The Irish border is at the centre of negotiations as to how we will leave the European Union. My latest research, published today, explores what people think about the issue on both sides of the border, how voters in Great Britain see the question in the context of the wider Brexit debate, and the potential implications for the union of nations in the United Kingdom. My report is called Brexit, The Border And The Union, so let’s take those themes in turn.

Brexit

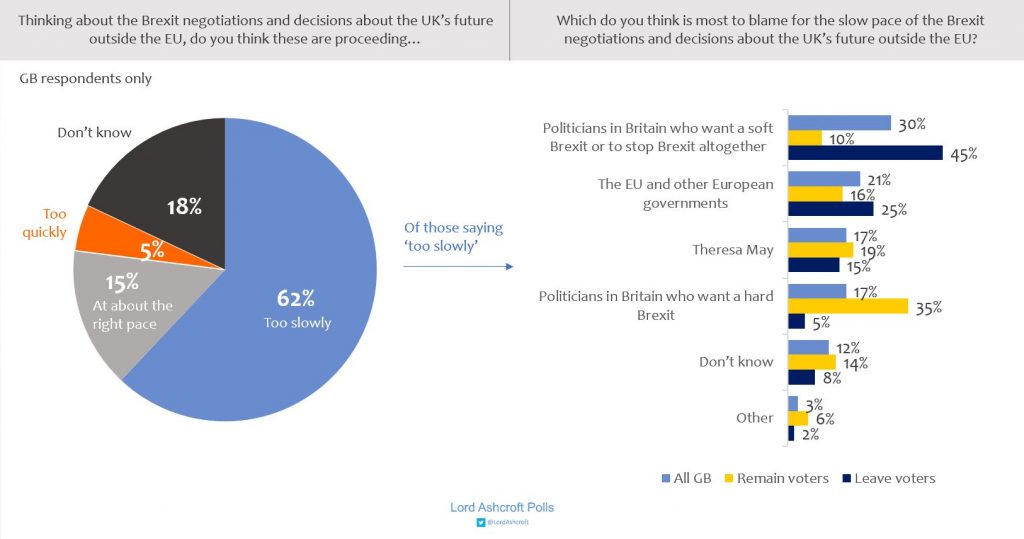

Three quarters of Leave voters in Britain – and a majority of remainers – said they thought the Brexit negotiations and decisions about the UK’s future outside the EU were proceeding too slowly. Nearly half of leavers thought the responsibility lay with British politicians who wanted a soft Brexit, or to stop it altogether, with a quarter blaming the EU and other European governments. Remainers spread the blame more widely, but were most inclined to point the finger at those pushing for a hard Brexit.

In our focus groups, most Conservative Leave voters had some sympathy for Theresa May: “there’s probably a lot to put into place. It wasn’t ever going to happen overnight; “she’s doing the best she can. She’s picked on by the men;” “Brussels are making it as difficult as they possibly can. As long as we’re still there, they’re still getting money out of us.” But some thought the government should be tougher in its approach: “I’m concerned we will end up with a watered-down version. I don’t think we have a strong enough negotiating team… There’s a lot of appeasement going on.” Many non-Tory leavers held the party responsible: “I blame the Tories, Theresa May. They didn’t expect us to leave. They haven’t got a clue what to do;” “a lot of the hold-up is because of the Conservative leadership battle.”

