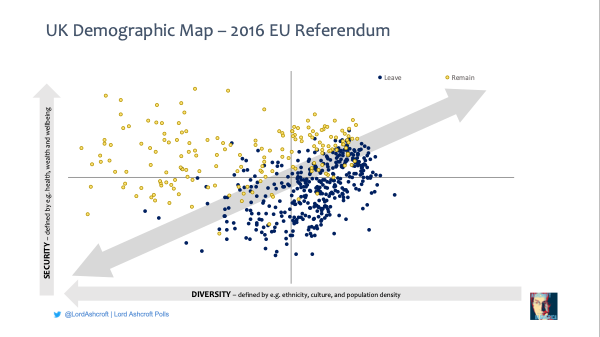

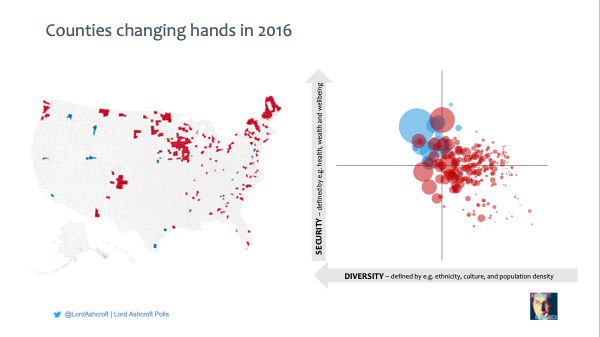

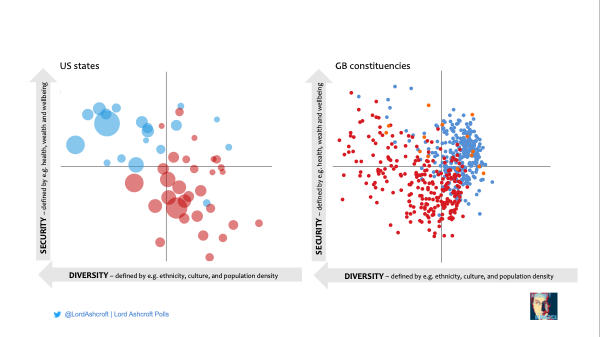

A good way of exploring the effect of these developments, and how dividing lines are moving, is to chart them on a geo-demographic map like this one.

The vertical axis represents security, which includes measures of health, wealth and wellbeing such as income, occupation and education. The horizontal axis represents diversity – a combination of factors including ethnicity, culture and population density. All these measures are derived from census data. By combining this information with election results and poll findings, we can study how opinion and voting behaviour varies – sometimes in unexpected ways – between people depending on their life situation and location.

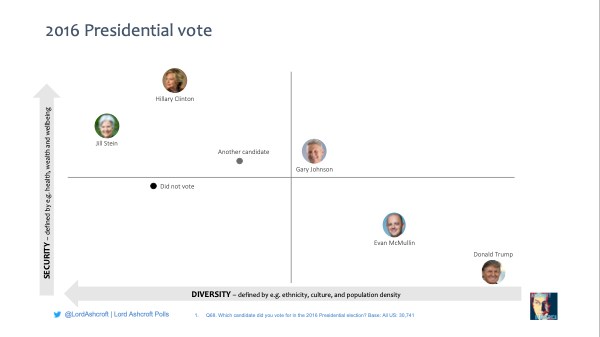

For example, this shows the average position of voters for Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump at the 2016 presidential election. The centre of gravity of the Trump vote is firmly in the bottom right hand corner, where we find ‘low security, low diversity’ voters. The Clinton vote is centred in the opposite top-left quadrant, representing a much more diverse and secure set of voters.

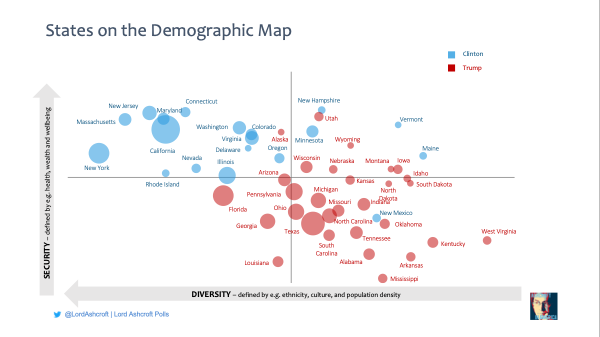

Looked at from a geographic perspective, we can plot states and their relative weights in the Electoral College by their aggregated demographic characteristics. This shows the fault line in American politics in sharper relief, with Democrats dominating the top left, and the bottom right firmly in Republican hands.

