My latest five-thousand sample survey shows how the referendum campaign is developing, and sheds light on the competing themes of the two campaigns: Remain’s emphasis on the risks of Brexit, and Leave’s mantra ‘Vote Leave, Take Control’. Here is what we found:

1: Opinion remains divided, but the Leave vote is hardening

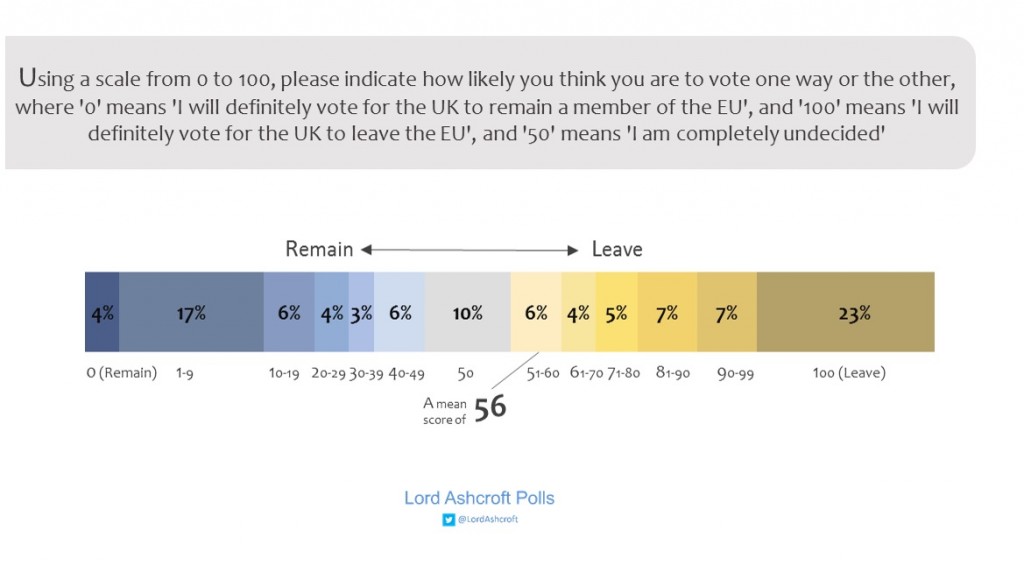

I asked respondents to place themselves on a sentiment scale, where zero meant they would definitely vote for Britain to remain in the EU, and one hundred meant they would definitely vote to leave. A score of fifty meant they were completely undecided; another number meant they were leaning slightly or strongly one way or the other. (This indication of sentiment should not be compared directly with standard voting intention polls which replicate the referendum question).

Several points emerge when comparing these numbers with the findings when I conducted the same exercise last December. Overall, opinion has remained broadly stable: the proportion putting themselves on the Remain side has risen two points, the proportion on the Leave side by five, and the number at exactly fifty is down. However, the shift in the mean score from 51.9 to 56 owes more to the growing concentration of the Leave vote at the far end of the scale. Nearly half (44%) of those placing themselves in the Leave half now give themselves a score of one hundred, meaning they are certain to vote that way, compared to just over one third (34%) five months ago.

As the other results show, with a month to go until the referendum, these numbers are by no means set in stone.

