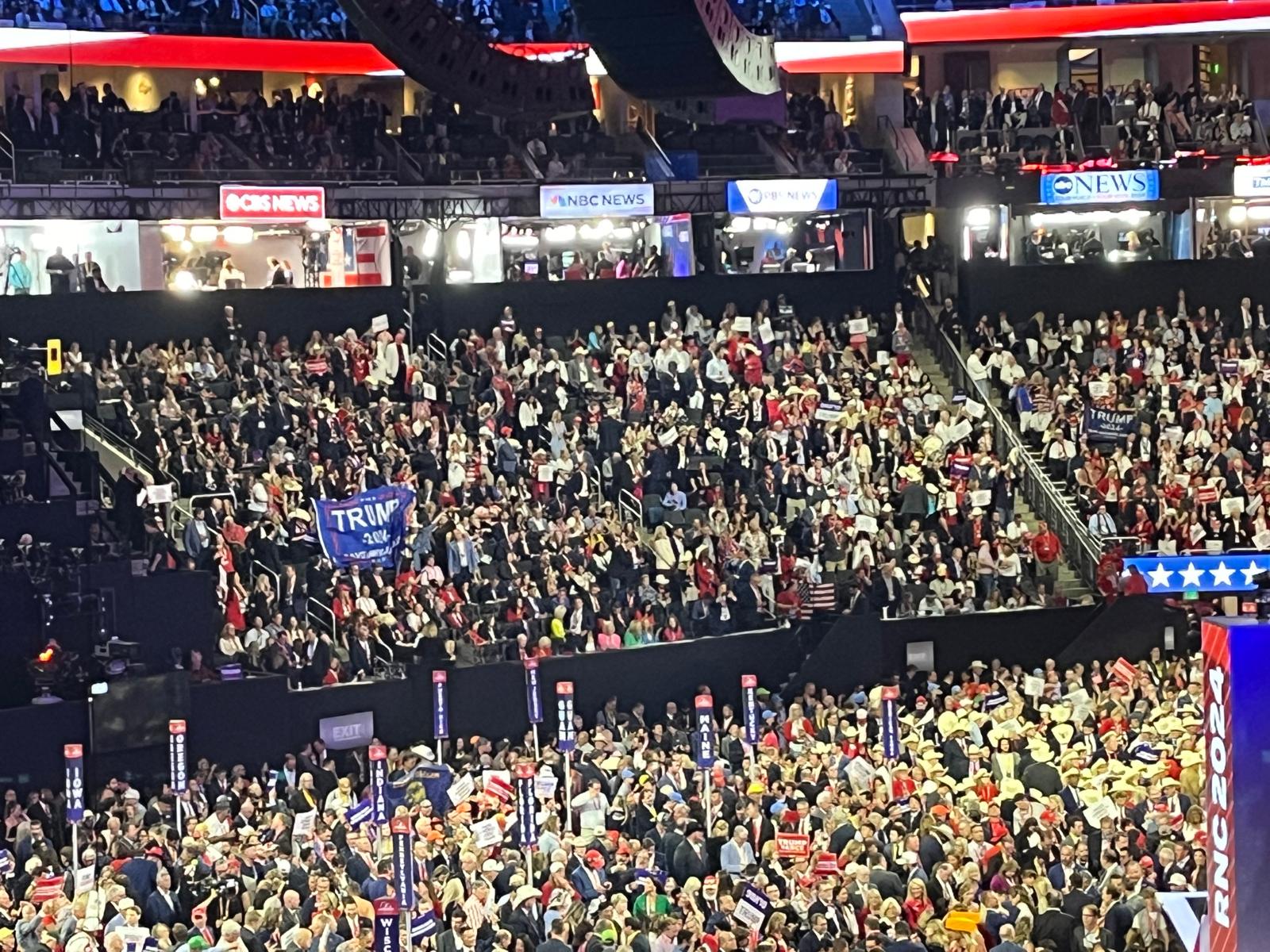

For many months before America’s midterm elections the conventional wisdom was that newly enthused Democrats, Republicans embarrassed by the antics of President Trump, and non-voters spurred into action by indignation at the state of their country’s leadership, would join forces to sweep the GOP from Capitol Hill.

As we know, this did not quite come to pass. While the Democrats gained 40 districts to take control of the House of Representatives, the Republicans strengthened their hold on the Senate, making a net gain of two seats in the upper chamber. Hardly the rout that Democrats had predicted – in fact, more like the tide flowing in both directions at once. What’s going on?

