Over the next nine weeks Lord Ashcroft Polls will visit every region of the country to find out what undecided voters are thinking about the referendum, what they have noticed and what has passed them by, what they make of the latest claims and interventions, what they take seriously and what they dismiss, whether they are any closer to making up their minds and what is pushing them one way or the other. This week: Bury, Rossendale and Norwich.

*

For the Remain camp, the week’s main event was the launch of the Treasury document claiming that households would be £4,300 a year worse off by 2030 if Britain left the European Union. This brought the usual complaints about any number in politics: “where have they got this random figure?”, “you can make statistics tell you anything”, “I just listen to that and think, give us some explanation, why will that happen?”, “he can’t even forecast for two years correctly, never mind fifteen years!”

But tellingly, the £4,300 figure was mentioned spontaneously in every group, and even though people were not sure they believed it, it worried them. Why does it stick in your mind if it might be nonsense? “Well, it’s a lot of money for any household, isn’t it?”

*

On the other side of the debate, the groups freely recalled not one but two figures. First, that “if we stay in we will have three million more immigrants than if we come out”. Though they were not sure over what time period they were expected to arrive, or where the figure had come from, this claim sounded plausible – especially given the migrant crisis, the persistent economic troubles in the south and the possible accession of Turkey.

The other number in common currency on the Brexit side was that Britain sends the EU £350 million a week – a figure that has been in the public consciousness for some time (though not universally: “it’s the amount it costs that worries me. Is it something like £10 billion a day? Or is it £10 million? Or £7 million. Anyway, I was shocked when I heard”). Not everyone accepted the £350 million figure at face value, wondering if it was gross or net, and few thought it was a clinching argument in itself, since (being undecided) they also thought EU membership brought some benefits.

But there were no takers for the idea that if Britain left, this money would be spent on public services instead: “John Redwood said they could spend the extra £350 million a week on the NHS. If anyone thinks they would really spend it on the NHS they need their head examined. It would go on tax cuts for businesses and getting rid of the deficit, not schools and hospitals.”

*

Most participants remembered receiving the official government leaflet (“the one that says ‘your Prime Minister wants you to stay in’”). Had anyone read it? “It looks a bit long”; “Oh it’s not too bad, there are lots of pictures.” “My cat scratched it.” “I’ve kept it on one side, I think it’s far too early. I will read it.” Of course you will, just like all the manifestos.

Not everyone had discarded the document. “It seemed a bit biased to me towards one way.” Maybe it was the title, Why the government believes that voting to remain in the European Union is the best decision for the UK. “It says we already control our borders. I thought, well, if that’s true we’re not doing a very good job.”

There was some indignation about the government spending quantities of taxpayers’ money (recalled at between £9 million and £27 million) supporting one side of the campaign. However, this was largely confined to those leaning towards Leave (“Mine’s gone back to 10 Downing Street with no stamp on it”), and a furious few who had never wanted a referendum in the first place and resented the burden of having to decide: “The government are giving us a choice in something but are spending millions of pounds trying to persuade us to go one way! It’s disgraceful.”

Not everyone was worried about this: “People always say they don’t know what the issues are, what the data is. You can’t have it both ways. If you want the information it’s got to come from somewhere so you’ve got to pay for it;” “The government have got a responsibility to the electorate, to tell people what they think.”

More importantly, “who is running the bloody country while all this is going on?”

*

These discussions illustrated a problem that both campaigns have. People demand facts (“I know everyone’s opinion. I want ‘this will happen’, ‘that will happen’”), but any attempt to present a concrete scenario about the future is met with scepticism or even incredulity, and even a yearning for more truthful humility: “In all honesty, how can we know? Why don’t they just say, this is what we think?”

