This week’s focus groups with undecided referendum voters took place in Leamington and in Muswell Hill, North London, with only three weeks to go until the big day. “That will be the actual decision, will it?” It really will. “I don’t think it’s been highlighted that much, considering it’s such a big thing.” “In the paper I always see this ‘Bee-arr-exit’. What does it mean?”

Given the dearth of coverage, what arguments have people noticed from the Leave side? “The amount of money we pay into the EU. It’s a huge figure. If we leave we’ll be £30 billion or £300 billion better off.” “The big thing is probably immigration. We’d have more control of immigration into the country.” “Did George Osborne say it was £3,000 the average family would lose a year if we Brexit?” “There was something about people we have to keep in this country for human rights reasons because of the EU. We would have got rid of them because they were murdering or raping, or something, but we can’t because of, I don’t know, laws.”

And what have the Remain side been saying? “That if we leave, our house prices will drop.” “Gas and electricity prices will go up if we come out.” “Food will become more expensive”. “If we come out, it will have a big effect on employment because of exports and that sort of thing. The EU generates a lot of employment.” “I read the farmers would go bust.” Anything else? “I heard there was more likelihood of being at war if we left.”

*

Though the claims were accumulating, clarity was failing to emerge. “How do they know all this? They don’t.” “I don’t think the debate has developed at all, given the amount of time there’s been. There’s been nothing more of substance.” Though there were “a lot of facts and figures going round”, it was hard to tell what was right. “You see one argument and you think ‘that sounds good’, and then you see another argument and you think, ‘hold on’. It’s really difficult to make a choice.” Even those leaning one way or the other grumbled that they did not feel they had a proper grasp of the issues: “My frustration, as someone who is instinctively to leave, is the lack of clarity of the argument. There’s been so much time to put the two arguments to the public, and it’s such a critical and important vote in our lifetime, so I don’t understand why we failed to do that.”

Some felt wearied by the surfeit of democracy. “We get too many votes. The other day we had so many – police commissioners, local councillors. When you have to deal with daily life, it’s overwhelming.” “We should never have had a vote. It’s too complex. I just can’t understand the issue. With a referendum I think it needs to be something really quite simple, like in Ireland when they had gay marriage. You kind of believe in that one or you don’t.”

*

Given the complexity of the issues and the seeming impossibility of untangling the competing claims, “isn’t it down to who you trust at the end of the day?” Have any trustworthy characters yet come forth? “The Bank of England said something. They haven’t done too bad with getting us out of the recession, and they speak a lot of sense.” Mark Carney “seems like a nice man” and has the additional virtue of being “not a politician.”

Anybody else? “Lord Sugar, he’s a man who started with nothing, built up a business and he’s a millionaire now. He said to stay in. I think he’s man who would say it as it is. I would rather trust him than a politician.” “I looked at what Clarkson wanted to do, and he said stay in. I was gobsmacked. It’s the only thing that put me back on the fence.”

Who would you like to hear from who has yet to weigh in? “The Queen, but I don’t think she’s allowed to.” “Tony Benn. But he’s dead.” “Russell Brand. He wrote a book, didn’t he, about revolution.” “Yeah, but he told everyone to vote Labour. I thought he was credible until he did that.”

*

As it is, we are stuck mostly with the politicians and the politics, which is even more vexing than usual: “You’ve got traditional enemies joining forces against the others. That’s what makes it more complicated.” Some felt this was forcing them to think about the issues themselves (“I’m trying to get to the essence of it all”), which they regarded as healthy if tiresome. Still, the parties were inevitably part of the story.

On the Conservative side, the referendum debate was simply the latest chapter in the party’s ongoing Euro-feud: “It’s in the Tory DNA. It goes on all the time. In the Tory party it’s been forty years of two camps.” This time, it was also indivisible from “another element to this whole thing – whether Cameron is going to remain leader of the Conservatives.”

The suggestion that Cameron may have to resign if Britain votes to leave brought cheers in London, N10, but these were short-lived: “Then it will be George Osborne, and that’s even more worrying.” Though most thought it inevitable that the PM would step down if the referendum went against him, not everyone thought this was fair: “He shouldn’t be removed because of that. He has given people the democratic right to choose. I think it would be anti-democratic to remove him if the country voted for him last year.” Moreover, “I don’t like it when they swap leaders, like they did with Blair and Brown. The country should be able to vote.”

