Below is the text of my presentation to the International Democrat Union Forum in Berlin: Regional Views on the War in Ukraine.

Over the last three weeks I have conducted polls in both Ukraine and Russia, along with 11 other countries in the region: Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, Serbia and Georgia.

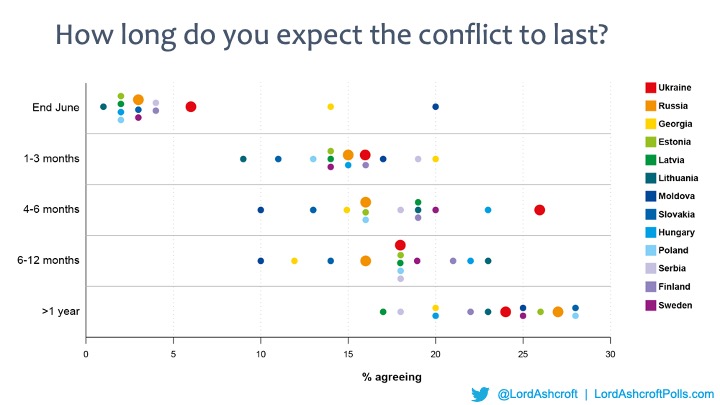

Let’s start with the conflict itself. In Ukraine, people are digging in for a long war. More than two in three Ukrainians expect the conflict to last at least another four months – more than in any other country we surveyed. A quarter expect it to be going on more than a year from now.

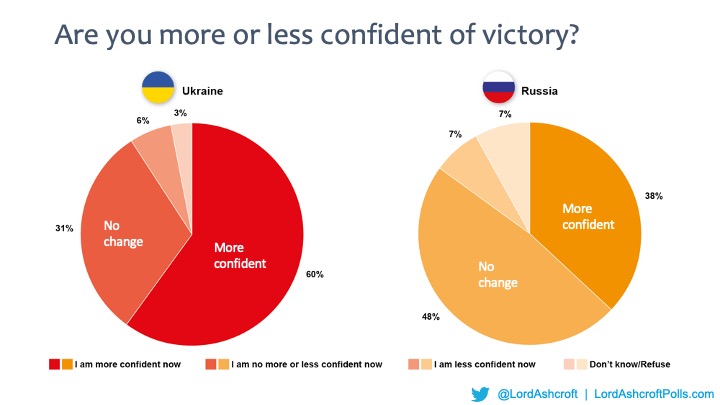

At the same time, they seem undaunted. 60% of Ukrainians told us they were more confident of defeating the Russian invasion now than they were when the conflict started. This compares with just 37% of Russians who say they are more confident that the “special military operation” will be a success than they were when it began.

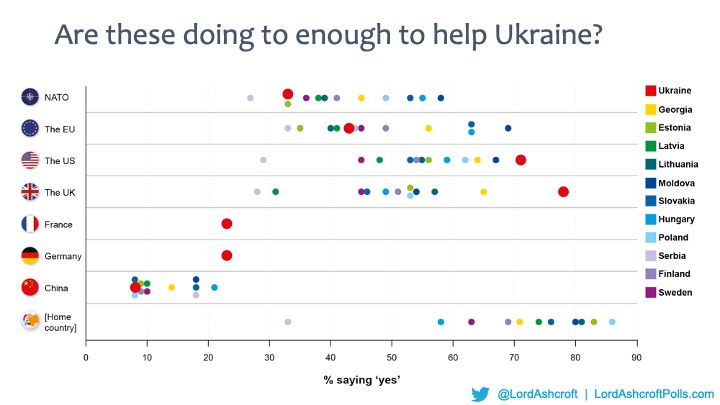

In both Ukraine and the neighbouring countries, we asked whether various states and institutions were doing enough to help. The general response was that people thought their own country was doing terribly well.

Figures were much less good for NATO. Though it’s hard to define its role given the limited appetite for military involvement, which we will come to later, fewer than half of respondents in most countries thought NATO was doing enough. Figures were slightly better for the European Union.