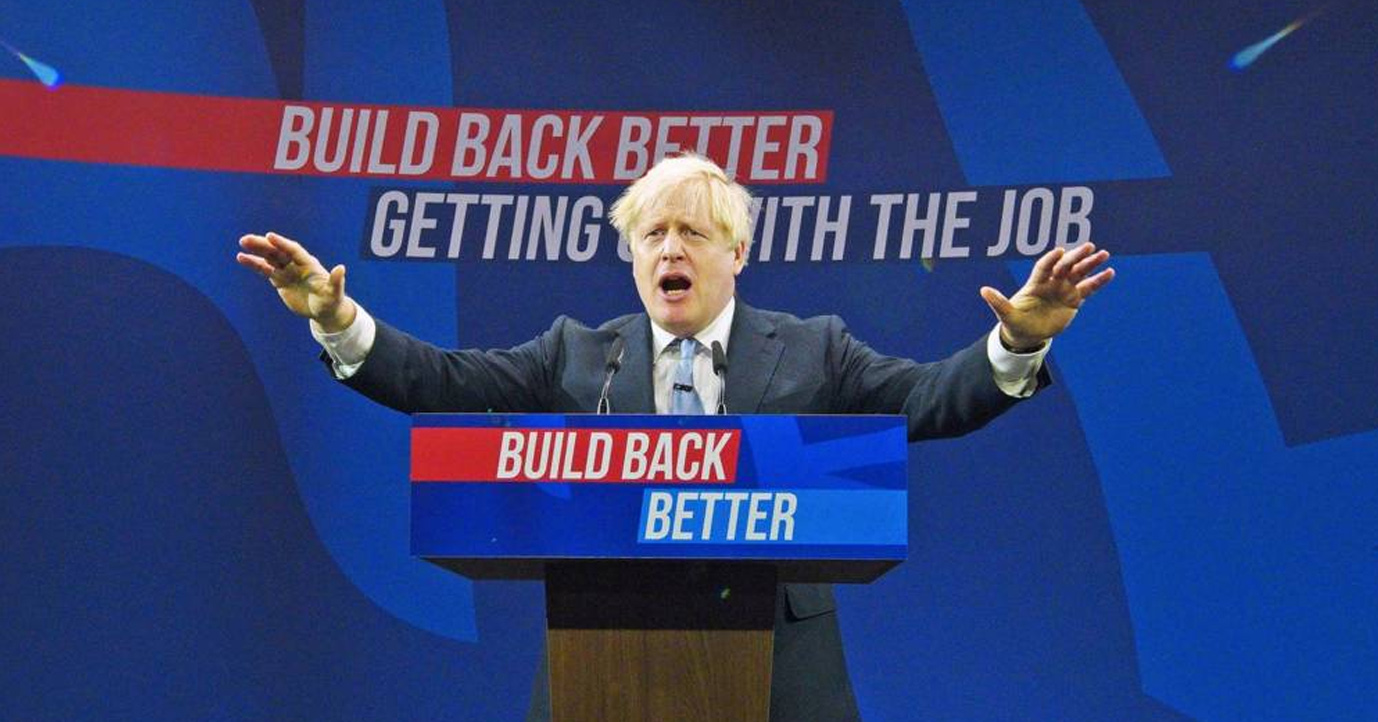

The inherent unreliability of “facts” about the future inevitably led people to look at the protagonists and their motives. Since everyone’s motives were suspect, this hardly helped. Cameron and Osborne wanted to keep their jobs; their opponents in the Conservative Party wanted to replace them (especially Boris, whom several people said reminded them of Donald Trump, or vice versa). Jeremy Corbyn had been more measured – “he said you might not think everything is perfect about the EU but on balance it’s healthier to be in” – or “grudging” and “half-hearted”, depending on outlook, but few were looking to him for direction. Companies and trade bodies would support whatever was best for them, not the country.

Meanwhile, President Obama would argue for “what suits America” rather than Britain’s interests, and anyway, “he’s not in office for long, is he?” The warning from Emmanuel Macron, the French economy minister, that outside the EU Britain would be “completely killed” in trade talks with China was “quite frightening” for some, but then again “he wants us to stay in because it benefits his country”; “he does make a point, but to be cynical, if the UK gets out of the EEC [!] the ninety-litre booze cruise comes to an end”. (Neither did they like his manner in his interview on Marr: “He is saying we’re very small and would be nothing without the EU. It was like a threat.”)

The groups had detected reservations about Brexit from Mark Carney: “He said it would have repercussions for the fragile economy and that worried me. MPs take their advice from the Governor of the Bank of England so his advice is worth taking on something like this.” But then again, “would the government let him say anything they didn’t like?”

Some felt defeated by the seeming impossibility of choosing between competing facts and personalities: “It’s like watching Match Of The Day. A player has gone down in the box, and two ex-professionals can’t agree if he’s dived or not, and if they can’t decide, how’s the referee supposed to decide? And the referee is us.”

*

At first glance, most in our groups saw leaving as a change and remaining as the status quo: “we know what ‘in’ is like”. When prompted with the thought, the idea that the EU itself might change – and would not necessarily stay as the devil we knew – was quite powerful. The most easily imagined change, and a worrying one for many, was expansion, particularly if it included Turkey: “when we joined it was six countries, a completely different animal”. The argument that remaining in the EU also involved change did not reverse the balance of risk, but evened things up somewhat.

This point was articulated this week in a speech by Michael Gove. We played a clip, which confirmed that the Justice Secretary was far from forgotten. “Is he the guy who kicked off all this schools business and then walked away from it? And now he’s come out against Cameron?” “I wouldn’t trust him.” “After what he did to education I could hang him up by his bollocks.”

If people were distracted by the messenger, the message itself was potentially effective. But it does mean that both sides could be accused of indulging in Project Fear: “He’s saying they’ll have control over us. He’s trying to scare people again.”

*

Most in the groups had seen the picture of Cameron making campaign calls alongside Lords Ashdown and Kinnock. This prompted some nostalgic smiles (“Neil Kinnock. My goodness. Neil Kinnock”), and reinforced the cross-party nature of the campaign, but this didn’t always help with the decision. For one thing, “there are probably different parties in the Brexit campaign as well”, and for another, the absence of party labels made the choice harder, not easier.

In fact, not being able to vote along party lines was one of the main reasons the decision was so vexing, not just for Conservative voters but for Labour supporters who felt they were not getting a clear lead. “It makes it more difficult. I usually vote with a party but you can’t do that this time and we’re not getting information.” For some, the fact that a politician from another party supported the position they otherwise leaned towards was more disturbing than reassuring: “Cameron supporting remain worries me actually. I think, ‘why are you in favour?’”

*

How did people expect finally to make up their minds? “I’m waiting for that lightbulb moment. I’m just hoping someone will say something and I’ll go ‘that’s it! I’m in!’ or ‘that’s it! I’m out!’. Like yesterday, my boss, when her child didn’t get into the school she wanted, she said ‘that’s it, I’m out’.”

Some wanted to see the arguments clarified once and for all: “Are we going to have a live TV debate between those who are Brexin and Brexout?”

Meanwhile, in some quarters things were getting tense. “I was at a dinner party, and we were all friends, and we got onto Europe and it turned into a huge row. Two people ended up going home!” Crikey. Which ones? “Oh, the stayers left and the leavers stayed.”