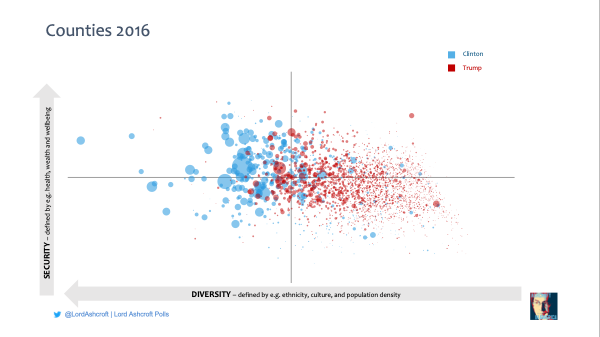

Drill down further still and you get this intriguing piece of modern art. This represents the counties won by the two candidates in 2016. As well as showing the relative size of the local populations in Trump and Clinton territory, it highlights the difference in their character.

But it wasn’t always this way. This is how the Republican and Democrat vote has evolved over the last ten presidential cycles, from 1980 to 2016. It’s not a straight line, but the trend is very clear. In the Reagan era, Republican support was centred squarely in the top right quadrant of the map, among ‘high security, low diversity’ voters. Over time, this has drifted down to the bottom right, as the GOP’s centre of gravity has shifted to less prosperous rural and small-town America. On the other side, the opposite has happened. While always being rooted in more diverse populations, in economic terms the Democratic vote has grown steadily more upscale. In the space of two generations the political fault line in American politics has rotated through 90 degrees.

A look at the divide between political parties in Britain shows a much more Reagan-era pattern to British party support. Here we see the constituencies won by the Conservative, Labour and other parties at the 2017 general election. Conservative seats dominate the less diverse but more prosperous top-right quadrant, with Labour holding all but a handful of seats in more diverse, less well-off territory. The fault line runs from top left to bottom right, which effectively means that poorer, whiter seats and richer, more cosmopolitan seats are often much more heavily contested in Britain than their equivalents in the United States.

But a look at how those same constituencies voted in the referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU shows a pattern that mirrors the divide in American politics today rather than the more traditionally economic battle lines of the Reagan era. In demographic terms, Leave support was centred in the poorer and less diverse parts of the country, with support for Remain heavily concentrated in richer, more urban centres and university towns. In terms of attitudes, the divide over Brexit was much more along cultural lines than along traditional left-right ones.

And this is the root of the problem facing British politics at the moment. The Conservatives won their unexpected majority in 2015 by building a coalition of support around their programme to cut the deficit and stabilize the public finances. Two years later, Theresa May called an early general election on an issue that divided the country in a completely different way, in the hope of reassembling the Brexit-voting coalition under the Tory banner.

Instead, she got the worst of both worlds. Many Remain voters deserted the Conservatives because of Brexit. But most of the Leave-voting former Labour voters who were supposed to take their place refused to fall into line with what they saw as the party of cuts. Wild horses wouldn’t get them to abandon their tribe and vote Tory, however much they supported Brexit. The result is the hung parliament, and the resulting deadlock over Brexit that we have seen ever since.

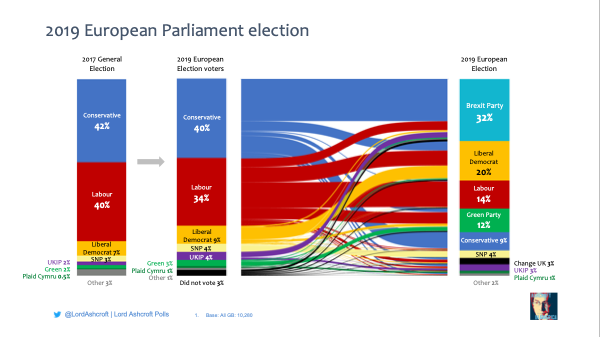

So now we have both main parties struggling to keep their respective voting coalitions together while trying to negotiate their way through Brexit. The compromise, incoherence and disappointment generated by their efforts was obvious when the British public was given the unexpected and largely unwanted opportunity to vote in the elections to the European Parliament two weeks ago.

