This is the text of a presentation I gave yesterday at a meeting of the International Democrat Union in Munich, summarising my research on the US elections.

Good afternoon everyone. This event is very well timed, since the research I am about to share is described in more detail in my new book, which is out this week. It is available from Amazon or direct from Biteback Publishing. I am sure you will all take the chance to help a struggling author.

As you will know, my interest in polling goes back some twelve years, when I decided to look into the question of why the Conservative Party kept losing elections. Since that time, most of my research has been focused on British politics, but the contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton demanded a closer look.

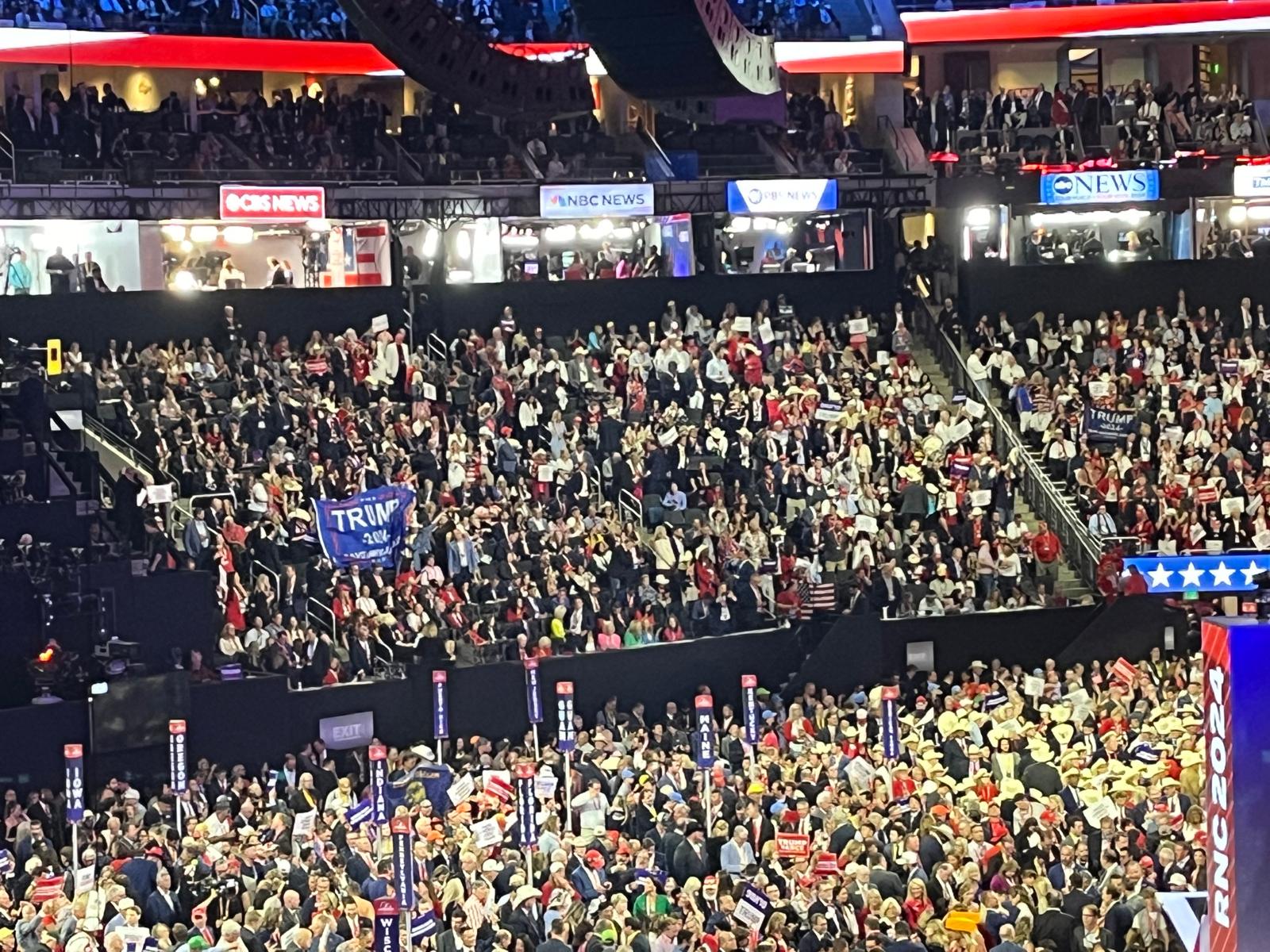

My Ashcroft In America project included 32 focus groups in the weeks leading up to the election in seven states: Wisconsin, North Carolina, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Florida and Ohio. On top of that, I conducted a poll of nearly 30,000 voters. I wrote up my observations of the groups every week on my website, as well as producing a weekly podcast featuring clips from the groups, as well as my interviews with figures including Mitt Romney, Reince Priebus and Howard Dean.