2: The ‘control’ argument is potent…

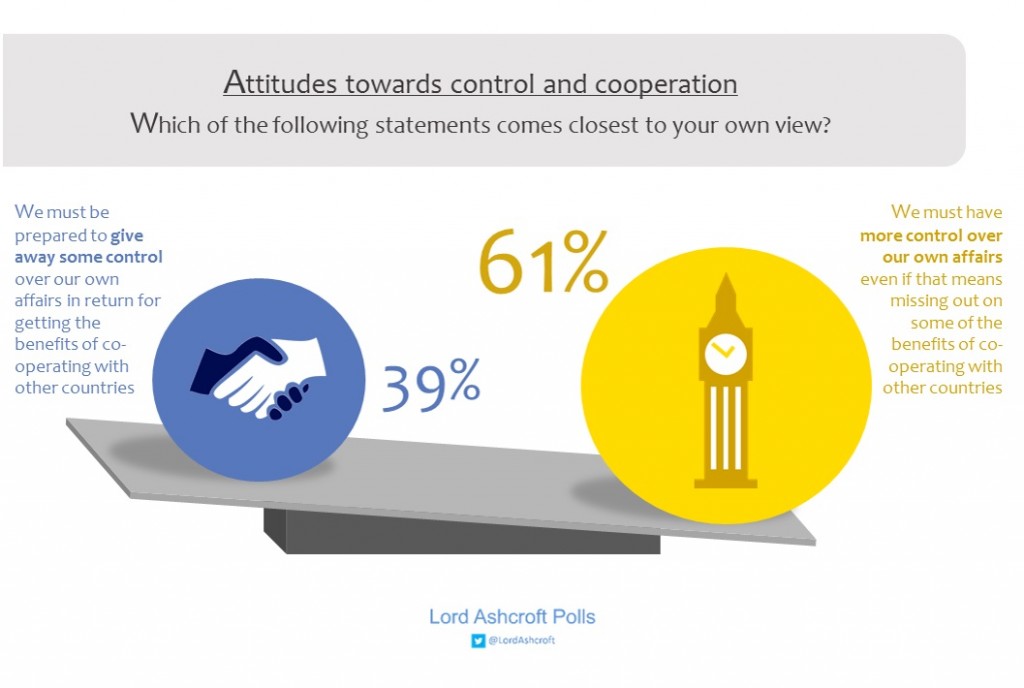

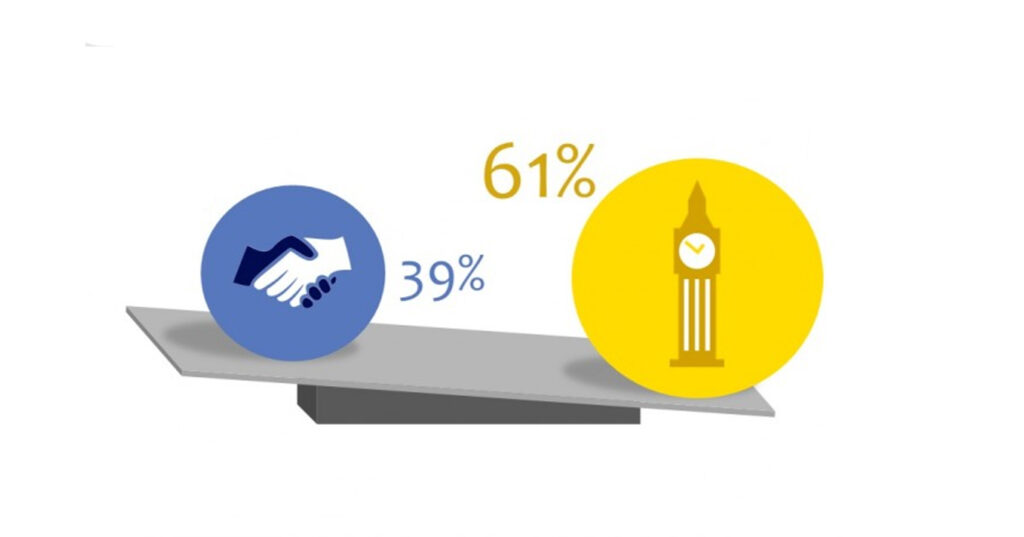

Sir John Major recently argued that total sovereignty is an illusion in the interconnected world of today. Most people in our poll felt that too much control had been lost and needed to be regained.

Just over six in ten thought “we must have more control over our own affairs even if that means missing out on some of the benefits of co-operating with other countries”. Seven in ten 2015 Conservative voters agreed with this, as did 85% of those on the Leave side of the scale and 94% of UKIP voters. Most Lib Dem voters and 18-24 year-olds, by contrast, thought “we must be prepared to give away some control over our own affairs in return for getting the benefits of co-operating with other countries. SNP voters (perhaps conscious of a potential contradiction with other parts of their political outlook) were evenly divided, as were Labour voters.