As my polling on election day found, more than half those who voted Tory at the general election and turned out at this election switched to the Brexit Party, and a further 12% went to the pro-Remain Liberal Democrats. Only a minority of those defectors currently say they will go back to the Tories at the next general election. The clear lesson from all this is that the Conservatives cannot go into the next election with Brexit still unresolved – but that in the current parliament there has been no majority for any solution. In other words, a new leader is not by itself the answer to the Tories’ problems, as the lucky winner will quickly find out when he or she enters Number Ten next month.

To return to the drama on this side of the ocean, we are currently at the stage in the political cycle that might be called the Candidate Backstory Season. We are constantly hearing that someone running for office is a gay veteran, or partly Native American, or is the best qualified candidate in history and wants to be the first woman president. It’s fine to be any or all of those things, of course, as long as we remember that theirs is not the story that really matters. Candidates are supposed to pay attention to the voters’ backstory, and candidates who think it’s the other way around will come unstuck, as many supposed front-runners have found to their cost.

And what is the voters’ backstory in the run-up to 2020? Clearly it depends on the voter, but my research reveals some common themes.

Many voters are living through a time of unease and anxiety. This is not confined to one side of the political spectrum, nor to the lower end of the income scale. People feel that it’s harder than ever before to stay middle class. The cost of healthcare, how to pay for college, how to fund their retirement with no defined pension, the fear that social security will disappear before they need it, the seeming impossibility of buying a house anywhere they would want to live, and the accelerating trend of jobs being outsourced or automated are constant themes in my research. This is true even among those who are fairly comfortable on a day-to-day basis and who acknowledge that the economy is growing.

Moreover, people don’t see how these things will improve over time. Incomes are not keeping pace with outgoings, and many wonder whether their children will be able to enjoy the kind of life that they have. Though the American dream is still there, especially for immigrant families coming to the US for the first time, we hear time and again that it is becoming more of a struggle for people to attain the kind of life they aspire to.

All of this makes many people wistful for their parents’ generation when, to hear them tell it, people enjoyed loyalty from their employers, affordable college, guaranteed pensions, more family time, and a simpler life with less to worry about. A time when one income would buy a house and a comfortable family life. They acknowledge improvements too, of course, but in both our UK and US research people of all kinds are quite ambivalent as to whether life in their country today is better or worse than it was 30 years ago.

The political atmosphere is only heightening this sense of unease. The relentless pace of politics, and the constant barrage of news, information and misinformation, brings its own angst. People are finding their political views becoming stronger as they react to events and respond to what they hear from the other side. At the same time, many feel they are having to become more guarded about what they actually say, with people ever more ready or even eager to take offence. All of this adds to the sense of division that people are constantly being told is the hallmark of national life in both our countries.

What all of this goes to show is that Brexit in the UK and the rise of Donald Trump in America were a long time in the making. It is easy to forget that they are symptoms, not causes. And by the same token, things will not simply change back once the current cast of political characters leaves the stage or when Brexit is settled, if it ever is. What Warren G. Harding called a “return to normalcy” is not on the cards any time soon.

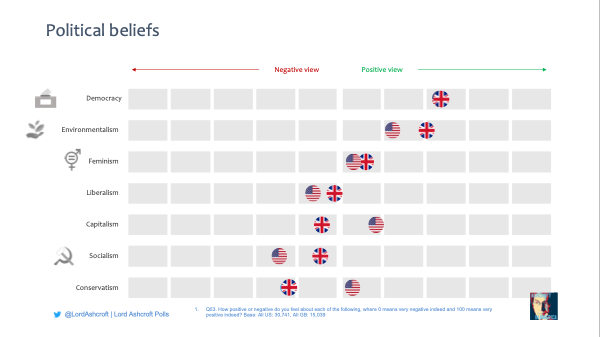

Another symptom of this discontent is that people are increasingly questioning some of the foundations of the political and economic system most of us have grown up with and taken for granted.

