As well as our usual tracking questions on voting intention, best PM, trust on the economy and preference of government, my 5,000-sample poll this month asked about Labour’s abandoned £28 billion green pledge, what Ofsted rating voters would give the government, whether people feel better or worse off than they did four years ago, whether various things are more likely to happen under the Conservatives or Labour, and how worried – if at all – people are about the idea of a Labour government with Keir Starmer as prime minister. As ever, all the data can be found at LordAshcroftPolls.com

What’s been happening?

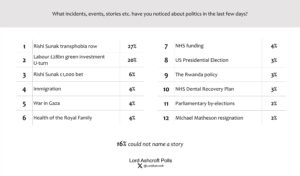

We also asked again what political stories people had noticed in the last few days. Two dominated people’s recollections: Labour’s retreat on its £28bn green investment plan, and the controversy over Rishi Sunak criticising Keir Starmer’s position on defining a woman as the mother of murdered teenager Brianna Ghey attended PMQs. Rishi Sunak’s £1000 bet that a flight to Rwanda would take place as part of the government’s asylum policy before the election was a distant third.

The £28 billion reversal

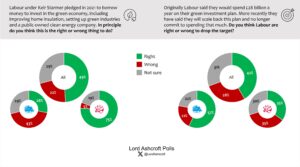

We asked in more detail about the Labour green investment story. Just under half of all voters – including 75% of 2019 Labour voters but fewer than 3 in 10 Tories – said they thought Labour had been right in principle to commit to borrowing money to invest in the green economy, with just 22% saying they were wrong to make such a commitment.

When we asked whether Labour were right to scale back their original commitment of spending £28 billion a year on green investment, a plurality again said the party had been right, and by a fairly similar margin of 42% to 28%. This time, though, the move was approved by a majority (57%) of 2019 Tories, while 2019 Labour voters were evenly divided: 35% in favour of dropping the £28bn target, 35% against, and 30% saying they didn’t know.

Green spaces v. new homes

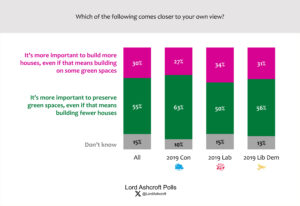

The Conservatives have their own environmental dilemma, highlighted in Michael Gove’s recent remarks on the need to build more houses to meet growing demand, especially among younger voters. The political conundrum is clear – while 3 in 10 agree that it’s “more important to build more houses, even if that means building on some green spaces,” more than half (and 63% of 2019 Conservatives) think it’s “more important to preserve green spaces, even if that means building fewer houses overall.”

Perhaps surprisingly, 18-24 year-olds prefer the second statement by a 14-point margin – though they are the only age group in which the preference for preserving green spaces over housebuilding falls below 50%.

What Ofsted rating would you give the government?

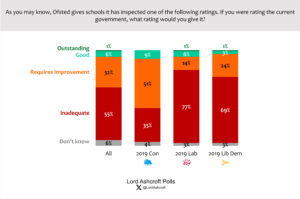

When education secretary Gillian Keegan was in a recent LBD interview what Ofsted rating she would give the government she replied ‘Good’ – putting her firmly in the minority of voters. Only 6% took the same view (though 1 in 100 said they would rate the government ‘Outstanding’); around one third (32%) said ‘Requires Improvement’ and more than half (55%) said ‘Inadequate’.

Only 9% of 2019 Tories rated the government ‘Good’ (none rated it ‘Outstanding’). More than one third (35%) declared it ‘Inadequate’ and more than half (51%) said the government ‘Requires Improvement’.

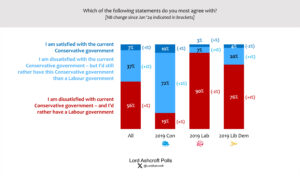

Preference of government

Overall, only 7% of voters (and 10% of 2019 Tories) said they were satisfied with the current government, while a further 37% – and more than 7 in 10 (72%) of those who voted Conservative last time – said they were dissatisfied with the government but would still prefer it to a Labour government. Just over half (56%) of all voters, including nearly 1 in 5 (19%) 2019 Tories, said they were dissatisfied and would rather have a Labour government instead.

More than three quarters (77%) of those currently leaning towards Reform UK said they were dissatisfied with the Conservative government but would prefer it to a Labour one, while 21% of them said they would rather have a Labour government instead. However, among those currently switching from the Conservatives to Reform, 87% said they would prefer the current Tory government and only 13% said they would rather see Labour in office.

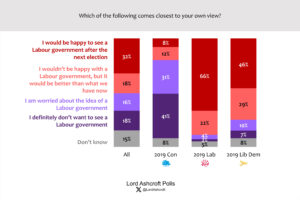

Worried about Labour?

Asking a similar question from a slightly different angle, we found half of voters – including one fifth of 2019 Tories – saying either that they would be happy to see a Labour government after the next election (32%) or that they wouldn’t be happy but it would be better than what we have now (18%).

Nearly 8 in 10 of those currently leaning towards Reform UK said they were either worried about (25%) or definitely did not want to see (54%) a Labour government. Among those switching from the Conservatives, 63% said they definitely did not want Labour in office.

Will anything change?