When we asked the same question of Ukrainians themselves, the picture was stark. Fewer than one in four thought France or Germany was doing enough, one in 3 said the same of NATO and just over 4 in 10 were satisfied with the EU. The United States was thought to be doing better, and top of the list, I’m pleased to say, was the UK. I’m told it really is true that Ukrainian soldiers shout “God save the Queen” when firing their British anti-tank weapons.

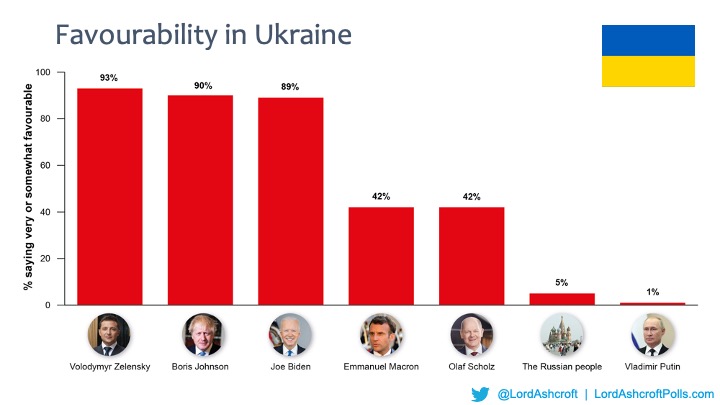

Accordingly, President Biden is more highly regarded than President Macron or Chancellor Scholz, and we have the rather extraordinary finding that Boris Johnson is nearly as popular as President Zelensky himself. Which leads to the idle thought that if Boris is to face another confidence vote, he should ask that it be held in Kyiv rather than Westminster.

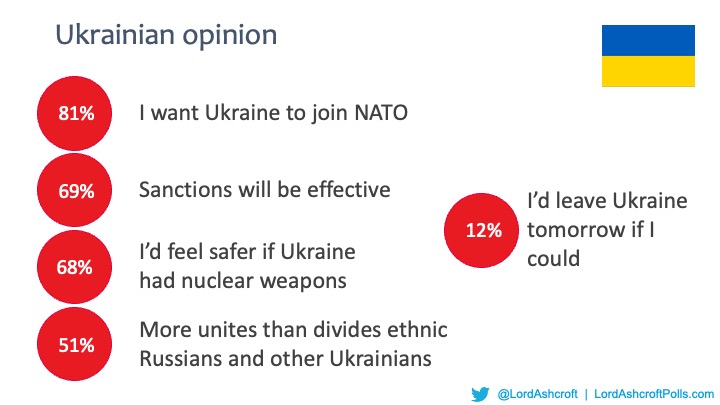

We asked Ukrainians in more detail about their perspective. More than two thirds said they would feel safer if they knew their country had nuclear weapons, and more than 8 in 10 said they would like Ukraine to join NATO. A sign of their determination is that only 12% said they would leave the country tomorrow if they could. Remarkably, more than half said there was more that united ethnic Russians with other Ukrainians than divided them – though this was down from two thirds compared to my earlier survey three months ago.

