Following David Cameron’s first anniversary as Prime Minister, comment has been dominated by the state of the coalition government. To me, this is intriguing but secondary. What matters to me is not so much the coalition between the parties, but how to create the coalition of voters who will elect a Conservative government with an overall majority. The purpose of Project Blueprint is to help work out how to build this election-winning Conservative voting coalition.

My research has looked in detail at those who voted Conservative in 2010, and those who thought about doing so but decided not to (the group from whom most new supporters will have to be drawn). In addition, this polling has helped define and quantify the elements of the potential Conservative voting coalition, and to isolate the issues or perceptions that drive the voting intentions of different voter groups. I wanted to work out what they have in common, where they differ, and whether attracting one element of the potential coalition would necessarily repel another. Some may think the government is a bit too Tory, and others think it is not Tory enough: can both be persuaded to vote for David Cameron in four years’ time?

Methodology

Conservative voters: An online poll of 1,502 people who voted Conservative at the 2010 general election was conducted between 25 February and 3 March 2011. Eight focus groups of people who voted Conservative at the 2010 general election were held in Elmet, Hastings, Brentford and Leamington between 2 and 15 March 2011. Separate groups of men and women were held at each venue.

‘Considerers’: An online poll of 2,000 people who considered voting Conservative at the 2010 election but decided not to was conducted between 25 February and 3 March 2011. Eight focus groups of people who had considered voting Conservative in 2010 but decided not to were held in Hammersmith, Southampton, Dudley and Bolton between 16 and 28 February 2011. Separate groups of men and women were held at each venue.

General public: An online poll of 10,238 adults was conducted between 10 December 2010 and 5 January 2011.

Conservative Party members: A poll of 401 members of the Conservative Party was conducted between 4 and 9 March 2011. 300 interviews were conducted by telephone and 101 online.

Summary of key points

Click here to download the full report

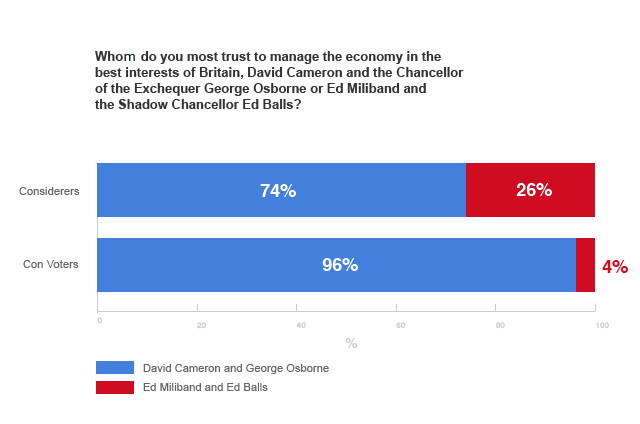

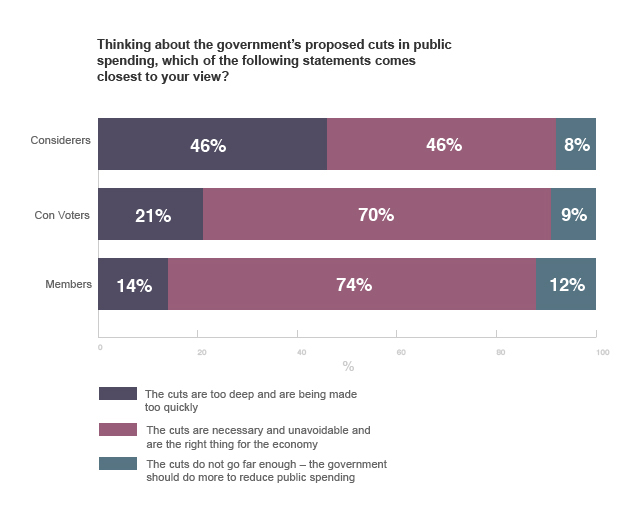

Those who voted Conservative in 2010 were largely satisfied with the government’s performance. Nearly nine out of ten thought the right decisions were being made on the economy, and three quarters supported the cuts. They were more likely to say their view of the party had improved since the election than to say it was worse.

