“Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?” No self-respecting pollster would ask the question that Alex Salmond proposes to put on the ballot paper in his referendum. As Professor Robert Cialdini, the author of Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion told the Today programme last week, the question Mr Salmond wants to use is “loaded and biased”, because it “sends people down a particular cognitive chute designed to locate agreements rather than disagreements”. My latest poll suggests Cialdini is right.

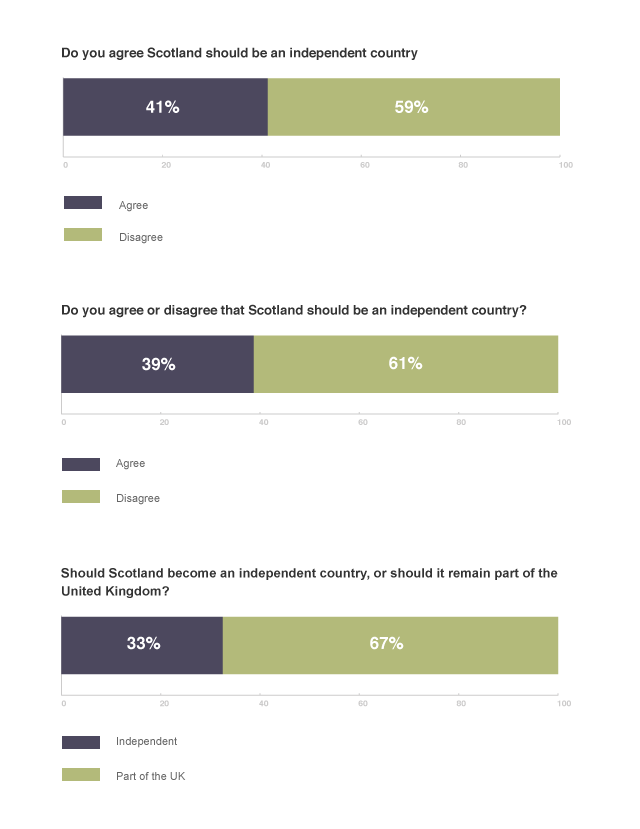

When we asked if they agreed that Scotland should be an independent country, as Mr Salmond intends to do, 41% of Scots answered “yes”, and 59% “no”.

Alongside this, to a separate sample, we asked a question with a subtle but important difference: “Do you agree or disagree that Scotland should be an independent country?” This time, 39% agreed, and 61% disagreed. Not a huge shift (indeed the change in both scores is within the margin of error) but if accurate this represents a four-point difference in the margin between union and independence. It is easy to see how two words – “or disagree” – could, in a close campaign, decide the fate of a nation. Would it be too cynical to suppose this is why Mr Salmond left them out?

Two further things are notable about the Salmond Formulation. First, the use of “be”, rather than “become”. Asking whether Scotland “should become an independent country” emphasises, however faintly, that people would be voting for a significant change. This would probably dampen enthusiasm for independence. (It is often pointed out that the 1975 referendum on the UK’s EEC membership asked whether we should stay, not whether we should join, making “no” seem the risky option). Second, and more striking still, the Salmond Formulation does not mention the United Kingdom – a point made powerfully by Alistair Darling, among others.

Both these omissions were rectified in our final question, in which we asked a third group of Scots: “Should Scotland become an independent country, or should it remain part of the United Kingdom?” Here the shift was decisive. 33% now wanted independence, 8 points lower than under the Salmond Formulation; 67% wanted to stay in the UK.

The fact that results change according to how you ask a question is not startling news. What is clear, though, is that the SNP have chosen the version of the question most likely to deliver the answer that would most please them.

Mr Salmond is not a pollster, he is a politician. Though he is committed to asking the Scottish people whether they want independence, he is equally determined to get the answer he wants. The question is too important to be asked in such a partisan way.