David Cameron is in Brussels to finalise his renegotiation of Britain’s EU membership terms. Many voters would never be persuaded to stay whatever he came back with, but as my recent research found, some undecideds could be swayed if the PM convinced them he had won a good deal.

But the question of Britain’s place in the EU is about more than the precise restrictions to benefits for new migrants, or any commitment to cut back on excessive business regulations. My new polling among more than 28,000 voters throughout Europe helps to explain why.

Most European voters want the UK to stay in the EU. This is particularly true in Ireland, our closest neighbour, of old allies like Malta and Portugal, and in new accession countries like Lithuania and Romania. Overall, six in ten respondents throughout the EU said they would prefer the UK to remain, with thirty per cent saying it didn’t matter either way and only one in ten saying they would rather we left.

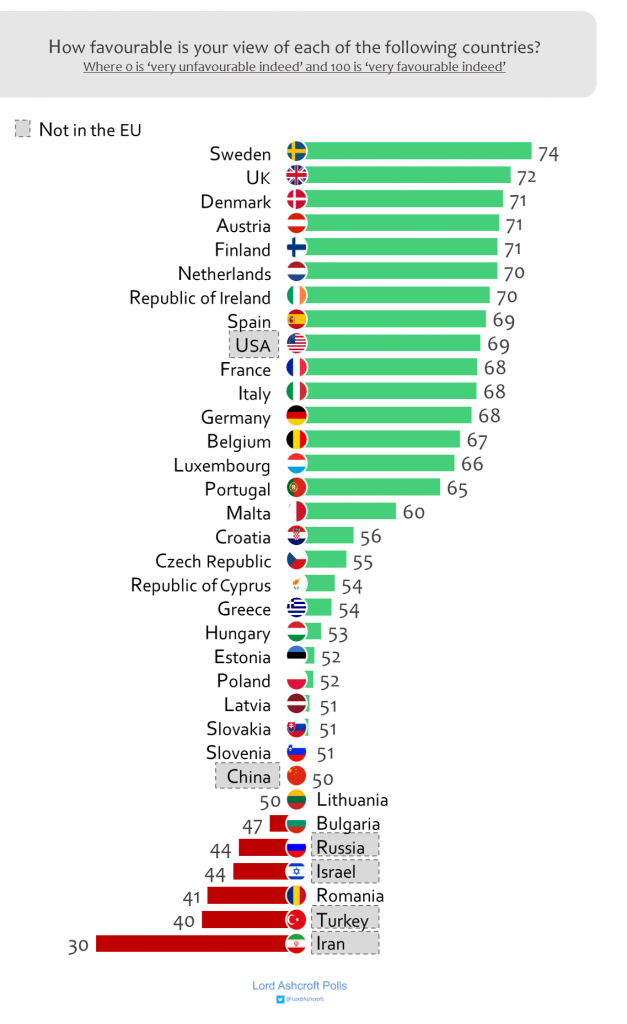

This is not just because we are a net contributor to the budget – they actually seem to like us. When people gave favourability ratings for each of the other EU countries, plus some others, the UK came second to Sweden. The youngest participants, aged eighteen to twenty-four, gave us more positive ratings than any other age group.

Europeans see us as polite, patriotic and cosmopolitan, though rather status-conscious and (especially for those in the Eurozone) arrogant. (And the Greeks are unusually likely to think of us as binge drinkers, for some reason.)