Take capitalism itself. In the US, I found capitalism still regarded more positively than socialism – but among Democrats, socialism has the edge. In Britain, the two ideas are neck and neck, though among Labour voters, socialism is comfortably ahead.

While most Americans still consider capitalism an appealing idea, only 43% – and only just over one third of Democrats – say they think it works in practice. And a quarter of Americans who think capitalism is effective nevertheless find it an unattractive idea. All of this is tied up with the insecurity, lowered expectations and the growing struggle to stay middle class that I was talking about earlier. It provokes the thought that if the justification for capitalism is going to be that it’s brutal but it delivers the goods, then it had better damn well deliver the goods.

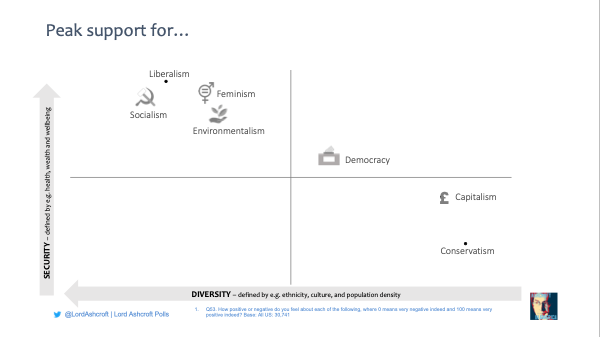

Our demographic map shows where to find peak support for each of these concepts. The striking thing about this is that anyone who thinks socialism in America finds its greatest appeal among the poor and dispossessed would be quite wrong.As we can see here, the average position of those who feel very positive about socialism is squarely in the cosmopolitan top-left quadrant. That is not to say that across the board, better off people are more inclined to be socialists. What it does mean is that if you were hunting for socialists, a good place to start would be in a diverse, metropolitan enclave of a big city in a liberal state, and among people who – to editorialize slightly for a moment – can afford to think socialism sounds like a good idea. You might almost say that the idea of overthrowing American capitalism is most popular among people who have done rather well out of it. This, in a nutshell, is why income and class are no longer a sufficient explanation for what happens in politics, if they ever were – an observation that takes us neatly into the topic of the next presidential election.

To return to our demographic map, here are the states that changed hands at the last election in 2016. As you can see, they are all close to the centre, and along the line that separates the cosmopolitan, liberal top left from the more conservative and less diverse bottom right.

The point is made even more starkly when we look at the individual counties that flipped one way or the other. If the familiar map on the left shows where these places were, the one on the right shows what they were like, and where the divide falls. In geographical and demographic terms, this is where the battle for 2020 will once again be played out.

In political terms, we know what one side is going to look like. My research has consistently found most of those who voted for Donald Trump saying he has met or exceeded their expectations. They point to a thriving economy, which they put down to his tax reforms and deregulatory agenda, conservative appointments to the Supreme Court, a firm stance on immigration and border control and what they see as his determination to stand up for America in the world. And while his opponents spent the last campaign and much of his presidency complaining about his personal conduct, even those who voted for him only reluctantly tend to see this as a price worth paying for someone who is keeping his promises, shaking things up in Washington and standing up for them.

But there are Republicans voters in play. These are most likely to be found among those who switched to Trump having previously voted for Barack Obama; those who voted for him only grudgingly in order to stop Hillary Clinton; those who couldn’t bring themselves to vote for either candidate in 2016; and the moderate suburban voters who switched sides or stayed at home in last year’s midterms to give Democrats control of Congress.

And as I mentioned earlier, there is a weariness with the relentless rancour and division that has come to dominate politics in America, and which President Trump is not exactly setting out to soothe.

The question is, will the Democrats grasp the opportunity this presents? The evidence here is mixed at best.

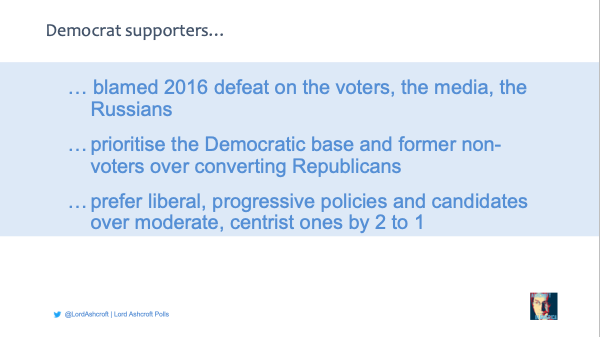

In a survey after the 2016 election I asked Clinton voters why they thought they had lost. First, they blamed the voters, for not understanding the issues that were at stake. Next, they blamed the media for failing to hold Donald Trump properly to account and for disseminating fake news. After that, they blamed the Russians. The Clinton campaign, or the candidate herself, came very low down their list of reasons for defeat.