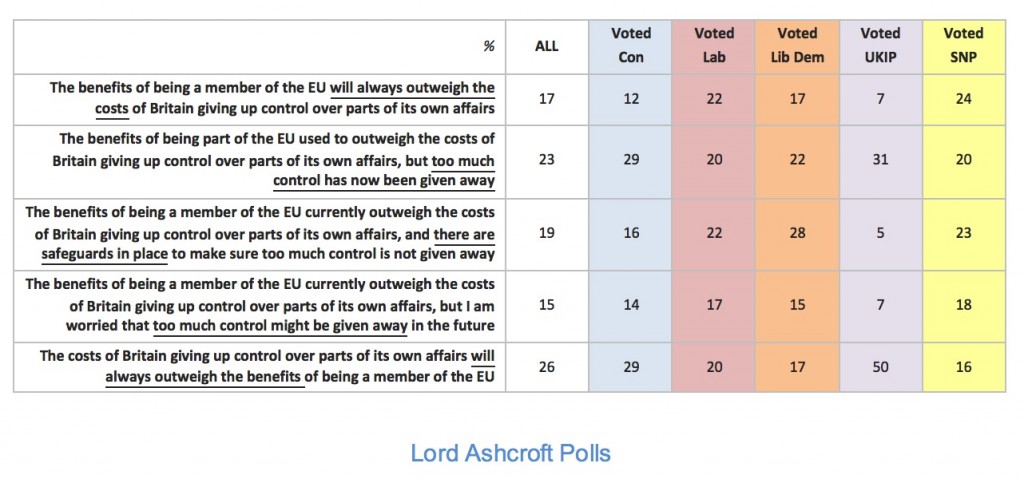

We looked further into this question by asking whether this was a matter of principle, or whether a boundary had been crossed (or was approaching).

Just over one third (36%) said either than the benefits of EU membership would always outweigh the cost in terms of giving up some control over our own affairs (17%) or that the benefits currently outweighed this cost and safeguards were in place to ensure too much control was not given away (19%); nearly two thirds (63%) of those on the Remain half of the scale chose one of these options.

The rest said the benefits used to outweigh the loss of control but too much control had now been given away (23%), were worried that too much control might be given away in the future (15%), or thought the cost to Britain of giving up control over parts of its own affairs would always outweigh the benefits of being an EU member.

On the specific issue of immigration, which is the area in which people most often feel control has been lost, a higher proportion than in December thought that “we’ll never be able to bring immigration under control unless we leave the EU” (46%, up from 39%). Nearly six in ten (59%) of those on the Remain side of the scale thought “we won’t be able to bring immigration under control even if we leave the EU.” Overall, 34% chose this statement, down from 37% five months ago.

