This article was first published in The Independent.

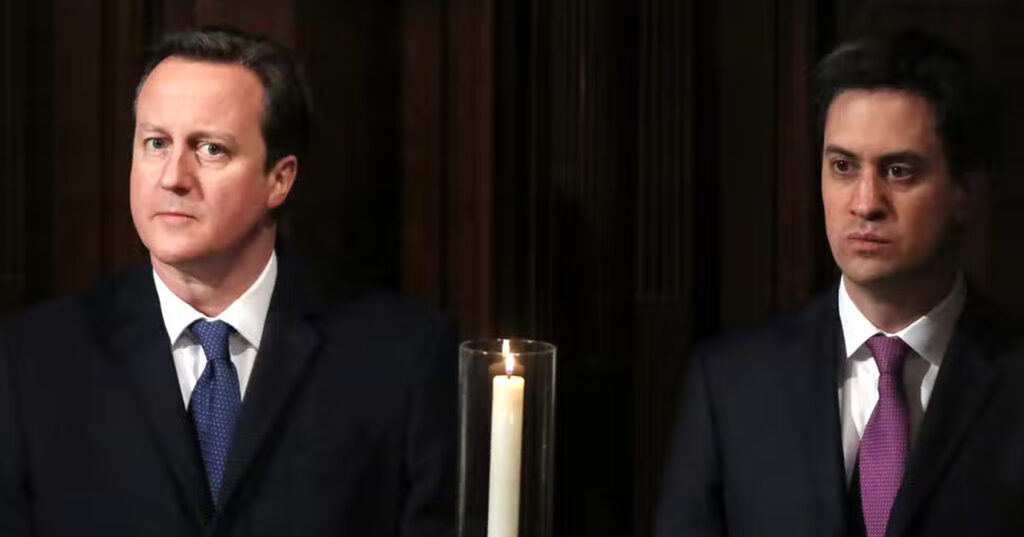

“I don’t understand it,” said a chap in one of my focus groups a few days ago. “People think David Cameron is pretty good, and they think Ed Miliband is a muppet. So why is it so close?” Why indeed. It is a question to which books and theses will be devoted in the months to come. But I think we already have a good idea of the answer.

My research over the parliament has analysed the importance of different factors to people’s choice of party, and how these have changed over time. Throughout the parliament, David Cameron has been seen as better PM material than Ed Miliband and, for most of that time, the Conservatives have been more trusted than Labour to run the economy.

In fact, the Tory lead on both questions has grown over the past couple of years as the economy improves and doubts grow about whether Labour can safely be let loose on the public finances.

That would usually be enough to see a governing party comfortably into a second term. But as time has passed, my analysis shows those things have become less important, relative to other factors, in determining people’s preference for Labour or the Conservatives. At the same time, issues like welfare reform and immigration have risen in salience, but the Tories’ advantage on them has fallen.

And, crucially, questions about the parties’ motivations – whether they want to help ordinary people get on in life, share voters’ values and are “on the side of people like me” (rather than, well, people like me) – have edged upwards in importance as the Labour lead on them has grown. Some lament that politics has been taken over by charts and the crunching of numbers and the targeting of tiny voter groups, and this might sound like more of the same. But it illustrates a much wider question, and one that is eerily familiar.

In 2010, when I was running the Tories’ private polling as deputy chairman, the election boiled down to this: even with a weak Labour opponent, how many voters would an attractive new leader persuade to vote for an essentially unchanged Conservative Party? We got the answer: not enough.

Five years later, the same question is being asked again, as though to make sure. As I explained in Minority Verdict, my account of the last election campaign, many voters wanted change but felt Labour’s over-the-top caricatures of the wicked Tories rang a bit too true for comfort. Others voted Tory with a degree of doubt or even trepidation.

Only in government would the Tories be able to prove their claim that they were no longer the out-of-touch party booted out of office 13 years earlier, and that the change went beyond the person of Mr Cameron.

Since 2010, the Tories have restored their reputation for taking tough decisions, if sometimes with a bit too much relish. And given the fiscal position, Cameron deserves credit that the election is even competitive. Uniquely among the leaders, he commands higher approval ratings than his party. But this signals that, in important respects – at least in the eyes of voters – Cameron has not been able to change the party he leads. People are less likely to say the Tories share their values, stand for fairness or would look after public services like the NHS than when they came into office.

Do these touch-feely things matter? Well, it depends whether you want to win an election or not. The extent of people’s doubts about the Tories’ values and motives explain why the party has been so long confined to the third of voters it can currently muster.

There are some parallels with Labour’s experience. Though Tony Blair was a completely different Labour leader to anything before or since, he did not change his party any more fundamentally than Cameron has changed his. Nothing was heard of New Labour under the premiership of Gordon Brown, its supposed co-architect, and Miliband has buried it altogether. Many within Labour seem to regard their party’s most sustained period of electoral success not as a golden age but as an aberration.

So if Blair’s changes were not fundamental, why was he so successful? Because his party was in a better position to begin with. People already thought Labour’s heart was in the right place: add a leader who understood middle-class aspiration and looked like he knew what he was doing (in stark contrast to the Tory shambles that then prevailed) and they were off to the races.

Twenty years later, the voters must decide between a government led by a Labour Party once again seen as well-intentioned but lacklustre, and a Conservative Party whose shortcomings are as familiar as its strengths. Paradoxically, the fact that the voters find the choice so uninspiring has given rise to the most exciting general election I can remember.