Last month the UK Independence Party came second in two parliamentary by-elections, in Rotherham and Middlesbrough. This prompted its leader, Nigel Farage, to claim his party was the new third force in British politics. UKIP now regularly pips the Liberal Democrats to third place in national voting intention polls. The rise of UKIP causes a good deal of angst among the bigger parties, particularly the Conservatives. It is not hard to see why: my research finds that 12% of those who voted Tory in 2010 now say they would vote UKIP in an election tomorrow. Half of all those who would consider voting UKIP supported the Conservatives at the last election.

Many have suggested antidotes to the rise of UKIP. These usually flow from assumptions about what the attraction of UKIP actually is. Yet these assumptions are often mistaken.

Download the full report

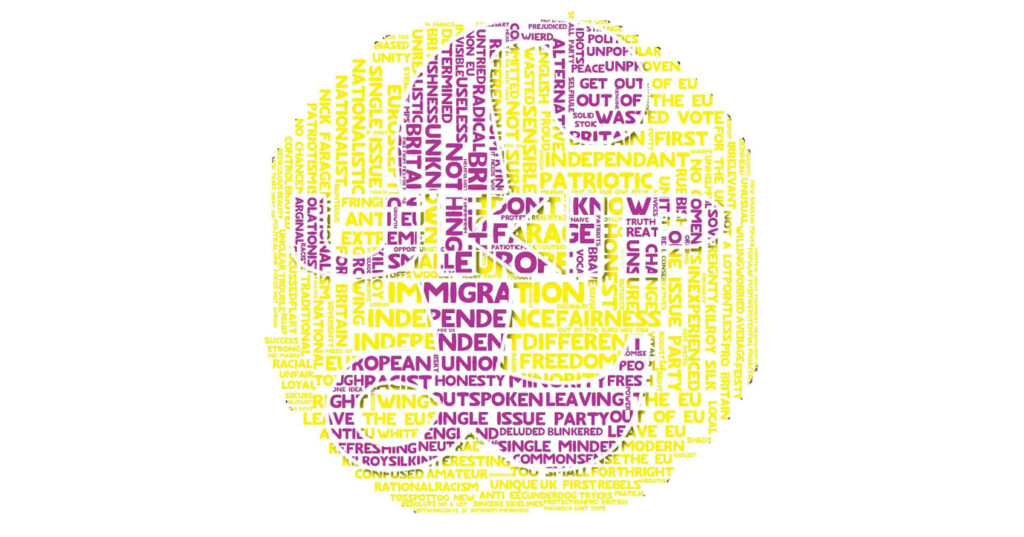

Remedies based on a misunderstanding of what pulls people to the party risk missing the target, or doing more harm than good. This research – the biggest ever survey of UKIP support and potential support, involving a poll of more than 20,000 people and fourteen focus groups with UKIP voters and “considerers” – defines the UKIP temptation.

The single biggest misconception about the UKIP phenomenon is that it is all about policies: that potential UKIP voters are dissatisfied with another party’s policy in a particular area (usually Europe or immigration), prefer UKIP’s policy instead, and would return to their original party if only its original policy changed.

In fact, in the mix of things that attract voters to UKIP, policies are secondary. It is much more to do with outlook. Certainly, those who are attracted to UKIP are more preoccupied than most with immigration, and will occasionally complain about Britain’s contribution to the EU or the international aid budget. But these are often part of a greater dissatisfaction with the way they see things going in Britain: schools, they say, can’t hold nativity plays or harvest festivals any more; you can’t fly a flag of St George any more; you can’t call Christmas Christmas any more; you won’t be promoted in the police force unless you’re from a minority; you can’t wear an England shirt on the bus; you won’t get social housing unless you’re an immigrant; you can’t speak up about these things because you’ll be called a racist; you can’t even smack your children. All of these examples, real and imagined, were mentioned in focus groups by UKIP voters and considerers to make the point that the mainstream political parties are so in thrall to the prevailing culture of political correctness that they have ceased to represent the silent majority.

