Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine a year ago today. My latest polling reveals how optimism has grown in Ukraine, how Putin has so far largely kept control of the narrative in Russia, and how the British and American public see their country’s role in the conflict.

Allies and aid

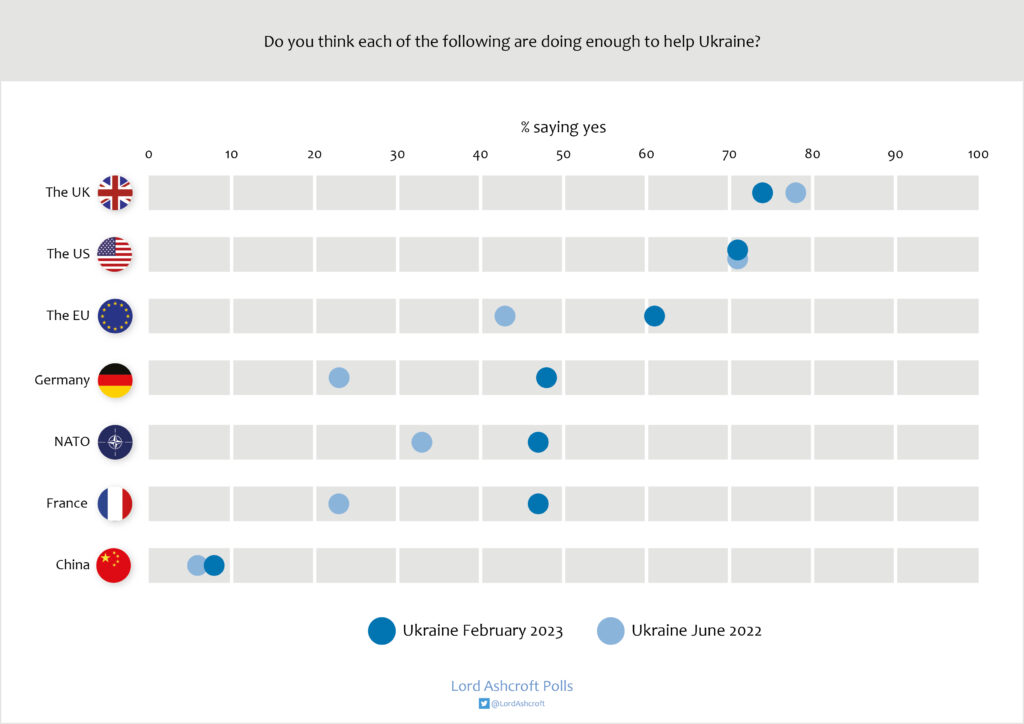

Asked whether various countries and organisations were doing enough to help, nearly three quarters of Ukrainians in our survey said yes for Britain; 71% did so for the US.

Only around half said the same of Germany, France and NATO, though these scores had improved considerably since we asked the same question in June 2022. Welcome as it was, the support could have come sooner: “Other countries did not understand Putin’s level of craziness, or of Russians in general. If we had had tanks in the summer, we could have taken back the territories,” as one Kyiv focus-group participant put it.

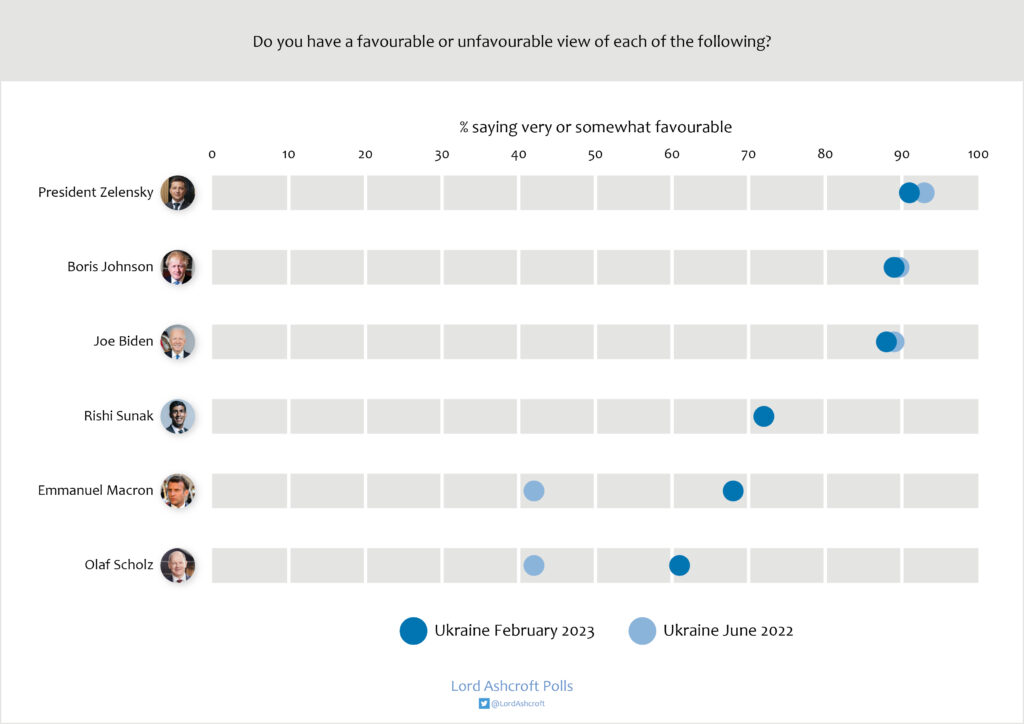

I found Boris Johnson’s personal ratings among Ukrainians (89/100) nearly as high as those of President Zelensky himself (91) – similar to Joe Biden (88) but well ahead of Emmanuel Macron (68) and Olaf Scholz (61). Though less well known, Rishi Sunak (72) had also been noticed as a supporter. “Boris Johnson was specifically for Ukraine, then there was a fight in the UK and this new person appeared,” another recalled. “But he’s shown his support, the Challenger tanks for example.”

