My presentation to the International Democrat Union executive meeting in Santiago, Chile, looking at what my polling shows about the prospects for the 2020 US Presidential election.

Since the midterm elections in November I have conducted further research looking at the state of play at the midway point in Donald Trump’s term – or should that be his first term? This is presented in detail in my latest book, Half-Time!, which also brings together more than two years of my work on the Ashcroft in America project. The aim is to work out where the American public is and where is seems to be heading as the battle lines are drawn for the 2020 election. I will set out some of the main points here, but do take the chance to help a struggling author and get hold of a copy either from Amazon or direct from Biteback Publishing.

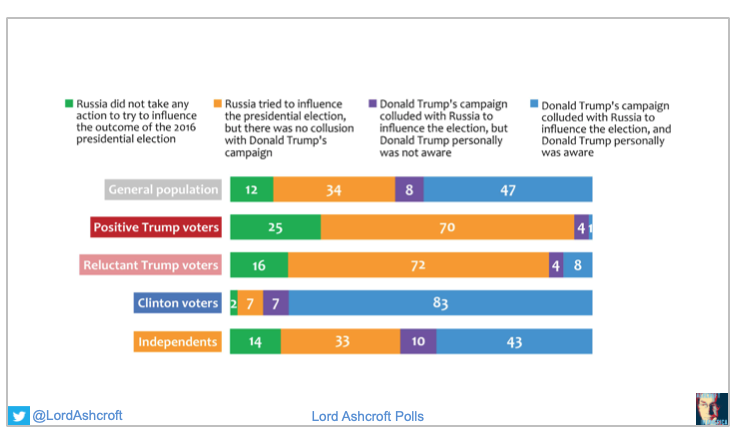

I should say at the outset that there have been a few developments since the work I’m going to talk about was completed. One of these is the announcement that the Mueller investigation has found no evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia during the 2016 election.

This is clearly a major news story and one that has been greeted with euphoria in the White House, with dismay by Democrats, and with a degree of soul searching in the media. But it probably makes little difference to the next election except to guarantee that Donald Trump will be free to take part in it.

As I found last September, nearly all Republicans believed Trump was innocent and that the investigation was a ‘witch hunt’, and nearly all Democrats believed he was guilty – indeed, Democrats thought the Mueller investigation was the main thing the Trump presidency would be remembered for in 20 years’ time. In other words, whether or not you thought Donald Trump colluded with Russia depended on whether or not you had voted for him in the first place. So unless we are going to see large numbers of Democrats suddenly declaring that he’s been vindicated so they’re now on his side, I doubt this will do much to change the fundamentals. Unless, of course, you count the opportunity cost to his opponents of spending two years speculating on links to Russia when they could have been doing something more productive.

The other main political development since this research was done is that nearly every Democrat you’ve ever heard of, and several that you haven’t heard of, has decided to run for President. At this stage, my purpose is not to talk about the candidates, but the electorate that will make the decisions. First, some of the big picture themes that I think will matter over the next 18 months.

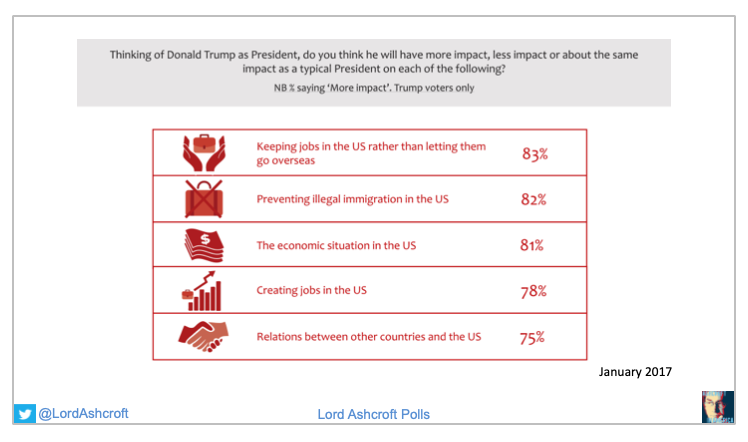

I called my analysis of the 2016 election Hopes and Fears, and that is still a good framework for looking at current American politics. To begin with the hopes, here are the things on which Trump voters expected their man to have the most impact at the time of his inauguration. As you can see, the list is dominated by the economy: keeping jobs in the US rather than letting them go overseas, creating new jobs, and the overall economic situation. They also expected Trump to be more effective than most Presidents when it came to preventing illegal immigration, and in relations between the United States and other countries.