3: …but ‘risk’ looks equally powerful

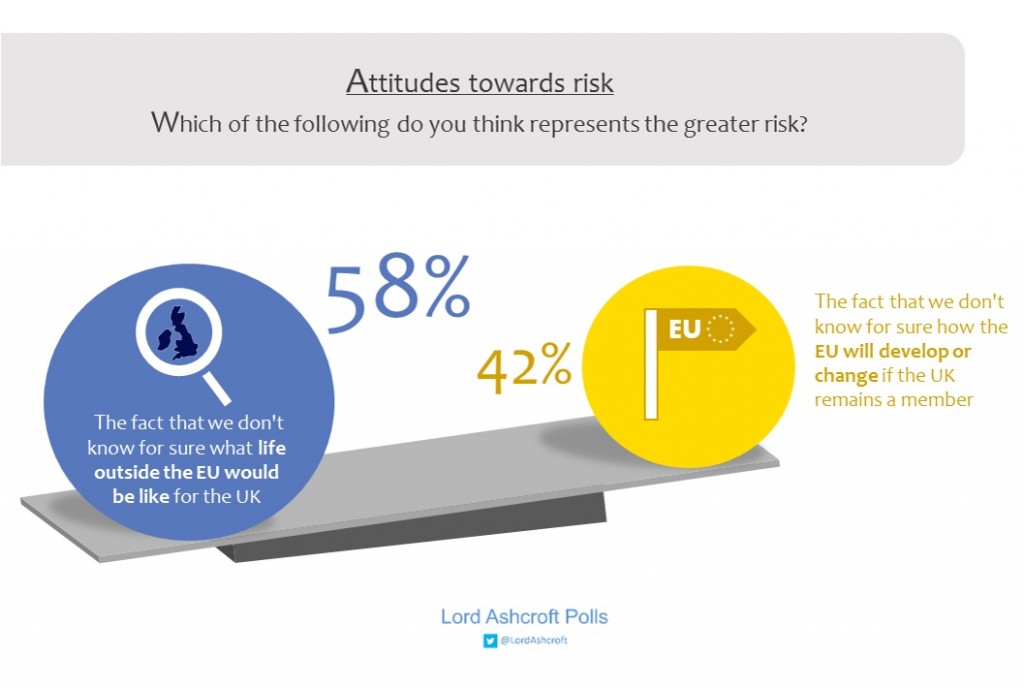

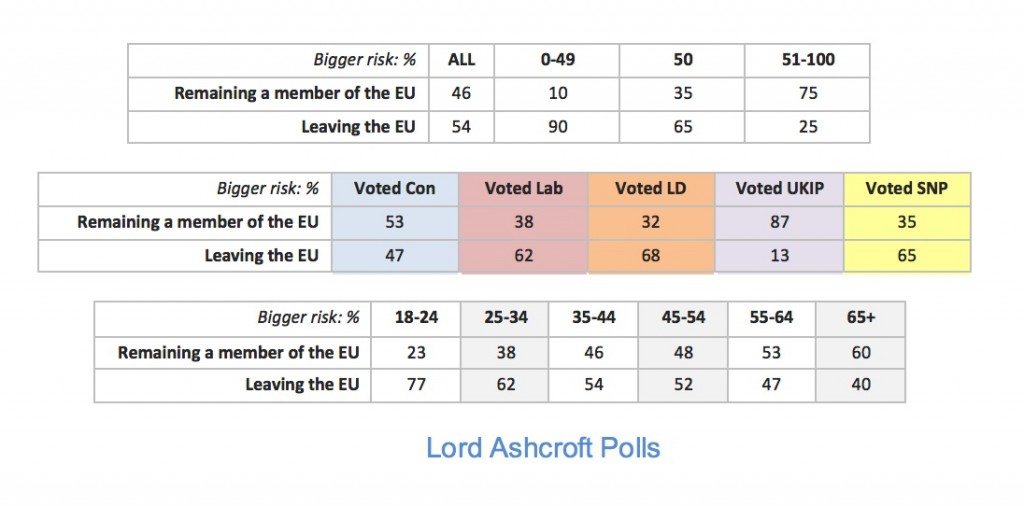

Despite the fact that a small majority put themselves on the Leave side of our scale, and warnings from the Leave campaign about how the EU might change for the worse in the future (expansion, further integration), most still saw leaving as the bigger risk.

A majority thought “the fact that we don’t know for sure what life outside the EU would be like for the UK” represented a bigger risk than “the fact that we don’t know for sure how the EU will develop or change if the UK remains a member”. Women thought life outside was a bigger risk by a 22-point margin, compared to eight points among men. Majorities of Conservative, Labour, Lib Dem and SNP voters thought this. Just over one third (34%) of those on the Leave side of the scale thought not knowing what life outside would be like amounted to a bigger risk than not knowing how the EU might change.

Overall, people thought leaving the EU was a bigger risk than staying by 54% to 46% (showing very little change since December, when the split was 53% to 47%). One quarter of those on the Leave side of the scale saw leaving as a bigger risk than remaining.

