The mood at the Liberal Democrat Spring Conference this weekend will perhaps be more cheerful than at any such gathering since the start of the coalition. The Eastleigh by-election apparently vindicates Nick Clegg’s approach to government, and his party’s approach to campaigning.

His activists will be relieved to think that pavement politics is back; that despite the polls, strong local government and an invincible leaflet-dropping network will see many or even most of their incumbent MPs safely back to Westminster in two years’ time. Certainly the Eastleigh victory was a considerable achievement for the Liberal Democrats, and there is no doubt, as my research has suggested for some time, that the party remains stronger as a local force that the national numbers suggest.

But that is not the whole story.

A general election does not amount to hundreds of simultaneous by-elections, and the Liberal Democrats will not be able to treat it as though it does. Localness matters, but a general election decides who walks up Downing Street. Moreover, the party has ceased to be the automatic repository for protest votes, as it was in 2010 and before. Whatever the Lib Dems say in their scattered municipal bastions, they have to have a national story. Clegg must have something to say about the Liberal Democrats and government.

This is arguably the most difficult of the respective challenges before the three parties. The Conservatives need to expand their support at a time of austerity, appealing simultaneously to disaffected Tories and those who have never voted for the party before. Labour must set out an economic alternative that does not involve spending and borrowing more than the country can afford, and show that they have learned the right lessons from their time in government.

The Lib Dem dilemma, though, is more far-reaching. The title of this project is not intended to be facetious. Nick Clegg must define his party’s purpose. The Liberal Democrats have always espoused the virtues of coalition government, but lost more than half their support the moment they joined one. The voters have punished them for achieving what they always aimed to do. Where does that leave the third party? Are they coalitionists first and foremost, helping to implement tough economic reforms in the national interest, aiming to moderate the instincts of their partners in government – of whichever party – while negotiating for some of their own policies to be adopted? Or should they distance themselves from the Conservatives, setting out a distinct, left-leaning policy programme in the hope of winning back the voters they have lost?

I wanted to look in detail at this question, the answer to which will play a significant part in determining the story of politics up to the next election and beyond. In order to do so I have conducted a poll of more than 20,000 people, allowing detailed analysis of Lib Dem voters, those who voted for the party in 2010 and have defected in one direction or another, and those who did not support the party last time but might consider doing so in 2015. Focus groups among each segment revealed more about their attitudes and motivations.

Remarkably, only one in twenty British adults both voted for the Liberal Democrats in 2010 and say they would do so in an election tomorrow. These are true Loyalists: they think the party shares their values, stands for fairness and has the best policies for getting the economy growing and creating jobs. They are far from uncritical of the party or Mr Clegg, however, often complaining that they seem invisible and powerless. They struggle to name any policy achievements – the higher Income Tax threshold is the best known (though most could not recall it or associate it with the Lib Dems unprompted), but the Pupil Premium seems barely to have registered. Nevertheless, these voters are glad the Lib Dems are in government, and have some sympathy for Nick Clegg’s position. They are the most likely to mention their local MP, of whom they nearly always think very highly, and though this would not often be a decisive factor, a strong local presence has the effect of winning the party a hearing on broader arguments about its role in government. They are very open to the Lib Dems’ likely election pitch that they went into the coalition for the right reasons, achieved some good things in difficult circumstances, and that the more votes they get the more they will be able to do.

A smaller number of people who did not vote Lib Dem in 2010 – 4% of the electorate in total – say they would vote for the party in an election tomorrow or consider doing so in future. This diverse group has no strong uniting factors, and seemed to be less politically engaged (though in an open-minded, rather than a cynical way). In essence, they like the coalition government and the Lib Dems’ presence in it, think that being in office has enhanced the party’s credibility, and feel the Lib Dems represent the middle ground – and therefore, people like them.

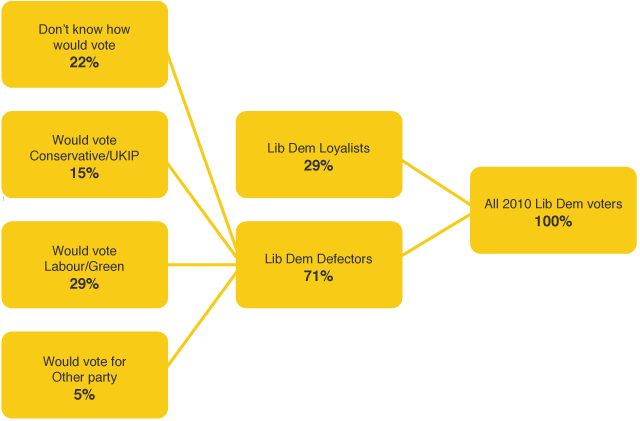

The Defectors are rather more numerous. More than seven in ten of those who voted Liberal Democrat in 2010 now say they will vote for a different party, or do not know how they would vote. There are three main varieties of Liberal Democrat Defector.