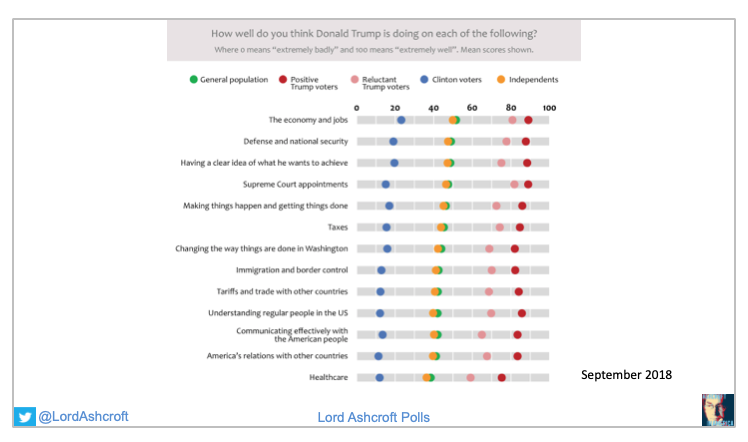

As far as most of his supporters are concerned, Trump has met or even exceeded expectations. Top of his list of achievements comes the economy, whose performance they readily put down to the administration’s policies on tax cuts, deregulation, and a willingness to reshape global trade deals in America’s interests. Just before the midterms we found nine in ten Trump voters saying they expected the economy to do well over the next year both for the country as a whole and for them and their families, and in focus groups since the election, the thriving economy has always been among the first things mentioned by voters when asked about President Trump’s achievements. We even find people who were very doubtful about Trump in 2016 but who have changed their mind, such as the driver in the construction industry who told us in California that his work had tripled since Trump took office: “I thought he was a joke, but maybe a businessman is what we needed,” was his conclusion.

The President also receives very high marks on defence and national security, immigration and border control, and his combative approach to international affairs. He also scores very highly among his voters for his appointments to the Supreme Court – indeed this comes top of the list for those who voted for him only reluctantly. As we found during the 2016 campaign, his promise to appoint conservative judges helped to turn out Republicans who were uneasy about their nominee, and they acknowledge a promise delivered.

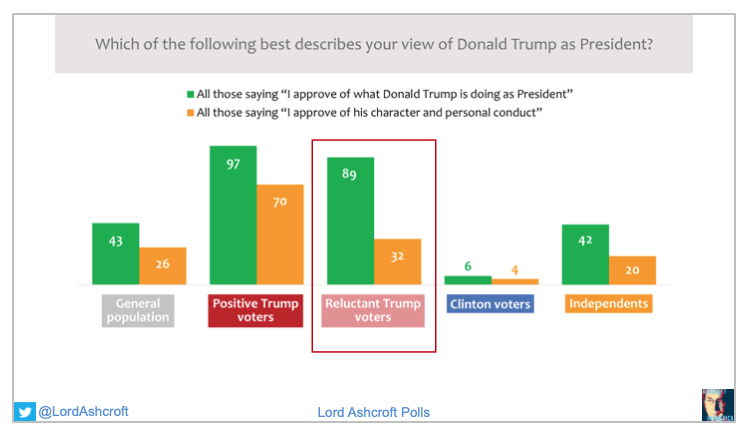

It is also important to reiterate that while much of the criticism of President Trump from the campaign onwards has focused on his personal conduct, a significant section of the electorate consciously separated his behaviour from his policies and actions, and they still do. We found last autumn that while seven in ten of those who voted positively for Trump said they approved both of what he was doing as President and of his character and personal conduct, this was true for only 31% of his more reluctant backers. However, more than half of this group said they approved of his actions not his character, meaning that nearly nine out of ten reluctant Trump voters approved of what Trump was doing as President.

