David Cameron has recently confirmed his intention to legislate for gay marriage before the next election. The debate has continued over the summer break: last weekend the Coalition for Marriage published a poll showing that the plans could cost the Conservatives support among churchgoers; earlier this week Boris Johnson released a video restating his support for the idea. The intervention of the Mayor shows that the debate is not just one of left versus right within the Conservative Party, if indeed that delineation still applies. More importantly, it is a reminder that dropping the proposals in order to mollify one group of voters – as opponents of gay marriage advise – would have repercussions of its own. In my recent polling I have tried to look objectively at voters’ reaction to the idea.

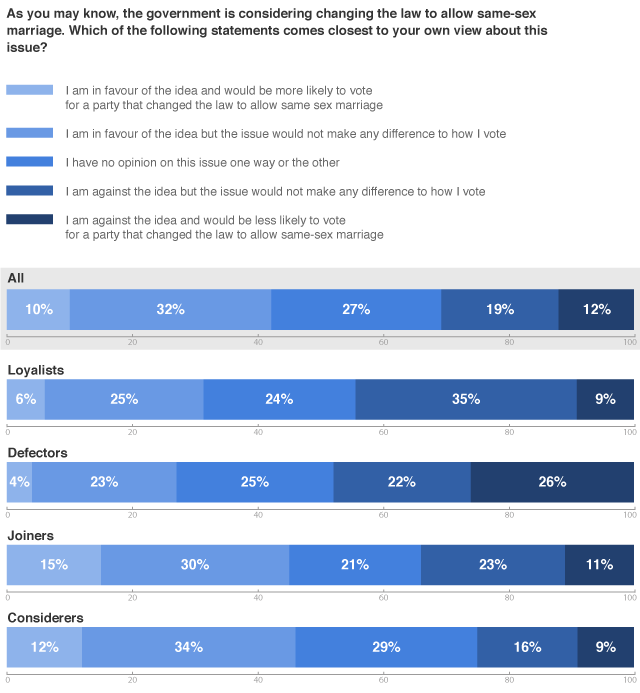

I found that despite the impassioned arguments of its advocates and opponents, relatively few voters have a strong view about gay marriage or say it would definitely influence their vote. Overall, more were in favour of the idea (42%) than against it (31%). A quarter of those in favour (10% of all voters) said they would be more likely to vote for a party that changed the law to allow same-sex marriage; three quarters (one third of all voters) said they were in favour of the idea but the issue would not make any difference to how they voted.

Of the smaller number who were against gay marriage, most said the issue would not make any difference to their vote, but just over a third of them (12% of all voters) said they would be less likely to vote for a party that introduced it.

More than a quarter (27%) said they had “no opinion on this issue one way or the other”.

This was reflected in qualitative research. Most people had not heard the issue was on the agenda. When it was raised, they tended to be very relaxed about the idea. By far the most common reaction was that if gay people wanted to get married, by all means let them get on with it; if the church did not want to take part, it should not (and need not) be compelled to. Many also felt that such a change was part of the development of a more equal and accepting society. Some admitted to being uncomfortable with the idea (“I still can’t get my head around it”), but they did not suggest that marriage in general, or their own marriage in particular, would be undermined or devalued by the proposed change.

In political terms, voters’ one important caveat to all this was that it should not occupy too much of the government’s attention. It sounded to people like the sort of thing that could be proposed, debated and voted on in an afternoon, leaving parliament free to return to more pressing priorities. Many would lose patience quite quickly if, like constitutional reform, the question seemed to become a distraction from things that mattered to them more.

The poll revealed some notable differences of opinion between different kinds of people. Perhaps not surprisingly, the biggest variations within the population as a whole were related to age. A majority of those aged under 45 were in favour of introducing same-sex marriage, and 25% of 18-24 year-olds said they would be more likely to vote for a party that allowed it. Only just over a fifth of people aged 65 or over supported the idea, and they were nearly twice as likely as the population as a whole to say they would be less likely to support a party that introduced gay marriage.

More intriguing from a political point of view are the variations between the different types of voter I identified a few weeks ago in Project Blueprint. Conservative Loyalists – those who voted Tory in 2010 and would do so again tomorrow – were more likely to oppose the idea of gay marriage (44%) than to support it (31%). Defectors, who voted Tory in 2010 but say they would not do so tomorrow, opposed gay marriage in fairly similar proportions (48% to 27%); the difference was that they were nearly three times as likely as Loyalists to say they would be less likely to vote for a party that allowed it (26%, compared to 9% of Loyalists).

Meanwhile Joiners (who did not vote Conservative in 2010 but would do so now) and Considerers (who did not and would not tomorrow, but would consider doing so in the future) were more likely to favour gay marriage than the population as a whole, and more likely to say they felt strongly about it. 15% of Joiners said they were in favour of the idea and would be more likely to vote for a party that allowed it – half as many again as among voters generally, and three times as many among as Loyalists and Defectors.

In an echo of the more general strategic conundrum I presented in Project Blueprint, this demonstrates the potential cost of putting Defectors at the top of our priority list. If, as some argue, the Prime Minister were to drop his plans to introduce gay marriage he would be unlikely to win many back on the strength of it. People who oppose gay marriage would remember that he was in favour of it before the going got tough. Those who support it would see that he abandoned the idea in the face of a determined minority. Those who don’t much care either way would notice another flip-flop. In political terms, ditching gay marriage would probably be more likely to put off Joiners and Considerers – whom we need if we are to win a majority – than it would to win back Defectors.

It is notoriously difficult in polling to work out the electoral impact of a given policy with any certainty. People vote for a host of different reasons; their choice must take into account everything they know or feel, good and bad, about a party or candidate. They are therefore very unreliable when it comes to assessing to what extent one issue, taken in isolation, will affect their decision. Some Conservatives will no doubt find themselves unable to vote Tory this time if the plans go through – but it is also clear that the traffic would not all be one way.

I understand that an issue like this cannot, and perhaps should not, be reduced to an electoral equation of whether the Party is ahead on a net sum basis. For many on both sides of the debate, it is a question that transcends politics, one of principle on which public opinion is effectively immaterial. Of course MPs who feel this should vote with their consciences. But those who argue that gay marriage is a clear-cut net vote loser – and that abandoning the idea would help the Conservatives towards a majority – should examine the evidence more carefully.