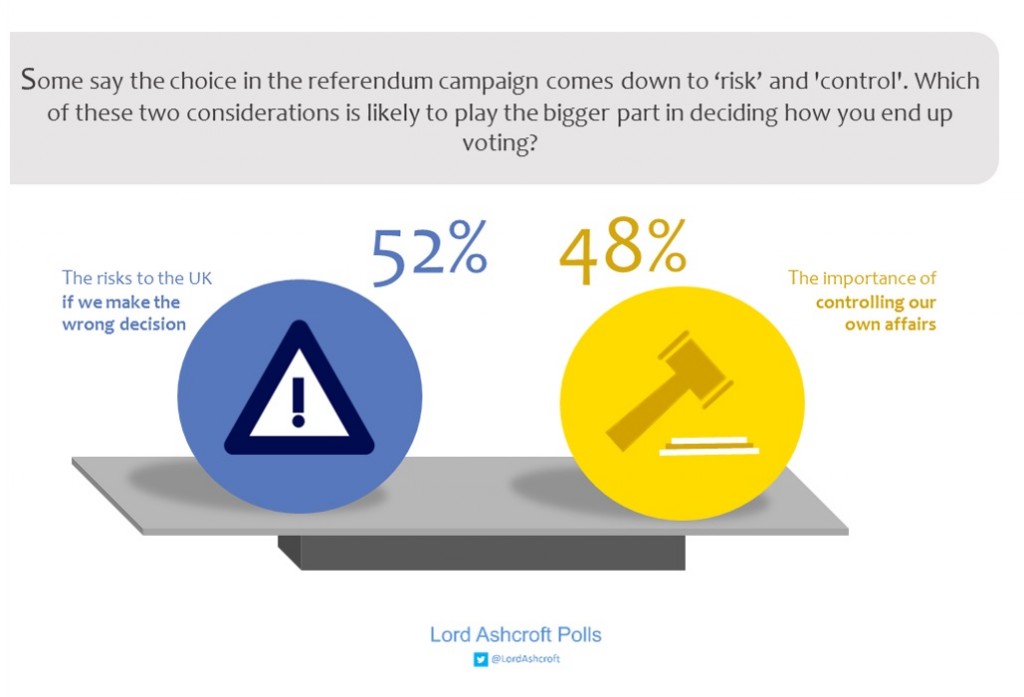

Which of these two themes – Remain’s ‘risk’ and Leave’s ‘control’ – is the most powerful?

A very small majority said “the risks to the UK if we make the wrong decision” was likely to play a bigger part in their voting decision than “the importance of controlling our own affairs”. Women thought this by a ten-point margin (though men thought the opposite by four points), and completely undecided voters by 28 points.

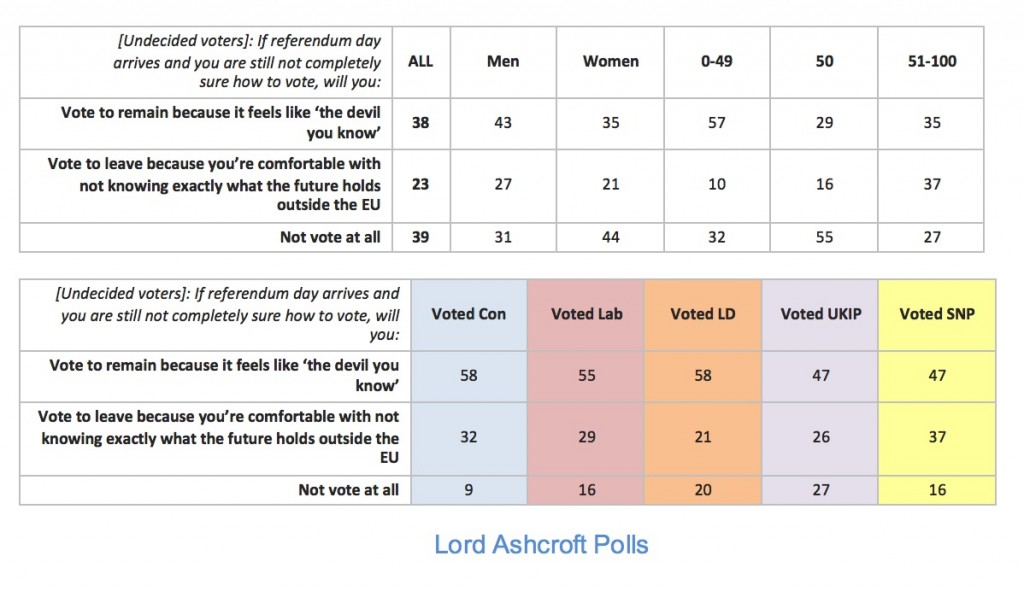

We asked undecided voters what they would do if election day arrived and they were still not sure which way to vote.

