For this week’s focus groups with undecided referendum voters Lord Ashcroft Polls visited Birmingham and, for a Scottish perspective, Glasgow. Here, the decision at hand seemed to most participants at least as important (but much, much less interesting) as the independence referendum nearly two years ago.

This was partly because the European issue was less emotive than Scottish independence: “It’s a bit anticlimactic in comparison. People were more passionate about the change in the Scottish referendum than they seem to be about the change if we leave the EU. This is a damp squib.” The 2014 vote really had led to new levels of civic engagement (“People on Facebook who used to put up videos of themselves lighting their farts are now talking about politics”), but while “everyone and their dug” had been talking about independence, the EU debate had not really taken off.

One reason was that the Holyrood elections meant the Leave and Remain campaigns had yet to get into full swing. The government leaflet was only now being delivered, though some had received the guide from the Electoral Commission (“Oh is that what it is? I thought it was from Virgin Media”). After the saturation campaigning they enjoyed or endured last time round, many felt rather lost: “Scottish independence was more in-your-face. You couldn’t get away from it. That has made me lazier. There were debates, it was on all the time. Now people ask me what I think and I don’t know because I haven’t been force-fed.”

As a result, many felt unsure what was at stake: “People don’t truly know what they’re being asked as they did in the Scottish referendum;” “I knew what I was doing then, I knew where I was going. But with the EU, I just don’t have the information.” Worse, after the protracted independence campaign, they only had five weeks left to make their minds up: “We’re being told by both sides that it’s a fundamentally important decision, but we’re being rushed into it.”

*

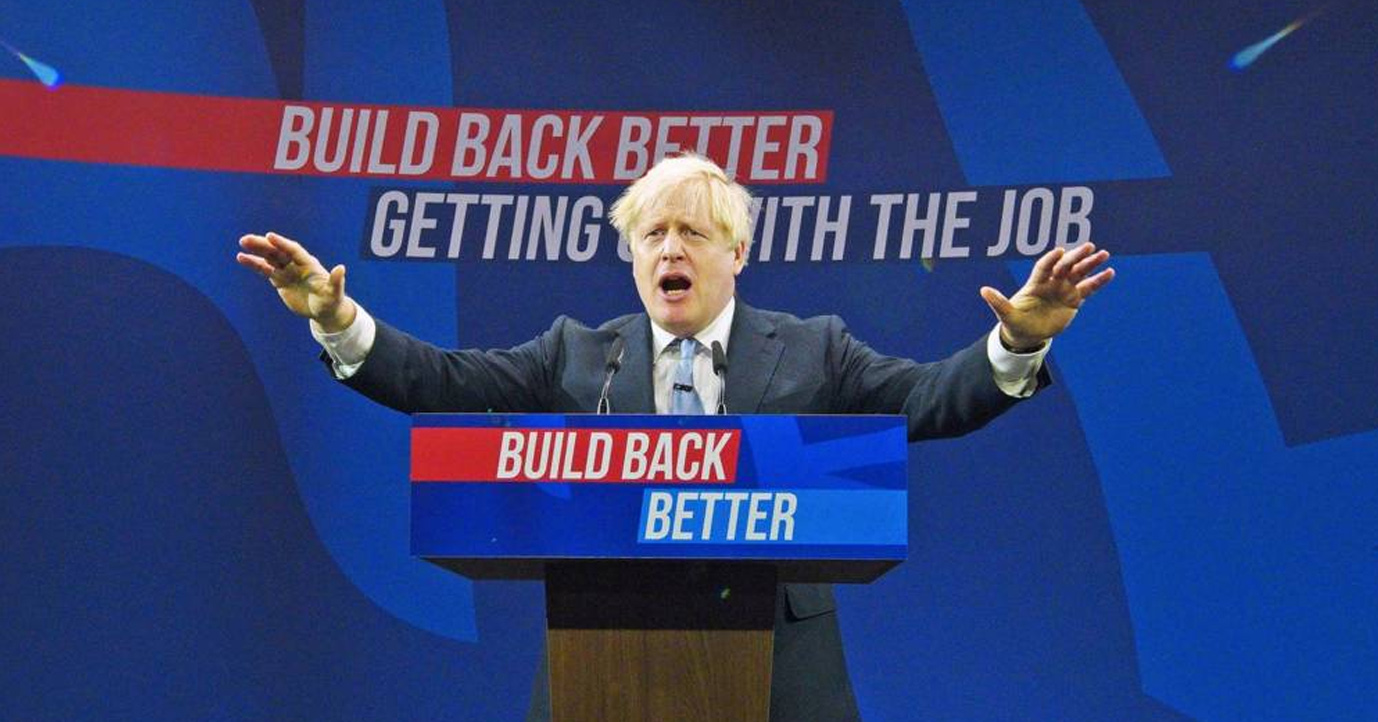

For some in Scotland, another reason not to be enthused was that it seemed like a row between English people, and – worse – English people of a particular type: “I see it more as a leadership contest in the Tory party. When I see a choice that involved David Cameron, Bojo and Nigel Farage, I think ‘that’s a choice that doesn’t involve me’;” “It feels like an English thing. They’re preoccupied with the whole Europe question but it doesn’t really bother me. Rule Britannia, Nigel Farage, Boris – Scotland seems to be put to one side;” “Not a lot is broadcast from a Scottish point of view. It’s all coming from down south.” The lack of good information or any strong lead from others (“Jeremy Corbyn is voting to stay but he doesn’t agree with it… He argued for thirty years that we should leave”) meant people were having to “rely on folks like Farage and Boris Johnson that we would otherwise discard like an old jumper.”