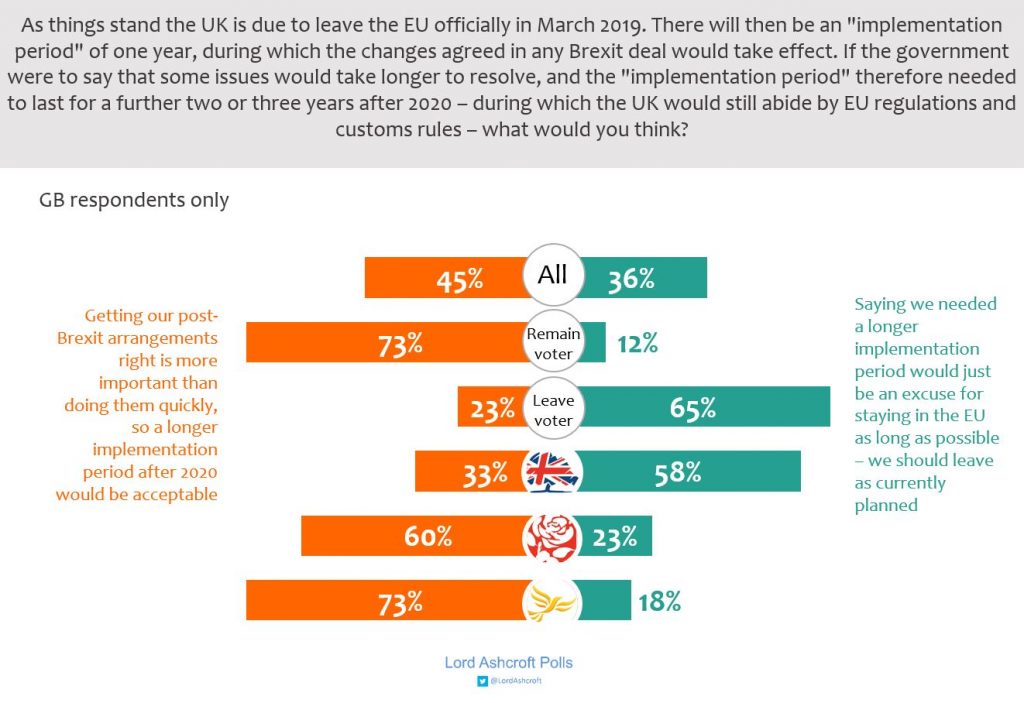

We also asked people, hypothetically, how they would react if the government were to say we needed an extension to the planned ‘implementation period’ in order to resolve complex issues. Overall, voters were more likely than not to say this would be acceptable, and three quarters of remainers agreed that “getting our post-Brexit arrangements right is more important than doing them quickly.” But two thirds of Leave voters, and a majority of Conservatives, thought a longer implementation period “would just be an excuse for staying in the EU as long as possible,” and that we should leave as currently planned.

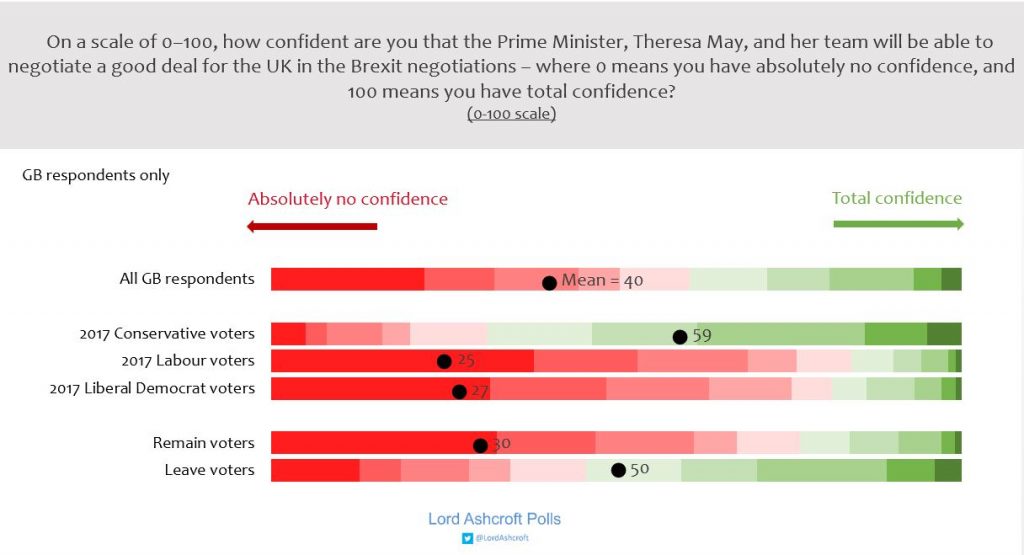

Asked how confident they were that Theresa May and her team would be able to negotiate a good deal for the UK in the Brexit negotiations, where zero meant they had no confidence at all and 100 meant they had total confidence, respondents in Great Britain gave a mean score of 40 (down from 42 when I last asked in November 2017). Leave voters gave a score of 50 (down from 54), and Remain voters a score of 30 (unchanged). Conservative voters’ confidence had fallen slightly from 62 to 59.

In the Republic of Ireland, more than seven in ten voters said they were unhappy that the UK was leaving the EU. Three quarters thought the country had made the wrong decision, even according to its own interests. More than half thought Brexit would make the relationship between Ireland and Northern Ireland more distant, and two thirds thought the same was true of Ireland’s relationship with the UK as a whole. Three quarters said they felt positive about Ireland’s EU membership, and 80% said they would vote to remain if there were a referendum.