Nearly two fifths (38%) said they would vote to remain as it felt like the devil they knew; just under a quarter (23%) said they would vote to leave as they were comfortable not knowing exactly what the future holds outside the EU; the remaining 39% (31% of men, 44% of women) said they would probably not vote at all.

There are two possible interpretations of how the figures on risk relate to our Remain-Leave sentiment scale. One is that if a majority still think leaving remains the bigger risk, but opinion on the Leave side is hardening, some are becoming more determined to vote for Brexit despite the hazards: they want to take Britain out of the EU despite the risks.

The other interpretation is that people’s admission that they see leaving as a bigger risk than remaining is a signal not to treat their stated preference for Brexit as a firm voting intention.

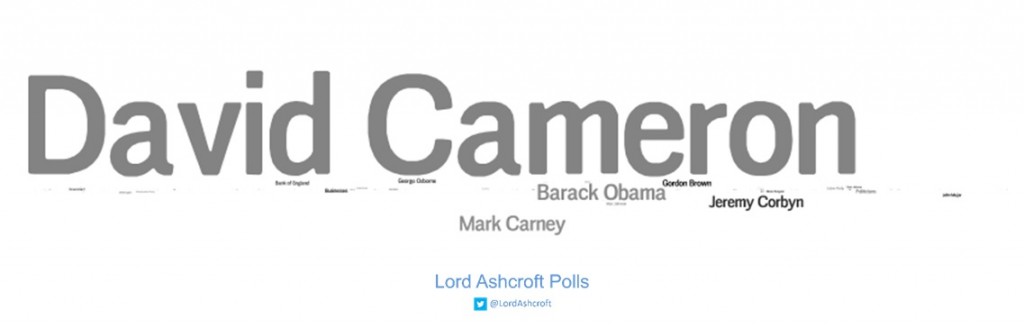

4: Boris and Dave dominate the debate

We asked people who, on each side of the debate, had done the best job so far of putting their argument across.

On the Leave side, Boris Johnson was named spontaneously by 1,707 respondents – more than four times as the next most mentioned campaigner, Nigel Farage (358). Michael Gove received 219 mentions, Iain Duncan Smith 104, David Cameron 41 and Donald Trump 40.

David Cameron dominated the Remain side, with 1,248 mentions. Both President Obama (199) and Mark Carney (187) were mentioned more often than Jeremy Corbyn (144). Gordon Brown (79) was named more often than George Osborne (54).

5: Each side’s message is clear (whether or not it is believed)

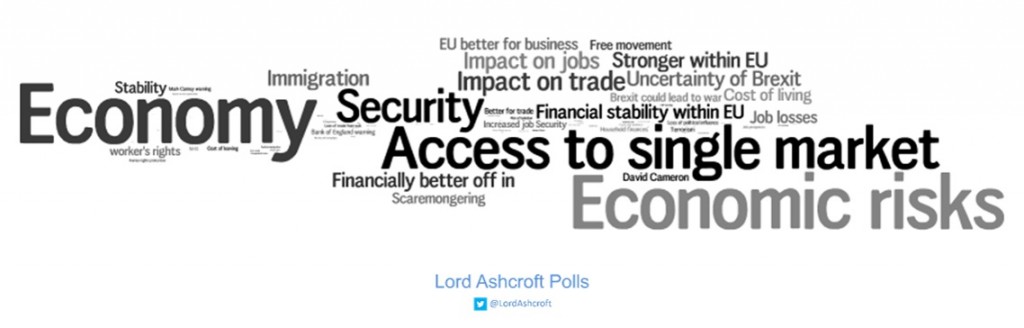

We also asked people which piece of evidence from each side had been the most compelling.

Messages from the Remain campaign were dominated by risks to the economy, including access to the single market, and the impact on jobs and trade.

The Leave campaign’s message was dominated by three themes: border control, control over the UK’s laws, and the cost of membership.

