A year after the coalition government was formed I embarked upon a research exercise which I called Project Blueprint. It looked at how the Conservatives could win an overall majority, and rested on the premise that if the party did not want to govern in coalition, it would need to build a coalition of voters big enough to allow it to rule on its own.

Just over a year since the 2015 election – and five years since the first instalment of Project Blueprint – the political landscape seems at first glance to be almost unrecognisably different. We have a new government led by a new Prime Minister, with no opposition in sight – whether from Labour, who are engaged in a bizarre drama of their own, from the Liberal Democrats, who have all but vanished, or from UKIP which, having accomplished its founding mission, will need to articulate a new purpose for itself. Oh yes, and the UK has voted to leave the EU.

But if the context is different, the Tories’ political mission is the same. Whatever the new administration may want to change from David Cameron’s time, there is one thing they need to keep: his electoral coalition. This may look today like a safe bet. But if there is one lesson from the last sixteen months – which have seen an unexpected Conservative majority, an unexpected new Labour leader, an unexpected Republican nominee for president, an unexpected vote for Brexit and an unexpected new PM – it is that nothing in politics can any longer be taken for granted, if it ever could.

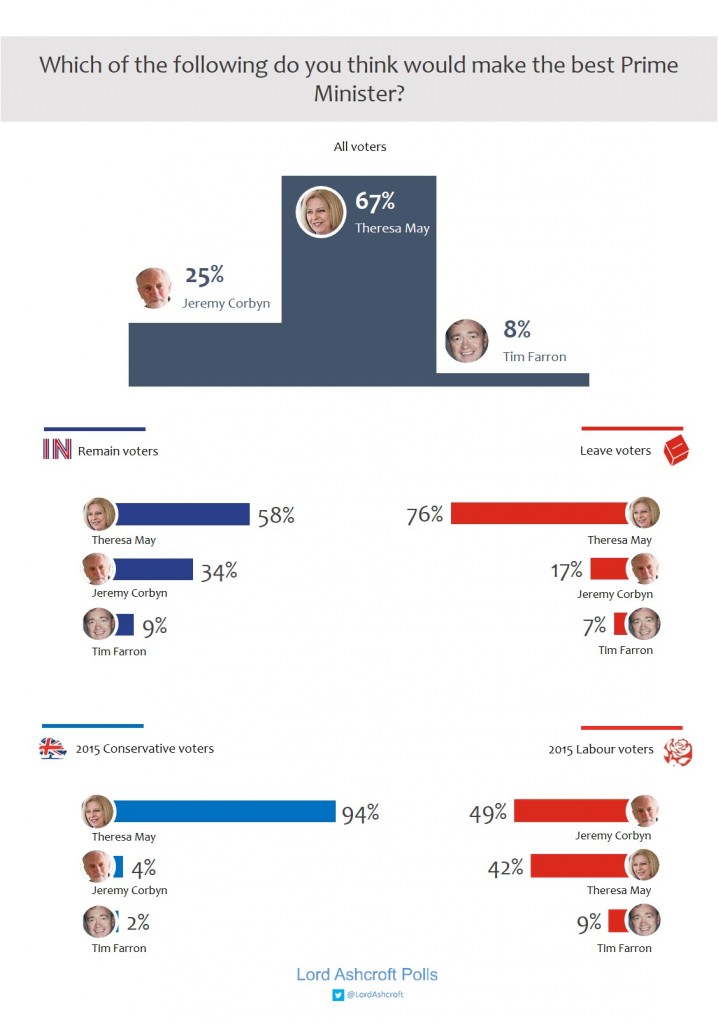

Still, the current signs could hardly be more encouraging for Theresa May and her team. Two thirds of voters see her as the best available Prime Minister. People in our focus groups spontaneously described her as capable, grounded, smart, tough, feisty, realistic, tenacious, statesmanlike, confident, sharp – and stylish. Some even said that when she took over they had sighed with relief to have a leader who was right for the times. Nearly three quarters including nearly half of those who voted Labour last year, said they trust May and Philip Hammond to manage the economy more than Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell.