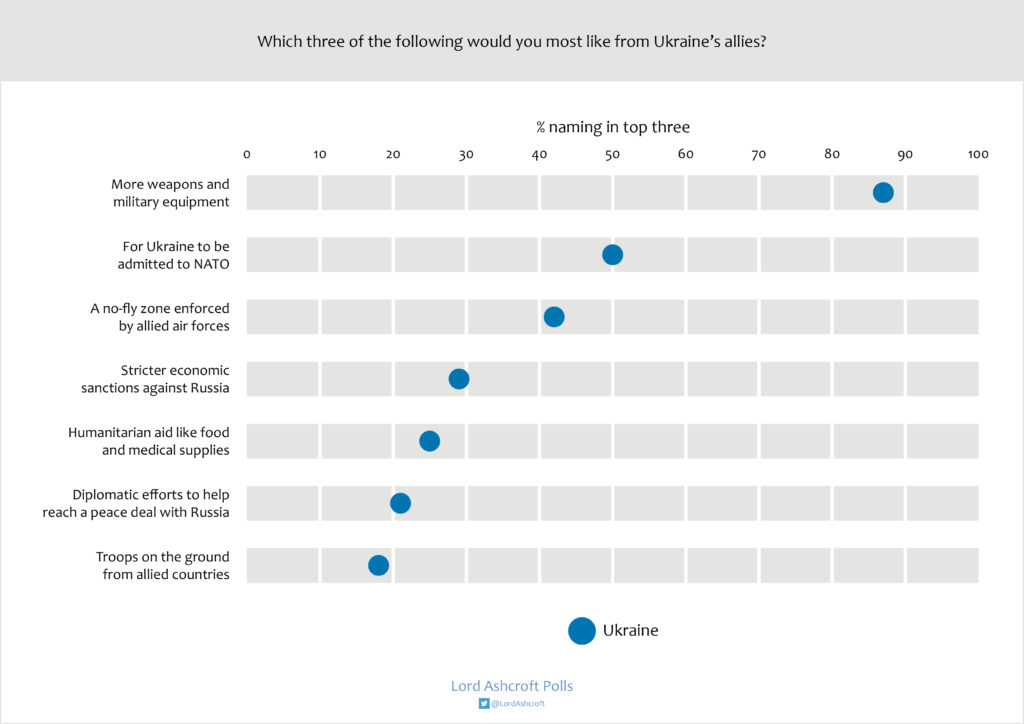

When we asked Ukrainians what three things they would most like to see from their allies, by far the most popular answer was more weapons and military equipment (87%), followed by admission to NATO (50%) and a no-fly zone patrolled by allied air forces (42%). Stricter economic sanctions (29%), humanitarian aid (25%) and diplomatic efforts aimed at a peace deal with Russia (21%) were less of a priority.

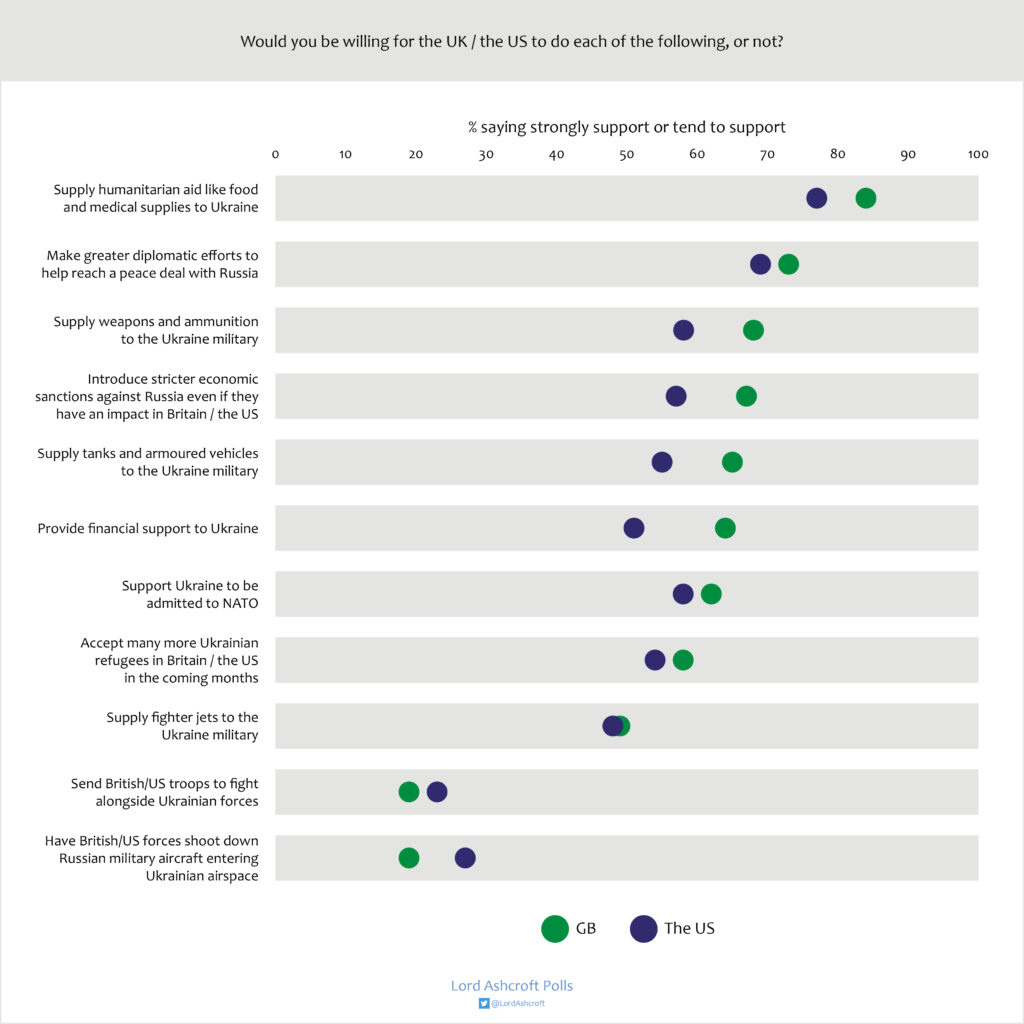

However, when we asked voters in Britain and America what they were prepared to offer, humanitarian aid and diplomatic support were at the top of the menu. In nearly all cases, people in Britain were more willing than their US counterparts: two thirds would supply tanks, armoured vehicles, weapons and ammunition compared to just over half of Americans – though they were similarly willing to provide fighter jets and support Ukrainian membership of NATO.