6: Instinct will matter more than facts

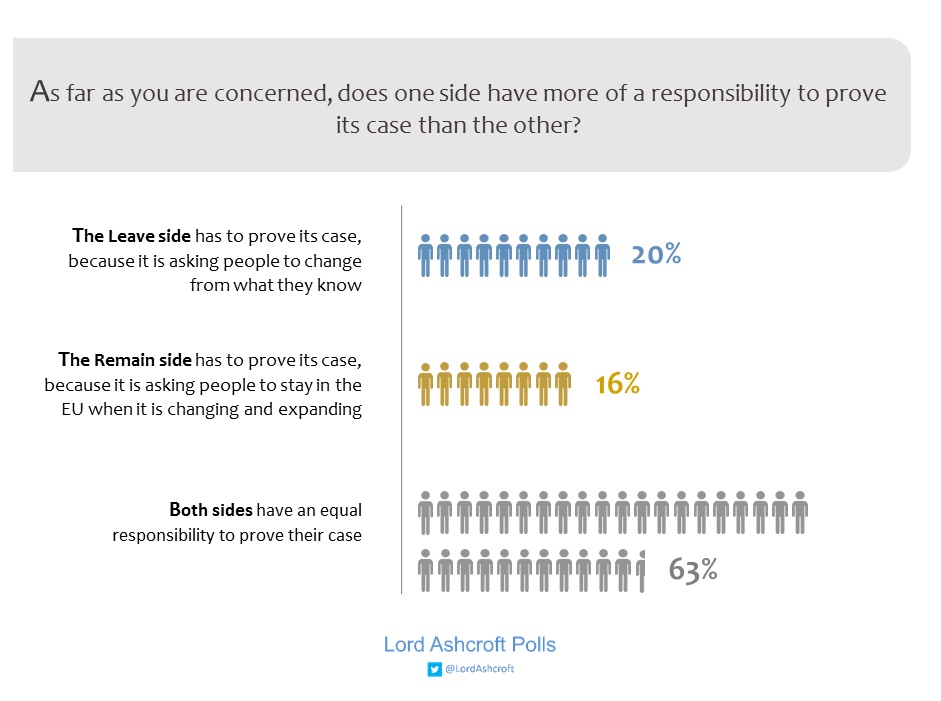

Nearly two thirds (63%) thought the two sides had an equal responsibility to prove their case – but the remainder were slightly more likely to say the burden of proof lay with Leave (20%) than with Remain (16%).

More than half said their “instincts about which is the right decision to take” would end up playing a bigger part in their vote than “factual information” (though more than six in ten eighteen to twenty-four year olds said facts would play a bigger part – the only group in which a majority thought this).

Just over half said they would decide on the balance of probabilities, rather than having to be convinced beyond reasonable doubt – though while those on the Remain side of the sentiment scale said they would go on probabilities by a 20-point margin, those on the Leave side thought this by only six points.