Even so, Cameron must be wondering whether had taken the wise course. “I think at first it was a good idea to give people a bit of a choice. But I think he’s sort of regretting it now.”

*

Some thought there might be truth in the suggestion from former adviser Steve Hilton that Cameron would probably be campaigning for Brexit were he not Prime Minister – not that this necessarily reflected badly on him or made any difference to their own position: “Relationships get formed, deals get done, handshakes are made and your position can change once you’re in the hotseat.”

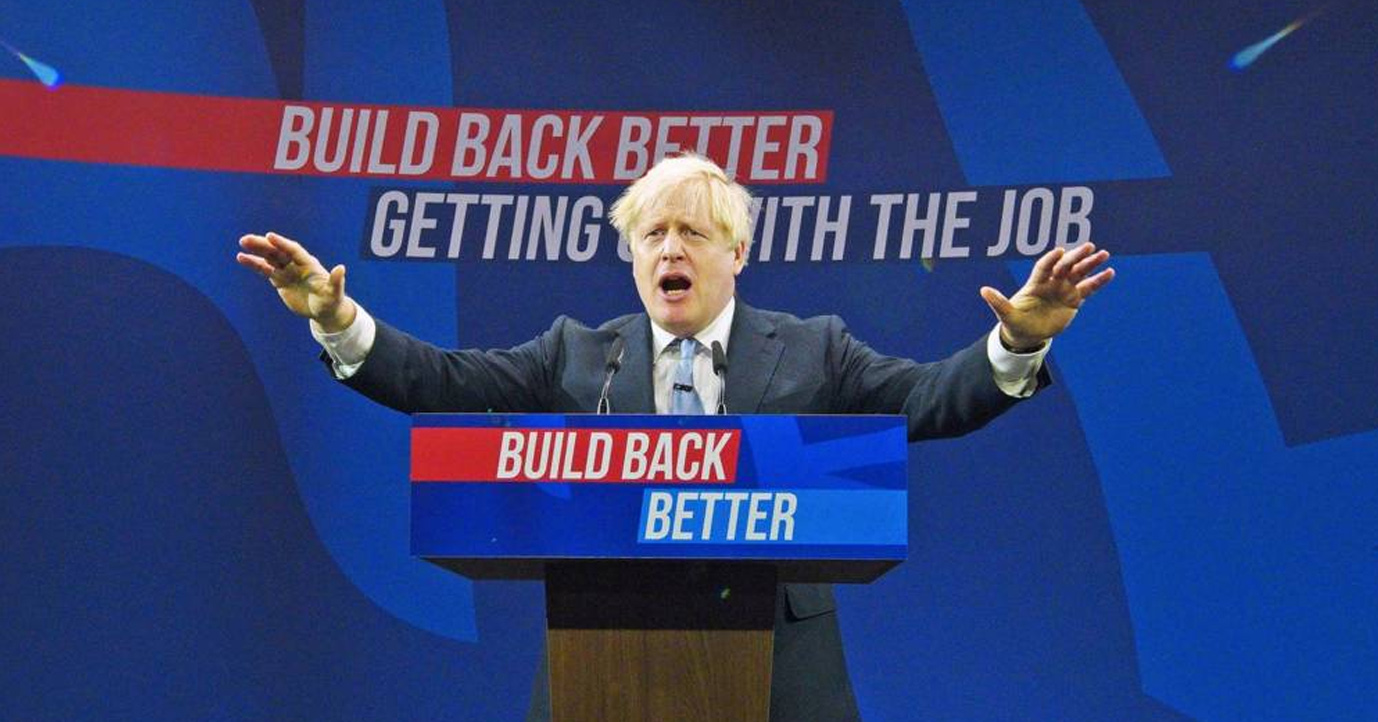

More to the point, if he had arrived at his position through expediency rather than principle, he would not be the only one: “Boris has got his eye on the top job, so he simply decided to go against it. He could easily be on the other side himself. It’s a pantomime;” “For me the whole thing with Boris is a bit iffy, isn’t it. The fact that he’s on the leave campaign, if Cameron loses this vote there is going to be pressure on him to stand down and Boris will take over and become the next PM. One has to be a little bit sceptical about Boris’s motivations.”