More striking is the differences of opinion within each country. Three quarters of Democrats said they would be willing to provide tanks and armoured vehicles, compared to fewer than half of Republicans; only 53% of Trump voters would back NATO membership for Ukraine, compared to 76%of Biden voters. In the UK the left-right pattern was reversed: around 8 in 10 2019 Conservatives were willing to supply military equipment, compared to two thirds of Labour voters – though the latter were more willing than Tories to accept many more Ukrainian refugees, by 74% to 53%.

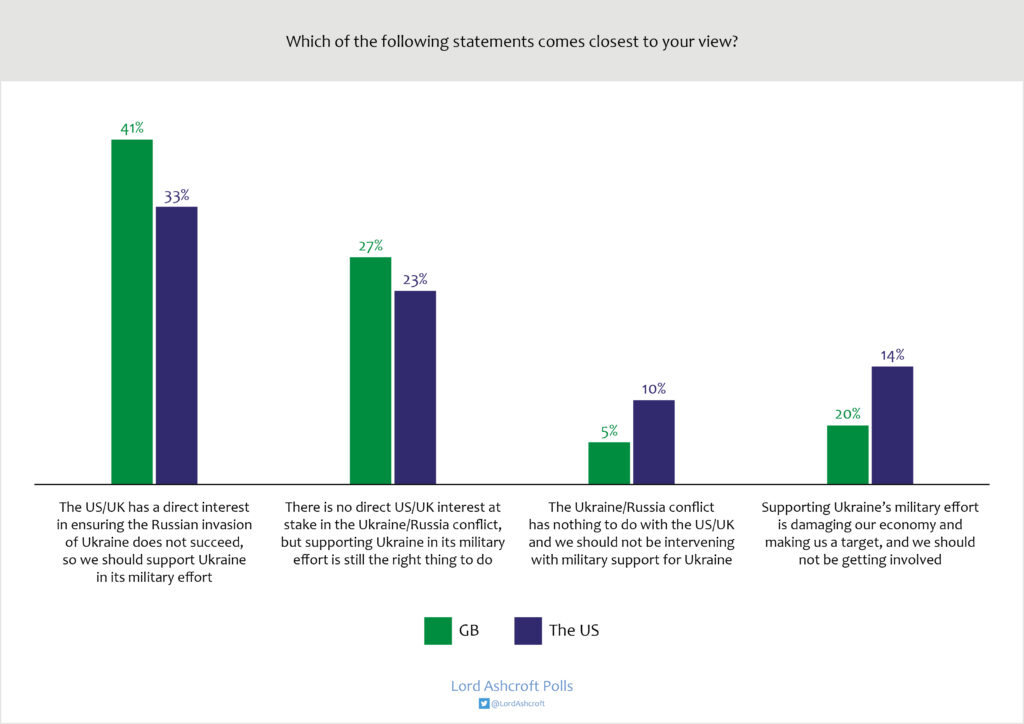

British voters (41%) were more likely than Americans (33%) to think their country has a direct interest in ensuring the Russian invasion does not succeed – or, by a smaller margin (27% to 32%), that giving Ukraine military support is the right thing to do even though there is no direct interest at stake.

One third of Americans said either that the conflict had nothing to do with them or that getting involved was damaging their economy and making them a target, compared to a quarter of people in Britain.

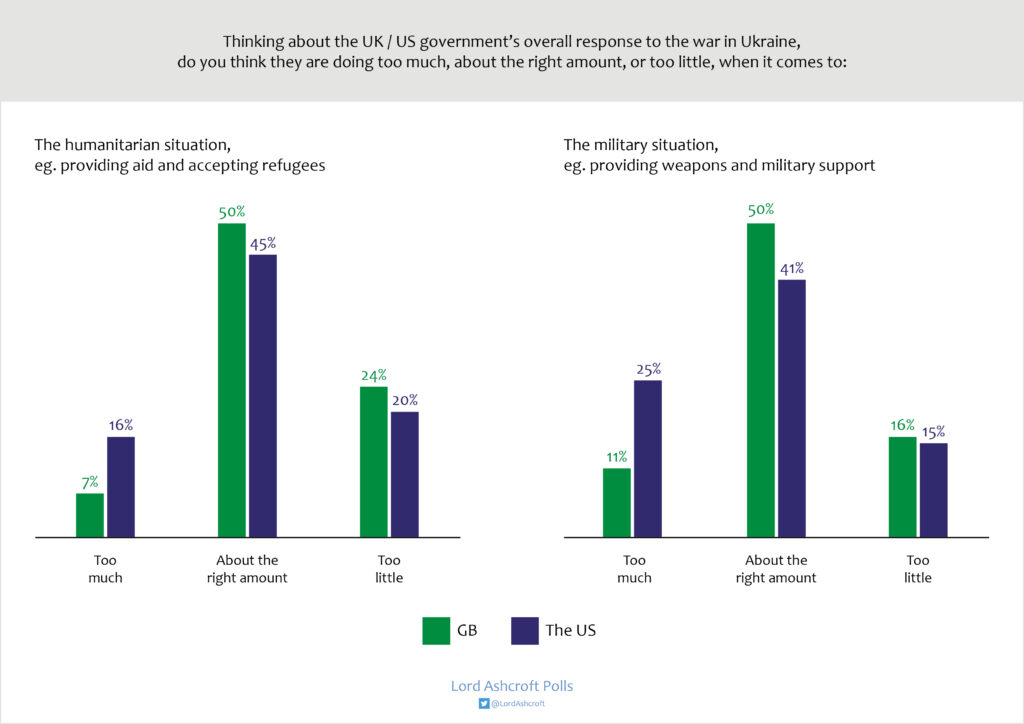

Overall, half of those in Britain said the government was doing about the right amount to support Ukraine, in both military and humanitarian terms, with the remainder more likely to say we were doing too little than too much. In the US, the bulk thought the response was about right, but with a quarter – including 42% of Trump voters – saying America was already giving too much military support.