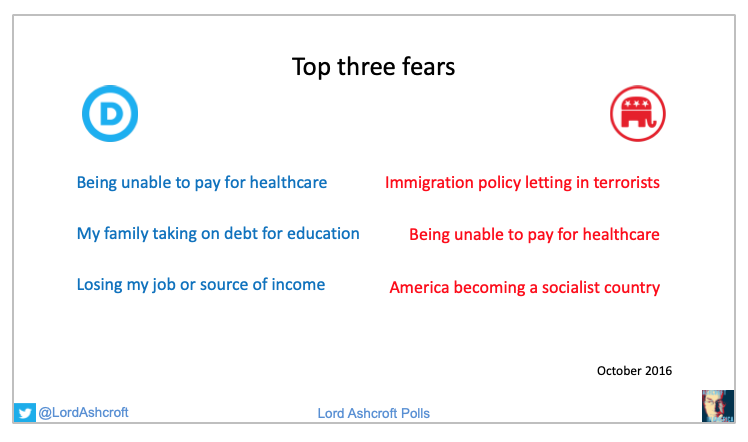

But delivering on hopes and expectations is only one side of the story. Fears are likely to play at least as great a part in the coming battle, and here again it is worth going back to the start. During the 2016 campaign we asked 30,000 voters how afraid they were that particular things might happen, and the answers help to explain a good deal about the politics of the last two years and the campaign to come.

For voters as a whole, and especially for Democrats, the single biggest fear was not being able to pay for healthcare if they or a family member became seriously ill. The second biggest fear, and the one that topped the list for Republicans, was immigration policy allowing people into the United States who threaten their community.

This has been a continuing theme. Republicans voting in the midterm elections told us the policy issue most on their minds was immigration; for Democrats, it was healthcare. With the President prepared to endure the longest federal government shutdown in history over funding for his Mexican border wall, and with the administration supporting efforts in the federal courts to strike down Obamacare, the two principal fears on both sides of the aisle look set to play a big part in the race to 2020.

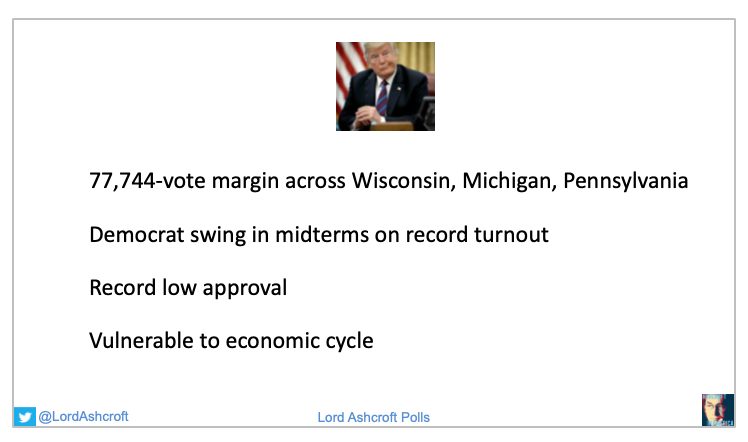

Where does all that leave President Trump as he looks to the next election? With a devoted base every bit as solid as it was when it cheered his victory, and an opposition movement that seems to become more riled and determined by the month. And despite delivering for his base, there is no doubt that his position is potentially vulnerable. His victory in the Electoral College famously relied on fewer than 78,000 votes spread over three states. November brought the highest turnout in over a century, with the vast majority of districts seeing a swing to the Democrats – who received almost as many votes in a mere midterm as Trump did in the presidential election. They took back not just the House of Representatives but seven Governors’ mansions and hundreds of seats on state legislatures, while the Republicans lost a Senate seat in Trump-voting Arizona and got a run for their money in Texas and Mississippi, having mislaid another seat in deep-red Alabama the previous year. Any political support that depends on a strong economy is vulnerable to the vagaries of the economic cycle. And Trump’s overall approval rating has been lower for longer than any recent President who went on to be re-elected – as well as some who didn’t.

But 2020 will be an election, not just a referendum on the incumbent. A huge amount depends on his opponent and their message – and if that sounds like a statement of the obvious, in this election it will be truer than ever.