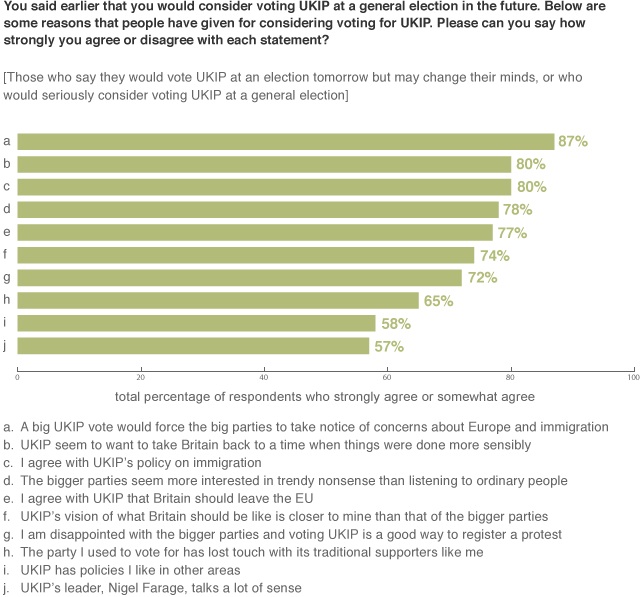

UKIP, for those who are attracted to it, may be the party that wants to leave the EU or toughen immigration policy but its primary attraction is that it will “say things that need to be said but others are scared to say”. Analysis of our poll found the biggest predictor of whether a voter will consider UKIP is that they agree the party is “on the side of people like me”. Agreement that UKIP shares their values and has its heart in the right place are also more important than policy issues in determining whether someone is drawn to the party. The idea that UKIP “seem to want to take Britain back to a time when things were done more sensibly”, and that “the bigger parties seem more interested in trendy nonsense than listening to ordinary people” both elicited stronger agreement among UKIP considerers than the party’s policy that Britain should leave the EU.

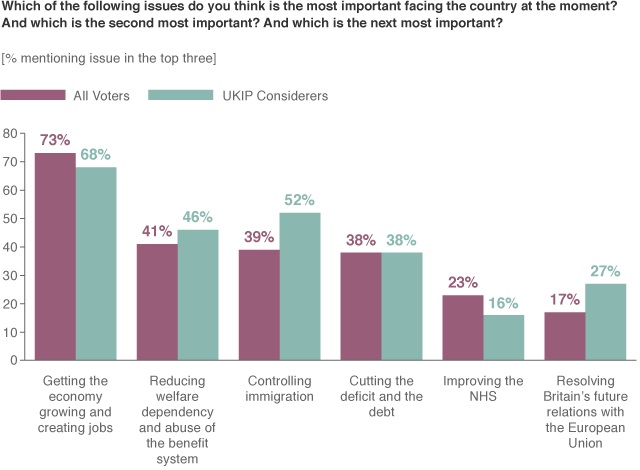

Only just over a quarter of UKIP considerers put resolving Britain’s future relations with the EU among the top three issues facing Britain; only 7% of them say it is the single most important issue. For them, it ranks behind economic growth, welfare, immigration and the deficit. Just over a quarter of them say UKIP are the best party when it comes to defending Britain’s interests in Europe; 42% actually name the Conservatives. Those who have already voted for UKIP in a general election are much more committed to EU withdrawal than those who are thinking of defecting from other parties.

In our research, discussion among UKIP voters and considerers was dominated by what they saw as the twin themes of immigration and welfare much more than by Europe (indeed in one group Europe was mentioned spontaneously only once, when a lady said how well she thought David Cameron had done by putting his foot down over the budget at the recent EU summit). Many complained that migrants from within the EU and outside had changed the character of their local area beyond recognition. Recession and austerity brought their complaints into sharper focus and heightened their resentment: they themselves worked long hours for stagnant incomes as the cost of living rose, and had in many cases lost out on tax credits or other benefits; immigrants, meanwhile, seemed to them to be entitled to extra financial help, and priority access to public services, and to be depressing wages and importing an alien culture.

These voters think Britain is changing for the worse. They are pessimistic, even fearful, and they want someone and something to blame. They do not think mainstream politicians are willing or able to keep their promises or change things for the better. UKIP, with its single unifying theory of what is wrong and how to put it right, has obvious attractions for them.