The Russian view

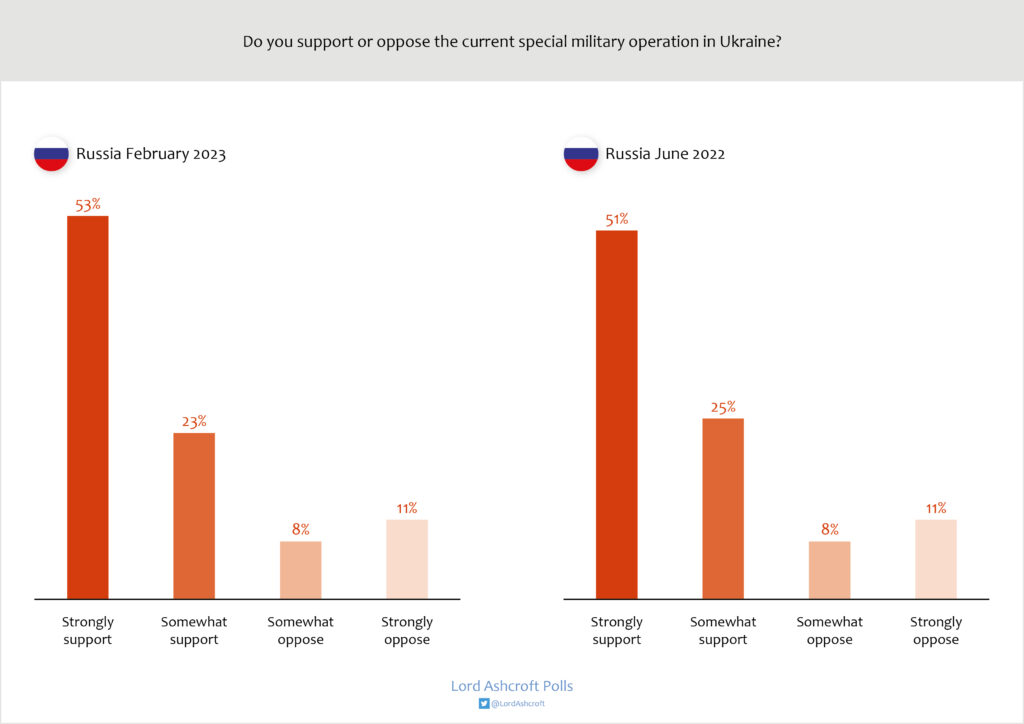

Our survey in Russia, conducted by telephone from a neighbouring state, found overall support for the “special military operation” unchanged since last June, at 76%. Support ranged from 60% among 18–24-year-olds to nearly 9 in 10 among those aged 55 or over. More than 9 in 10 support the annexation of Crimea, and more than 8 in 10 say the same of the territories occupied since the invasion.

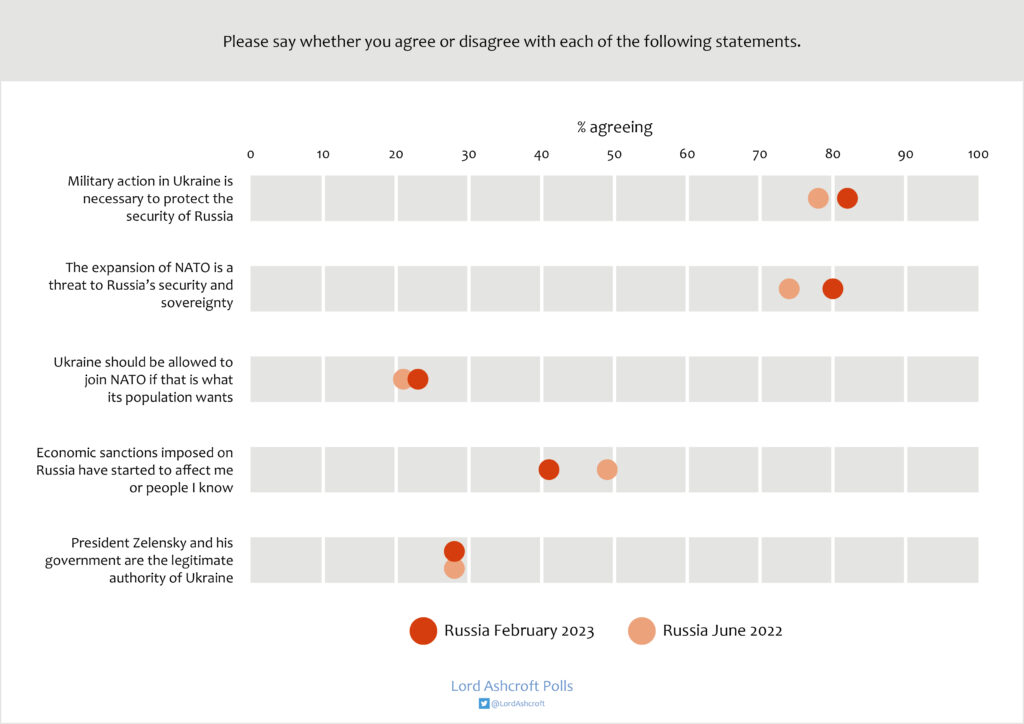

Despite the length of the conflict, the evidence is that Putin’s justification for the invasion has become entrenched: 8 in 10 agree that military action in Ukraine was necessary to protect Russia and that NATO expansion threatened their security and sovereignty – both up a few points since our survey last year. Fewer than 3 in 10 see the Zelensky government as Ukraine’s legitimate authority. Asked who is to blame for the conflict, 81% name the US, 78% name NATO and 72% blame Ukraine; only 41% say Russia has any responsibility.