The idea was to look at the election from the voters’ point of view, to understand how they saw the choice and see what this told us about the state of American politics more widely. We were not doing “horse race” polling to try and predict the outcome. There were plenty of others doing that, and it is worth commenting briefly on what they had to say.

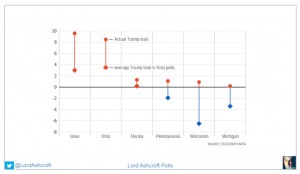

Nationally, the published polls didn’t do a bad job. The polling averages in the final week had Hillary Clinton about three points ahead – in the event, she won the popular vote by just over two points.

But in polls in individual swing states, particularly in the Midwest where the election was won and lost, there was a different story. The published polls had Hillary ahead in Pennsylvania and Michigan, and well ahead in Wisconsin. Though they had Trump ahead in Ohio and Iowa, they understated his margin of victory by an average of five and six points respectively.

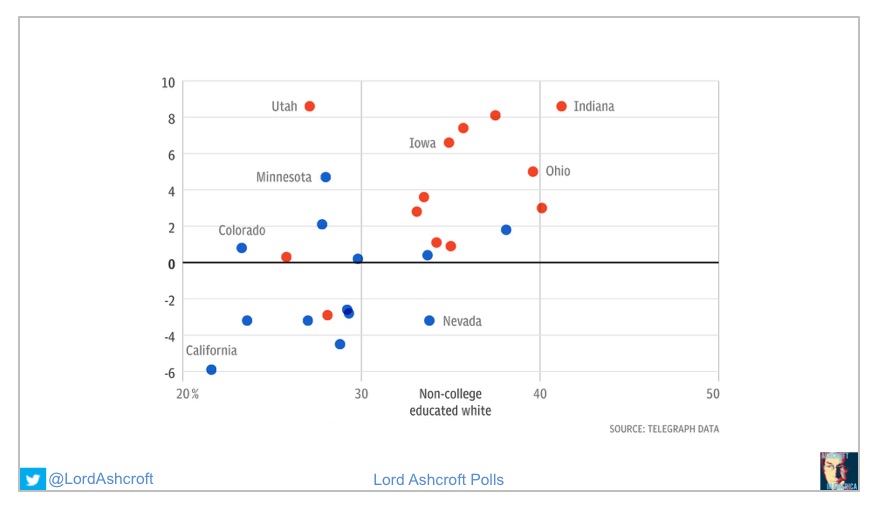

Individual state polls were not equally wrong, and the errors do not seem to have been random. The pattern that has emerged is that the higher the proportion of non-college-educated white voters in a state, the bigger the gap between Trump’s poll rating and his actual vote share.

As in the UK after the 2015 election, the industry will take some time to work out exactly why these errors came about – though it looks as though such voters were either not sufficiently represented in polling samples, or that their likelihood of actually turning out to vote was underestimated relative to that of other groups.

But whatever the explanation, I think a handful of imperfect polls in swing states is only one part of the reason why so many people found the election result such a shock.

As Sean Trende of Real Clear Politics has observed, the polls in battleground states in fact performed no better and no worse than they did in 2012, in terms of their average error. The difference is that while four years ago the polls understated the Democrat, this time they understated the Republican.

In other words, arguably, pundits ought to have been no more shocked by the result in this election than they were by the last one. The fact that so many of them were surprised is one of the obvious parallels between the presidential election and the UK’s Brexit referendum – a point I will come back to later on.

First, some thoughts on the contest itself: how voters saw the choice between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, and why Trump came out on top.