Pollsters have usually found that people who vote in one election, but say they are not sure how they will vote in the next, are likely to return to their original party. This seems likely for many of the Lib Dem Defectors to Don’t Know – half of them say they would vote for the party again when asked specifically about their own constituency. The remainder, however, seem equally open, or resistant, to all sides. Their strongest uniting factors are that they do not think Labour shares their values, or that the Lib Dems are competent and capable – but most of those who think this also do not know whom they most trust to manage the economy. The Lib Dems have lost their confidence, but nobody else has yet won it. Many of them were probably disaffected in 2010, and are now unsure where to take their disaffection next.

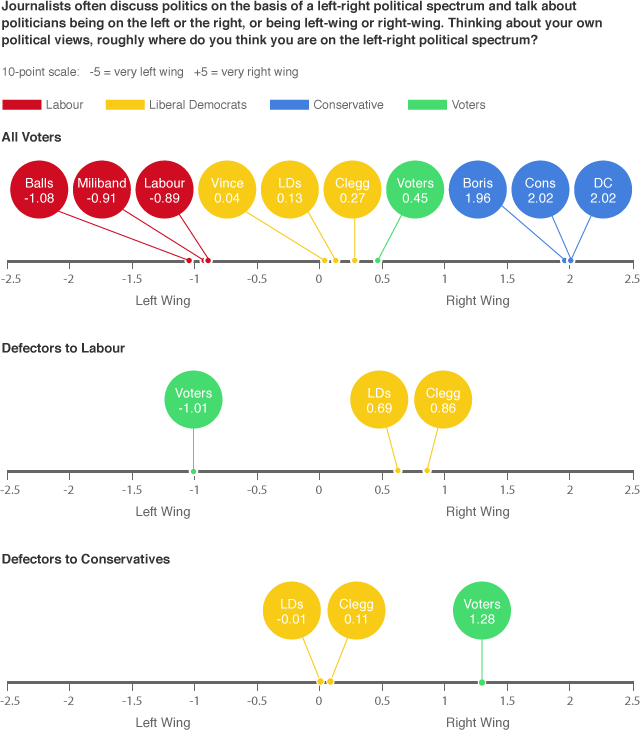

A fifth of those who have gone to another party, or 15% of all 2010 Lib Dem voters, say they would vote Conservative (8%) or UKIP (7%) in an election tomorrow. The things that these Defectors to the Right (to put it loosely) have most in common is the view that the Conservatives are the best party to manage the economy, and most of those who think this also think the Tories share their values and say a Conservative majority is their preferred election outcome. However, these Lib Dem-Conservative Defectors are less likely to say they are sure how they will vote than voters as a whole, or other Conservatives. Indeed, when asked about their own constituency, they are the most likely to revert to the Lib Dem column. They are more likely than other Defectors to think the Lib Dems have substantial influence within the coalition, and they rate the party much more positively than voters as a whole on factors like being on their side and standing for fairness. Though Conservative leaning in attitude, many of them think the Lib Dems have had a taming effect (though few can think of anything specific they have achieved).

While most Defectors to the Conservatives say the coalition has been about the same as they expected or better, two thirds of Defectors to UKIP say it has been worse. They also rate the Lib Dems lower on a range of positive attributes (especially “will do what they say”) than voters as a whole. They could think of little or nothing the party had achieved in government and were inclined to dismiss successes like the higher tax threshold, saying it hardly makes up for other tax rises, spending cuts, and the higher cost of living.

Two fifths of Lib Dem voters from 2010 have switched to Labour or the Greens – loosely, Defectors to the Left. These voters put themselves further to the left on the political spectrum than voters as a whole, and they put the Lib Dems and Nick Clegg further to the right than others do. The thing they have most in common is the view that Labour is the best party to manage the economy. Eight in ten of those who think this would prefer a Labour government after the election, and of this subgroup nine in ten say Labour shares their values – something they almost certainly thought when they cast their votes for Clegg three years ago.

Defectors to the Left think the Lib Dems have little or no influence within the coalition, and rank the party lower than average on keeping its promises (though higher than most on standing for fairness and equal opportunity, and having its heart in the right place).