The Tories were seen as the best party on the economy, negotiating Britain’s EU exit, cutting the deficit, dealing with crime, and reforming welfare, as well as being competent, willing to take tough decisions for the long term, and clear about what they stand for. Labour were still thought to be the most committed to fairness, and retained their traditional lead on the NHS (though no other policy area). But they were described by our focus group participants – including despairing Labour voters – as a shambles, a catastrophe, a basket case and a farce. The party had been taken over by “students, extremists, the far left”, and so had no prospect of returning to government. Mr Corbyn might be a decent enough person – though he had been damaged by the “traingate” controversy, which showed he was “just like other politicians” – but he was an activist rather than a leader. As one frustrated supporter put it, Labour have got to be “more than just a social movement – you’ve got to be able to get in and make the changes.”

Fortunately for Labour, there was very little appetite for a general election despite the change at the top – the general view was that everyone had had enough of politics for the time being.

Altogether pretty benign circumstances, then, for a new government. But lack of any effective opposition can make it harder to spot pitfalls, and this research gives some clues as to where to look for them.

The first is in tone. People in our groups noted with approval that there seemed a more formal, businesslike air to things, with less emphasis on PR than we had been used to in recent years. But they also often said there was something about Cameron that made them feel that they could relate to him, and which they felt must be reflected, in turn, in his political agenda. While people heard and welcomed Mrs May’s commitment to spreading opportunity to people from all backgrounds, many said they would wait to see whether this materialised in practice – and that they hoped her admirable drive and determination did not turn over time into stridency and refusal to listen.

The second potential pitfall is to do with priorities. Not surprisingly, when asked about the most important issues facing the country, negotiating Brexit on the right terms topped the list, with two thirds of voters naming it in their first three. But when it came to what concerned them and their families, it came fourth behind tackling the cost of living, improving the NHS and getting the economy growing. Securing Britain’s exit on the right terms will inevitably dominate the government’s agenda, but voters will not be impressed if it seems to do so at the expense of everything else.

The government’s third potential pitfall lies in the degree to which it succeeds in bringing the country back together after a bruising referendum debate and what was, for many people, a troubling result. The government is right to insist that Brexit means Brexit, and to act accordingly. But it should remember that many people are apprehensive about the future, including many whom the Tories need to keep in their coalition: “you lost, get over it” would not be a good message for them to hear from a party that will soon enough need their votes.