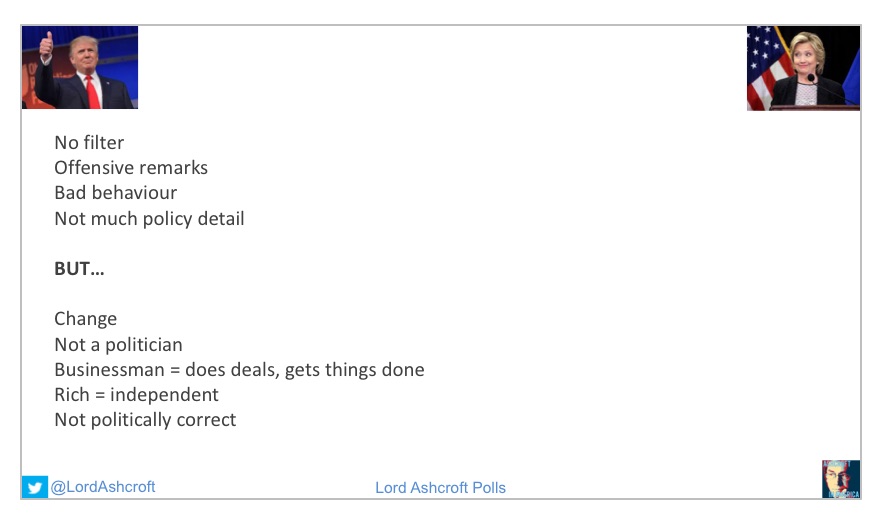

I think the first point to make here is that Americans who voted for Donald Trump did so with their eyes wide open. There is a view in some quarters that the only people who voted for Trump were lunatics or bigots, or that his supporters were somehow duped or misled. I don’t think that was the case at all. As in all elections everywhere, voters knew they were choosing between imperfect alternatives.

Donald Trump’s imperfections were clear, and those who were considering voting for him could see them. People worried about his temperament and said he had no “filter” – that he would say whatever came into his head and act however he wanted to. While this was sometimes entertaining, it also made people wonder what he might do when representing the US on the international stage. He was perhaps not ideally suited to diplomacy, and as one of our participants in Ohio put it, “do we want him smacking the Queen of England’s butt during a meeting?”

Trump’s remarks had sometimes gone beyond the unpredictable and into the offensive, especially when it came to his rhetoric on immigration or some of his thoughts on women. Indeed, when various women accused him of assault, many thought there was probably some truth in the claims.

As for his policies, these were rather hazy. Asked what he planned to do as president, people would cheerfully repeat “Make America Great Again”. But the only specific policy anyone in our focus groups could recall was building a wall on the Mexican border, but not even his strongest supporters actually expected it to happen – most thought it was a metaphor, or just a way of emphasizing that he planned to take a tougher line on illegal immigration.

Despite this, Donald Trump unarguably represented change. As all his flaws went to show, he was not a politician and did not try to behave like one. As a businessman, he had a reputation for doing deals and getting things done – in stark contrast to the political establishment that seemed incapable of changing anything for the better.

And being extremely rich – something that often counts against politicians on the centre-right – he was not beholden to any of the donors, lobbyists or vested interests who they believed held such sway over Washington.

If the details of his policies were obscure, there was no doubt that he represented a new direction because he shared people’s priorities. People in our focus groups worried about their job security, prospects for their children, the effects of immigration, the state of their infrastructure, and America’s place in the world – all things Donald Trump said he wanted to do something about.

And for people who felt their values were under attack, as many did, Trump’s refusal to be politically correct came as a breath of fresh air. He would halt the leftward, liberal drift in policy that they felt they had seen under President Obama – and which would continue under Hillary Clinton. And crucially for conservatives who were doubtful about Trump’s other qualifications, he would appoint the right judges to the Supreme Court.