The straightforward answer is that the state-wide Senate elections included Trump-friendly small-town and rural voters, with the GOP gains being made in states it had carried in 2016. The competitive House races, meanwhile, were heavily concentrated in prosperous suburbs of big cities, where people take a more sceptical view of the President. My research during the campaign, which included focus groups in some of the key districts across the country, from New Hampshire to California, helped to illuminate some of the deeper dynamics of the race, and offered some signposts for what to look out for next.

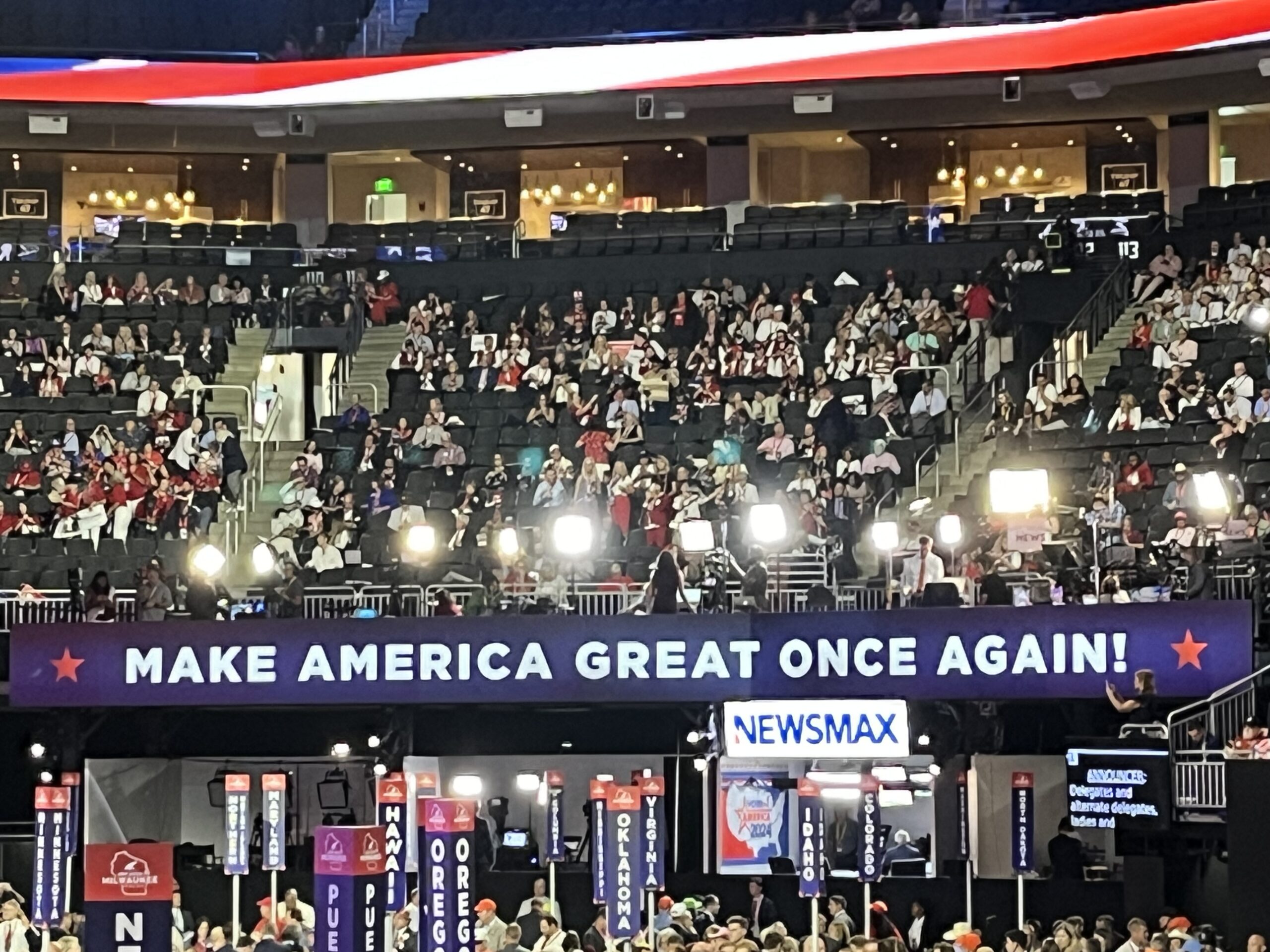

Much about current American politics is explained by that fact that while criticisms of Donald Trump focus largely on his personal behaviour, his supporters – including those who were initially reluctant – continue to separate this from his actions in office. Indeed, only one in three of those who voted for him mainly to stop Hillary Clinton say they approve of his character and personal conduct, but nearly nine in ten of them say they approve of what he is doing as President. This was confirmed throughout our midterm focus group research. As one woman in Iowa told us, “It’s like the CEO of the company I work for. I don’t care if you’re the nicest guy in the world. I care that we’re going to be successful and I’m going to have a job from day to day.” While critics are transfixed by his style, his electoral coalition is more interested in delivery.