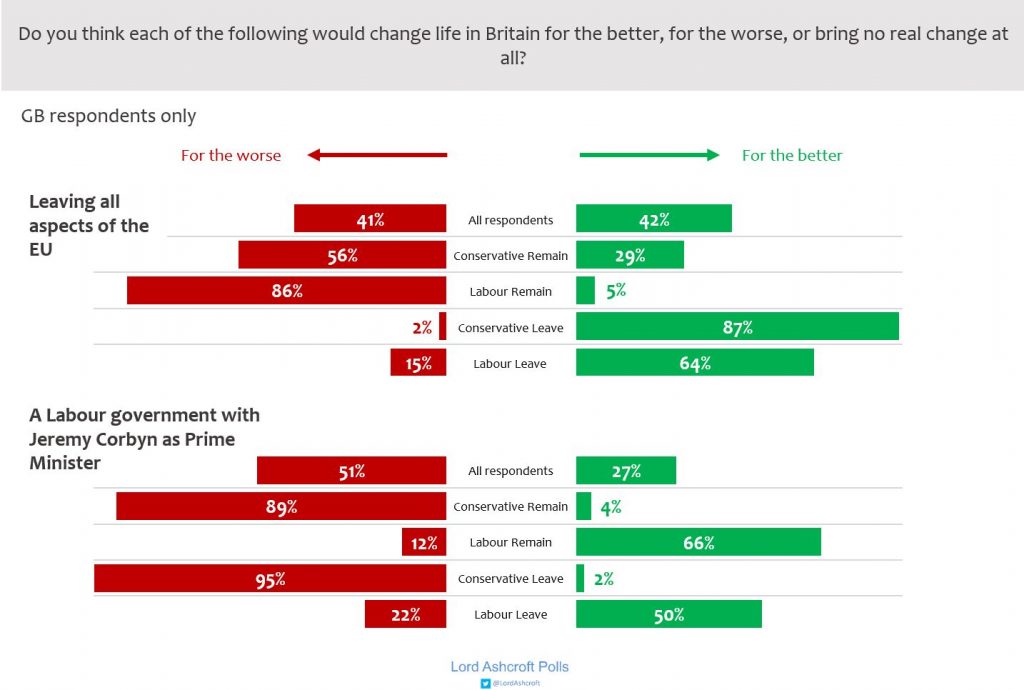

We asked voters in Great Britain whether they thought two things would change life for the better or the worse: leaving all aspects of the EU, and a Labour government with Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister. Conservative remainers were more likely to see a Corbyn government as a change for the worse than leaving the EU, while Labour Leave voters were more likely to see Brexit as a change for the better than a Corbyn government. More than one in five Labour Leave voters said they thought a Labour government under Jeremy Corbyn would be a change for the worse.

The Border

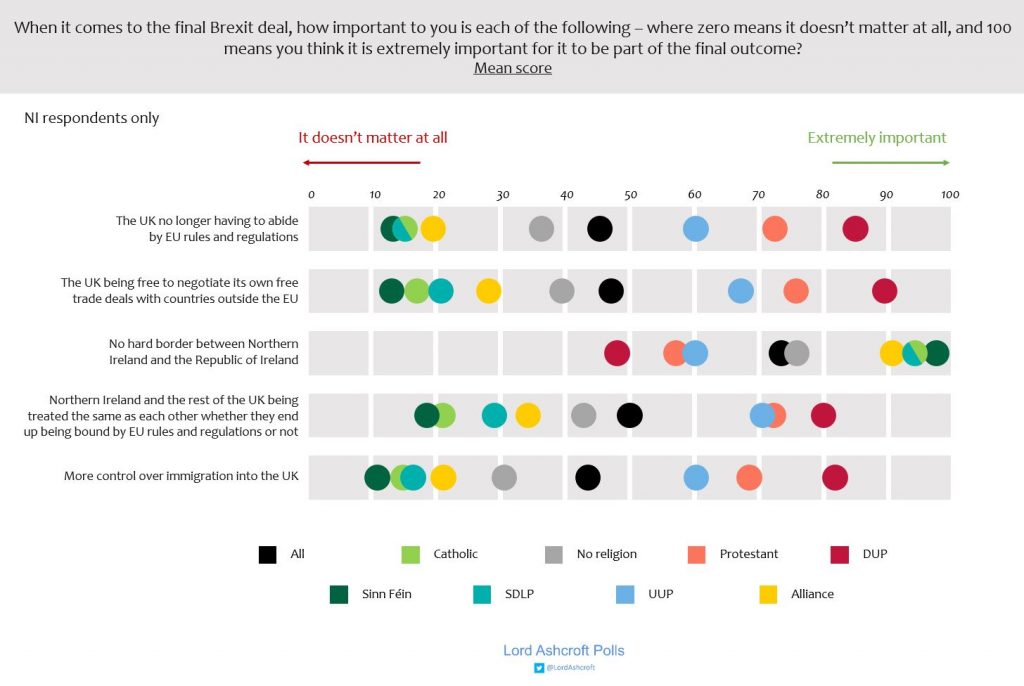

We asked people in Northern Ireland how much importance they gave to five potential Brexit outcomes. For Catholic and Nationalists voters, avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic was far and away the most important consideration. For Unionists and Protestants, however, the issue mattered much less than ensuring the UK was able to negotiate its own free trade deals with non-EU countries, was no longer bound by EU rules, and had more control over immigration into the UK. Making sure Northern Ireland was treated the same as the rest of the UK was also more important than preventing a hard border.