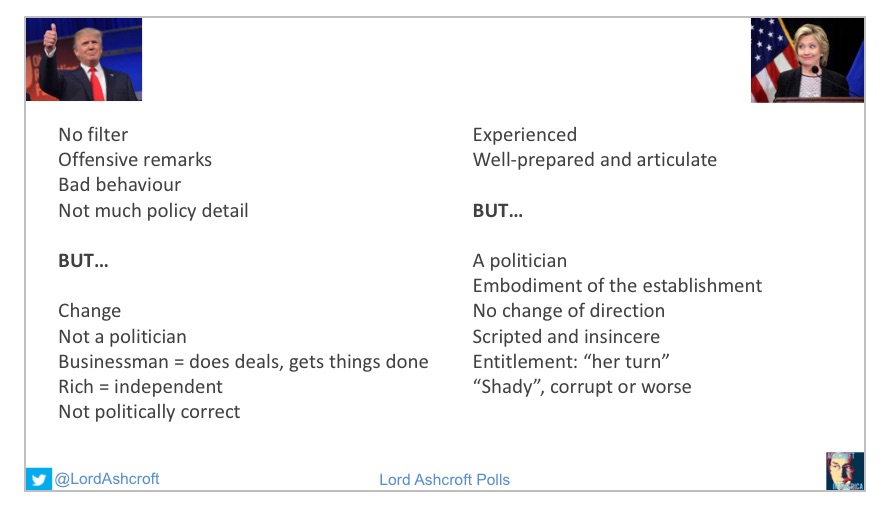

Hillary Clinton’s strengths as a candidate could have been designed to exploit Trump’s shortcomings. If he was temperamental, she was measured. If he was hazy on policy issues, she was always well-prepared, fluent and articulate. For some of the undecided voters we encountered, these things – combined with her experience, and the fact that she was not Donald Trump – were reason enough to vote for her.

But as with Trump, the downsides of Clinton were the flipside of her strengths. She was experienced because she was the ultimate Washington insider, the embodiment of the political establishment that so many people longed to be rid of. Her long experience also made it impossible for her to respond convincingly to voters’ demand for something new.

And if Clinton was measured, prepared, fluent and articulate, this also made her scripted and insincere. A politician, in other words. This is one reason why the televised debates, which were supposed to show why she was so much more qualified than her opponent, actually showed many people something else. As a man in Virginia told us after the first debate: “He’s up there showing who Trump is. She’s up there showing who that polished politician is, and then going behind the curtain and being her true self there.”

To many people, Clinton also exuded a sense of entitlement: as participants in our focus groups put it, she seemed to think it was “her turn” to be president. And her use of a private email server as Secretary of State was the most obvious example of someone who expected to be allowed to play by different rules from everyone else.

Moreover, there seemed to be something “shady” about her. She always seemed reluctant to be open about things until forced to do so – whether the reasons for her collapse at the 9/11 memorial, or the workings of the Clinton Foundation – and this fed the widespread idea that she was actually corrupt, or worse.

Ultimately, enough people in enough places decided that of the two, Donald Trump’s flaws were the more forgivable. His failings were personal, but provided he appointed good advisers and managed to control his temper, had little bearing on the way he ran the country.

Hillary Clinton’s failings were also personal, but with the important difference that they stood for things that affected the voters. Trump might be vulgar and have an unedifying attitude to women, but Clinton represented a Washington élite that lived by different rules, ignored the people it was supposed to represent and had no plans to improve their lives. That, it turns out, was the bigger disqualification from office.

One of the first things to strike us when we began our US research was a sense of déjà vu. Having spent months listening to British voters deliberate over the EU referendum, we found something eerily familiar in the way Americans talked about their own decision.

The parallels were not exact. Since American voters were choosing an individual, in some ways they had a better idea of what they were getting than their British counterparts: Donald Trump in the White House, the Oval Office, and the Situation Room. And while Trump would be president for four years with the option to renew, Brexit was for life (and beyond). But some similarities were evident. These are explored in more detail in my book, but very briefly, the main parallels I see are as follows:

First, voters on both sides of the Atlantic thought things were going in the wrong direction and wanted a change. Brexit meant change and so did Trump – but exactly what kind of change, no-one could be sure. People had to weigh the prospect of a new direction against the risk that came with it. Ultimately, enough people in enough places decided the risk was worth taking. As a man in Ohio put it the week before the election: “We know we’re not going to get any change with Hillary… A lot of people feel like, let’s roll the dice, and we’re going to have to put up with a whole bunch of bad stuff, but maybe we’ll get some things done with Trump.”

Second, many in the political and media world failed to understand that reasonable people might vote for Trump – just as they thought, five months earlier, that no sane or well-informed person could vote for Brexit. This was abundantly clear to people in Britain inclined to leave the EU, and made them all the more determined to vote as they wished. By the same token, Hillary Clinton’s description of Trump supporters as “a basket of deplorables” had the opposite of the intended effect – it simply created the “proud to be a deplorable” T-shirt industry.