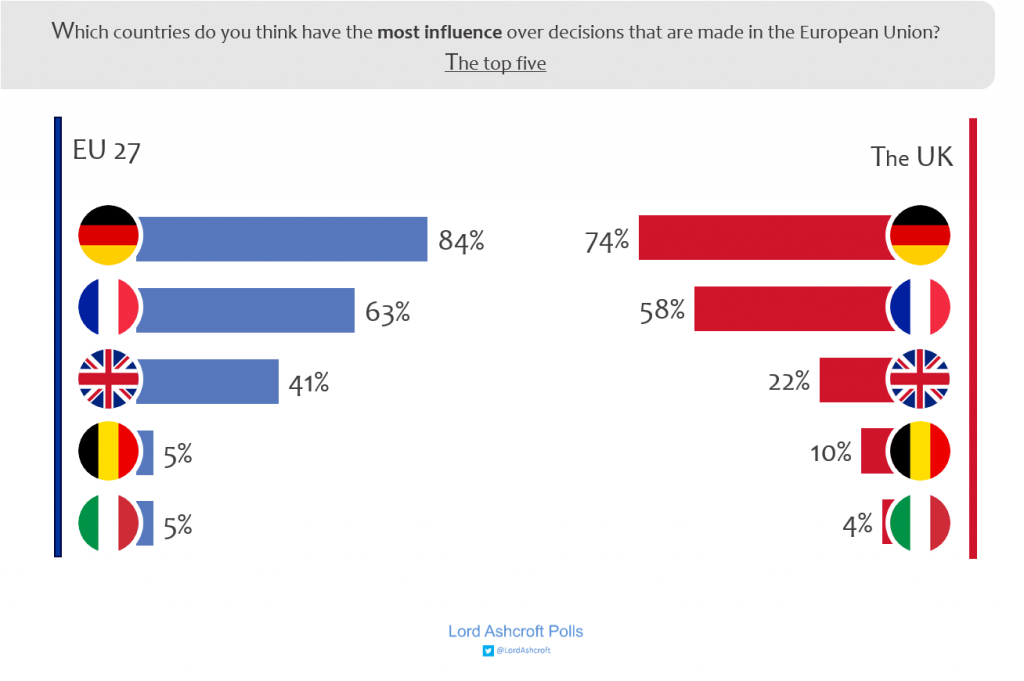

As my focus groups in EU capitals have shown, many admire Britain as a country that stands up for itself. It may overstate the case slightly to say, as someone did in Amsterdam, that the UK is “the only European country with an army”, but they think Britain has clout. People in Europe think we are the third most influential EU member, after Germany and France (though people in other countries were twice as likely as UK participants to think we had a big say over decisions). They fear Brexit would be a blow to the EU’s prestige, and could trigger further departures.

Despite this, I found some ambivalence about the principle of negotiating to keep Britain in the fold. People outside the Eurozone and in the “New European” countries who joined in 2004 or later were the most willing to change the UK’s terms, but in the more established countries majorities agreed that “if the UK does not like the terms of EU membership it should leave”. Three quarters of Austrians and Luxembourgers thought this, as did two thirds of Belgians.

When it came to the UK’s specific negotiating demands, there was little resistance in most cases – suggesting that, at least as far as European voters were concerned, Cameron might have been able to win further reforms had he pushed harder. People in Eurozone countries were nervous about guaranteeing that the UK would never contribute to euro bailouts, but changes to welfare rules and the idea of more powers for national parliaments were largely uncontroversial – provided all countries, not just the UK, benefited from the new provisions.

But perhaps the most revealing finding was that, of all the things on the Cameron’s agenda, exempting Britain from “ever closer union” aroused the most opposition. Some British voters think this aspiration is the pernicious rubric that reveals the Union’s wicked intent; for many more, it is dusty rhetoric or meaningless waffle with no practical consequences. It matters that many Europeans do not see it this way.

People elsewhere in the EU are not starry-eyed about the institution. Many complain about unnecessary rules and regulations, or (at least in the North) having to pay for other countries’ economic problems. But they seem more inclined than British voters to regard these things as part of the shared sacrifice necessary to a valuable common endeavour. Accordingly, they view the more transactional British approach with distaste. “They agree with Europe when it’s good for them, and disagree when they don’t like it!”, as one of our Parisian participants complained. If everyone behaved like this, they think, where would it all end?

Depending on when they joined, many see the EU as their membership of the West, putting them at the heart of the international community, or as the guarantee that Europe will not revert to state of conflict that has been a perennial feature of continental affairs in their own lifetime, or their parents’. This gives rise to an emotional attachment to the EU itself that British people tend not to share, even if they think they are better off in it than outside it.

For that reason, Britain is never going to recreate the EU in its own image. We will not turn it back into the trading bloc many think we signed up to forty years ago. Most of our fellow members have a different view of what they want the EU to be like, and there are more of them than there are of us.

So the deal that emerges from Brussels at the end of this week should matter less to British voters than how they see things in five, or ten, or twenty years from now. We must decide whether Britain will benefit from staying in the EU, even if the other members have a different view of its aims; and whether we trust not just Cameron but those who come after him to keep Britain out of future developments we do not like. Once the summit circus is over, these questions will be at the heart of the debate.