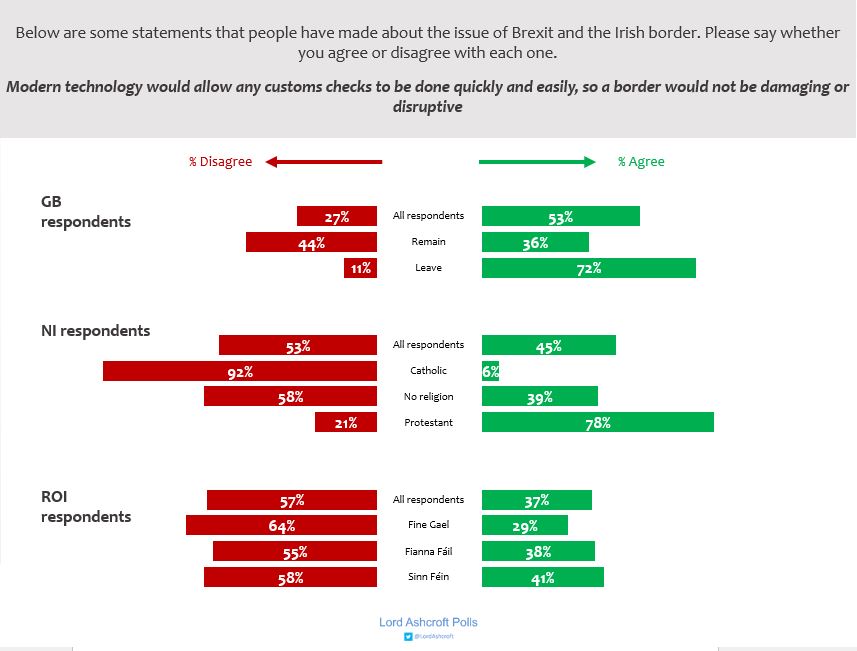

Most Leave voters in both Great Britain and Northern Ireland agreed that “modern technology would allow any customs checks to be done quickly and easily, so a border would not be damaging or disruptive.” Only just over a third of Remain voters in Great Britain agreed, along with fewer than four in ten voters in the Republic of Ireland and only 6% of Nationalists in Northern Ireland. For them, the border had wider significance: more than nine out of ten agreed that “whether or not it is practical, a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland would be a very negative symbol,” as did a similar proportion of respondents in Ireland.

In Northern Ireland, nearly two thirds agreed that a hard border “would be likely to create division and provoke paramilitary activity, threatening peace and security.” This included nine out of ten Nationalists, but fewer than four in ten Unionists – and only three in ten Leave voters and a quarter of DUP supporters.

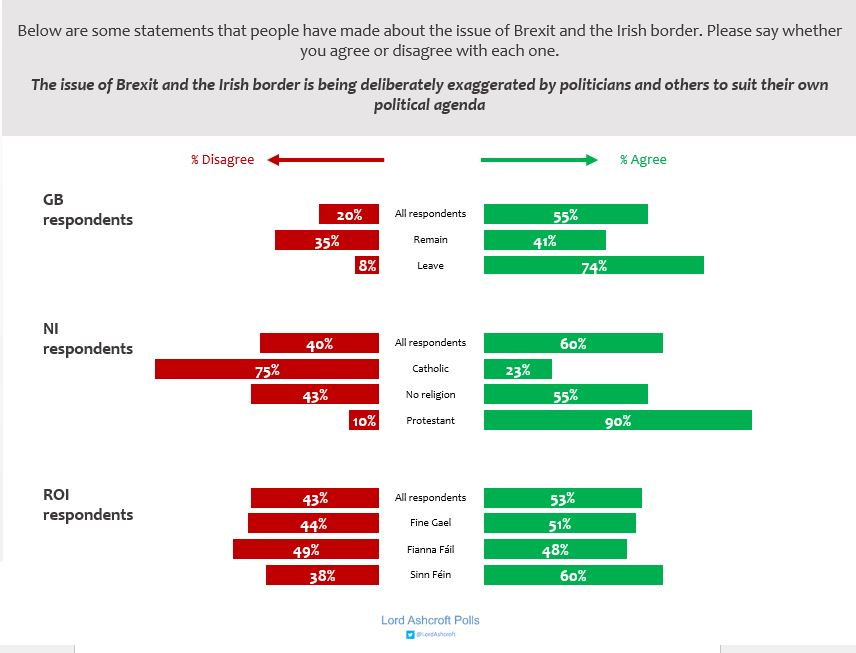

Unionists in Northern Ireland overwhelmingly agreed that “the issue of Brexit and the Irish border is being deliberately exaggerated by politicians and others to suit their own political agenda”. More than a fifth of Nationalists agreed, as did a majority in Great Britain – including three quarters of Leave voters and four in ten remainers.