When I asked Democrats last year what they thought their campaigning priority should be, a clear majority thought it was more important to motivate and enthuse their base and turn out non-voters than it was to understand and reach out to people who have recently voted Republican.

Later, after the midterm elections in November, I asked in more detail about the kind of approach they wanted for 2020. Given the choice, a clear majority of Democrats said they wanted to see more liberal, progressive policies and candidates. Fewer than three in ten said they wanted the Democrats to take a more moderate, centrist direction.

The risk for the Democrats here is obvious. If President Trump is not exactly a unifying figure, picking his polar opposite is not the obvious way of building a majority coalition. Voters as a whole, and especially independent voters, put their likelihood of supporting a moderate centrist Democrat higher than that of supporting a progressive liberal.Or as one of our sage focus group participants put it, “most Americans are between the 40-yard lines”, even though the parties and most political debate seem to be dominated by the two end zones. There are voters with no great love for President Trump who will back him again if the alternative seems too extreme. In other words, it’s easy to see how, in their fury with Trump, the Democrats could end up nominating someone who turns out to be his antithesis but not his nemesis.

But so much for the hypotheticals. Let’s look at how people are reacting to some actual candidates.

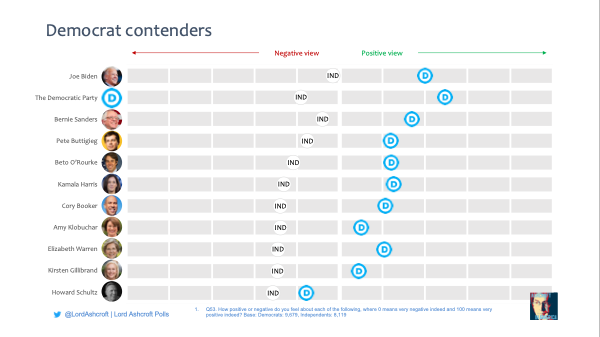

This is how the top contenders lined up among Democrats and Independents when I asked about them in my poll last month. This of course comes with the proviso that at this stage, much of this is name recognition and that most normal people have better things to do than follow the twists and turns of the primary process before it has even properly started. Indeed, for all the candidates on this list apart from Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, at least half of respondents said they had no opinion.

For convenience, I’ve also included Howard Schultz here. The evidence is that he has yet to make the impact he hoped, rating lower even among independent voters than all the Democrat candidates we tested. Anecdotally, it was striking in our recent focus groups that people in different places said spontaneously that although they admired his story as a businessman, they didn’t quite trust his motivation in running for president. There was also a feeling that, as one put it, “this election cycle is pretty do or die,” and backing an independent candidate could only help Donald Trump. Even so, with 63% saying they had no opinion of him yet, Mr. Schultz may feel he still has time to make his presence felt.

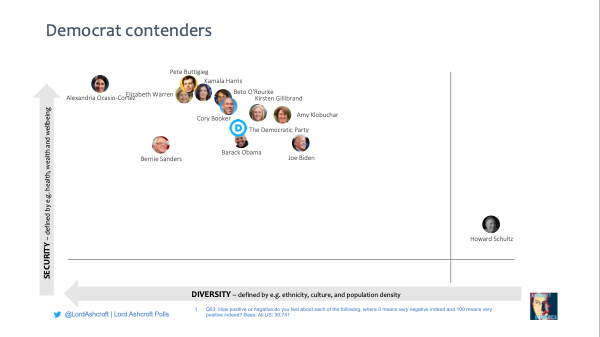

More interesting at this stage is where on our demographic map to find the strongest backing for each of the candidates. I know the formidable AOC is not running, at least not this time, but it’s instructive to see where her peak support lies in relation to the contenders. Joe Biden clearly has the most mainstream appeal at this stage of the game. And as we saw in the previous slide, he is the only Democratic candidate who currently rates higher than the Democratic party as a whole.