This was confirmed by our online focus groups with people in the Russian city of Yekaterinburg, 900 miles east of Moscow. “It was denationalisation, to prevent an attack from their side against Russia. We were defending ourselves,” said one. “It was to return Russian territories and stop harassment of the Russian population,” was another explanation.

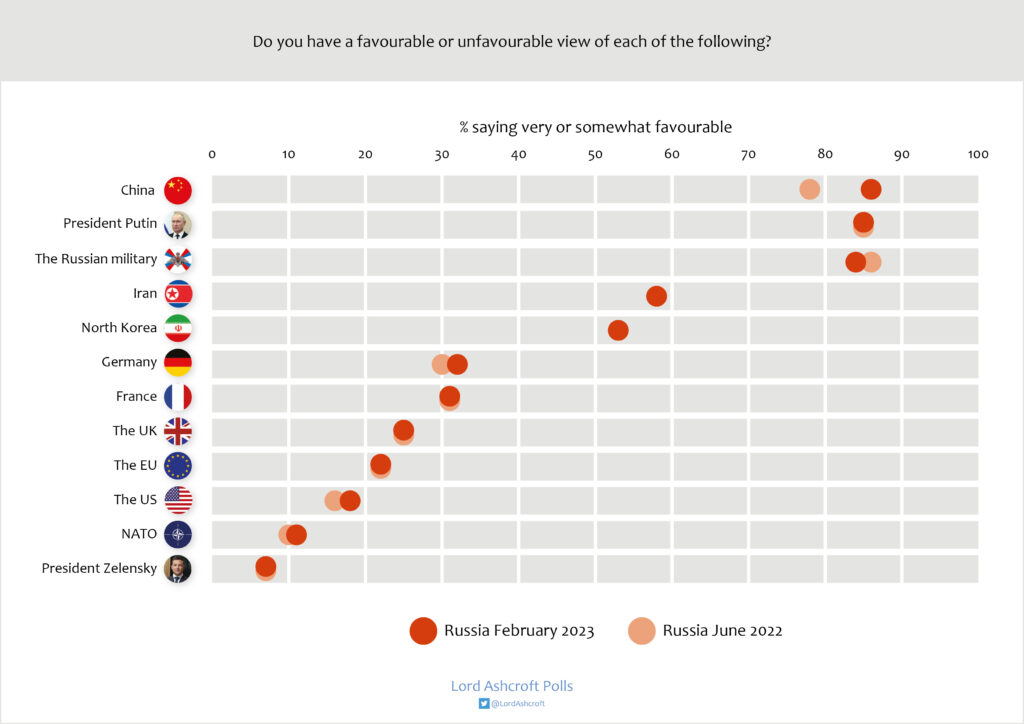

At 85%, the proportion of Russians saying they have a positive view of Putin is unchanged since last summer, his popularity rivalled only by the Russian military and China. Strikingly, Iran and North Korea enjoy more positive ratings in Russia than Germany and France, let alone the UK and America.

Our groups had plenty of complaints about life in Russia, but these were not laid at Putin’s door. rocketing prices, shoddy goods, poor services, and endemic corruption – but laid the blame elsewhere. “It is not our president, his head is busy with more important issues,” one told us. “Sometimes he appoints people, and they make mistakes, and he replaces them with other people. Though actually, the rate of mistakes is very high.”

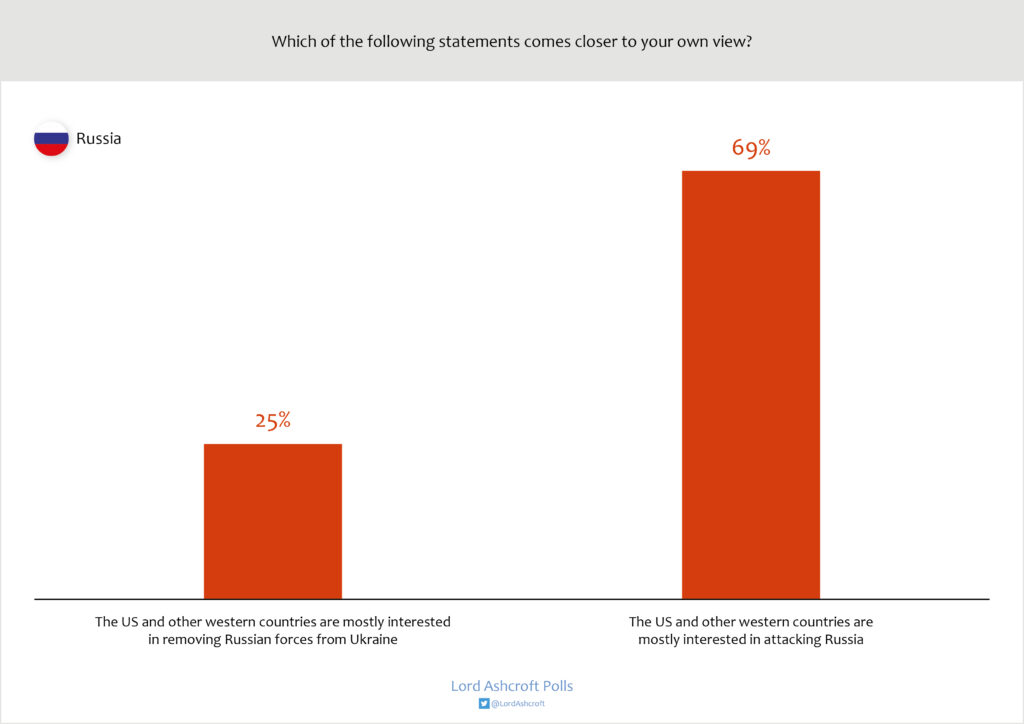

Though not everyone backs the Kremlin, and a large majority of young Russians would support negotiations to end the war, we should not imagine that most who are sceptical about military action are in any way pro-West. Few have a positive view of western countries or organisations, and a large majority think the allies are more interested in attacking Russia than in liberating Ukraine.