In both Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the most popular solution to the issue was for the whole UK to leave the customs union even if this meant customs checks at the Irish border. In England, Scotland and Wales, the second most chosen option among Leave voters – though much less popular – was for Northern Ireland to stay in the customs union while the rest of the UK left. This was not the case in Northern Ireland, where Leave voters and Unionists said they would rather see the whole UK remain in the customs union than Northern Ireland remaining on its own.

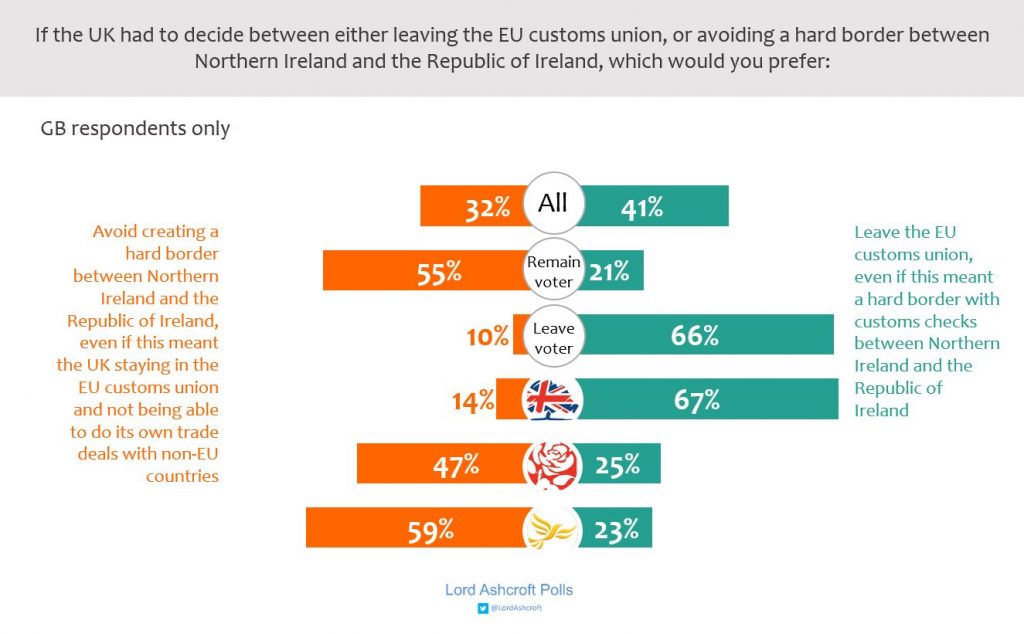

When we asked voters in Great Britain what they would prefer if it came to a choice between either leaving the EU customs union or avoiding a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, two thirds of Conservatives and Leave voters, and even one in five remainers, said they would rather leave the customs union.

The Union

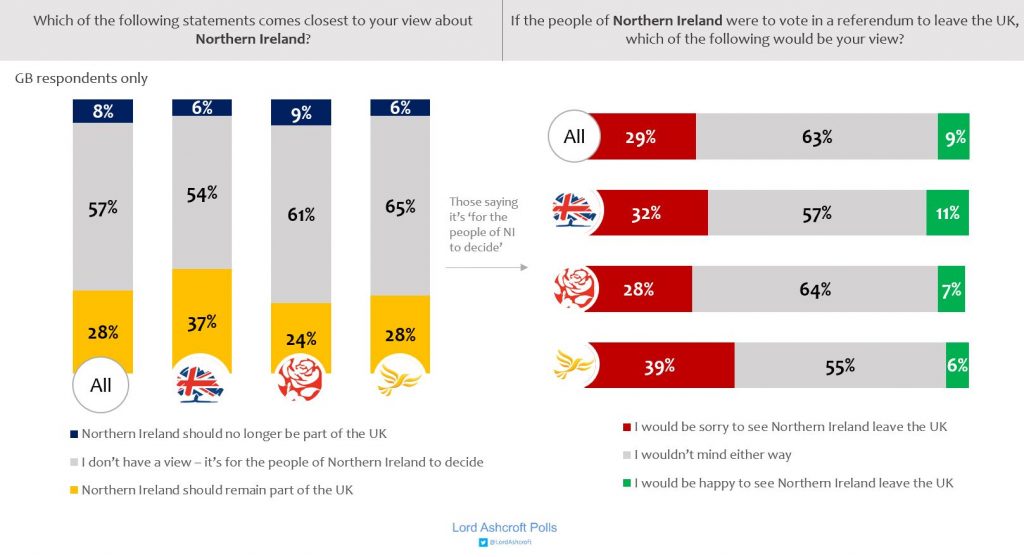

Asked whether or not Northern Ireland should remain part of the UK, a majority of voters in England, Scotland and Wales – including a majority of Conservatives – answered that it was for the people of Northern Ireland to decide. In the event that Northern Ireland did vote to leave, more of this group said they would be sorry than happy, but more than six in ten said they “wouldn’t mind either way.”