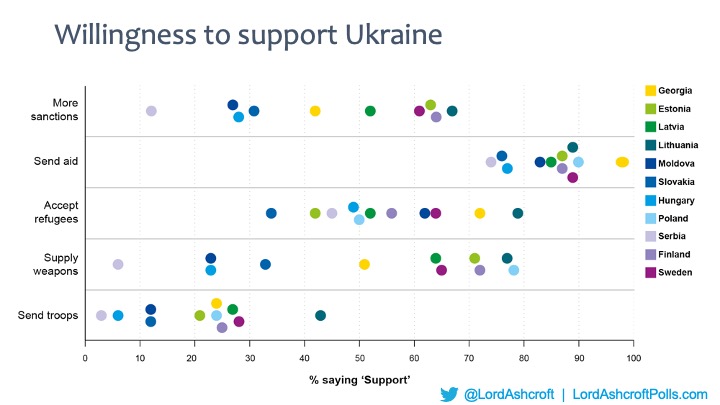

In the neighbouring states, we asked how willing or otherwise people would be to help in various ways. Few objected to the idea of sending aid, such as medical supplies, but other measures were more controversial. In Lithuania, Estonia, Poland and Finland, around two thirds were prepared to impose further economic sanctions on Russia even if this had an impact in their own country. This compared to around 3 in 10 in Moldova, Slovakia and Hungary, and only 12% in Serbia. 79% of Lithuanians would be prepared to accept large numbers of Ukrainian refugees, compared to 34% of Slovakians. And while more than three quarters of Lithuanians and Poles were willing to provide weapons and ammunition to Ukrainian forces, only 23% of Hungarians and Moldovans, and 6% of Serbs said the same. Support for direct military intervention was lower across the board, though Lithuanians were once again the most willing: 43% of them said they would be prepared to send troops to fight alongside Ukrainian forces.

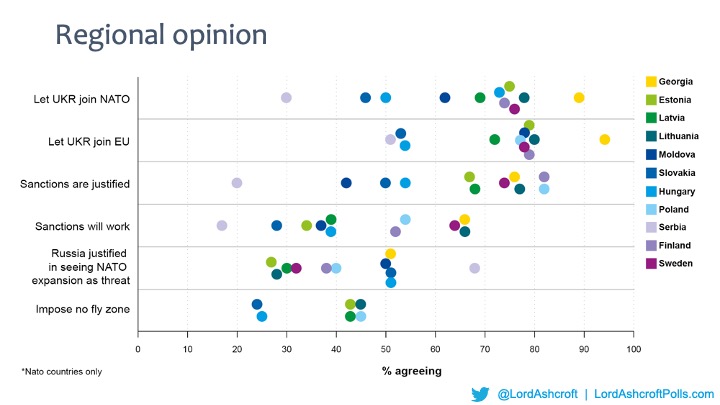

We saw a similar divergence of opinion on other issues. Clear majorities in most countries thought Ukraine should be allowed to join NATO if it so wished – the exceptions being Slovakia, Hungary and Serbia. Most populations thought sanctions against Russia were justified – though people in Moldova, Slovakia and Hungary were ambivalent, and most Serbs were opposed.

Perhaps surprisingly, a fair proportion of respondents – and a majority in some countries – agreed that Russia would be justified in seeing the expansion of NATO as a threat to its security.

In the NATO countries we surveyed, we also asked whether a no-fly zone should be imposed over Ukraine, even if that meant forces from their home country shooting down Russian military aircraft. In Poland and the Baltic states, not far off half of respondents said they approved of the idea – though again support was much lower in Slovakia and Hungary.

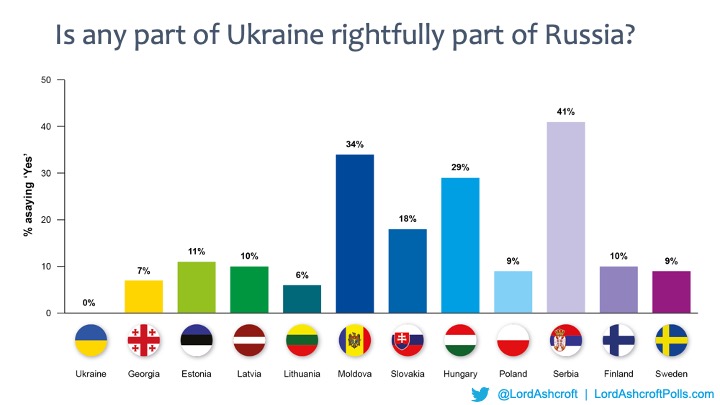

In most countries, overwhelming majorities said they thought no part of Ukraine was rightfully part of Russia, but again there were exceptions. Nearly one fifth of Slovaks, 3 in 10 Hungarians, one third of Moldovans and 41% of Serbs think Russia has a legitimate claim to Ukrainian territory.

