Towards the end of the last parliament a cartoon showed a lady asking her husband, “Is it possible to be sick of an election before it’s started?” Many will have the same thought long before – 365 days from today – we choose our next government.

For David Cameron, though, the year will feel terrifyingly short. Last night the PM reassured his troops that they can take on UKIP – the biggest worry for many in the party – by reminding voters that only the Conservatives can deliver a referendum and real change. Grumpy though some Tories are, they know Cameron remains their biggest electoral asset. They also know there is no alternative; as my polling has shown, Boris is popular but no silver bullet.

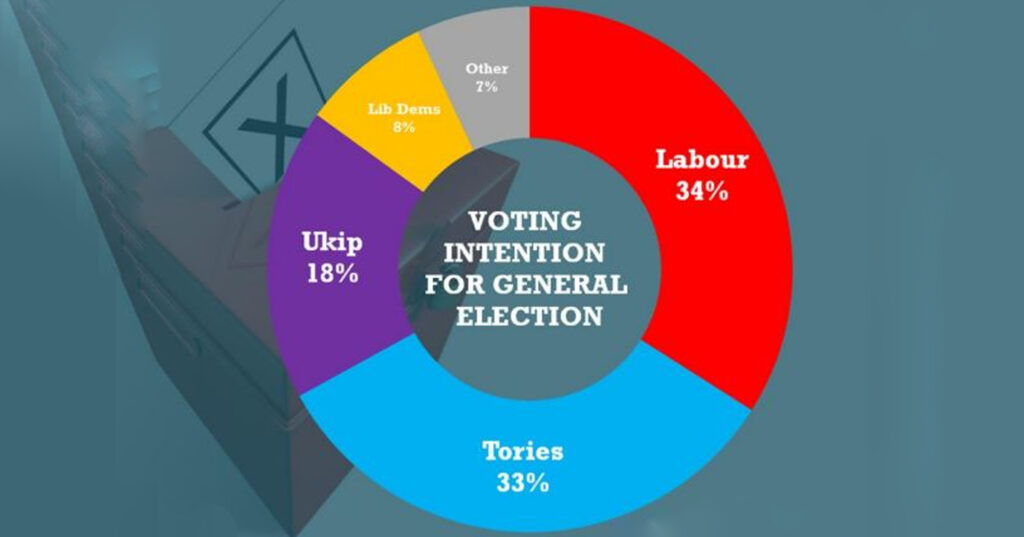

Cameron remains more popular than Ed Miliband and the Conservatives are more trusted than Labour to run the economy. The Tories hope these things will matter more to voters as the decision gets closer. Meanwhile, jitters will grow if Labour’s lead persists as the year wears on.

It will take more than 12 months to change many voters’ view that the Tories are not on their side. In the meantime, they must show more clearly what a national recovery could mean. My polling has found people are more likely to think a Tory government would benefit Britain than to believe it would be good for them.

Nick Clegg will also feel the year rushing by. To most voters the Lib Dems have betrayed their principles, or sunk without trace, or both. Achieving office has also cost them the votes of the none-of-the-above brigade, probably for good. That means the Lib Dems must define a national purpose for themselves. This – though Tories blame them for thwarting their most beloved schemes – is proving a struggle. They must hold on to as many as they can of the 57 seats they won in 2010 on perhaps half their former national vote share; perhaps more than any other party, their fate will be determined in the marginals.

Ed Miliband will be counting down the days more impatiently. Labour’s current lead would see him comfortably into Downing Street. But he knows governing parties tend to recover ground in the months before an election. He needs to show Labour have learned their lessons on the economy and that he has more to offer than complaints about how expensive everything is. Labour have done little to allay the fear that they would spend more than the country can afford and undo what progress the coalition has made on things like tackling benefit dependency.

Labour will ask: “are you better off than you were five years ago?” But a second question – “wouldn’t you be better off with us?” – is implied. Miliband cannot yet bank on the answer.

For Nigel Farage, too, 7 May 2015 cannot come soon enough. For UKIP, European Parliament elections bring attention by the truckload, but they have always marked the high points of the party’s success. Though an ideal conduit for the blowing of mid-term raspberries, Farage will need to explain why UKIP are worth voting for when more is at stake.

Stickers are already printed bearing the legend “Don’t blame me, I voted UKIP”. Fine, for those who want to opt out of the decision. But what to say to people who want their vote to count?

Whether they wish the coming year were long or short, all the parties have to contend with public weariness and cynicism – not just about the behaviour of politicians but over whether politics itself can do much to change things, at least for the better.

This threatens the established parties: in a world where governments seem to have so little power to solve problems and improve our lot, what does it matter who is in charge? We might as well vote for someone who cheers us all up.

How should the parties react to this attitude? Like this: show a bit of humility, keep things in proportion, and treat the voters as grown-ups. Don’t overclaim, either about what you have done or what you can do. Don’t tell people you’re going to change their world, or that your opponents would shatter it – still less that they would do it on purpose. Talk to people about the things they care about, rather than repeating what you hope they can be made to care about (and then fretting that the public are “disengaged”).

For the voters, it is going to be a long year. The first thing they will need persuading of is that it matters who wins.

This article was first published in the Daily Mail.