Donald Trump is not an apparition. Though to some of his critics he is the stuff of nightmares, he’s real, and he’s back. His opponents can no longer take refuge in the idea that he somehow fluked his way into office thanks to bigotry, ignorance, a cult of personality or the quirks of the electoral college: he won the popular vote and all seven swing states. Having lived through a term of Trump and the four years that followed, Americans sent him back to the White House with their eyes wide open.

For all his supposed divisiveness, Trump put together a remarkable voting alliance that would have seemed unthinkable for a Republican only a few elections ago. He performed better among women and minorities than in 2016 or 2020, winning nearly four in ten non-white men – not to mention nearly half of immigrants, Gen Z, Millennials and voters in union households. He did so by appealing to a sense of national purpose, security, the promise of more people sharing in the country’s prosperity, and a government that reflects their values, not that of an aloof elite.

All this feels strangely familiar. Such parallels are never exact, but there are echoes of 2019 when Boris Johnson stormed to victory promising to break the Brexit deadlock, take back control and “unleash Britain’s potential”. Levelling up would bring opportunity and prosperity to parts of the UK neglected by a complacent establishment. Johnson brought to the Conservative camp all sorts of people who would never have expected to be there, in places which had never voted Tory before, expanding and transforming the Conservative coalition.

At least temporarily. As we all know, the story of the 2019 parliament ends less happily for the victors than it began. It can also serve as a cautionary tale for the incoming Trump administration, and any Republicans relishing the prospect of a long hegemony. The Tories found to their cost that a diverse coalition of support brings its own internal tensions and competing interests. Not only that, a thumping victory brings high expectations, especially if they are based on extravagant but not very specific promises.

Unable to settle on any kind of political direction or to deliver basic competence (let alone to level up or unleash anything worth having), the Tories squandered this realignment of British politics instead of consolidating it. So far, the Trump team is showing a sense of urgency and purpose which was lacking for most of the post-2019 Tory era in Britain. In my pre-election research in the US, voters often told us they were hiring Trump to do a job. That is why they picked him despite what they often saw as his personal flaws.

But it also means they expect him to deliver, and they’ve handed him Republican majorities in the House and the Senate to help. Different parts of the Trump coalition – comprising the new multi-ethnic working class as well as more traditional GOP voters – will not always see eye to eye. Moreover, some of Trump’s promises could trip each other over. Can he follow through on his threat to change the terms of international trade by imposing hefty tariffs while keeping down prices for hard-pressed consumers?

Hopes are high, and the president-elect has not exactly discouraged them. Americans want lower prices, more jobs, higher wages, secure borders, less immigration, fewer wars, better government and lower taxes. Many recall the first Trump term as a time of relative abundance and ease, when Putin was in his box and the southern border was fairly secure. How quickly can Trump take America back to those days – or, even more demanding, something resembling people’s rosy memory of them? A Democrat resurgence at the 2026 midterms looks unlikely now… just as a huge Labour majority did in the wake of their kicking five years ago this week.

If the Republicans would benefit from reflecting on what followed their allies’ recent triumphs, there is also a warning for the left. Could the newly elected Trump be the ghost of Labour’s future?

In 2020, Joe Biden was elected as a safe pair of hands to put an end to a chaotic administration millions of Americans couldn’t wait to see the back of (their newly fond memories of it notwithstanding). He was selected by his party as the least frightening and most electable prominent Democrat, and he campaigned as a moderate. But as I repeatedly heard from voters across the US, he didn’t govern as one. Huge federal spending helped fuel the inflation that was voters’ biggest complaint, and the relaxation of border controls led to a quadrupling in the number of illegal migrants. Foreign entanglements multiplied. Climate policy took precedence over energy affordability. The cultural values of the Democrats – whether over trans issues, boys in girls’ sports, a preoccupation with race or the pious policing of language in the name of diversity and inclusion – came to feel ever more at odds with those of the country at large.