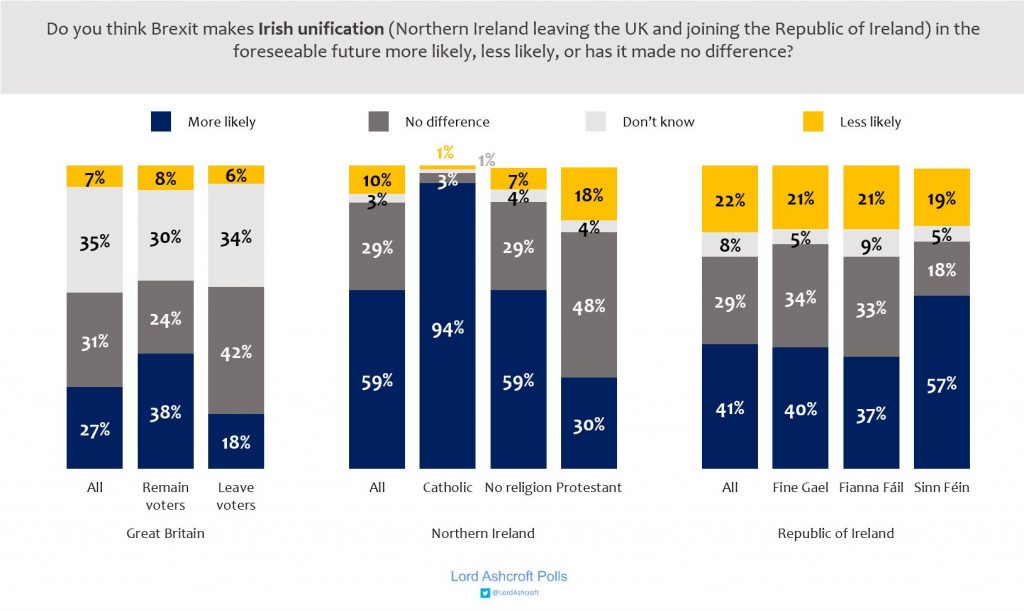

A majority of voters in Northern Ireland said they thought Brexit had made Irish unification in the foreseeable future more likely. While Catholics thought this overwhelmingly, nearly half of Protestants and a majority of DUP voters said Brexit would make no difference – though more of the remainder thought it would make unification more likely rather than less.

In Great Britain, people were more likely to say they thought Brexit had made Scottish independence more likely to think the same of Irish unification (and just over half of Remain voters thought the chances of Scottish independence in the foreseeable future had risen) – though they were also more likely to say they didn’t know in the Irish case.

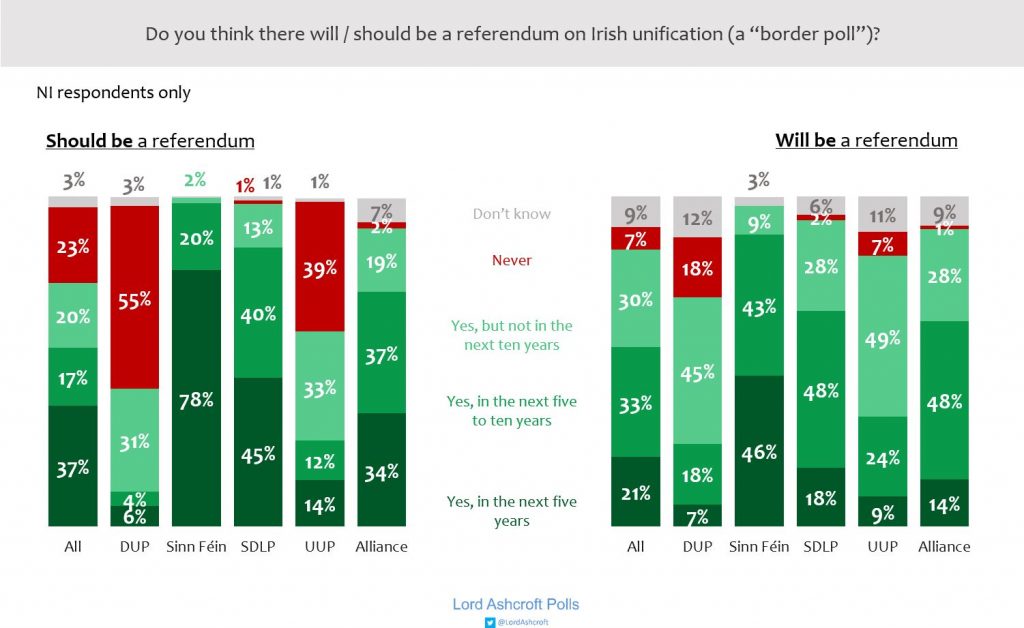

More than nine out of ten Northern Ireland Catholics thought there should be a referendum on Irish unification, or ‘border poll’, in the next ten years, and more than eight in ten thought this would actually happen. Meanwhile, 43% of Protestants (and a majority of DUP voters) said there should never be a border poll, but only 13% thought there never would be.