*

One figure who seemed notably absent from the debate so far was Nicola Sturgeon. Most knew the SNP supported Remain and the rest assumed it did, but none could recall hearing the First Minister explain why. What they did think they had clocked, however, was that she seemed to see the EU debate first and foremost as a route to re-opening the question of independence: “She’s not saying ‘this is why we should stay’. She’s obviously hoping Scotland vote yes and England vote no so she has an excuse for another referendum.”

So far people were prepared to give her the benefit of the doubt (“She’s been focused on Holyrood. You can only fight one fight at a time”) but now they wanted to hear more from her on Europe itself: “She’s the leader of this country so her opinion and views should really count for something.”

*

On the subject of neverendums, there was no enthusiasm in our groups for Nigel Farage’s suggestion that a narrow victory for Remain would lead to unstoppable demand for a second vote. “Scotland was supposed to be once in a generation, so we’ve got to stick to that. It should be the same with this… When it’s done it’s done;” “Would we keep going round in circles every five years?” People in both locations felt a decisive result would be better than a narrow one, and feared the question would stay on the agenda if it was very close. But nobody wanted the campaign repeated, particularly since many could barely summon the will to focus on this one (“I don’t want to do it again!”).

*

Now for what is becoming a regular feature of the focus group tour: why has Boris has been in hot water this week? Some of the participants knew Hitler had come into it somewhere, though some were not sure how (“he didn’t do one of those salutes, did he?”) and a few who had heard what he had said thought it had been in poor taste: “He’s talking about people who wanted to rule the world and send people to gas chambers.” But not for the first time, after hearing what he said in his Telegraph interview, most thought the fuss was out of all proportion to his remarks (“bampot” though he may be). The argument that the EU was trying to unite Europe by other means where various figures in history had failed to do so by force was quite a persuasive point for some (“it would make me think again”; “Hitler wanted to rule Europe and so does Angela Merkel and Luxembourg”) and certainly a valid one to make: “He was alluding to the fact that people have tried to amalgamate Europe many times, and this is another version of it.” As for the row, “seriously, Hitler was someone in history and we shouldn’t pussyfoot about it.”

Had he made the same point without using the H-word the rumpus would have been avoided, but most did not think this was a misjudgement on Boris’s part – quite the opposite: “I think he knew what he was doing.” In their view, the same applied to David Cameron’s speech last week. If what he actually said about security led the papers to exaggerate and talk about war, that was just fine: “They’d rather get the front page. They were both happy.”

*

Most in the groups had heard about the latest intervention from the IMF. They watched a clip of Christine Lagarde giving her view that the potential consequences of Brexit ranged from “pretty bad to very, very bad”, but were not won over. “Is she German?” No. “Belgian?” No, she’s from France. “I knew it was one of the Europeans. She’s more concerned about what’s going to happen to the rest of them.” Some thought an international body would by its very nature favour existing structures (“the fact that it’s the International Monetary Fund speaks volumes”) and would be terrified of what could follow a vote to leave: “A lot of them have vested interests, especially the rest of Europe. They are having trouble with Greece, Cyprus, Portugal – if Britain leaves they’ll turn around and say, well, we’ll leave too.”

Besides, “historically the IMF have got a lot of things wrong, so I’m not convinced. The idea that we’re going to end up on our own doing nothing is nonsense.” Most felt trade was one of the strongest reasons to remain, but some did not worry about isolation: “No-one bloody likes America and they manage to trade. I don’t see why we would have so many problems.”

*

Mixed views this week about the Governor of the Bank of England. A few in Scotland remembered him as “the one who said we couldn’t have the pound”, and some saw him as a banker and therefore not to be trusted (“does he get a banker’s bonus?”) On the other hand, being from Canada he had probably not been a member of the Bullingdon Club.

For some, his warning about the risks of leaving was “scaremongering”, to which the Scots in particular felt they had become expertly attuned (“I think the over-electioned Scottish electorate won’t fall for it in the same way as the rest of the UK”). The groups thought both sides were guilty of making laughably overblown claims; one drew an analogy with the millennium bug: “I feel it’s like when the year 2000 came and everyone thought the computers would crash and it would be terrible. We woke up the next day and nothing had happened.”

However, some were beginning to put any warnings about what might happen if we stayed or left – however mild and well-reasoned – into the scaremongering category. Others were frustrated by this, seeing it as laziness and an excuse not to engage (“you can’t just dismiss people. He knows what he is talking about… You say the word ‘scaremongering’ but there must be some truth in it.”)

Though people would often dismiss individual interventions, particularly on the remain side – it was none of President Obama’s business; companies looked after their own interests, not Britain’s; the IMF had been wrong before – some admitted there was a cumulative effect, at least in sowing doubt. “That’s what they’re trying to do.”

*

The sight of George Osborne, Ed Balls and Vince Cable speaking together in front of a Ryanair plane also carried echoes for people of the final stages of the Scottish referendum, even if they could not put a name to each face. “Who’s the one on the left? Is it Ming Campbell?” “The middle one is in charge of the money, the one who brung in the bedroom tax.” “The Three Amigos.” “The Three Stooges, more like.”

For some, the cross-party nature of the campaign carried some force: “I’m not a great fan of Cameron, but he’s quite a good speaker, and he and Nicola Sturgeon and Jeremy Corbyn are singing from the same hymn sheet.” But in an echo of the earlier complaint from Scotland, the Birmingham groups felt “those types of people are all a bit samey… I think of the politics of London, they all went to the same school.” As we have seen before, this – and the fact that the Tories were so divided – made things even more confusing: “Usually I’d say ‘what do the Tories want?’ and do the opposite, but you can’t even do that.”

The image caused some to reflect on the nature of sovereignty. “Do you mean these people having control, the people we have just laughed at? That makes me worry.” Then again, “If we’re going to balls our country up let’s do it ourselves, not let somebody else do it.”