Of all Defectors from the Lib Dems, those switching to Labour are the most likely to say they are sure how they will vote. They have been unhappy with the coalition from the beginning, and argue that the party should have joined forces with Labour, or stayed our and forced a second election, rather than formed a government with the Conservatives. Though they grudgingly say the coalition is less bad than an undiluted Tory government would be, or concede that one or two Lib Dem policies are now law, for most of them this is beside the point – as far as these voters are concerned, it is the Lib Dems’ fault that the Conservatives are in office at all. For this the party cannot be forgiven – and to vote for them again would be to risk a re-run of 2010.

The decision to enter coalition with the Conservatives did not so much cause the Lib Dems’ weakness as expose it. In this sense the party’s problem is analogous to the financial crisis. Lib Dem support in the years before 2010 was a bubble; it was over-leveraged, with inflated commitments it never expected to be asked to meet. Worst of all, these expectations were contradictory. A few people voted Liberal Democrat because they agreed with what the party stood for. Some voted because they were not Labour, and some because they were not the Tories. Rather more supported them because they were neither.

In particular, and crucially, the Lib Dems attracted a group of voters who did not want to vote for Gordon Brown and thought they had the luxury of voting against Labour without helping to elect a Conservative government. These people are numerous, and furious. What the Lib Dems have achieved, or how different from the Conservatives they can claim to be, is for them neither here nor there. As far as these people were concerned, the Lib Dems’ most important job – their only job – was to keep the Tories out, and now look what they’ve done.

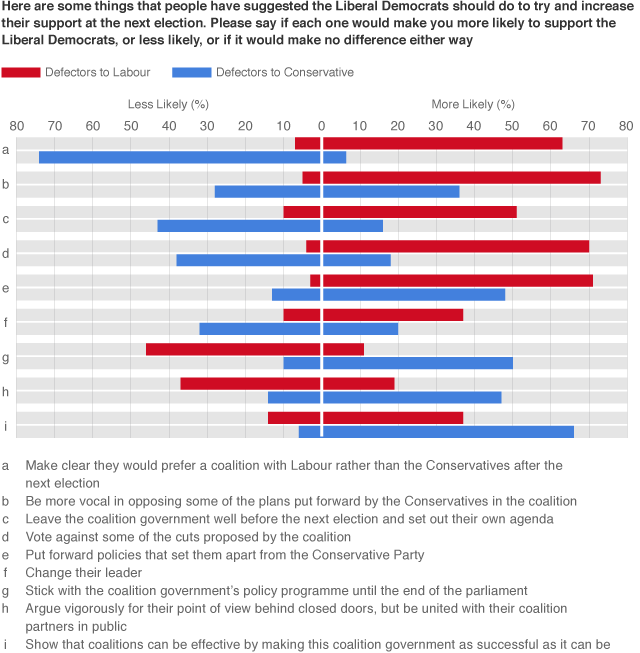

Some of these voters say they would be prepared to listen to the Lib Dems again if they distanced themselves further from the Conservatives, set out a distinctively left-leaning agenda, and found themselves a new leader (not because a better candidate is on hand, but because a sacrifice is needed to show the party’s contrition).

The Lib Dem dilemma, then, is to decide how far to go in trying to win back people who have largely made up their minds to support Ed Miliband, and indeed only voted Lib Dem in the first place as a left-wing alternative to Labour. The more they do so, the less success they will have with the smaller but much more biddable moderate voters, who are also open to the Conservatives, want the party to play a constructive part in government and would be unimpressed with the antics that the angry left require.

The party will no doubt make the most of its local credentials wherever it can. This will certainly weigh with some voters, but we found that when it came to a general election the main effect of popular MP was to win the party a hearing on wider arguments about the party’s role in government; it would not often be a decisive factor for those reconsidering their vote, particularly for those whose sympathies lie with Labour.

Conservatives will hope that the Lib Dems choose to do most of their fishing in places like Hornsey & Wood Green, in the People’s Republic of Haringey – ideally with a great deal of success, but if not, at least loudly enough for Tory leaners to notice and be put off. The recent evidence, such as loud demands for a “mansion tax” and apparent opposition to further welfare reform, suggests that despite Nick Clegg’s centrist tendencies the party is indeed looking in this direction. If that is the case, long may it continue.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives must be careful not to solve Clegg’s dilemma themselves. Despite everything, the Lib Dems’ brand values – the sense that they stand for fairness and ordinary people – remain surprisingly strong. For the Conservatives to learn the wrong lessons from Eastleigh and exclusively pursue the UKIP leaners would be to leave the part of the field occupied by moderate centrist and even centre-right voters – who want responsible and economically conservative government without the strident tone that can all too easily go with it – wide open to the Lib Dems. The Tories must not make the Lib Dems’ decision for them. While Nick Clegg’s party have a choice, there is always the chance that they will make the wrong one.