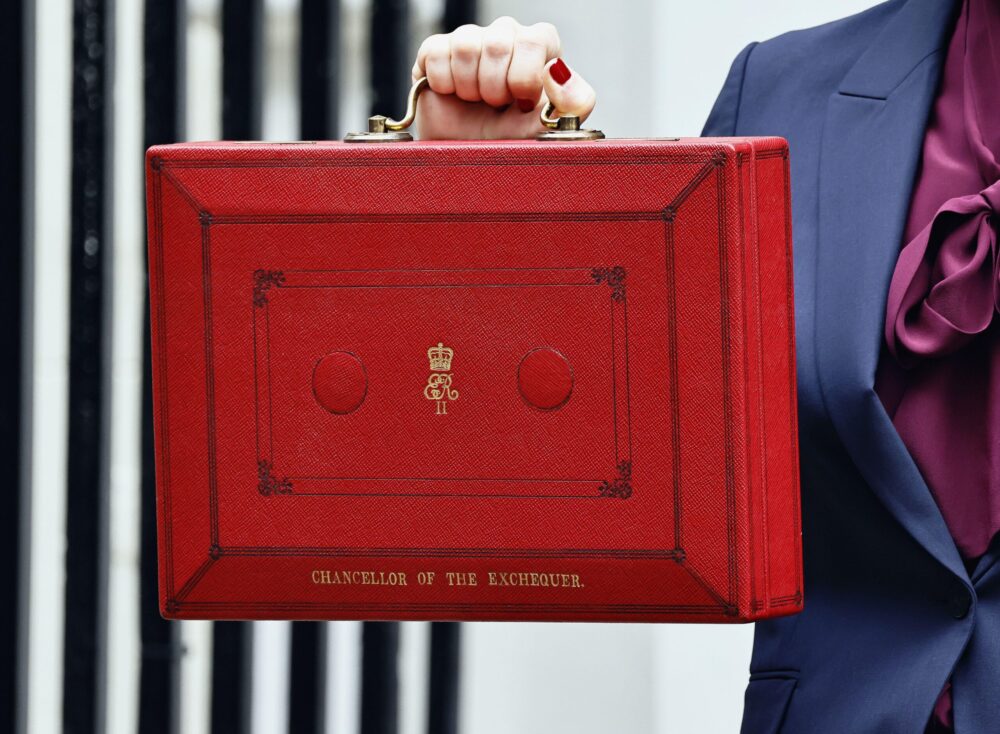

If that doesn’t ring bells in Downing Street, it should. In the five months since the voters heaved the Tories out of office, Labour have governed as though their support in the country matched their majority in parliament. Elected to bring some calm, competence and stability back to British public life, Keir Starmer has made big, unpopular changes – scrapping the winter fuel allowance, subjecting family farms to inheritance tax – which never appeared in his manifesto.

The fact that Starmer has felt the need to relaunch his government after so short a time hardly augurs well, but nor does the conflict between Labour’s missions on the one hand and their actions on the other. Will they “kickstart economic growth” and “break down the barriers to opportunity” by raising taxes, imposing more regulations and making it more expensive to employ people? Will they ensure “safer streets” by releasing prisoners early and continuing to allow the police to waste their time on non-crime hate incidents? Will they “build an NHS fit for the future” by agreeing generous public sector pay deals with no obligation to improve productivity? Even if they succeed in making Britain a “green energy superpower”, is not affordable, reliable energy not more important to voters than the rush to net zero? And those are just the things Labour say they want to tackle. Immigration, legal or otherwise, is consistently among voters’ top priorities, but merits no mention in Starmer’s “plan for change”.

Like Biden, Starmer won mostly because of what he wasn’t. Like Harris, he will find out soon enough what happens when an administration elected by default oversteps its mandate, ignores people’s concerns and leaves voters feeling worse off. In the Dickensian parable, Scrooge heeds the ghost’s warning and changes his ways, averting the fate that awaited him. Can the prime minister do the same?