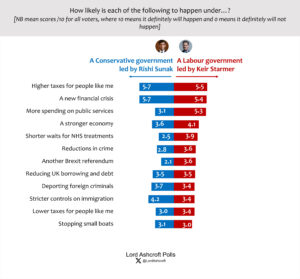

We asked voters how likely they thought various outcomes were on a 10-point under a Conservative government led by Rishi Sunak, and under a Labour government led by Keir Starmer. Only two things were thought more likely to happen than not in both scenarios: ‘higher taxes for people like me’ and ‘a new financial crisis’. The two theoretical governments were also thought equally likely – or unlikely – to bring down the UK’s borrowing and debt.

More spending on public service, a stronger economy, shorter NHS waiting times, reductions in crime, another Brexit referendum and lower taxes ‘for people like me’ were all thought more likely to happen under a Starmer-led Labour government than Sunak and the Tories – though all but higher spending were still considered unlikely.

The Conservatives were thought marginally more likely than Labour to ensure foreign criminals were deported, to impose stricter controls on immigration and to stop the small boats – though even under the Tories voters scored the likelihood of this happening at 3.1 out of 10.

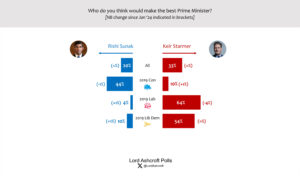

Best prime minister

Asked who would make the better prime minister, voters named Keir Starmer over Rishi Sunak by 33% to 20% – scores unchanged since January – with nearly half (47%) saying ‘don’t know’. Sunak led by 44% to 10% among 2019 Tories, though again nearly half (46%) were unable to choose.

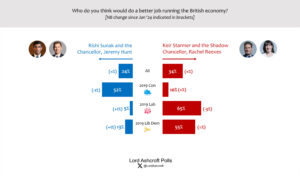

Trust on the economy

Just over one third (34%) said they thought Starmer and shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves would do a better job of running the economy, compared to less than a quarter (24%) who chose Sunak and chancellor Jeremy Hunt. Only just over half (52%) of 2019 Conservatives chose the Tory team, with 39% saying ‘don’t know’.

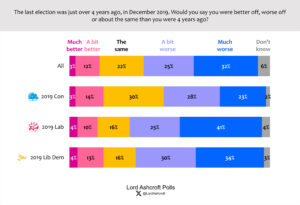

Are you better off than you were 4 years ago?

Only 15% of voters said they were better off than they were at the last election in 2019, while a further 22% said they were about the same. More than half said they were either a bit (25%) or much worse off (32%) than they were four years ago. This included just over half (51%) of those who voted Conservative in 2019, and two thirds of those currently switching from Conservative to Reform UK.

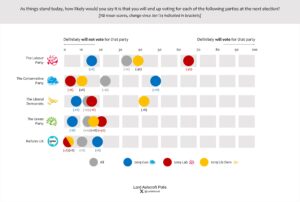

Our voting intention question asks people how likely they are to vote for each party on a 100-point scale, showing the relative intensity of party support among different groups. Taking those who give one party a highest score of 50 or above out of 100, we find Labour on 43% (down a point from January), the Conservatives unchanged on 27%, Reform UK on 10%, and the Greens and Lib Dems tied on 8%. In Scotland, we find Labour and the SNP tied on 30%, with the Tories third on 18%.

Voting intention

Among 2019 Conservatives, the mean likelihood of turning out for the party again is 48/100, compared to Labour voters’ 65/100 probability of sticking with their party. Based on their scores, more than one third (34%) of 2019 Tories don’t know or would not vote. Voters aged 65 or over are the only group in which the Conservatives are ahead, by 43% to 23% over Labour. Among 18-24s, Labour lead with 54%, with the Greens second on 16%, the Conservatives third on 11% and the Lib Dems fourth on 10%.

The political map

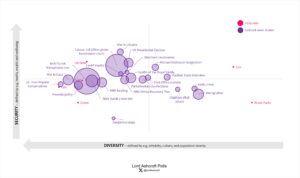

Our political map shows how different issues, attributes, personalities and opinions interact with one another. Each point shows where we are most likely to find people with that characteristic or opinion; the closer the plot points are to each other the more closely related they are. Here we see that the centre of gravity of Conservative support has shifted since 2019 firmly into the more prosperous top-right quadrant, away from the Brexit-supporting less prosperous part of the electorate that constituted an important part of the Tories’ winning coalition. The bottom right is where we also find those most likely to think prioritise reducing immigration, that the Rwanda plan should be implemented as soon as possible, and that things in Britain no longer work properly whoever is in charge.

It is also notable that those who think Labour were right to drop their pledge to spend £28 billion a year on green investment are mostly to be found in the Tory-leaning right hand side of the map, while those who think the party was wrong to drop the pledge are most likely to be found in Labour territory – close to those most inclined to support the principle of green investment in the first place.

We can also see who is most likely to have noticed which political stories in the news. Those most likely to mention the two most-noticed stories of the week – the Labour £28bn policy and the Sunak transphobia row – were to be found squarely in Labour territory on the left-hand side of the map, as was the PM’s £1000 bet with Piers Morgan. Notably, the launch of the PopCons was also more likely to have been noticed among its political opponents than in its target market, where stories about immigration, the Clapham alkali attack and crime were most likely to have registered. Those saying they had noticed no political stories in the news at all were most likely to be in the Brexit-supporting low-diversity, lower-prosperity bottom-right quadrant of the map – where large numbers of disaffected 2019 Conservatives are to be found.