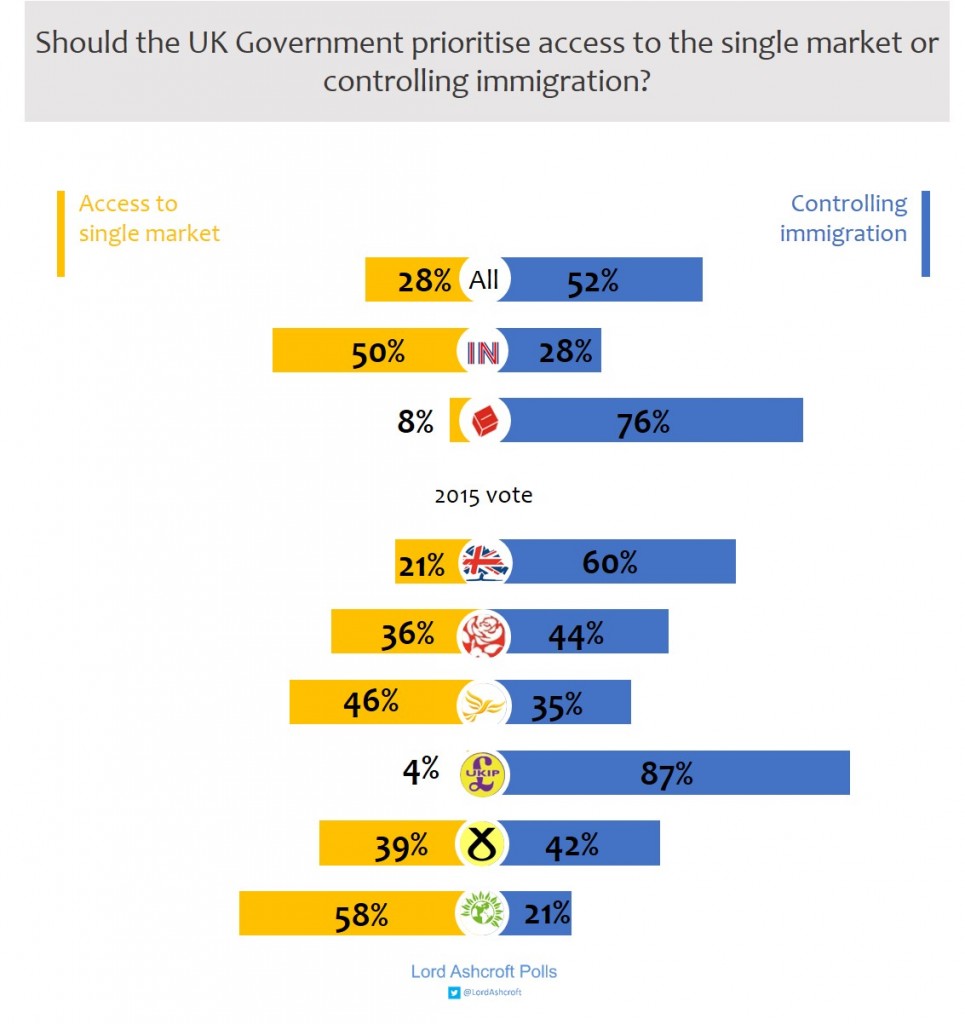

Achieving the right Brexit deal is the key. This would be a good deal easier if everyone agreed what the right deal looked like. The question of how to balance the aims of controlling immigration and securing access to the single market illustrates the point. Three quarters of those who voted to leave say immigration control should be the priority if it comes to a trade-off; those who voted to remain say it is more important to keep access to the market, by a 22-point margin.

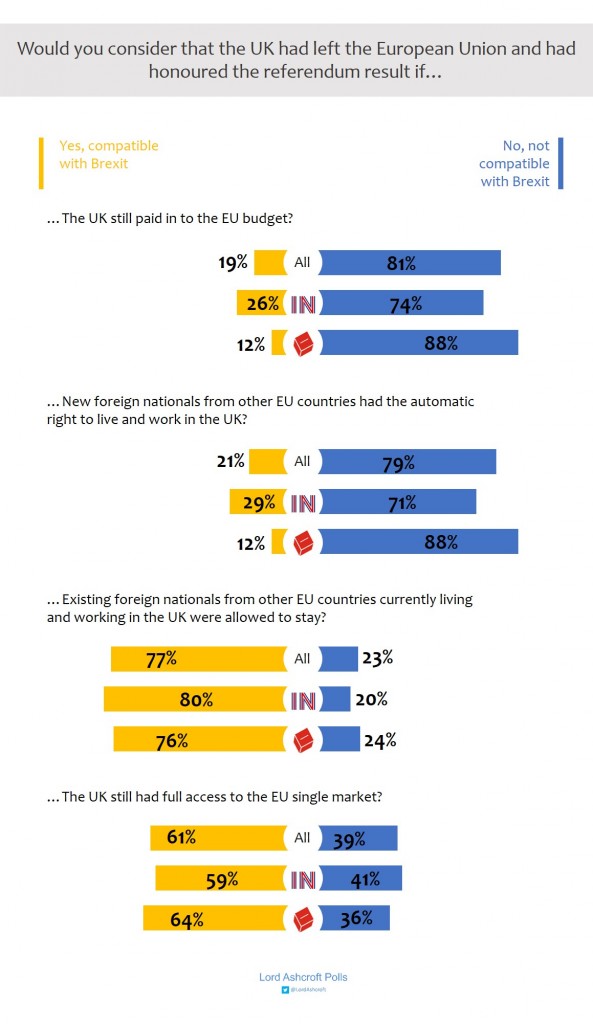

To add to the pressure, we found that many people simply don’t accept that any such trade-off exists. Even most remainers agree that new EU citizens having the automatic right to come to live and work in Britain would be incompatible with Brexit (as would continuing to pay into the EU budget). Unless the government can decide who can and cannot enter the UK, they feel, we would not really have left at all.

But whatever the technicalities of the single market, many are baffled as to why there should be any obstacles to carrying on trading as now, let alone why it should be the subject of tough negotiations. Since Europe benefits from free trade by selling more to us than we do to them, they ask, why in the world should we need to make concessions for it to continue?

The agenda is clear enough: immigration control, free trade, and reunite the country by proving you understand there is more to life than Brexit. No-one said government was easy.