It is a frequently heard complaint in Westminster that political reporters and commentators do the public a disservice by obsessing over trivial “process stories” at the expense of things that actually matter.

Certainly it can be exasperating when, as has happened recently, journalists write unhelpful process stories and the following day criticise the government media operation for the proliferation of – guess what – unhelpful process stories. Of course, complaining about the media is not likely to get you very far in politics. And the best way to stop them reporting trivia is to make sure they have something significant to report instead.

That said, how much of this political froth do people notice? Last week I conducted an experiment to find out which recent political stories had got through to people, and whether they were more likely to recall the substantive or the trifling. Half the sample in my online poll were asked to write a brief description of any stories about political parties or politicians they had heard about in the last few weeks or months, whether they thought the story was important or not.

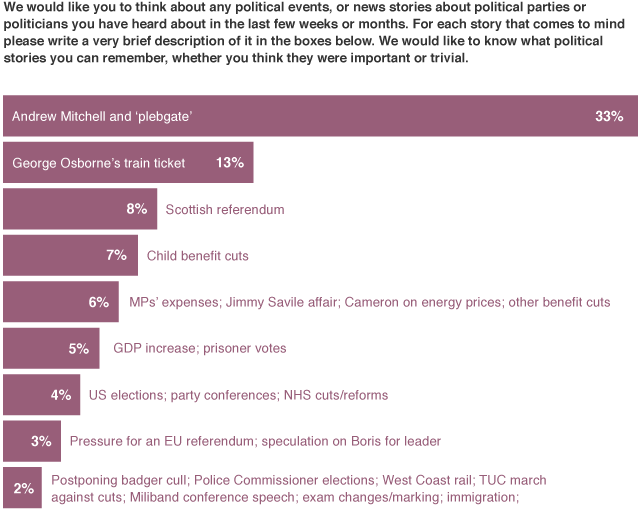

It is worth noting at the outset that 41% of respondents could not recall a single thing. The two stories most likely to be recalled spontaneously were perhaps at the trivial end of the spectrum, though the partisan would claim they highlighted important truths. Far ahead of the pack was Andrew Mitchell’s contretemps with a Downing Street policeman, recalled by 33%. Next, on 13%, was the misunderstanding over George Osborne’s train ticket. Eight per cent remembered a story about the Scottish referendum, and 7% referred to Child Benefit cuts. MPs’ expenses, the Jimmy Savile affair, David Cameron’s announcement on energy prices, and other welfare reforms were mentioned by 6%.

One in twenty mentioned the GDP increase and the end of the recession; the same proportion recalled stories about prisoner voting. Fewer than one in thirty-three mentioned pressure for an EU referendum or speculation about Boris Johnson wanting to lead the Conservatives; the postponed badger cull, the Police Commissioner elections and Ed Miliband’s conference speech were mentioned by one in fifty.

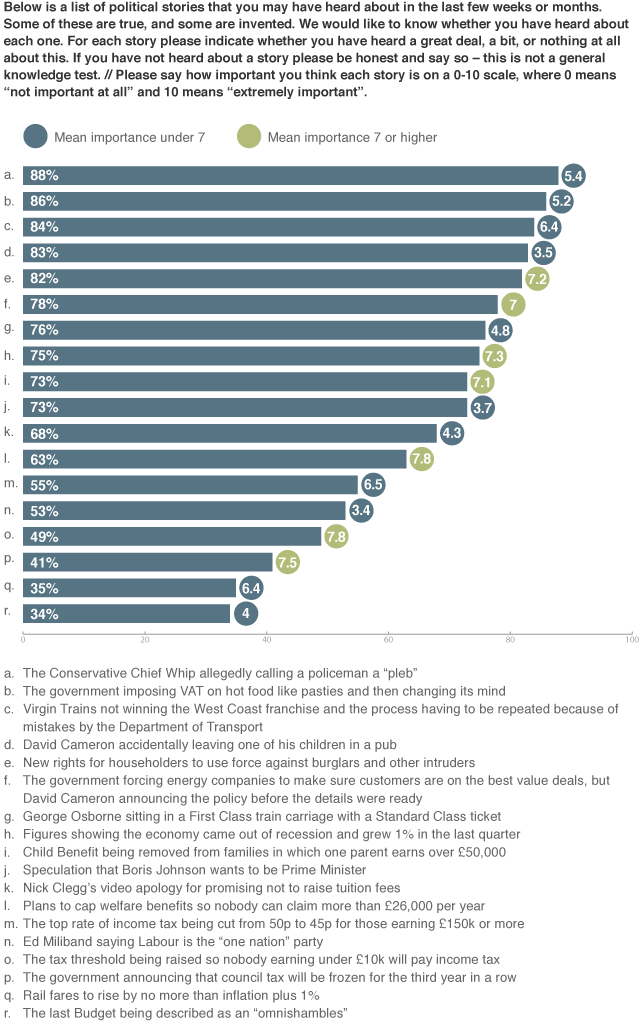

We asked the other half of the sample whether they recalled particular stories (while warning that some false ones had been added to the list, to reduce the risk of people claiming to know more than they did). Again, “plebgate” was top, with 88% saying they had heard about the story, including 70% who said they had heard a great deal. In this question, though, we also asked people to rate the importance of the story in question. Strikingly, the two stories with the highest importance ratings (the benefit cap and raising the tax threshold) came well down the league table for recall. The unfortunate matter of the Chief Whip and the policeman rated eleventh for importance out of eighteen stories tested.

Of the stories we prompted for, the most widely recalled were “plebgate”, the pasty tax, the Virgin Trains West Coast franchise debacle, David Cameron accidentally leaving one of his children in a pub, and new rights for householders to tackle intruders. This last was the only one to number among those regarded as most important – the others being raising the tax threshold, Child Benefit changes, and the council tax freeze.

Overall, men were more likely to recall news items, whether spontaneously or prompted, than women. Older people were more likely to do so than younger respondents (who were also less likely than others to say that any given story sounded important). Liberal Democrat voters were the most likely of all to have noticed particular stories.

Whatever the apparent disparity between what people notice and what they think matters, it would be a mistake to assume that the stories people regard as unimportant have no impact on them politically. The findings, especially of the unprompted question, show that people do register the petty things. They may protest that these incidents are irrelevant, but their view of a government or party can only be shaped by the things they hear about. In an ideal world, the media would pay more attention to the big things and devote less time to the Chancellor’s railway mishaps and other ephemera. But frustratingly, it is true both that most people do not hear a political message until well past the point at which politicians are sick of repeating it, and that they are more likely to notice small things than big speeches or policy announcements. It means the parties need to work all the harder to shift attention to what they want the story to be about.