Strikingly, 12% of Protestants said they thought there should be a border poll within the next five years. Part of the reason may be the longer term pessimism felt by some of the DUP supporters we spoke to in our focus groups: “The sooner we have a border poll the better, because if it’s soon there is more chance of the Unionists winning it.”

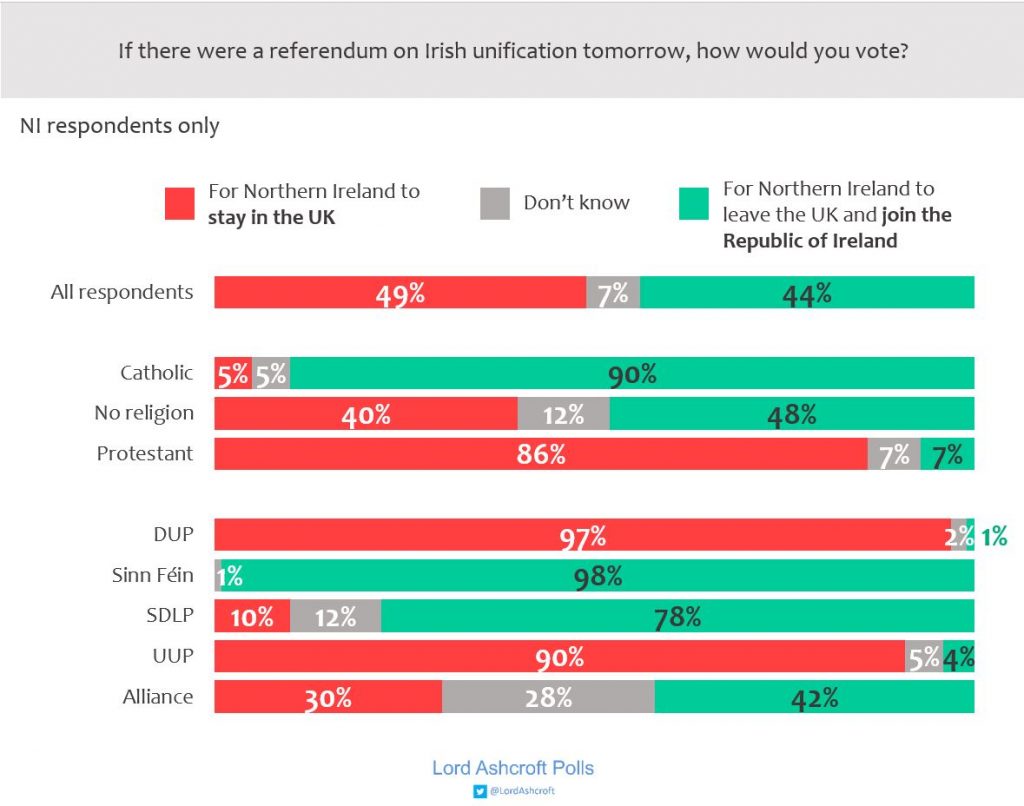

When we asked how people in Northern Ireland would vote if there were a referendum tomorrow, the margin for remaining in the UK was just five points, with 7% saying they didn’t know how they would vote. Nearly eight in ten SDLP voters said they would vote for unification, and nearly three in ten Alliance voters were undecided.