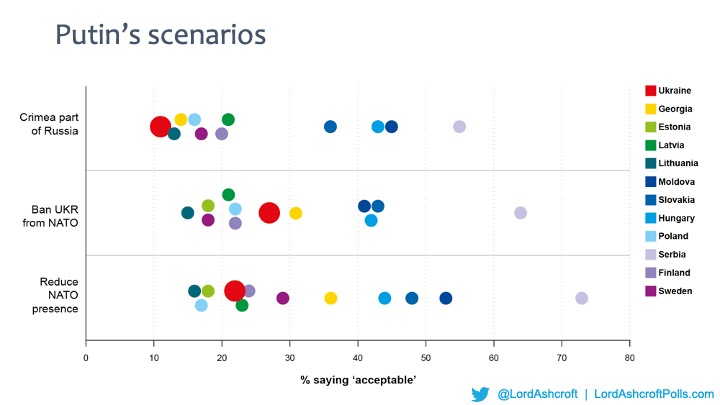

By the same token, there was scant support for any of Putin’s scenarios for ending the conflict. Poland and the Baltics were particularly opposed both to official recognition of Crimea as part of Russia, and to NATO scaling back its troops and weapons in countries bordering Russia. There was little support for a ban on Ukraine joining NATO. But in Serbia, a majority found all three proposals acceptable, and there was substantial support for these compromises in Moldova, Slovakia and Hungary.

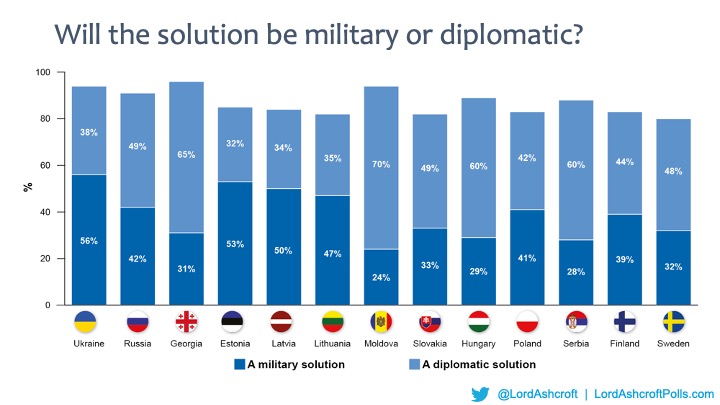

Evidently feeling that they have no option but to fight, Ukrainians were the most likely to believe that the conflict would only be ended by the military defeat of one side by the other. The Baltic states were the only other places to think a military solution was the more likely outcome. Everywhere else, including Russia, people were more likely to think the war would end through diplomacy.

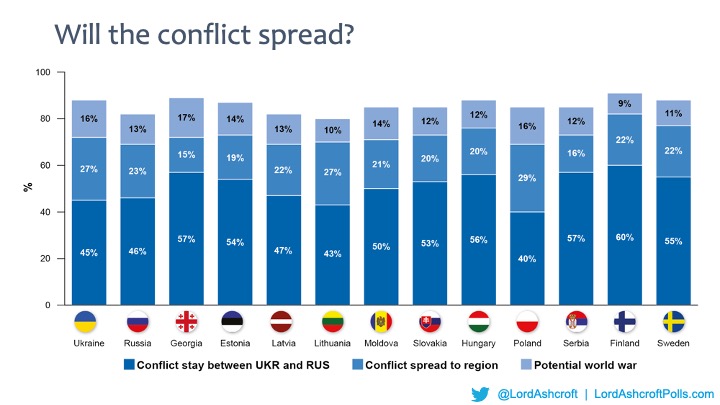

Another striking finding was that barely half of respondents across the board believed the military conflict would remain between Ukraine and Russia. Around one third – and nearly half of Ukrainians and Poles – thought it would either spread to other countries in the region or develop into another world war.