But as our polling showed, he is not the candidate committed Democrats want in theory. And as has been clear from our recent focus groups, they are wrestling with the question of whether he’s the candidate they want in practice. They know that in 2016 they had a nominee who infuriated their opponents and alienated too many undecideds without enthusing their own base. They also know the trick is to have it the other way around – someone who can excite their party while being approachable enough to reach into marginal territory, or at least not galvanise opponents into voting when they might otherwise stay at home. And though many moderate and independent voters we spoke to saw Biden as a welcome return to calm and normality – and many Republicans saw him as the biggest threat to Trump – Democrats were not yet ready to settle for that compromise. He was described to us variously as “too indebted to big corporations,” “part of the establishment,” one of “the wealthy crony crowd,” and another “rich old white dude.” If his team are hoping that some of the Obama stardust has rubbed off on him, I fear they are mistaken. That’s not to say the Democrats won’t ultimately pick him – but if they do it will be as a fallback, and at this stage they seem eager to be convinced it’s a compromise they don’t have to make.

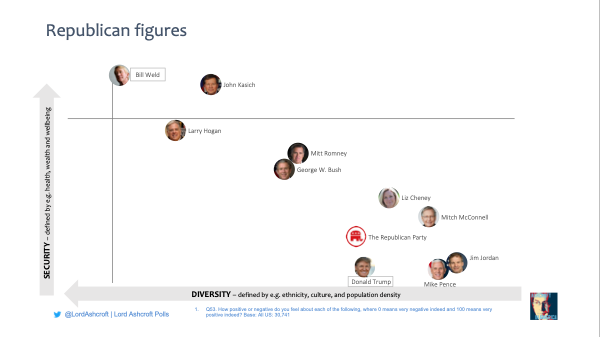

On the other side of the aisle, we can see what kinds of voters have very positive views of various Republican figures. President Trump and Vice-President Pence are in the far bottom right corner, with President Bush, John Kasich and our esteemed host finding their highest ratings among voters who are somewhat further up the scales of diversity and security. Tellingly, support for Governor Weld is some distance not only from Donald Trump’s, but from the centre of gravity for the Republican Party as a whole, suggesting he will find it an uphill struggle to convert the GOP electorate to his cause in his primary challenge.

How to draw these threads together? The most recent casualty of today’s bitterly divided politics has been Theresa May. She said when announcing her departure that compromise is not a dirty word – and so it isn’t, but nor will it do as an answer to what is going on in today’s politics. If politicians and parties are less willing to compromise, it’s because voters are too. In an age where people can increasingly have whatever they want whenever they want it, and want their choices as consumers to reflect their personal priorities and values, they are more and more reluctant to make the kind of concessions and accommodations that politics demands. “The parties don’t reflect the paradigm of my life,” as a woman in one of our focus groups quite literally put it to us last month.

This is especially true when the politics people see played out on the news each day seems inadequate to, or even completely divorced from, the practical problems that confront them in their daily lives, and the anxieties they have about their family’s future.

And it goes double when politics is conducted on the lines we see in America and are increasingly seeing in Britain. When politics is mainly cultural, it becomes a zero-sum game: you can only be winning if the other side is losing. There is no trickle-down effect in the culture wars, nor any sense that a rising tide lifts all boats. The idea of governing for everybody, of politics as win-win, has taken a back seat. The only people for whom politics is win-win are the elites, who always seem to win whatever the outcome, while the rest continue to struggle. That makes people feel less invested in the process, and less sure that they have a stake in it. So you can win by emphasising these divides – but only for a time, and only at the cost of undermining support for the values and institutions on which all else depends.

What is the antidote to all this? The clue once again lies in our map, and with a lesson from history.

The most successful politicians in our era have been the ones to build the biggest and most enduring coalitions of voters. Not to identify divisions and exploit them, but to put their principles to work for the benefit of people in all corners of the map. And if that sounds a bit soft and fluffy, let me say that the two leaders I have in mind are Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher – people of undoubted conservative conviction who kept pace with social and cultural change without alienating their core supporters, and who showed people who had never before voted for their parties that there was something in it for them. It’s a lesson that the next generation of leaders on both sides of the Atlantic would do well to heed.

Thank you very much.