As for what they think is being delivered, our Iowan’s example holds true. Again and again our groups mentioned the performance of the economy, which many attribute to a pro-growth, anti-regulation presidential agenda. This was a crucial point for many of those who had voted for him only reluctantly two years ago. “I thought he was a joke,” a man in California told us. “But being a blue-collar worker, being a construction worker, for commercial drivers the work has tripled for me since he’s been in office. So for me, OK maybe Trump is immature and he’s definitely not a politician, he’s a businessman. Maybe that’s what we needed.” My pre-midterm survey found that when asked about various aspects of his performance, both his stronger and more hesitant supporters, as well as independents and voters as a whole, award Trump the highest marks on the economy and jobs. His combative approach to ‘bringing back jobs’ to America, renegotiating NAFTA and confronting China over international trade, is an important part of his perceived record in this area – as well as being, in the eyes of his coalition, an example of what can be achieved with a more robust attitude to diplomacy than they believed America has adopted for some time. The President’s face-to-face meeting with Kim Jong-Un and the freeing of American prisoners from North Korea are regularly mentioned as further fruits of a tough and unapologetic stance.

Two other issues have had a particularly galvanising effect on the Trump coalition. The first is his nominations to the Supreme Court, a matter whose importance to conservatives cannot be overstated. We found during the presidential election that this was a decisive factor for Republican-leaning voters otherwise sceptical of Trump, and he has fully delivered on their expectation that he would appoint conservative justices. Brett Kavanaugh’s explosive confirmation hearings in the weeks leading up to the midterms helped propel GOP turnout by reminding Republicans of the battle they were in.

The second was border control, perfectly highlighted during the campaign by the migrant caravan wending its way to the American frontier from Honduras. Though Trump’s hard-line approach to immigration has appalled its opponents and made some otherwise supportive voters uneasy, for his own people it falls into the category of ‘promises delivered’, as it has since the so-called ‘Muslim ban’ in the very earliest weeks of his administration.

All of these things help explain why the Trump coalition has held together as well as it has in the face of the furious controversy surrounding every day of his presidency, and why the midterms did not produce the Republican wipe-out many had predicted. But there has been some erosion, as the House results showed, and we must remember that two years ago he lost the popular vote and won by only a tiny margin in some of the states that gave him the edge in the electoral college. The 2020 race, then, looks wide open and depends on two things outside the President’s direct control.

One of these is the economy. To the extent that his support rests on growth and jobs, greater confidence and higher living standards, it could be vulnerable should these things fade. The point was made succinctly by John Kasich when I interviewed him in the Ohio Governor’s Mansion shortly before the November election: “I know that one guy that I grew up with said the reason he likes Trump is because his 401k [retirement savings plan] is improved. Now I don’t know what happens after the stock market tumbles. Does that mean he doesn’t like him anymore?”

The other variable beyond his power to determine is how the Democrats decide to play things. They managed to turn out their supporters, engage previous non-voters (2018 turnout was higher than for any midterm election for more than a century) and persuade enough former Republicans to switch to capture key Congressional districts, but it is as easy to take the wrong lessons from victory as from defeat. The most misguided conclusion for them to draw would be that they are already on course for victory. The legendary Democratic campaigner Bob Shrum told me when I interviewed him in October that this danger was remote: “I don’t think after 2016 that there is the slightest chance that Democrats will ever again assume a presidential election is in the bag, at least those who were alive in 2016.” As one who had declared on TV “that no way no how, in no universe, not this one or an alternative one, could Donald Trump be President the United States, I don’t think people are ever going to get that complacent again.”

But as I found in my pre-midterm survey, few Democrats believe the party needs to rethink its ideas, and most think the key to victory is enthusing non-voters and their own base rather than reaching out to those who voted for Trump, however reluctantly. And as we found speaking to Democrats in the early primary states of Iowa and New Hampshire, many are torn between the need to reassure moderate independent voters and their own yearning for a more liberal, progressive candidate and platform which could frighten away some of those who helped put them in charge of the House. In 2020, the identity of President Trump’s opponent will matter as much as his record in office. The next chapter in America’s political story looks set to be as enthralling as the last.

This piece first appeared in the annual newsletter of the International Democrat Union.