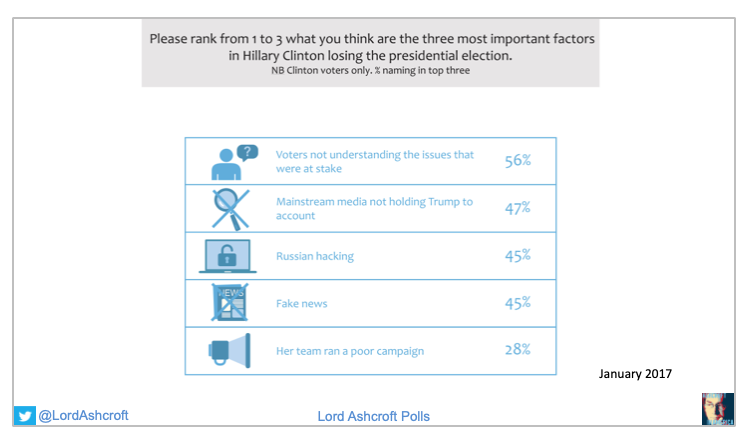

For some clues about how the Democrats are approaching this process, it’s worth reminding ourselves why they thought they lost in 2016. It was a natural enough response to defeat, and one we will all have seen in our own countries, and probably, if we are honest, in our own parties.

First and foremost, they blamed the electorate – more than half put “voters not understanding the issues that were at stake” in their top three reasons for the outcome. Next, they blamed the media – nearly half said the media failed to hold Trump properly to account, and nearly as many blamed “fake news”. After that, they blamed the Russians. Only just over a quarter thought the Clinton team ran a poor campaign, and only one in five put the result down to their candidate – Democrats were nearly as likely to blame misogyny and racism as they were to put it down to Hillary Clinton herself. It may be that mature reflection has brought a deeper understanding of what went wrong for them, but if so, I haven’t seen a great deal of evidence for it.

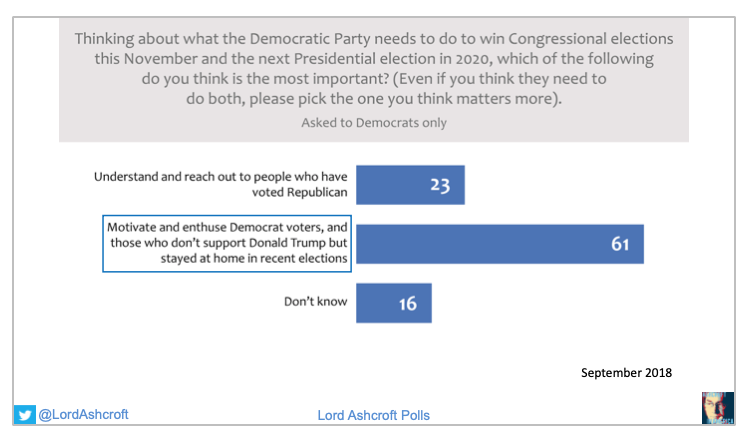

We also have more recent evidence on what Democrats think they need to do to win. When we asked last autumn what they thought their campaigning priority should be, less than one in four Democrat identifiers said the most important thing was to understand and reach out to people who have voted Republican in the last few years. A very clear majority thought it more important to motivate and enthuse existing Democrat voters, and those who don’t support Donald Trump but stayed at home in recent elections.

It may be that Democrats feel vindicated in this view given their recent victories in elections where they have been able to raise turnout. Even so, it would be a brave strategy to decide they need not convert any of the President’s voters, on the basis of elections in which Donald Trump himself has not been on the ballot.