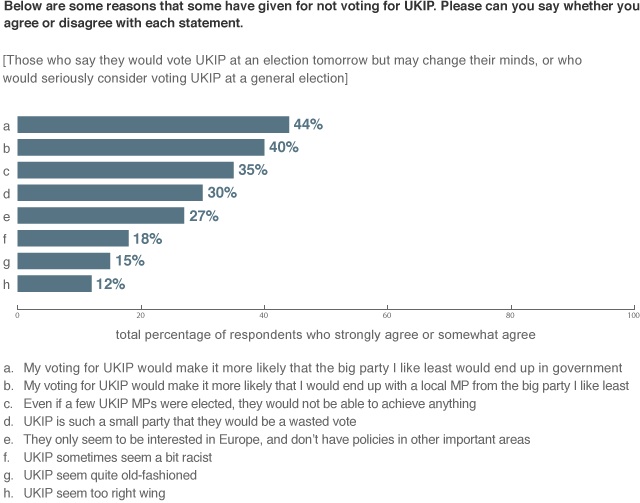

Many of those who are drawn to voting UKIP recognise the wilful simplicity of the party’s rhetoric: that we could cut taxes, increase defence spending and balance the budget all at once, and cut crime and improve access to the NHS, if only we left EU and clamped down on immigration. For some of them, this simplicity does not matter. They have effectively disengaged from the hard choices inherent in the democratic process, though they still want formally to take part in it. They say that being remote from power means UKIP can say what they really think, though there is a tacit acknowledgment that it also means they can say what they like and never be called on it. Not only does it not matter that UKIP will not get the chance to deliver its policies, that is part of the attraction: their diagnosis cannot be gainsaid. Now that the Liberal Democrats have been exposed – and have exposed their supporters – to the realities of government, UKIP is the only party (at least this side of the Greens) by which nobody can feel let down.

Most UKIP considerers are still engaged enough to be open to persuasion at a general election, but European elections are a different matter. The Conservative Party should prepare itself for the likelihood that UKIP will do very well indeed in the European Parliament elections in 2014, whatever David Cameron says in the meantime about Europe or anything else. Most importantly, it should not panic if this happens. Voters readily distinguish between elections that matter and those that matter less. In our research people compared European elections to the Eurovision Song Contest; some cheerfully said that voting UKIP in these elections was just a way to “give Europe a slap”. A strong UKIP performance in eighteen months’ time – even if they were to win more seats than any other party – need not mean electoral doom for the Tories the following year.

An in-out referendum on the EU is not the answer to the question of how to win back potential UKIP defectors to the Tories. It may be the answer to a different question, but not to this one. There are many good reasons for Britain to reconsider its relationship with Europe. But if the Prime Minister decides to hold a referendum, it should not be with the aim of scuppering UKIP. For one thing, it would probably fail – Europe is only a small part of what attracts most people to the party. The wider reasons, of values and outlook and general dissatisfaction with the direction of things, would still apply. Europe is much more of a preoccupation for the hard core of UKIP than for the party’s potential converts. A referendum would be unlikely to win back the irreconcilables, and would fail to address the concerns of the persuadables. Meanwhile, the voters the Tories need to attract from elsewhere would see the Conservative Party’s agenda once again dominated by Europe – a subject which barely registers on their list of concerns.

UKIP considerers who are concerned about immigration – which is to say, most of them – do not believe the government is keeping its promise to tackle the issue. In fact, the government has a better story to tell in this area than they have heard. At the same time, many instinctively approve of the government’s welfare reforms in principle, but feel the first to lose out have too often been deserving but easy cases, while bigger unfairnesses in the system are not tackled. Economic pessimism is also an important part of the mix of opinions that drive people away from the mainstream, and this, too, is within the government’s power to address.

Where voters are driven towards UKIP by a deeper unease simply with the way life has changed in modern Britain, there are clearly limits to how far the Conservatives want to share their view. The Tories said once before that Britain was becoming a foreign land; we told those who agreed that if they came with us we would give them back their country. As we found, there is no future in that kind of approach for a party that aspires to govern, or appeal beyond a disgruntled minority. We cannot “dog whistle” to them that we share their view, in the hope that nobody else will notice.

Those who are open to persuasion can be won round by leadership from David Cameron (including continuing to develop a muscular approach in Europe), the assurance that we are delivering our promises on immigration, that welfare reform is both firm and fair, and evidence that the right decisions are being made on the economy.

That is not to be complacent. Many people who need to vote Conservative if the party is to remain in office, let alone win a majority, are clearly dissatisfied enough with the Tories’ performance in government to be looking elsewhere. The four tests I set in Project Blueprint for all Conservative activity – that it demonstrates leadership, shows the right priorities, shows we are on the side of the right people, and offers reassurance about our character and motives – apply as much to potential UKIP voters as to the other parts of the Conservative voting coalition we have to attract and keep.

But ultimately, the battle between UKIP and the Conservatives is less about ideas, policies, or even values. It is a battle between the party of easy answers and the party of tough decisions. Those who want nothing but the former will not be persuaded. Those who want the latter need to be reassured that those decisions are right, and that they are bearing fruit.