Third, people’s decisions in both cases were closely related to how they thought they had fared from globalisation. In my referendum-day poll in Britain, Remainers were nearly twice as likely as Leavers to say they thought globalisation had been a force for good; in my US poll, Democrats and Republicans split in the same way. And just as reclaiming sovereignty was the biggest single reason Leave voters gave for their decision in the referendum, we found many American voters motivated by the idea of taking back control – that too much power was in the hands of financial institutions, multinational bodies, and domestic politicians who did not share their priorities or values.

Finally, I found in both cases that different sets of voters were divided not just by the immediate issues at hand, but on their wider outlook on life, and particularly their degree of optimism or pessimism.

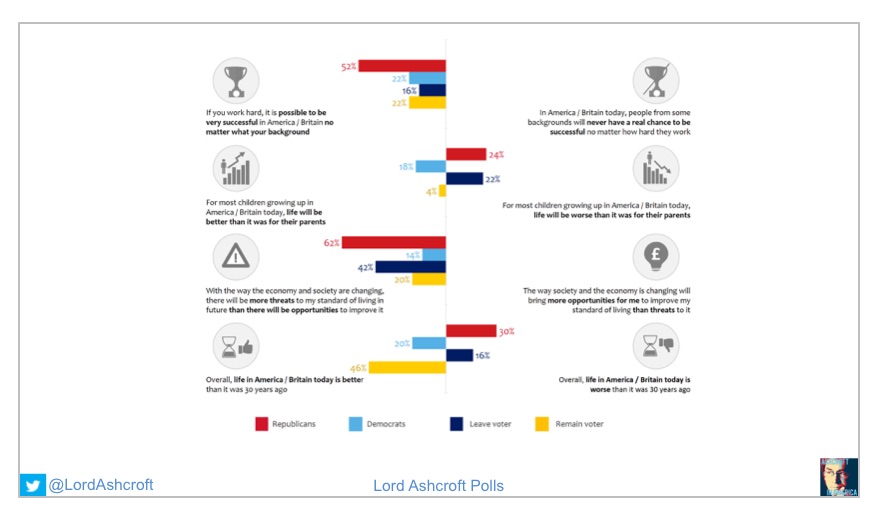

Democrats and Remainers thought, on balance, that for children growing up today in their respective countries life would be better than it had been for their parents; Republicans and Leavers thought the opposite.

Most people in all groups felt that changes in the economy and society would bring more threats to their standard of living than opportunities to improve it – but Leavers and Republicans thought so by much bigger majorities than Remainers and Democrats.

And while Remainers and Democrats thought that, overall, life was better in their respective countries than it was thirty years ago, Leavers and Republicans thought it was worse.

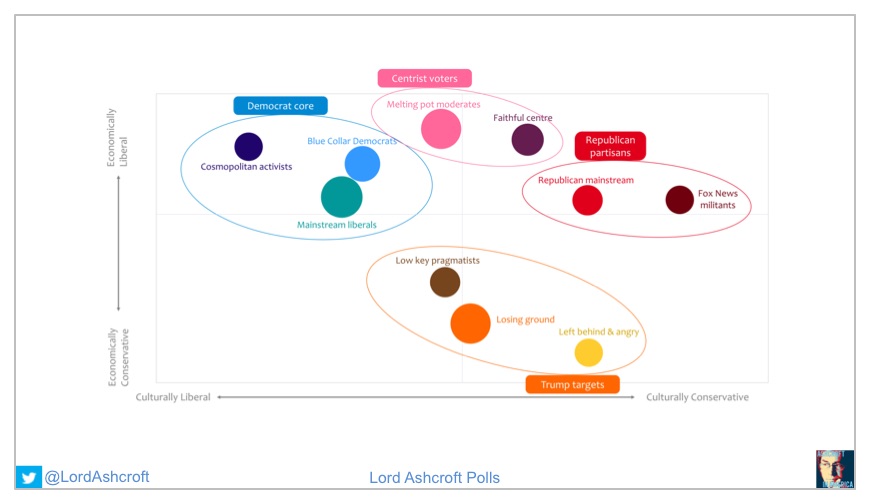

But as we all know, society does not divide neatly between supporters of different parties. My polling identified ten distinct segments of voters with different backgrounds, outlooks and priorities. The challenge for both parties is to maintain and expand a coalition of voters from this patchwork.