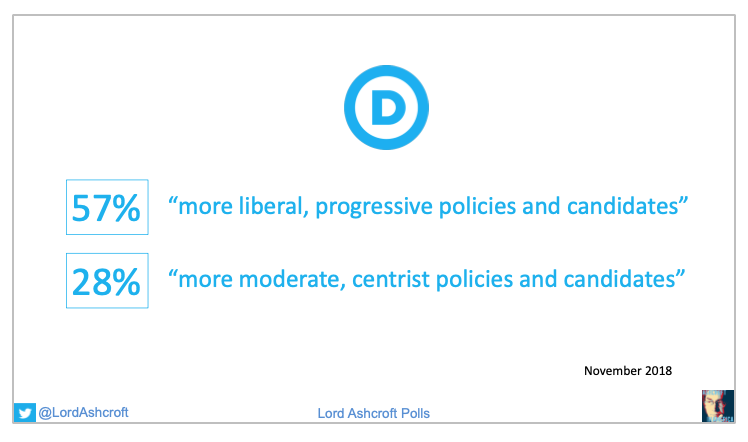

In my most recent polling, after the midterm elections in November, I asked in more detail about the kind of candidate and approach they wanted for 2020. Given the choice, a clear majority said they wanted to see “more liberal, progressive policies and candidates.” Fewer than three in ten said they wanted the Democrats to take a “more moderate, centrist” direction. And crucially, as we will see, the more committed they are to the party, the more likely they are to feel this way.

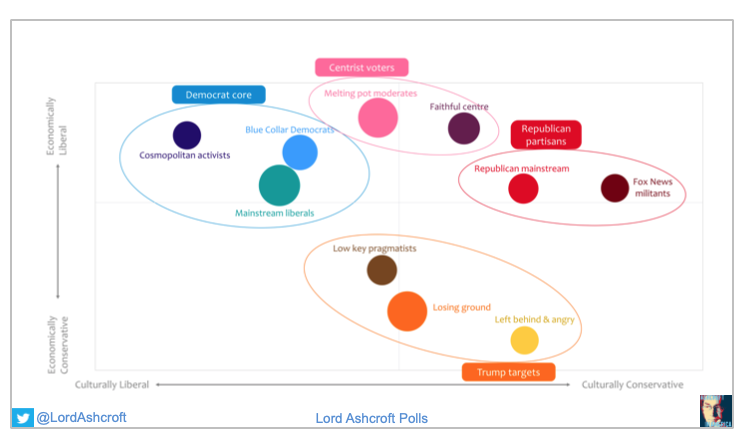

Our 2016 analysis identified ten distinct segments within the American electorate. Towards the left we found three groups who between them make up what we call the Democrat Core. These are the Mainstream Liberals, the more working-class Blue-Collar Democrats, and a smaller group of highly motivated and politicized voters who we called the Cosmopolitan Activists. All three are in the top left quadrant here, showing that they are both culturally liberal and relatively economically liberal, in the sense of being more comfortable with globalisation and international trade.

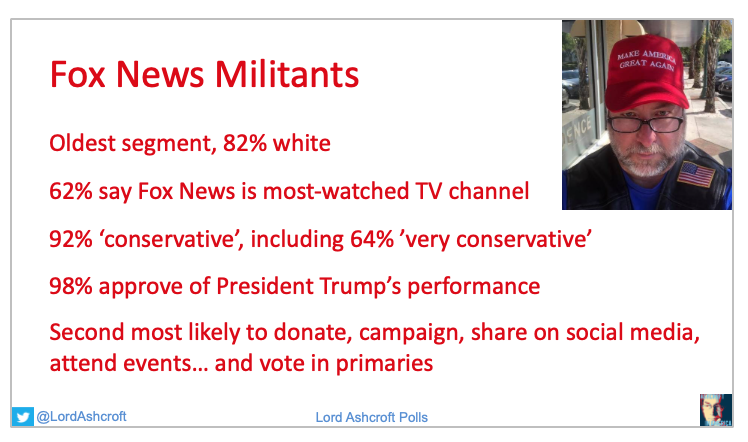

On the other side we have the two groups that make up our Republican Partisans, namely the Republican Mainstream and the most culturally conservative of all, the Fox News Militants. We also have two groups of centrist, less partisan voters, and a cluster of dissatisfied and traditionally less politically engaged voters, many of whom Donald Trump managed to target successfully in 2016.