“The USA has always hated Russia, or envied us. For years they have tried to destroy Russia,” complained one. “NATO are the organisers of wars… All the countries that are assisting Ukraine are our adversaries in reality.”

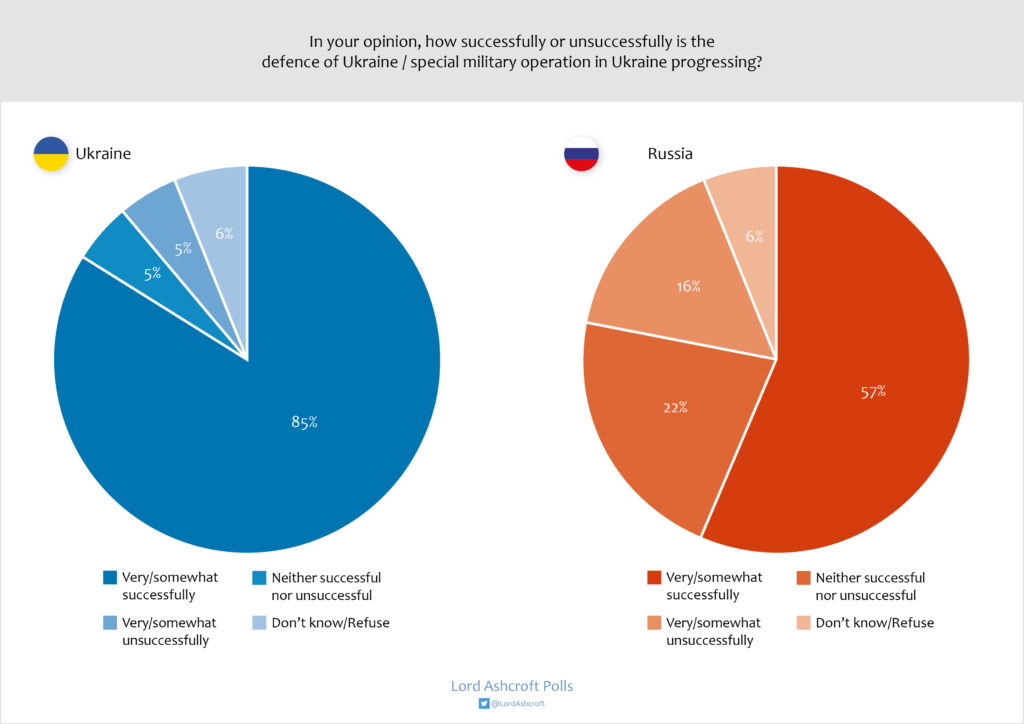

Despite their backing for the invasion and the president who ordered it, many know that “not everything is going according to the objectives,” as one Russian focus-group participant put it. While 85% of Ukrainians say the defence of their country is progressing successfully, only just over half of Russians say the same of their “operation.”

“On the battlefield the situation is terrible,” said one participant. “Relatives are buying uniforms and food. People are mobilised but they send them there without taking care of them.” Many also feel their government underestimated their adversary: “Nobody expected Ukraine to stand firm for such a long time. The analysis was a little bit wrong;” “If 300,000 people are called up and we still can’t win, the military commander is not successful.”

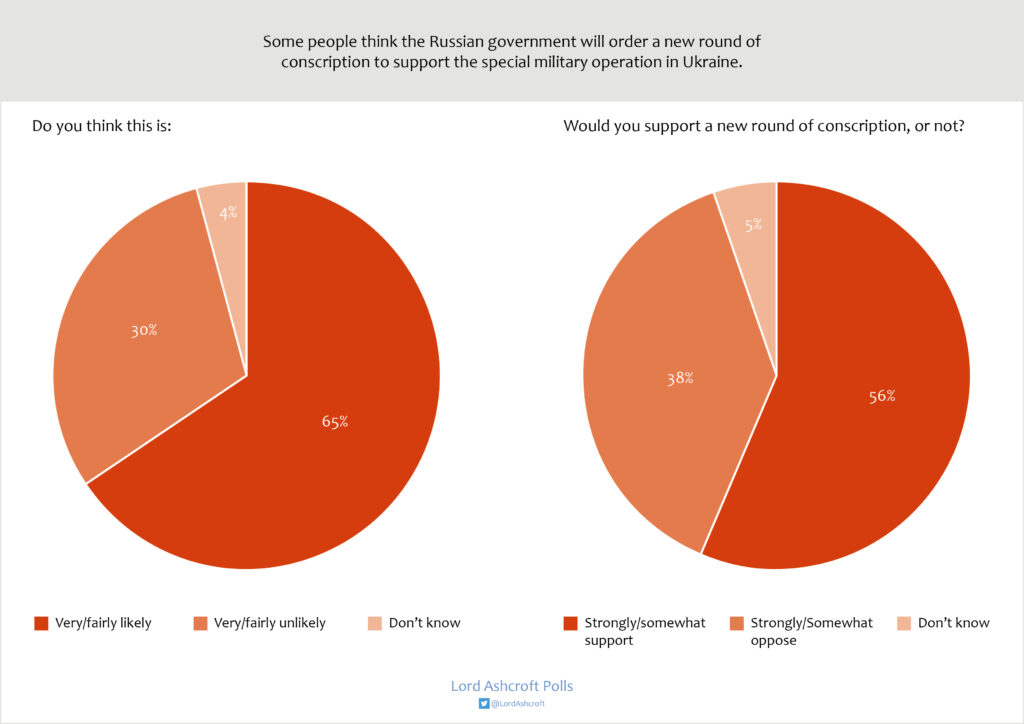

Accordingly, two thirds of Russians expect a new round of conscription to shore up the military operation. Just over half say they would back such a move – though the 18-24-year-olds who would presumably provide be sent to fight oppose the idea by two to one.