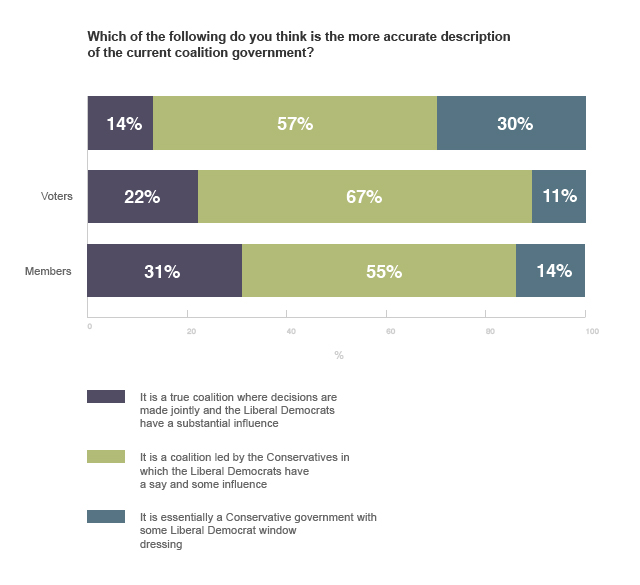

The Conservative voters most likely to defect are not longstanding supporters, but those who voted for the party for the first time in 2010. The main motivation for these first-time Tories was to get rid of Labour, so their view of the Conservatives was not necessarily very positive to start with. They were more likely than Conservative voters as a whole to say the coalition was doing worse than they expected, and to think the coalition was essentially a Conservative government with some Liberal Democrat window dressing. They were twice as likely as Tories generally to say the cuts were too deep and too quick. The proportion wanting to see an outright Conservative majority at the next election was lower than for Conservatives as a whole. Only just over half said they would vote for the party in 2015 (though a very high proportion said they didn’t know), well below the level for Conservative voters overall.

Women were consistently and significantly less enthusiastic about the Conservative Party and the government’s performance, and more concerned about the cuts, than men.

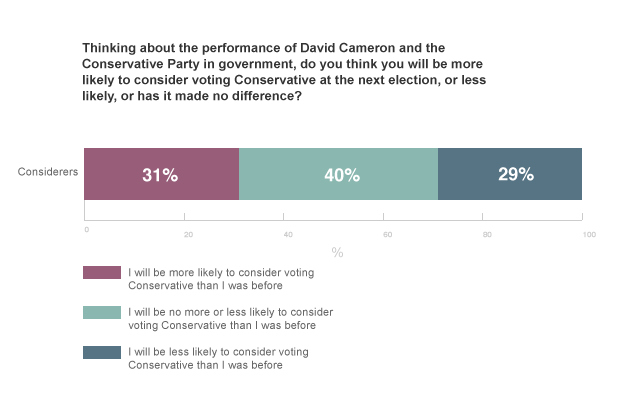

Considerers – those who thought about voting Conservative in 2010 but decided not to – were less enthusiastic about the government and its decisions. The biggest barrier, which was not overcome by election day and remains in place for many of them, is the perception that the Conservative Party is for the rich, not people like them.

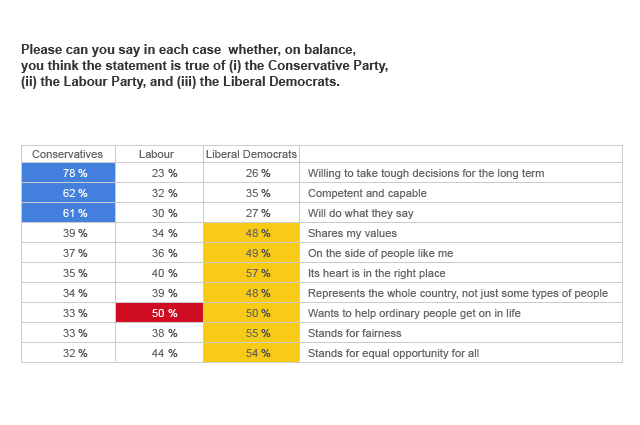

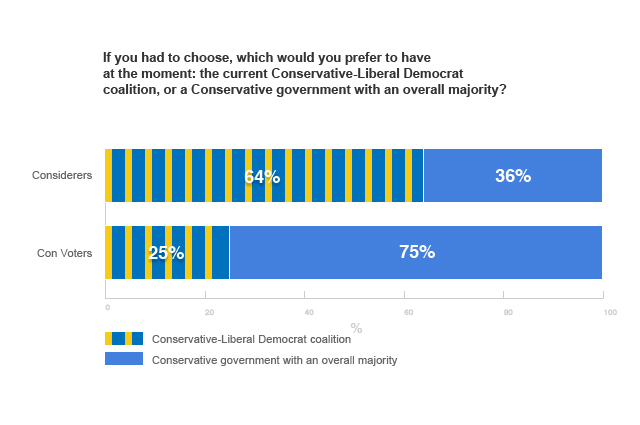

Considerers nevertheless rated the Conservatives well ahead of the other parties on hard measures like being willing to take tough decisions for the long term, being competent and capable, and doing what they say they will do – though behind on softer measures like fairness. They were as likely to say their view of the Conservatives had changed for the better (most often because they were impressed with David Cameron and thought the party was doing what it promised) as to say it had changed for the worse. Unlike Conservative voters, though, most considerers said they would much prefer the present coalition to a Conservative government with an overall majority.