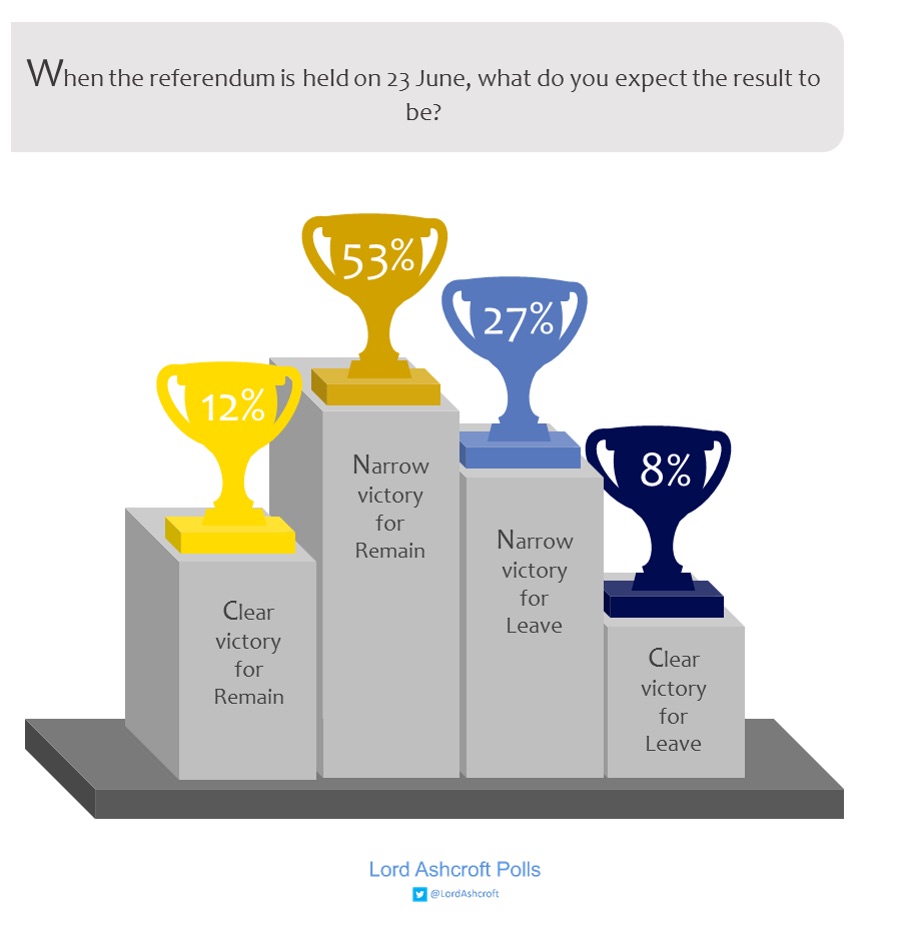

7: Most people expect a Remain victory…

Nearly two thirds (65%) expected a victory for Remain (though most thought it would be narrow). Those on the Remain half of the sentiment scale expected this by nearly nine to one. Those on the Leave side expected Brexit, but only by a six point margin: 47% of them expected Remain to prevail.

8: …but they can’t decide how much it matters

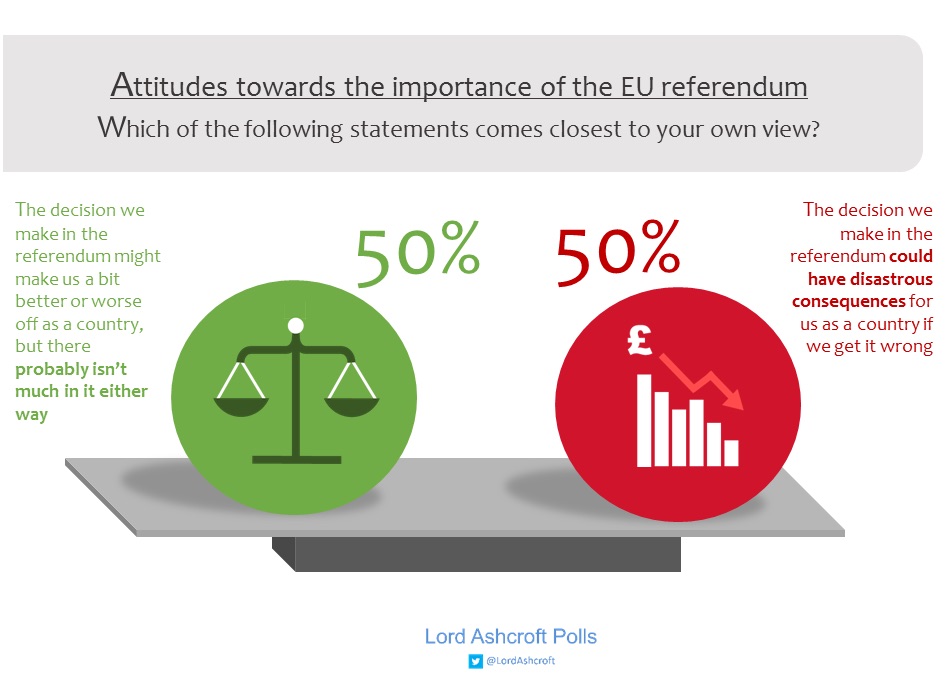

Finally, we asked how much was really at stake: was there little to lose either way, or did we face a potential disaster? On this, the country was completely divided.

5,009 adults were interviewed online between 13 and 18 May 2016. Results have been weighted to be representative of all adults in the United Kingdom.