Even so, many of those who had doubts about the “operation” or thought it was going badly still thought it should be carried through. There was also widespread scorn for those who had left the country to avoid the call-up. “My husband ran away to Europe and I decided to divorce him,” declared one woman. “If he can’t defend the country, I don’t need him as a husband.”

Ukraine and (eventual) victory

One in three Ukrainians and 42% of Russians expected the war to last at least another year. Despite this, only just over 1 in 10 said they would leave the country if they could, and there was no appetite among Ukrainians to compromise with their invaders. “Victory is the 1991 borders and joining NATO, returning Crimea. That is a minimum,” said one of our Kyiv participants.

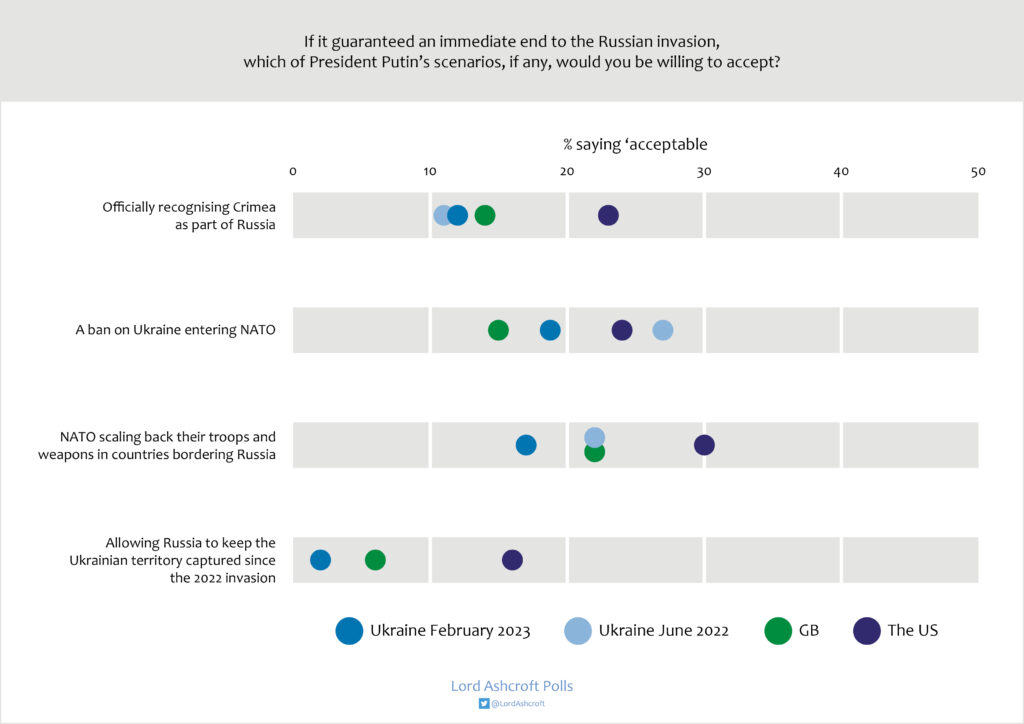

Large majorities opposed trading territory for peace, accepting a ban on NATO membership, or NATO scaling back its presence in the region. Though also opposed on balance, Americans were more willing that Ukrainian or British respondents to accept each scenario.

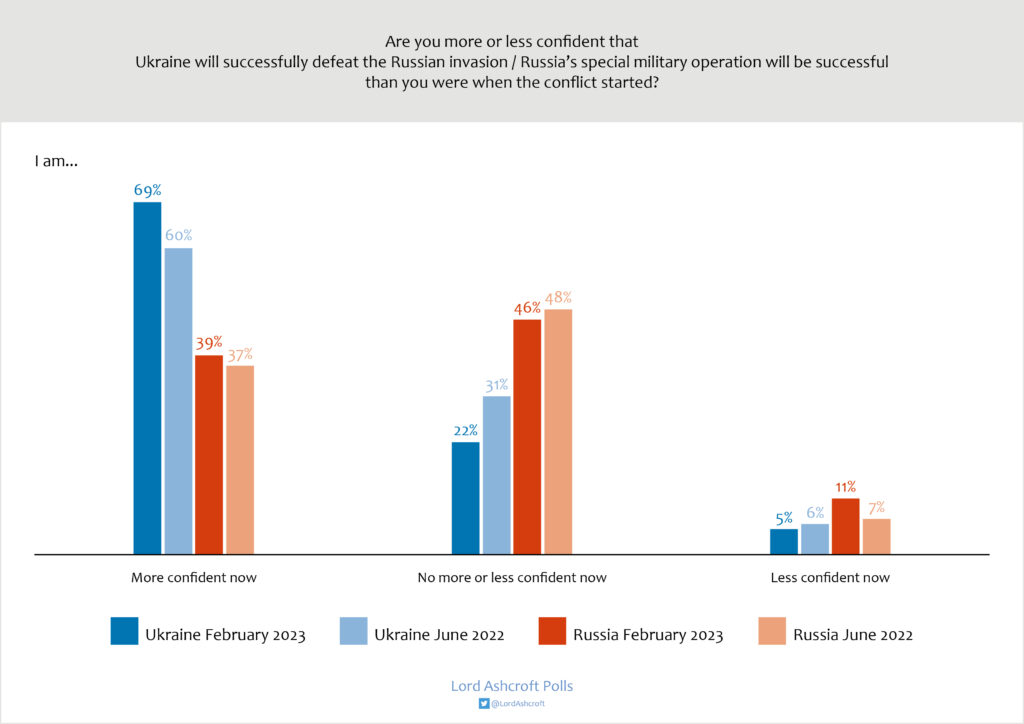

Ukrainians’ unwillingness to compromise looks closely related to their increasing optimism that they will emerge as the victors. Nearly 7 in 10 (69%) said they were more confident of defeating the invasion than they were last February, up from 60% in June. Russian respondents were notably less likely to say they were more confident – in fact 6 in 10 agreed with the statement “Ukraine seems to be resisting Russian forces more strongly than I would have expected.”