Welfare reform is a striking success for the Conservatives. People grasped and strongly supported specific elements of the government’s plans, and recognised that they were being implemented. On immigration, though many people supported Conservative plans before the election, it was much less clear to them what had actually been done. Crime represents a coalition-building opportunity that is being missed. Most had expected a Conservative-led government to be tougher on crime, but when asked what was being done on the issue most could only think of police cuts, with some adding that the government seemed to want to send fewer criminals to prison. Many participants thought the NHS was subject to cuts, even though the government says its budget is being maintained and increased. Most people were sceptical of the proposed reforms. Nobody seemed to know why the reforms were needed and how, even in theory, they were supposed to improve things for patients.

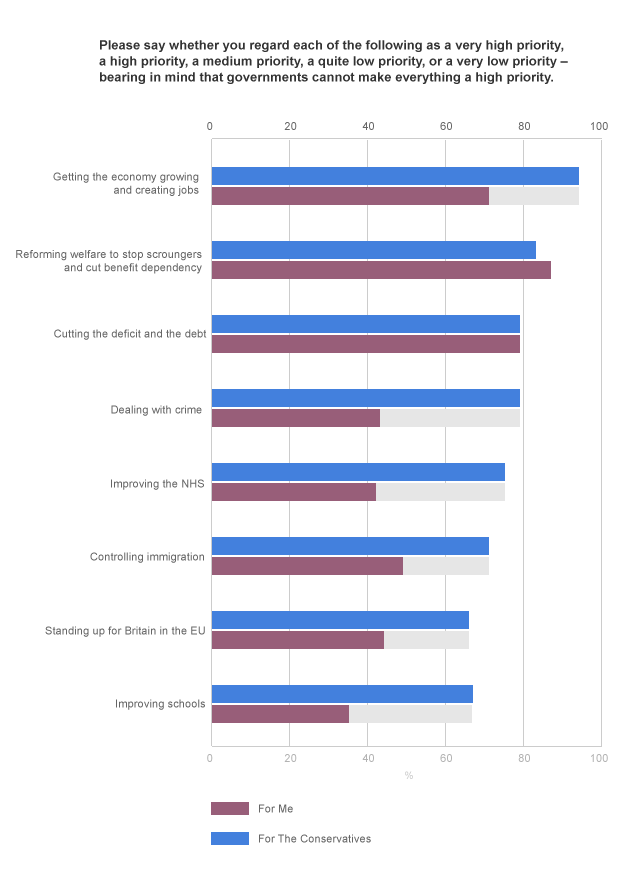

Although voters recognised that cutting the deficit was an important priority, the more important factor for them was getting the economy growing and creating jobs. People thought the government seemed to see everything – growth, welfare reform, changes to sentencing policy, immigration control – as a means to the end of deficit reduction. They did not see the end to which deficit reduction is the means, or the benefits the cuts would bring in years to come.

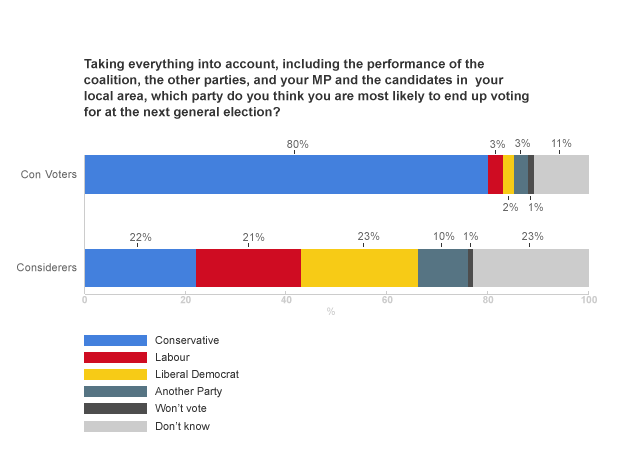

Headline voting intention figures in the polls obscure the fact that the Conservative Party has lost close to one in eight of its voters from 2010. However, these have been replaced by a section of the electorate which did not vote Tory. By far the most important feature of this group was the belief that the Conservatives had the best approach to the economy; this was followed by high approval ratings for the Prime Minister. Just under one in four Labour voters who thought the Conservatives had the best approach to the economy said they would vote Tory tomorrow (compared to three in a thousand of those who did not think this).

For half of defectors, the most important repelling factor was that they did not think the Conservatives had the best approach to the economy; the great majority also felt the Tories were not the best party on the NHS. The other evidence suggests these included a high proportion of first-time Conservatives who were worried about the cuts and had been wary of trusting the party on public services.

The segmentation analysis, which can be studied in detail in the full report, suggests the things that will build and maintain the Conservative voting coalition are the economy, David Cameron, welfare, crime, the NHS and a demonstration that the Conservative Party shares people’s values. These are mainstream concerns that can expand the Conservative voting coalition and delight longstanding Tories at the same time. In other words, attracting new voters need not alienate existing supporters.

Click here to read my commentary on the research, published in the Sunday Telegraph.