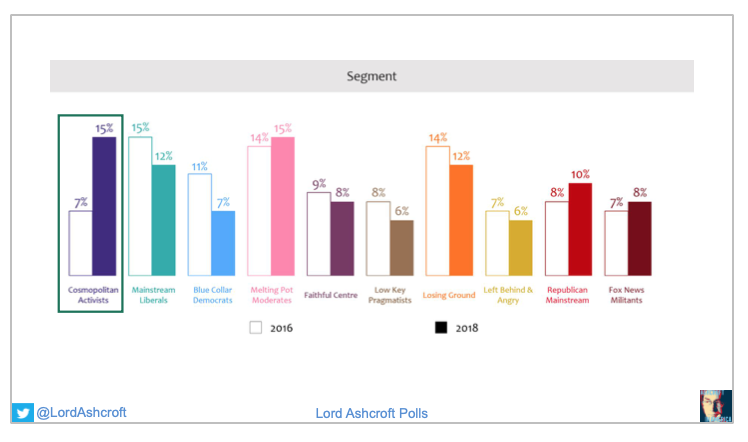

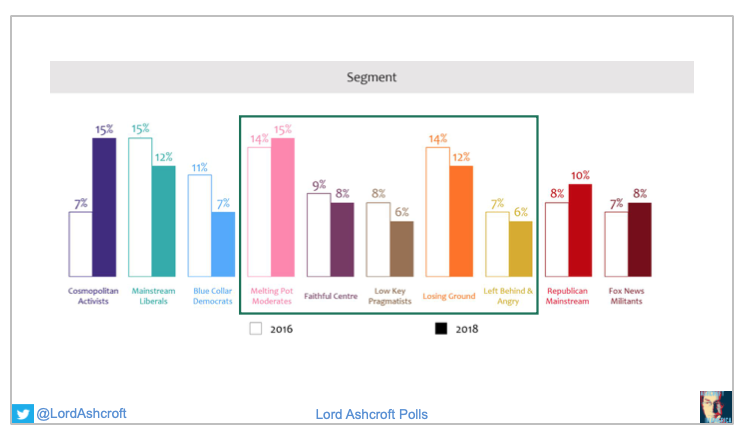

When we repeated the exercise after the midterms in November we found the size of these groups to be fairly stable, which is at least reassuring from the point of view of our poll sampling. But there had been one significant change in the two intervening years, and it occurred on the left. The Mainstream Liberals and Blue-Collar Democrats had shrunk, while the more radical Cosmopolitan Activist segment had more than doubled in size to become dominant group within the Democrat Core.

I think this is interesting for two reasons. First, it tells us something about the Democratic movement’s response to the Trump presidency. In our focus groups towards the end of last year we heard people who had previously considered themselves moderates describe how they had been driven leftwards in reaction to Trump and all his works. The perpetual horror at the President’s words and deeds, especially on social media, has had the effect of radicalizing formerly mainstream opponents, who now feel less inclined to seek moderation and consensus.

Second, it tells us something about the kind of contest that could unfold over the next 18 months.

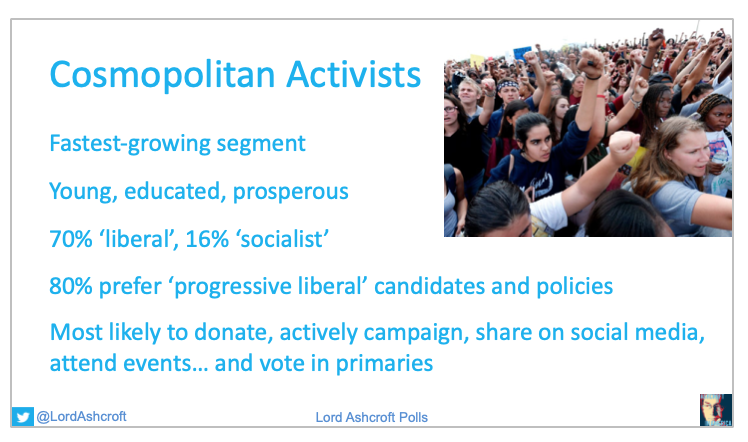

Members of the Cosmopolitan Activists segment are disproportionately likely to be young and female. They are the most likely of all the groups to have a college degree, and to earn over $150,000 a year. Interestingly, they are also the most likely to be white outside the Republican-leaning groups. Seven in ten describe themselves as liberal, including 43% who say they are ‘very liberal’, and a further 16% describe themselves as ‘socialist’. 98% of them voted for Democrats in the House election last November.

They are the most positive about immigration, same-sex marriage, gun control, legalisation of marijuana, government regulation to protect workers and the public, and investment in green energy to combat climate change. In 2016, more than four in five of them said they believed life in America was better than it was 30 years ago. That is now down to just over half – another indication of how their outlook has changed in response to the Trump presidency.