*

On the Labour side, the position remained opaque, though for different reasons. Jeremy Corbyn “finally came out and said something today. Although it was a very veiled message, because he said some very pro-Brexit things as well.” “This was today? Why is it so late? I thought he would have said it a bit sooner.”

Corbyn’s argument sounded equivocal to a few (“I think he said on balance we should stay in. ‘On balance,’ that’s not a very strong argument”), but for others it reflected a more realistic approach to the hysterical certainties emanating from either side: “It’s just close to the way I think. I just don’t really know, and on balance I can probably pick some things that make the most sense to me.”

*

Participants had noticed the Prime Minister campaigning alongside the new Mayor of London earlier in the week (though showing the groups a picture of the event proved the latter’s fame still had further to spread: “Who is that with David Cameron? Is it some businessman?” It’s Sadiq Khan. “Oh yeah, that’s right. What business does he run again?”) Though some had been encouraged by the cross-party moment, the spectacle had not appealed to everybody: “When I saw this I completely tuned out because I couldn’t get over how set up and staged the whole thing was. I don’t know if it’s just David Cameron but I just can’t take the whole thing seriously. I don’t feel any honesty coming through.”

However authentic or otherwise they found this display of unity, people were puzzled by Jeremy Corbyn’s apparent objection in principle to campaigning with Tories, given the other company he had kept: “It’s interesting that the Labour leadership are annoyed about it – you can share a platform with Hamas but not Cameron!”

*

The TUC’s calculation that Brexit would leave the average worker £38 a week worse off was treated much the same as similar interventions from other bodies: “Where have they got that from? Have they just made it up?” “Figures can be squiffed, can’t they?” “Everyone’s got an agenda.” Even if there were some truth to the claim, a few thought the figure sounded trifling compared to the bigger questions at stake: “We want our country back, don’t we?”

The more worrying part of the unions’ message was the potential erosion of employment rights. “One thing I really like about Europe is protection of the worker… I’m just worried that they’ll squeeze the workers if we fell into a recession. Workers do need protection. There are a lot of low-paid jobs out there.” Without the EU to enforce these rights they could start to disappear “slowly but surely, maybe one right at a time, so to speak… We could be following in American footsteps.” But nobody thought employment law would be repealed straight away: “Surely if all these rights have been instigated you can’t just turn around and take them away. The unions would have something to say about that.”

*

Participants had noticed the Leave campaign’s proposal for a new points-based immigration system, and the open letter to Cameron from Boris Johnson and Michael Gove (though this was seen mostly in terms of Tory leadership manoeuvres). Immigration was a very big issue for many in the groups, and the renegotiation earlier in the year had not solved the problem (“Cameron says they can’t come here and claim our benefits, but they do!”).

Even so, there was a very mixed reception for Priti Patel’s argument that Cameron and Osborne fail to understand people’s concerns about immigration numbers because of their wealth. Some agreed (“He doesn’t work in the hospitals, hasn’t been in Warwick Hospital like I have today, absolutely run ragged. He doesn’t see the effects it’s having on real people”), but at least as many thought this was unfair, or at least that it applied no more to them than to other politicians (“I think they’re just picking on Cameron. You can say that about any politician, can’t you. Had a private education, had a lot of money…”; “She’s probably quite rich too.”)

The idea of a proposed immigration policy was popular (indeed, “an Australian-style-points-system” is eventually demanded in nearly all focus groups, whatever the subject initially under discussion). The principle seemed unarguable to many: “It would be our choice. We could calibrate it according to the country’s needs.”

More doubtful, though, was the idea that the number of people entering Britain would fall if we left the EU, let alone the number of people already here. One reason was that people often made no distinction between the refugee crisis and free movement of workers, and some worried that we would lose French cooperation at Calais in the event of Brexit: “Even if we left the EU we would still be getting immigrants, but in a more dangerous way… At the moment we have France protecting our borders. As soon as we leave Europe, there’s a concern that that will stop and we could get a flood of migrants coming through.” Moreover, “the refugees and illegal immigrants are the ones that are putting the strain on, not actually the ones from the EU.” And surely free movement of people was a central part of the single market: “If we want a trade deal with the EU after we leave, that’s one of the conditions they’ll make us do.”

If the EU were to leave and new arrivals did fall dramatically, the pressures from previous immigration would still exist: “Even if we were out, the housing is already gone. A Tory won’t do anything about that.”