For example, our analysis found that the Republican base comprises two groups. The first we have called Republican Mainstream, who describe their views as moderate to conservative, and take what you might call an orthodox centre-right position on most things. Then we have what we describe as the Fox News Militants, who describe their views as very conservative and evangelical, and tend to think Hillary Clinton should be in jail.

Beyond the base, Donald Trump was able to attract voters who had been less politically engaged, with lower levels of education, and who were generally feeling left behind. While these groups were all part of the Republican voting coalition, that doesn’t mean they all want the same things.

For most voting groups, the biggest fear was being unable to pay for healthcare if a member of their family is seriously ill. But for the most committed parts of the GOP base, the biggest fear was “current immigration policies allowing terrorists into the United States”, followed by the prospect of “America becoming a socialist country like those in Europe”.

While the Republican Partisan segments strongly supported the idea of “smaller government offering fewer services” and that government benefits were too readily available, other parts of the party’s voting coalition disagreed – probably because they were more likely to rely on those services and benefits themselves.

And while the Republican Mainstream and Fox News Militants thought that “as the most powerful nation in the world, the US has an obligation to defend allies like NATO members, Israel and South Korea,” majorities in the Trump Target segments felt that the US “should only defend itself and has no obligation to protect other countries.”

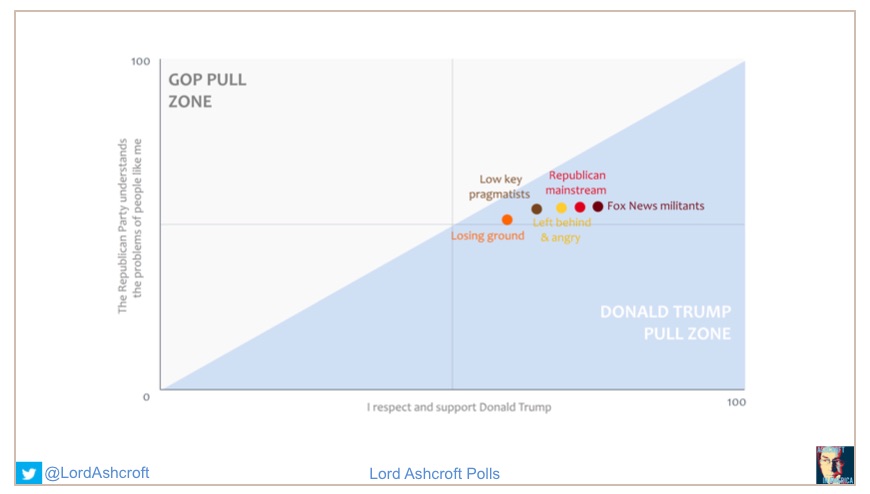

If we are likely to see tensions within the Republican voting coalition, we can also expect some battles between the White House and Capitol Hill. As far as the voters are concerned, they now have one-party government and so it has no excuse not to get things done. But in the event of disagreements, the evidence from my research is that Republican voters will be rooting for the President.

In our poll, we compared people’s levels of agreement with two separate statements: “The Republican Party understands the problems of people like me”, and “Donald Trump is a Republican who I respect and support.” In each of the Republican-leaning segments, Republican identifiers gave their level of support for Trump a higher score than their belief that the GOP is on their side.

Trump, in other words, was more of a pull for them than the party – an advantage we can expect him to exploit if he needs to. And as we found in our focus groups, even party supporters tended to see their leaders in Congress simply as part of the political establishment that needs to be shaken up.

This is the reason, by the way, why I would not expect supposed “scandals” like the Russian dossier – let alone the fuss over his refusal to answer a question from CNN at his press conference – to hurt him among his voters. He is their guy, and while they think he’s on their side they will stick with him.

To sum up, though this was in many ways the most extraordinary contest we can remember, the lesson it has for the rest of us is the same as always: that the voters are worth listening to, and they, not the politicians, will decide what an election is about. One way or another they will make themselves heard, and when they do, the result might surprise you.

Thank you very much.