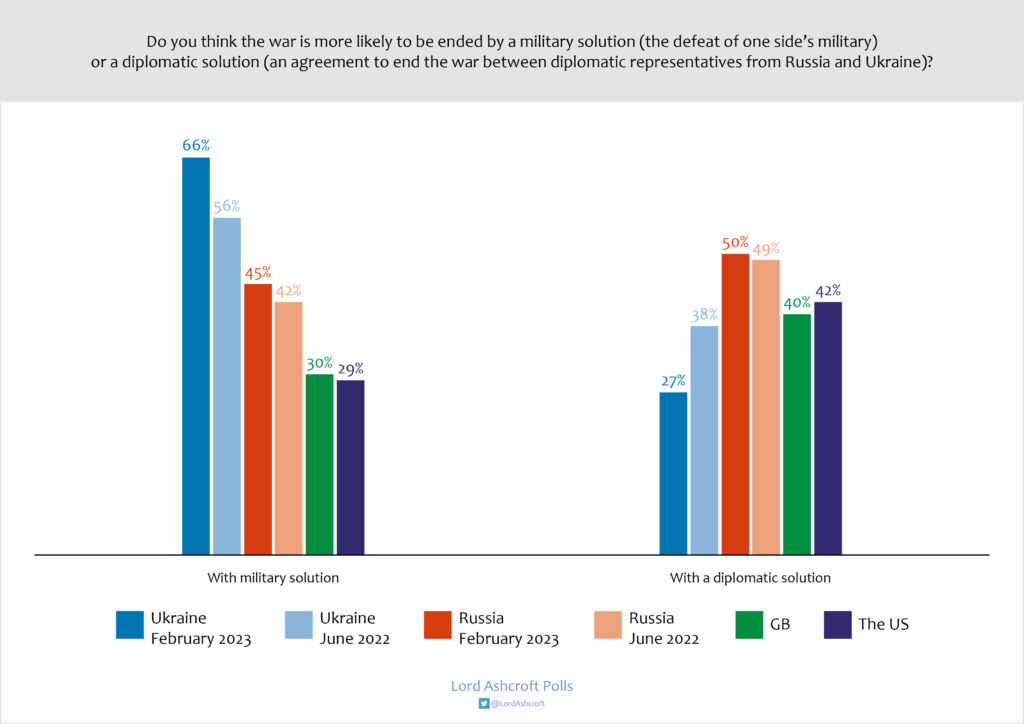

Moreover, Ukrainians are increasingly likely – and more likely than those in Britain, the US or indeed Russia – to believe the war will end in a military victory than in a diplomatic solution.

They are also more likely than before – and more likely than Russians – to think the conflict will remain between the two states rather than spread to other countries in the region or develop into a wider war.

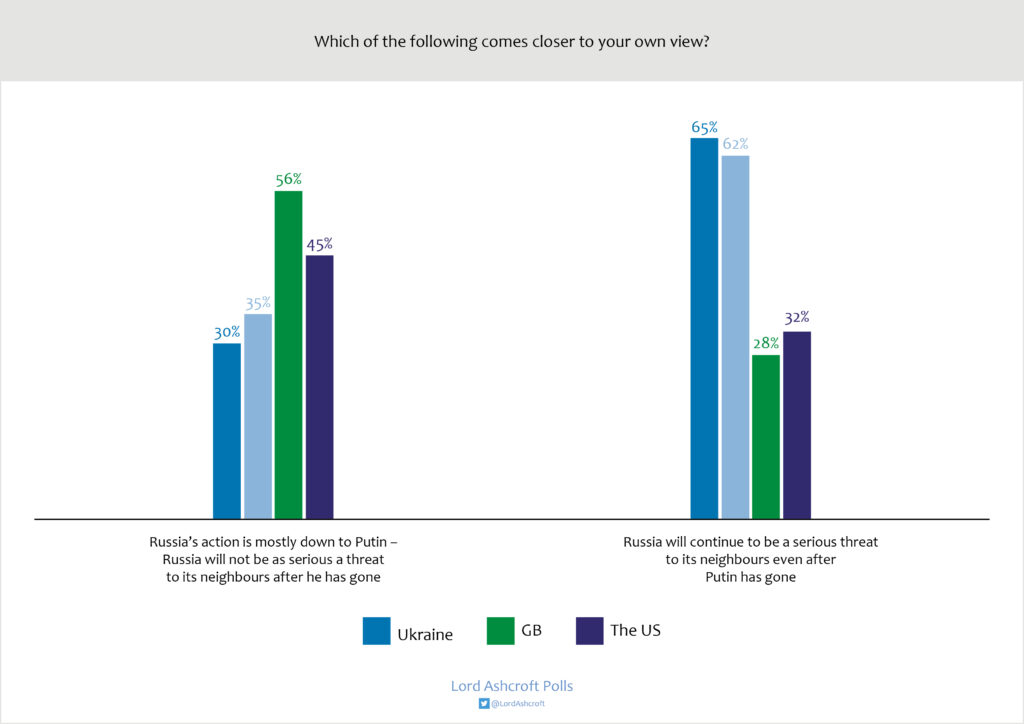

As for the future, while British and American voters tend to associate the Russian threat mainly with Putin, by a wide and growing margin Ukrainians believe Russia will continue to menace its neighbours long after the president has left office. “We need to become more like Israel,” said a woman in Kyiv. “Since 1947 they have lived in a war situation. We need to learn from them how to live in a condition of war.”