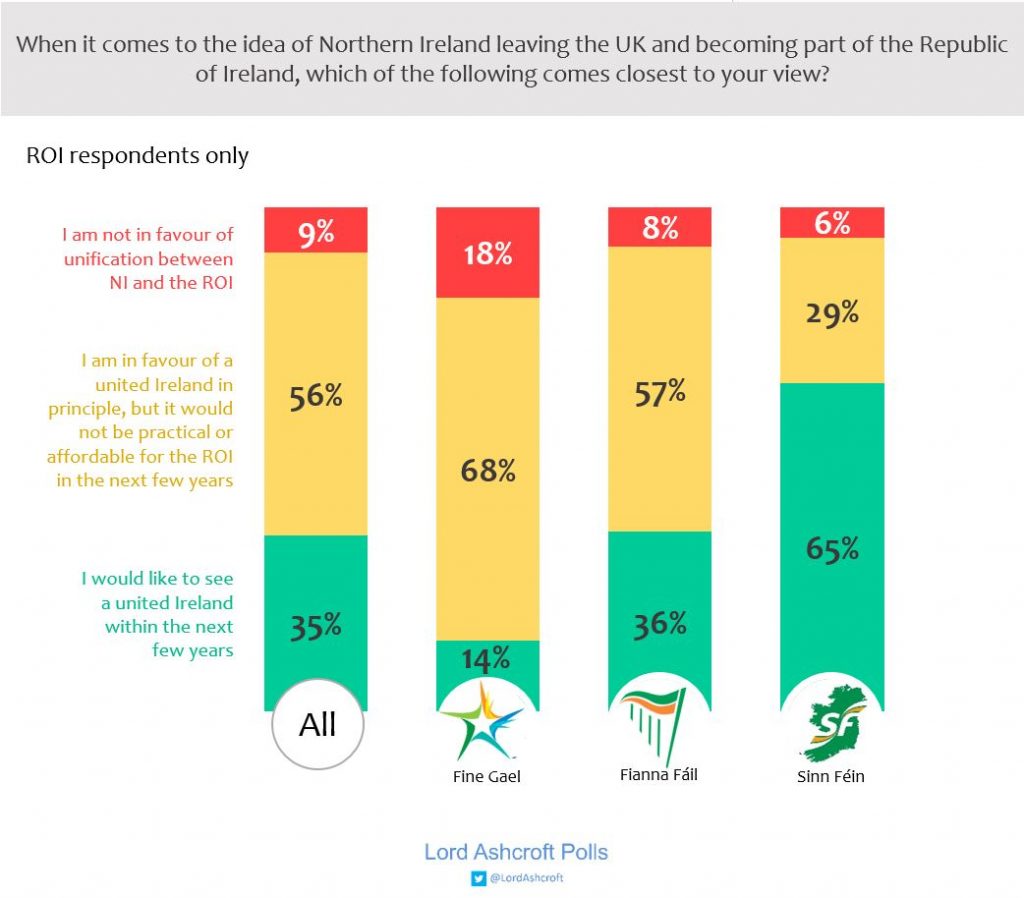

In the Republic of Ireland, however, enthusiasm for unification was limited. While just over a third said they would like to see it happen soon, more than half said they were “in favour of a united Ireland in principle, but it would not be practical or affordable for the Republic of Ireland in the next few years.”

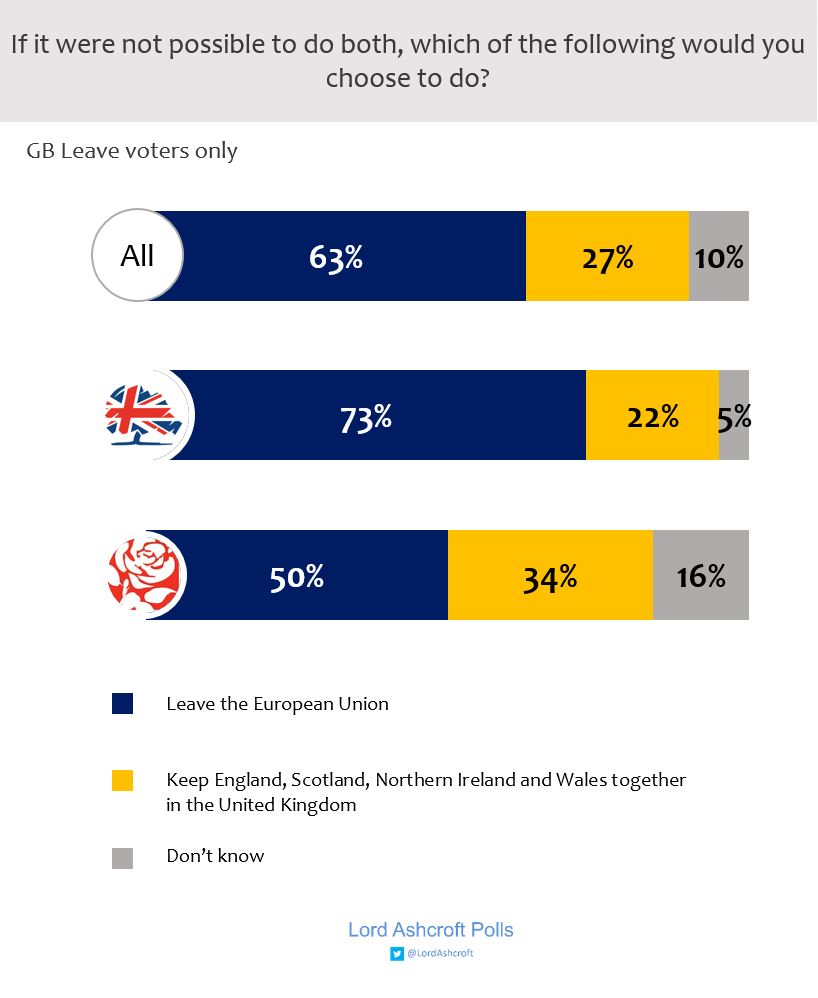

Finally, we asked Leave voters in Great Britain what they choose to do if it were not possible both to leave the EU and keep England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales together in the United Kingdom. More than six in ten, including half of Labour voters and nearly three quarters of Conservatives, said they would choose to leave the EU.