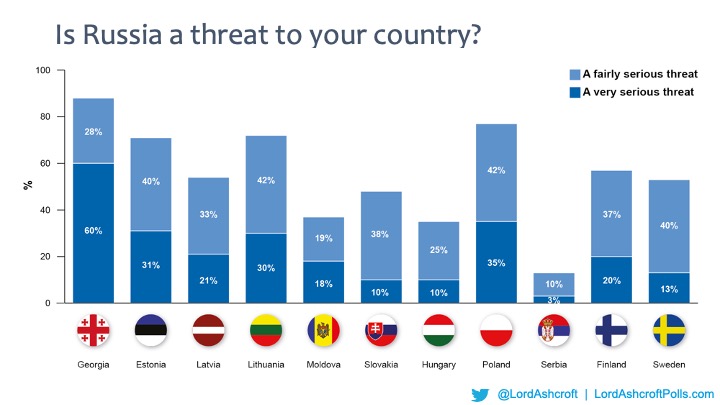

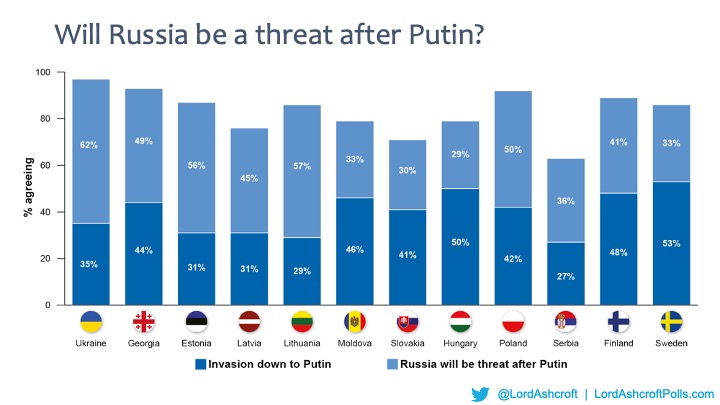

Not at all surprisingly, some populations in the region saw Russia as a serious threat to their own country. This was especially true in Georgia, Estonia, Lithuania and Poland. People in Moldova, Hungary and Slovakia were less convinced, while a majority of Serbs said Russia was not a threat at all.

Equally notable was that while our Scandinavians and respondents in Moldova, Slovakia and Hungary tended to think that any threat was mostly down to Putin, those in Poland, the Baltics, Georgia and – especially – Ukraine were more likely to believe that Russia would continue to be a danger to its neighbours even after Putin had left the scene.

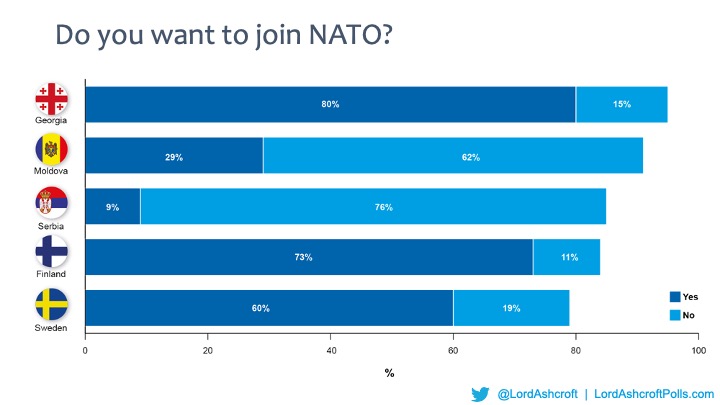

That being the case, clear majorities in Georgia, Finland and Sweden said they would like to see their countries join NATO – though the answer from Moldova and Serbia was a resounding “no thank you”.