They overwhelmingly want the Democrats to adopt progressive, liberal candidates and policies rather than moderate, centrist ones, and indeed regard being a progressive liberal as the most important feature of the party’s next presidential nominee.

At the other end of the spectrum we have the Fox News Militants. Nine out of ten of them describe themselves as conservative, including two thirds who say they are ‘very conservative’. They all but unanimously approve of President Trump’s record, are the second most likely to take part in political campaigns after the Cosmopolitan Activists, and are the most likely of all to vote in the Republican primaries. Most of them say that Fox News is their most-watched TV new channel. They have the most negative views about immigration, free-trade deals, same-sex marriage, gun control and big government, think judges should interpret the Constitution as written, and think religion is wrongly being driven out of American life.

But for all the well-documented polarization of American society, not everyone falls into one of these two camps. There remains a large swathe of voters who do not have anything like the same degree of partisan zeal. Those in the five segments outside the two party cores tend to be less strident in their views on social and cultural issues, and take a more balanced view of the questions that often seem to divide the country.

Accordingly, members of what we call the Melting Pot Moderates and Faithful Centre groups are much more likely to describe themselves as moderate than liberal, and are much more likely than the activist wing of the party to prefer a centrist Democratic candidate. The same is true of the Low-Key Pragmatists, who are also the most open to the idea of an independent presidential ticket led by a successful individual who is not a politician.

In other words, it’s easy to see how, in their fury with Trump, the Democrats could end up nominating someone who turns out to be his antithesis but not his nemesis.

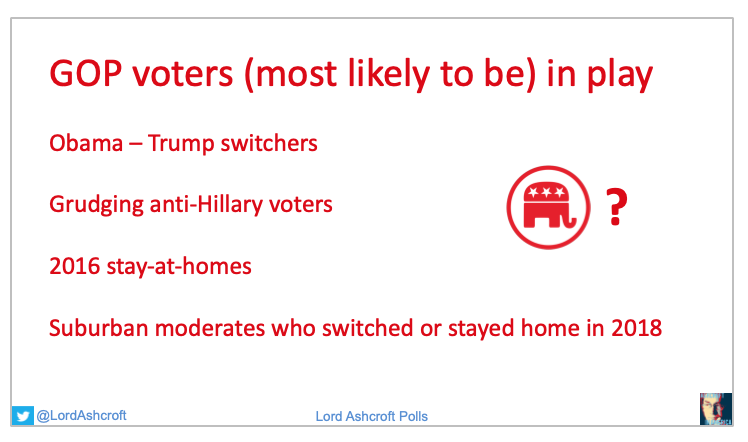

This is especially true when you consider the 2016 Trump voters who are most likely to be in play. These included switchers from Obama to Trump, thinking that he, not the Democrats, had their interests at heart. Also those who voted only grudgingly for Trump because they couldn’t bear the idea of President Hillary Clinton. Then there are those who turned out for their Republican Congressman but couldn’t bring themselves to vote for either candidate in 2016. And moderate suburban Republicans who are tiring of the President’s antics and have doubts about building a border wall, let alone shutting down the government over it, and who stayed at home or voted Democrat to make a point in the midterm elections.

All these people are theoretically open to an alternative and could be persuaded to take a serious look at all the options in 2020 – but are they going to line up behind a nominee that the most radical Democrats have chosen in their own image?

There is a long way to go, and we still don’t know how these things are going to play out. In our last round of focus groups we found Democrats already wrestling with the trade-off between choosing a candidate who can celebrate and a candidate who can win. Perhaps the progressive vote will be divided too many ways and a moderate will emerge through the throng. Perhaps the party will follow Labour and choose their own Jeremy Corbyn – in which case let’s not forget that in the general election Corbyn did rather better than anyone expected, probably including himself. Or maybe they really will follow the script that seems to be emerging and once again choose the candidate most likely to push ambivalent voters towards Donald Trump.

I will continue to watch with interest. Meanwhile, all the data I’ve talked about is available in more detail at LordAshcroftPolls.com…

…and did I mention that it’s also in my very reasonably-priced book. Order today while stocks last.

Thank you very much for listening.

Details of Half-Time! and the full data tables for the pot-midterm polling can be found here.