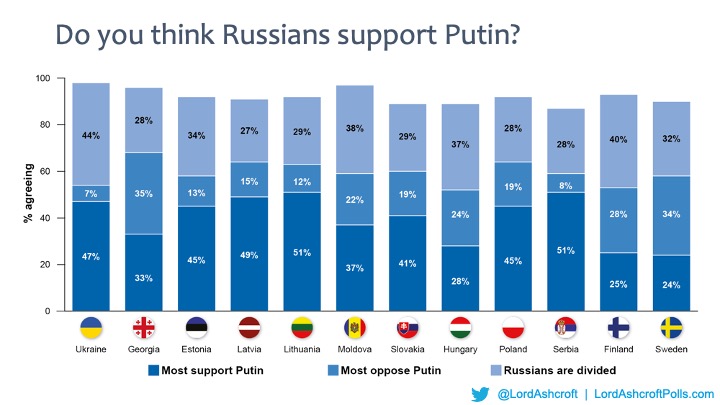

We also looked in more detail at opinion within Russia itself. Externally, we found people believing that most Russians support Putin, or are at least evenly divided. In the countries we surveyed, few believed that a majority of Russians opposed the Putin regime.

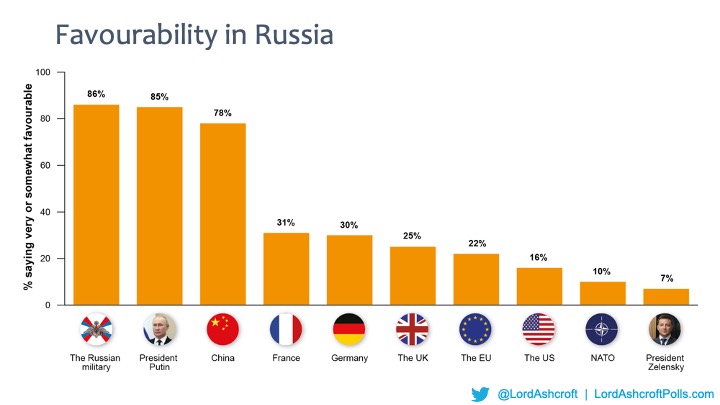

From our own evidence, they’re right about that. We found 85% of Russians saying they had a favourable view of the president, a result unchanged from my survey in March. (In other words, Putin is nearly as popular in Russia as Boris is in Ukraine). The very positive view of China is also worth noting.

Polling in Russia comes with the obvious caveats that the regime effectively controls what Russians see and hear on the news, and that people might be cautious in talking about their views to a stranger. Nevertheless, the research from other sources is fairly consistent, and shows little change since before the clampdown that followed the invasion.

It is also instructive to note the different responses from different groups. For example, those aged under 25 – while almost as favourable towards Putin – were more than twice as likely as Russians as a whole to have a positive view of NATO, the EU, and the western countries we asked about.

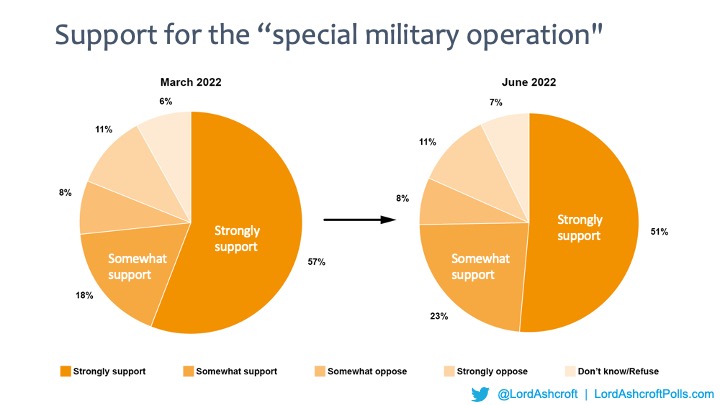

We found three quarters of Russians saying they supported the “special military operation” in Ukraine – a figure unchanged overall since my survey in March, except that there had been a slight shift from strongly supporting to only somewhat supporting the invasion. Again, notably, fewer than half of 18 to 24-year-olds said they supported the invasion, compared to 84% of those aged over 55.

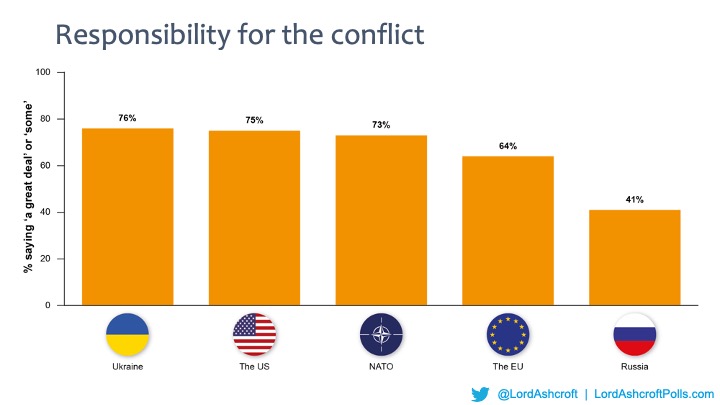

Asked who they thought was to blame for the current conflict, Russians were most likely to name Ukraine, followed closely by the US and NATO. Only a minority said they thought Russia itself had any responsibility.

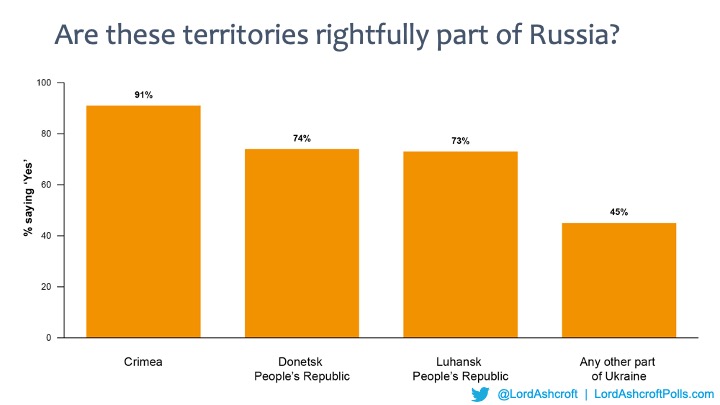

91% told us they thought Crimea was rightfully part of Russia, a figure unchanged since March. Three quarters of Russians said they felt Donetsk and Luhansk were also part of their country – both of these figures have edged up by a few points since we asked the question three months ago.

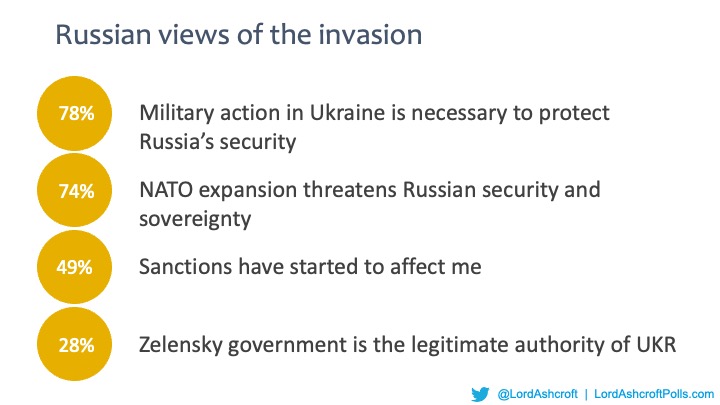

Further questions showed how far Russians support the Putin narrative. More than three quarters agreed that military action in Ukraine was necessary to protect the security of Russia, and that the expansion of NATO is a threat to Russia’s security and sovereignty. Fewer than 3 in 10 see President Zelensky’s government as the legitimate authority of Ukraine.

While those under 25 were as likely as others to see NATO expansion as a threat, only just over half agreed that military action in Ukraine was necessary to protect Russia’s security.

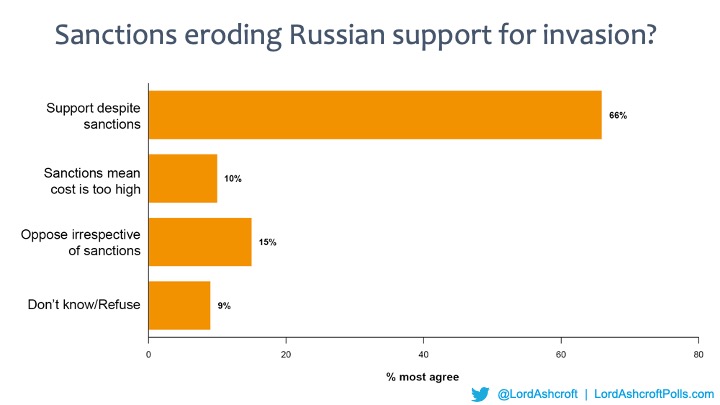

Support for the invasion remains strong even though half of Russians told us economic sanctions had started to affect them or people they know.

In fact, when we asked the question a different way, we found two thirds of Russians saying they supported the invasion despite the sanctions, and 15% saying they would oppose it whether there were sanctions or not. Only 1 in 10 said they would support the special military operation, but the sanctions meant the cost was too high and the action should end.

Looking at their wider view, we find 86% saying they trust Russia’s current leadership to make the right decisions for the country, and 79% saying they believe Putin has the best interests of ordinary Russians at heart. While 4 in 10 say they think Russia’s international reputation has been damaged in recent years, that figure has actually fallen by 5 points since the invasion. More than 8 in 10 say they think Russia will emerge from the current conflict stronger than it was before – though more than half also admit that Ukraine seems to be resisting Russian forces more strongly than they would have expected. Once again, if you have the chance to study the detailed figures later, you will see that the youngest Russians took a more sceptical view of the Kremlin line than their older counterparts.

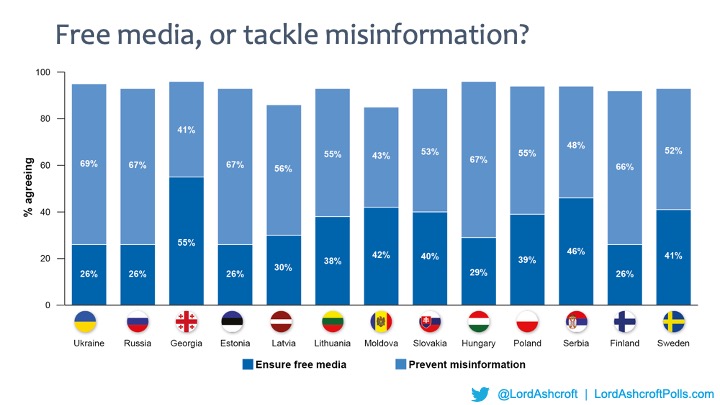

Finally, a finding which I must admit took me slightly by surprise. We asked which was more important – ensuring the media are free to report without restrictions, or ensuring people are not exposed to misinformation. I expected the Russians to choose the second option and endorse Putin’s control of the media. When we found an identical result in Ukraine, I reasoned that they would want to prevent the spread of enemy propaganda in wartime. What I did not expect was to find the pattern repeated throughout the region. In fact, of all the countries we surveyed, Georgia was the only one where people said media freedom was the more important priority. We can debate what this means and what the implications are, but I certainly found that a striking result in the current climate.

Overall, then we see that opinion in the region is far from monolithic – with variations probably explained by each country’s historic ties and loyalties, demographics, and current political and commercial realities. We see Russians still largely in support of their leader and his policies. And we see Ukrainians determined and optimistic, digging in for a long war, and with a clear view of who is helping and who isn’t – together with a widespread expectation that the conflict could spread beyond its current borders.